Vietnamese Family Reunion in Australia 1983 – 2007 Bianca Lowe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Museums and Australia's Greek Textile Heritage

Museums and Australia’s Greek textile heritage: the desirability and ability of State museums to be inclusive of diverse cultures through the reconciliation of public cultural policies with private and community concerns. Ann Coward Bachelor of General Studies (BGenStud) Master of Letters, Visual Arts & Design (MLitt) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art History and Theory College of Fine Arts University of New South Wales December, 2006 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed .................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the desirability of Australia’s State museums to be inclusive of diverse cultures. In keeping with a cultural studies approach, and a commitment to social action, emphasis is placed upon enhancing the ability of State museums to fulfil obligations and expectations imposed upon them as modern collecting institutions in a culturally diverse nation. -

Vietnamese Identities in Modern Australia

A Quintessential Collision: critical dimensions of the Vietnamese presence in the Australia empire project Andrew Jakubowicz University of Technology Sydney Cultures in Collision Colloqium Transforming Cultures UTS May 9 2003 Abstract The Vietnamese arrival and integration into Australia represents a quintessential case of cultures in collision. In 1975 there was effectively no Vietnamese presence. Over the next twenty five years the community grew to over two hundred thousand members. Before 1975 Vietnam and Australia barely knew each other – except through the prism of the American War. By 2001 Generation 2 were a significant part of Australian political, economic and cultural life. The Vietnamese were used as the trigger for the end of the bi-partisanship on multiculturalism at the end of the 1970s, were implicated in the rising paranoia about unsafe cities in the 1980s, and centrally embroiled in the emergence of a politics of race in the 1990s. They also reflect two trajectories of integration – the anomie associated with marginalization, and the trans-national engagement associated with globalizing elites. This paper explores processes of cultural collision and reconstitution through an examination of three dimensions of the Vietnamese in Australia - the criminal world of the heroin trade; the rise and fall of Phuong Ngo; and the celebration of Generation 2. Note: this is a draft for discussion. Full references in final paper Introduction In July 2002 three young men of Vietnamese background died in an attack by a group of five young men of similar background outside a Melbourne nightclub. The tragedy was fully reported in The Age newspaper, which also was careful to refrain from using ethnic descriptors in presenting the facts of the case. -

Partnering in Action – Annual Report 2018

A brief history of the DISABILITY SERVICES SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA: 1992 – PRESENT DAY Lesley Chenoweth AO Emeritus Professor Griffith University ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was commissioned by Life Without Barriers. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DISABILITY SERVICES SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA: 1992 – PRESENT DAY | 1 CONTENTS List of figures and tables 2 8. Towards a National Disability Insurance Scheme 27 Glossary of terms 2 Australia 2020 27 1. Introduction 3 Productivity Commission Report 27 The brief 3 Money/Funding 28 Methodology 3 Implementation issues 29 How to read this report 4 9. Market Failure? 30 Overview of sections 5 10. Conclusion 31 Limitations of this report 5 References 32 2. Deinstitutionalisation 6 Appendix A 37 3. Shift to the community and supported living 10 Separation of housing and support 10 Appendix B 41 Supported living 11 Appendix C 44 Unmet need 12 Appendix D 45 4. Person-centred planning 14 Appendix E 46 5. Local Area Coordination 16 6. Marketisation 20 7. Abuse, Violence and Restrictive practices 23 Institutionalised settings 23 Complex needs and challenging behaviour 24 Restrictive practices 24 Incarceration and Domestic Violence 26 2 | A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DISABILITY SERVICES SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA: 1992 – PRESENT DAY LIST OF FIGURES GLOSSARY OF TERMS AND TABLES CSDA Commonwealth/State Disability Agreements Figure 1 Demand vs funding available 12 DSA Disability Services Act 1986 Table 1 Restrictive practices DDA Disability Discrimination Act 1992 authorisation summary 25 CAA Carers Association of Australia NGO Non-Government Organisation PDAA People with Disabilities Australia DSSA Disability and Sickness Support Act 1991 | 3 1. INTRODUCTION The brief Methodology Life Without Barriers requested an historical overview The approach to the research consisted of several distinct of the national disability sector from approximately 1992 but interrelated phases: to present including: • Key federal and state-based legislation and policies 1. -

``Citizenship from Below'' Among ``Non-White'' Minorities in Australia

“Citizenship from below” among “non-white” minorities in Australia: Intergroup relations in a northern suburb of Adelaide Ritsuko Kurita To cite this version: Ritsuko Kurita. “Citizenship from below” among “non-white” minorities in Australia: Intergroup relations in a northern suburb of Adelaide. Anthropological Notebooks , Slovenian Anthropological Society, 2020. halshs-03115973 HAL Id: halshs-03115973 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03115973 Submitted on 20 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ‘Citizenship from Below’ Among ‘Non-White’ Minorities in Australia: Intergroup Relations in a Northern Suburb of Adelaide Ritsuko Kurita Associate professor, Faculty of Foreign Languages, Department of English, Kanagawa University [email protected] Abstract The recent scholarship on citizenship has highlighted the significance of horizontal citizenship, which states how an individual’s eligibility for membership is determined by a social system formed by equal peers and the development of a community who share a citizen’s sense of belonging. However, researchers have paid scant attention to the sense of citizenship evinced by marginalised ethnic minorities. The present investigation examines citizenship in Australia by exploring intergroup relations. It attempts to determine the feeling of belonging that connects the Indigenous people of Australia to other ‘non-white’ groups considered ’un-Australian’ by the mainstream society. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1985

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly TUESDAY, 27 AUGUST 1985 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy Papers 27 August 1985 141 TUESDAY, 27 AUGUST 1985 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. J. H. Wamer, Toowoomba South) read prayers and took the chair at 11 a.m. ASSENT TO BILL Appropriation Bill (No. 1) Mr SPEAKER: I have to report that on 23 August 1985 I presented to His Excellency the Govemor Appropriation Bill (No. 1) for the Royal Assent and that His Excellency was pleased, in my presence, to subscribe his assent thereto in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty. PETITIONS The Clerk announced the receipt of the following petitions— Minimum Penalties for Child Abuse From Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen (2 637 signatories) praying that the Parliament of Queensland wiU set down minimum penalties for child abuse. Third-party Insurance Premiums From Mr Warburton (40 152 signatories) praying that the Parliament of Queensland will revoke the recent increases in third-party insurance and ensure that future increases be determined after public hearing. Petitions received. PAPERS The following papers were laid on the table— Proclamations under— Foresty Act 1959-1984 Constmction Safety Act Amendment Act 1985 State Enterprises Acts Repeal Act 1983 Eraser Island Public Access Act 1985 Orders in Council under— Legislative Assembly Act 1867-1978 Forestry Act 1959-1984 Harbours Act 1955-1982 and the Statutory Bodies Financial Arrangements Act 1982-1984 Workers' Compensation Act 1916-1983 Auctioneers and Agents Act 1971-1981 Supreme Court Act of -

A Peaceful Mind: Vietnamese-Australians with Liver Cancer

A peaceful mind: Vietnamese-Australians with liver cancer Interview report Max Hopwood & Carla Treloar Centre for Social Research in Health The University of New South Wales December 2013 1 Summary: Participants indicated little desire for detailed information about liver cancer. Family doctors and liver specialists were the primary sources of information about liver cancer. The internet was another source of liver cancer-related information. DVDs, print resources and Australian/Vietnamese media were not considered to be good sources of liver cancer-related information. Participants relied upon interpreters for understanding the information and advice given by doctors and specialists. Culture and family had a large influence over dietary decisions. Unemployment and under-employment as a result of illness created financial stress for participants. Participants borrowed money from friends and family when necessary. Coping with liver cancer was facilitated by a focus on keeping a peaceful mind. Strategies to consider: On the basis of interview findings derived from this small sample of Vietnamese- Australian liver cancer patients, the following strategies might be considered: Liaising with Vietnamese community medical practitioners to discuss ways of supporting family doctors and liver specialists to ensure patients receive adequate levels of information about living with liver cancer and treatment options. A review of Vietnamese language websites for people with liver cancer, and a compilation of URL addresses of the best site(s) for dissemination via Vietnamese media, community family doctors and liver cancer specialists. A review of interpretation services for Vietnamese people with an aim to publish an online directory and printed directory in the Vietnamese media. -

Vietnamese- Australians with Liver Cancer Interview Report

Arts Social Sciences Centre for Social Research in Health A peaceful mind: Vietnamese- Australians with liver cancer Interview report December 2016 Max Hopwood1, Monica C. Robotin2, Mamta Porwal2, Debbie Nguyen2, Minglo Sze3, Jacob George4, Carla Treloar1 1Centre for Social Research in Health, UNSW Sydney; 2Cancer Council NSW; 3School of Psychology, University of Sydney; 4Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney & Storr Liver Centre, Westmead Hospital Summary • Participants indicated little desire for detailed information about liver cancer. • Family doctors and liver specialists were the primary sources of information about liver cancer. • The internet was another source of liver cancer-related information. • DVDs, print resources and Australian/Vietnamese media were not considered to be good sources of liver cancer-related information. • Participants relied upon interpreters for understanding the information and advice given by doctors and specialists. • Culture and family had a large influence over dietary decisions. • Unemployment and under-employment as a result of illness created financial stress for participants. • Participants borrowed money from friends and family when necessary. • Coping with liver cancer was facilitated by a focus on keeping a peaceful mind. Strategies to consider On the basis of interview findings derived from this small sample of Vietnamese-Australian liver cancer patients, the following strategies might be considered: • Liaising with Vietnamese community medical practitioners to discuss ways of supporting family doctors and liver specialists to ensure patients receive adequate levels of information about living with liver cancer and treatment options. • A review of Vietnamese language websites for people with liver cancer, and a compilation of URL addresses of the best site(s) for dissemination via Vietnamese media, community family doctors and liver cancer specialists. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

Yet We Are Told That Australians Do Not Sympathise with Ireland’

UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE ‘Yet we are told that Australians do not sympathise with Ireland’ A study of South Australian support for Irish Home Rule, 1883 to 1912 Fidelma E. M. Breen This thesis was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Research in the Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. September 2013. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .............................................................................................. 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 4 Declaration ........................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. 6 ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 7 CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 WHAT WAS THE HOME RULE MOVEMENT? ................................................................. 17 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE .................................................................................... -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

Religion, Cultural Diversity and Safeguarding Australia

Cultural DiversityReligion, and Safeguarding Australia A Partnership under the Australian Government’s Living In Harmony initiative by Desmond Cahill, Gary Bouma, Hass Dellal and Michael Leahy DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS and AUSTRALIAN MULTICULTURAL FOUNDATION in association with the WORLD CONFERENCE OF RELIGIONS FOR PEACE, RMIT UNIVERSITY and MONASH UNIVERSITY (c) Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2004 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Intellectual Property Branch, Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or at http:www.dcita.gov.au The statement and views expressed in the personal profiles in this book are those of the profiled person and are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth, its employees officers and agents. Design and layout Done...ByFriday Printed by National Capital Printing ISBN: 0-9756064-0-9 Religion,Cultural Diversity andSafeguarding Australia 3 contents Chapter One Introduction . .6 Religion in a Globalising World . .6 Religion and Social Capital . .9 Aim and Objectives of the Project . 11 Project Strategy . 13 Chapter Two Historical Perspectives: Till World War II . 21 The Beginnings of Aboriginal Spirituality . 21 Initial Muslim Contact . 22 The Australian Foundations of Christianity . 23 The Catholic Church and Australian Fermentation . 26 The Nonconformist Presence in Australia . 28 The Lutherans in Australia . 30 The Orthodox Churches in Australia . -

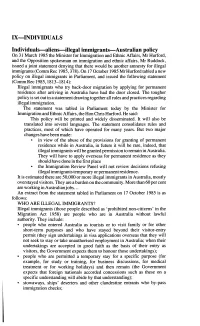

IX-INDIVIDUALS Individuals-Aliens-Illegal Immigrants

IX-INDIVIDUALS Individuals-aliens-illegal immigrants-Australian policy On 3 1 March 1985 the Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Mr Hurford, and the Opposition spokesman on immigration and ethnic affairs, Mr Ruddock, issued a joint statement denying that there would be another amnesty for illegal immigrants (Comm Rec 1985,378). On 17 October 1985 Mr Hurford tabled anew policy on illegal immigrants in Parliament, and issued the following statement (CommRec 1985,1813-1814): Illegal immigrants who try back-door migration by applying for permanent residence after arriving in Australia have had the door closed. The tougher policy is set out in a statement drawing together all rules and practices regarding illegal immigration. The statement was tabled in Parliament today by the Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, the Hon Chris Hurford. He said: This policy will be printed and widely disseminated. It will also be translated into several languages. The statement consolidates rules and practices, most of which have operated for many years. But two major changes have been made: in view of the abuse of the provisions for granting of permanent residence while in Australia, in future it will be rare, indeed, that illegal immigrants will be granted permission to remain in Australia. They will have to apply overseas for permanent residence as they should have done in the first place the Immigration Review Panel will not review decisions refusing illegal immigrants temporary or permanent residence. It is estimated there are 50,000 or more illegal immigrants in Australia, mostly overstayed visitors. They are a burden on the community.