Tricolored Bat Perimyotis Subflavus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bat Conservation 2021

Bat Conservation Global evidence for the effects of interventions 2021 Edition Anna Berthinussen, Olivia C. Richardson & John D. Altringham Conservation Evidence Series Synopses 2 © 2021 William J. Sutherland This document should be cited as: Berthinussen, A., Richardson O.C. and Altringham J.D. (2021) Bat Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Interventions. Conservation Evidence Series Synopses. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Cover image: Leucistic lesser horseshoe bat Rhinolophus hipposideros hibernating in a former water mill, Wales, UK. Credit: Thomas Kitching Digital material and resources associated with this synopsis are available at https://www.conservationevidence.com/ 3 Contents Advisory Board.................................................................................... 11 About the authors ............................................................................... 12 Acknowledgements ............................................................................. 13 1. About this book ........................................................... 14 1.1 The Conservation Evidence project ................................................................................. 14 1.2 The purpose of Conservation Evidence synopses ............................................................ 14 1.3 Who this synopsis is for ................................................................................................... 15 1.4 Background ..................................................................................................................... -

Forest Management and Bats

F orest Management a n d B a t s | 1 Forest Management and Bats F orest Management a n d B a t s | 2 Bat Basics More than 1,400 species of bats account for almost a quarter of all mammal species worldwide. Bats are exceptionally vulnerable to population losses, in part because they are one of the slowest-reproducing mammals on Earth for their size, with most producing only one young each year. For their size, bats are among the world’s longest-lived mammals. The little brown bat can live up to 34 years in the wild. Contrary to popular misconceptions, bats are not blind and do not become entangled in human hair. Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. Most bat species use an extremely sophisticated biological sonar, called echolocation, to navigate and hunt for food. Some bats can detect an object as fine as a human hair in total darkness. Worldwide, bats are a primary predator of night-flying Merlin Tuttle insects. A single little brown bat, a resident of North American forests, can consume 1,000 mosquito-sized insects in just one hour. All but three of the 47 species of bats found in the United States and Canada feed solely on insects, including many destructive agricultural pests. The remaining bat species feed on nectar, pollen, and the fruit of cacti and agaves and play an important role in pollination and seed dispersal in southwestern deserts. The 15 million Mexican free-tailed bats at Bracken Cave, Texas, consume approximately 200 tons of insects nightly. -

Bat Damage Ecology & Management

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE IN WISCONSIN: SOLVING NUISANCE, DAMAGE, HEALTH & SAFETY PROBLEMS – G3997-012 Bat Damage Ecology & Management As the world’s only true flying mammal, bats have extremely interesting lifestyles. They belong to the order Chiroptera, S W F S U – which means “hand wing.” There are s t a b n w ro approximately 1,400 species of bats world- b le tt li g in at wide, with 47 species residing in the United n er ib States. Wisconsin was home to nine bat species H at one time (there was one record of the Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis, in Wisconsin), but only eight species are currently found in the state. Our Wisconsin bats are a diverse group of animals that are integral to Wisconsin’s well-being. They are vital contributors to the welfare of Wisconsin’s economy, citizens, and ecosystems. Unfortunately, some bat species may also be in grave danger of extinction in the near future. DESCRIPTION “Wisconsin was home to nine bat species at one time, but All Wisconsin’s bats have only eight species are currently found in the state. egg-shaped, furry bodies, ” large ears to aid in echolo- cation, fragile, leathery wings, and small, short legs and feet. Our bats are insectivores and are the primary predator of night-flying insects such as mosquitoes, beetles, moths, and June bugs. Wisconsin’s bats are classified The flap of skin as either cave- or tree- connecting a bat’s legs is called the dwelling; cave-dwelling bats uropatagium. This hibernate underground in structure can be used as an “insect caves and mines over winter net” while a bat is feeding in flight. -

Information Synthesis on the Potential for Bat Interactions with Offshore Wind Facilities

_______________ OCS Study BOEM 2013-01163 Information Synthesis on the Potential for Bat Interactions with Offshore Wind Facilities Final Report U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Renewable Energy Programs www.boem.gov OCS Study BOEM 2013-01163 Information Synthesis on the Potential for Bat Interactions with Offshore Wind Facilities Final Report Authors Steven K. Pelletier Kristian S. Omland Kristen S. Watrous Trevor S. Peterson Prepared under BOEM Contract M11PD00212 by Stantec Consulting Services Inc. 30 Park Drive Topsham, ME 04086 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Herndon, VA Office of Renewable Energy Programs June 2013 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared under contract between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and Stantec Consulting Services Inc. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of BOEM, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. It is, however, exempt from review and compliance with BOEM editorial standards. REPORT AVAILABILITY The report may be downloaded from the boem.gov website through the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS). You will be able to obtain this report from BOEM or the National Technical Information Service. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Ocean Energy Management National Technical Information Service Office of Renewable Energy Programs 5285 Port Royal Road 381 Elden Street, HM-1328 Springfield, Virginia 22161 Herndon, VA 20170 Phone: (703) 605-6040 Fax: (703) 605-6900 Email: [email protected] CITATION Pelletier, S.K., K. -

Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections

Prepared by the USGS National Wildlife Health Center Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover photo (D.G. Constantine) A Townsend’s big-eared bat. Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections By Denny G. Constantine Edited by David S. Blehert Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Constantine, D.G., 2009, Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections: Reston, Va., U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1329, 68 p. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Constantine, Denny G., 1925– Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections / by Denny G. Constantine. p. cm. - - (Geological circular ; 1329) ISBN 978–1–4113–2259–2 1. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Florida's Bats: Tricolored Bat1

WEC389 Florida’s Bats: Tricolored Bat1 Emily Evans, Terry Doonan, and Holly K. Ober2 The tricolored bat, formerly known as the eastern pipistrelle, is the smallest bat found in the state of Florida (Figure 1). It weighs just 0.3 ounces or 8 grams (the weight of a nickel and a penny) and has an approximately 9-inch (210–260 mm) wingspan. Due to their small size and erratic flight pattern, tricolored bats are often mistaken for moths when seen in flight from a long distance away. Figure 2. Tricolored bats are found throughout the state of Florida, except the Keys. This species is considered one of the more colorful species Figure 1. Tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus). Note the multi-colored of bats in the state. They have pinkish forearms (the bones strands of fur. Credits: Merlin Tuttle, Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation that support the wings), black wing membranes, and fur ranging from silver-yellow to dark orange. The name refers Tricolored bats are found throughout the eastern United to the three colors (black, yellow, and brown) found on States and Central America and are known to occur in most individual hairs on the bat’s body (Figure 3). areas of Florida, with the exception of the Keys (Figure 2). Since they are rarely encountered within the state, tricol- ored bats are considered uncommon in Florida. 1. This document is WEC389, one of a series of the Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date November 2017. Visit the EDIS website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Bat Conservation Plan SOUTH CAROLINA

SOUTH CAROLINA Bat Conservation Plan South Carolina Department of Natural Resources SOUTH CAROLINA BAT CONSERVATION PLAN Updated July 2019 Prepared by: Jennifer R. Kindel Wildlife Biologist South Carolina Department of Natural Resources 124 Wildlife Drive Union, SC 29379 This is the South Carolina Bat Conservation Plan. It has been revised and updated from the initial plan created in September 2015. This plan provides information on legal status, public health, conservation issues, natural history, habitat requirements, species-specific accounts, threats and conservation strategies for bat species known to occur in the state. The primary purpose of this plan is to summarize available information for these species and provide proactive strategies in order to help guide management and conservation efforts. Suggested citation: South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. 2019. South Carolina Bat Conservation Plan. Columbia, South Carolina. 204 pp. Cover photo by Mary Bunch Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... v Purpose .............................................................................................................................................................................. v Bat Species in South Carolina................................................................................................................................ -

Occurrence and Suspected Function of Prematernity Colonies of Eastern Pipistrelles, Perimyotis Subflavus, in Indiana

2014. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 123(1):49–56 OCCURRENCE AND SUSPECTED FUNCTION OF PREMATERNITY COLONIES OF EASTERN PIPISTRELLES, PERIMYOTIS SUBFLAVUS, IN INDIANA John O. Whitaker, Jr.1 and Brianne L. Walters: Center for Bat Research, Outreach, and Conservation, Department of Biology, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809, USA Jacques Pierre Veilleux: Department of Biology, Franklin Pierce University, Rindge, NH 03461, USA Richard O. Davis: Clifty Falls State Park, Madison, IN 47250, USA ABSTRACT. During summer, some pregnant female Eastern Pipistrelles form colonies in buildings but most typically roost in clusters of live or dead leaves in trees. We provide evidence that some that ultimately roost in leaf clusters form temporary colonies in or on buildings in early spring, prior to moving to the leaf clusters where they give birth. We call these prematernity colonies, and define them as those formed for a short time following hibernation and before the bats move to their maternity roosts. Prematernity colonies form from late April to early May and individuals relocate to leaf clusters from late May to early June. The bats showed strong fidelity to prematernity roosts, returning annually. Time of occupancy during any one year averaged 26 days. Nine bats were radio-tracked during the transition from building to tree roosts and were found to use several different trees. Bats showed interannual fidelity to building roosts. Buildings may help colonies re-form after individuals migrate from their hibernacula. Also, they could provide a warmer or more stable microclimate for pregnant females. Keywords: Bats, bat roosts, Eastern Pipistrelles, prematernity colonies INTRODUCTION trelles (Perimyotis subflavus) (F. -

Tri-Colored Bat (Perimyotis Subflavus) in Ontario

Photos: Jordi Segers Little Brown Myotis Northern Myotis Tri-colored Bat Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus), Northern Myotis (Myotis septentrionalis), Tri-colored Bat (Perimyotis subflavus) in Ontario Ontario Recovery Strategy Series 2019 Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada. What is recovery? What’s next? Recovery of species at risk is the process by Nine months after the completion of a recovery which the decline of an endangered, threatened, strategy a government response statement will or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, be published which summarizes the actions that and threats are removed or reduced to improve the Government of Ontario intends to take in the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the response to the strategy. The implementation of wild. recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and What is a recovery strategy? conservationists. Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A For more information recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs To learn more about species at risk recovery in and the threats to the survival and recovery of Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Environment, the species. -

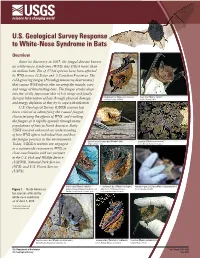

U.S. Geological Survey Response to White-Nose Syndrome in Bats

U.S. Geological Survey Response to White-Nose Syndrome in Bats Overview Since its discovery in 2007, the fungal disease known as white-nose syndrome (WNS) has killed more than six million bats. Ten of 47 bat species have been affected by WNS across 32 States and 5 Canadian Provinces. The cold-growing fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) that causes WNS infects skin covering the muzzle, ears, and wings of hibernating bats. The fungus erodes deep into the vitally important skin of bat wings and fatally Big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) Cave bat (Myotis velifer) disrupts hibernation of bats through physical damage Ann Froschauer, USFWS Public Domain, NPS and energy depletion as they try to cope with infection. U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) science has been critical in identifying the causal fungus, characterizing the effects of WNS, and tracking the fungus as it rapidly spreads through many populations of bats in North America. Early USGS research enhanced our understanding of how WNS affects individual bats and how the fungus persists in the environment. Eastern small-footed bat (Myotis leibii ) Gray bat (Myotis grisescens)1 Today, USGS scientists are engaged Virginia State Parks Larisa Bishop-Boros, CC license in a nationwide response to WNS, in close coordination with our partners at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Park Service (NPS), and U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis)1 Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) Northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis)2 Figure 1. North American Andrew Kniowski, Department of Fish and Alan Hicks, NY Department of Pete Patavino, USFWS Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Tech Environmental Conservation bat species affected by white-nose syndrome https://github.com/USGS-R/BatTool as of June 1, 2018.