Beliefs in Progress: the Beguins of Languedoc and the Construction of a New Heretical Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Fort of Montaillou Confession 36

Guillaume Fort of Montaillou Confession 36 Confession of Guillaume Fort of Montaillou In the year 1321, the Monday before Palm Sunday (April 6, 1321) a letter of citation was sent by the Reverend Father in Christ my lord Jacques, by the grace of God bishop of Pamiers, the tenor of which follows: !“Brother Jacques, by divine grace the bishop of Pamiers, to his dear vicar in Christ in Montaillou, Raimond Trilhe, greetings in the Lord. !Since for very plausible causes and strong presumptions we hold the following strongly suspect of heresy: Bernard Clergue, Guillaume Fort, Guillemette Benet, Esclarmonde, the wife of Raimond Clergue, Vuissane, the wife of Bernard Testanière and Raimonde, the wife of the said Bernard Clergue and since we wish and intend, insofar as we are charged to do so, to investigate them concerning the faith, we order you to cite these named persons at once to appear before us this coming Saturday in our episcopal seat of Pamiers before tierce, to answer concerning the above-mentioned facts concerning the faith, and there to proceed in this matter as is appropriate, signifying to them that if they do not appear on this day before us, we will proceed against them as against those suspect in heresy, according to the law, notwithstanding their absence. !Given in our episcopal seat, the Monday before Palm Sunday, the year of the Lord 1321. Return the letter with a seal as a sign of this accomplished mandate.” !On the Saturday assigned in this letter of citation, appearing were Guillaume Fort, Esclarmonde, the wife of Raimond Clergue, and Vuissane, the wife of Bernard Testanière, who had been cited by the vicar of Montaillou for this Saturday, conforming to the content of the above-mentioned letter, since this citation was completed by the placement of the seal of the vicar, put onto this letter as a sign of the accomplishment of his mandate. -

Annexe1 RETENUES COLLINAIRES 2020.Pdf

ANNEXE 1 – Plan de Répartition 2020 – Période d’étiage – Retenues collinaires – Sous-bassin Ariège Identification du Identification Surface Volume Nom Prénom Commune Type de préleveur (nom Adresse C.P Commune Lieu dit Département de la déclarée Autorisé bénéficiaire bénéficiaire prélèvement prélèvement de l'exploitation) ressource 2020 (ha) 2020 (m3) 694 chemin BEAUMONT- BEAUMONT- pompage sur ASA DE LA LANTINE CHIBARIE Jean Claude 31870 Lac de la Lantine Haute-Garonne retenue collinaire 50,00 180 000 d'espinaouet SUR-LEZE SUR-LEZE plan d'eau champs de la pompage sur ASA DE SEIGNALENS VERISSE Alexandre 11420 SEIGNALENS Le barry SEIGNALENS Aude retenue collinaire 76 000 ville plan d'eau champs de la pompage sur ASA DE SEIGNALENS VERISSE Alexandre 11420 SEIGNALENS Fontassaut SEIGNALENS Aude retenue collinaire 69 000 ville plan d'eau ASA DES IRRIGANTS ADELLACH – pompage sur Mairie 09100 UNZENT Lac de la Laure LESCOUSSE Ariège retenue collinaire 75 000 DE LA LAURE VEROT plan d'eau Saint-Geniès, pompage sur ASL CANTO CLAOU DE SOLAN André Saint-Geniès 09130 CARLA-BAYLE ruisseau de canto CARLA-BAYLE Ariège retenue collinaire 25,00 200 000 plan d'eau claou SICA Irrigation est CASTELNAUD PECHARIC-ET- pompage sur ASL DU RIEUTORD Loudès 11451 Rieutord Aude retenue collinaire 250 000 audois ARY LE-PY plan d'eau 716, chemin de BEAUMONT- BEAUMONT- pompage sur ASL LE PORT GERBER Christian 31870 Ribonnet Haute-Garonne retenue collinaire 147,00 45 000 Ribaunet SUR-LEZE SUR-LEZE plan d'eau Joulé, ruisseau de pompage sur BONADEI Francis Joulé 09130 CARLA-BAYLE -

Scènes D'enfance

Semaine Audoise du spectacle jeune public ScèneS d’enfAnce du 15 au S 30 mAr 2011 www.cg11.fr/scenesdenfance Théâtre d’ombres uit TArIf le 15 Grat UNIQUE ArS l’ENF leS m AnT d’Él AnS 5€ ÉPhAn d S eT AuTRE T iathèque 150 places S cOn Éd rÉSERVATIO Te m n durée : 1h mardi 15 marsS - 18h30 - Édition 2011 CoN Pennautier - Théâtre na l SeILLÉe u à partir de 6 ans ÉdITO oba Spectacle composé à partir de 4 histoires : l’enfant Ouvrir de nouveauxconseil horizons Général aux de jeunes l’Aude Audois, au travers tel de nfance initiée en 2007. d’éléphant, Pierre et le est l’objectif du loup, histoire de la belle l’opération Scènes d’e grenouille et du jeune depuis, chaque édition permet à de nombreux jeunes crapaud et “la grenouille spectateurs d’assister à des représentations de théâtre, qui se veut faire aussi musique, cirque, danse, marionnettes et de rencontrer des grosse que le boeuf” (fable artistes. de la fontaine). Grâce à un partenariat exemplaire avec les acteurs des scènes et réseaux de diffusion audois et les médiathèques compagnie le Théâtre des Ombres. et bibliothèques de l’Aude, le spectacle vivant donne rendez- vous aux jeunes et aux moins jeunes du 15 au 30 mars pour partir à la découverte de 31 spectacles présentés partout dans l’Aude à l’occasion des 46 séances tout public. 50 places Il y a forcément un joli moment artistique à vivre près de durée :1 h leS 17, chez vous. Je m’associe à tous les organisateurs de cette u à partir de 6 ans Théâtre nouvelle édition pour vous souhaiter bonne découverte, 18 eT belles émotions et grands plaisirs. -

ANNEXE 1 - Plan De Répartition 2021 - Période Étiage - Retenues Collinaires -Périmètre 66 1/57

ANNEXE 1 - Plan de répartition 2021 - Période étiage - Retenues collinaires -Périmètre 66 1/57 Identification du Surface Volume Commune identification de Volume de la préleveur (nom de Nom Prénom Adresse C.P Commune Lieu-dit Département déclarée 2021 Attribué 2021 prélèvement la ressource retenue (m3) l'exploitation) (ha) (m3) Jean- 694 chemin BEAUMONT-SUR- Lac de la BEAUMONT-SUR- retenue ASA DE LA LANTINE CHIBARIE 31870 Haute-Garonne 180 000 50,00 180 000 Claude d'espinaouet LEZE Lantine LEZE collinaire champs de la retenue ASA DE SEIGNALENS Vénisse Alexandre 11420 SEIGNALENS Le barry SEIGNALENS Aude 76 000 23,70 76 000 ville collinaire Adellach, ASA DES IRRIGANTS Lac de la retenue Vérot, Petit, Mairie 09100 UNZENT LESCOUSSE Ariège 75 000 40,00 75 000 DE LA LAURE Laure collinaire Egay, Delrieu Saint- Geniès, retenue ASL CANTO CLAOU GIORDANO Gaël Icart 09130 SIEURAS CARLA-BAYLE Ariège 200 000 15,00 200 000 ruisseau de collinaire canto claou SICA irrigation PECHARIC-ET-LE- retenue ASL DU RIEUTORD Loudès 11451 CASTELNAUDARY Rieutord Aude 250 000 104,00 250 000 ouest-audois PY collinaire 716, chemin de BEAUMONT-SUR- BEAUMONT-SUR- retenue ASL LE PORT GERBER Christian 31870 Ribonnet Haute-Garonne 45 000 147,00 45 000 Ribaunet LEZE LEZE collinaire Joulé, retenue BONADEI FRANCIS BONADEI Francis Joulé 09130 CARLA-BAYLE ruisseau de CARLA-BAYLE Ariège 45 000 5,00 45 000 collinaire Panissa Mécail, retenue BONADEI FRANCIS BONADEI Francis Joulé 09130 CARLA-BAYLE ruisseau de CARLA-BAYLE Ariège 75 000 30,00 75 000 collinaire la Fount BOSSUT BOSSUT retenue -

L'ouest Audois, Un Territoire Sous Influence Méditerranéenne Et Toulousaine

n° 23 Décembre2005 L’OUESTAUDOIS, UNTERRITOIRESOUSINFLUENCE MÉDITERRANÉENNEETTOULOUSAINE L'aireurbaine(1) deToulouseexploseavecunepopulationd'unmillion d’habitantsetunrenforcementconstantdesoninfluence.Elleagagné87 communesen10ans,dont2communesdudépartementdel'Aude. Cettecroissances'esttraduiteparuneaugmentationdelapopulationde 14000habitantsparandepuis10ans,soitl'équivalentdelavillede Castelnaudary,villesituéedansl'Audeàmoinsde30minutesdeToulouse. L'Ouestaudois,àdominanterurale,doitdoncs'organiserpourtirerbénéficede cettesituation,toutenassurantundéveloppementdurabledesonterritoire JérômeBonavent-DDEdel'Aude serviceAménagementetTerritoires L'Ouestaudois, territoire composéde deuxpays(2) -le Carcassonnaiset leLauragais- s'articuleentre unsillonattractif etunefrange ruraleen mutation. Ilestengrande partiestructuré parses infrastructures routières. (1)Aireurbaine,ausensdeladéfinitionINSEE,soitlepôleurbainetlacouronnepéri-urbaine,constituéeparlescommunesdont40%desactifs travaillentdanslepôleurbainoudanslescommunesattiréesparcelui-ci. (2)Ledécoupagedel'Audeen5Paysestreprisdanscetteétude.L’OuestAudoiscomprendlapartieAudoiseduPaysLauragais,lePays Carcassonnaisetl'agglomérationdeCarcassonne.LePaysdelaHauteVallée,aveclepôleurbaindeLimoux,n'estdoncpastraitédanscette étudecibléesurlesillonAudois,malgrélesliensimportantsentreLimouxetCarcassonne,maisaussiavecCastelnaudary. UNESTRUCTURATIONDEL’ESPACEQUIRÉPONDAUXLOGIQUESDEDÉPLACEMENTSEST-OUEST L'axeprincipalEst-Ouest (envertclairsurla Cesdeuxentitéscoexistentavecdespôles carte)estlevecteurdelamajoritédeséchanges. -

Cheeses Part 2

Ref. Ares(2013)3642812 - 05/12/2013 VI/1551/95T Rev. 1 (PMON\EN\0054,wpd\l) Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92 APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION: Art. 5 ( ) Art. 17 (X) PDO(X) PGI ( ) National application No 1. Responsible department in the Member State: I.N.D.O. - FOOD POLICY DIRECTORATE - FOOD SECRETARIAT OF THE MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FISHERIES AND FOOD Address/ Dulcinea, 4, 28020 Madrid, Spain Tel. 347.19.67 Fax. 534.76.98 2. Applicant group: (a) Name: Consejo Regulador de la D.O. "IDIAZÁBAL" [Designation of Origin Regulating Body] (b) Address: Granja Modelo Arkaute - Apartado 46 - 01192 Arkaute (Álava), Spain (c) Composition: producer/processor ( X ) other ( ) 3. Name of product: "Queso Idiazábaľ [Idiazábal Cheese] 4. Type of product: (see list) Cheese - Class 1.3 5. Specification: (summary of Article 4) (a) Name: (see 3) "Idiazábal" Designation of Origin (b) Description: Full-fat, matured cheese, cured to half-cured; cylindrical with noticeably flat faces; hard rind and compact paste; weight 1-3 kg. (c) Geographical area: The production and processing areas consist of the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country and part of the Autonomous Community of Navarre. (d) Evidence: Milk with the characteristics described in Articles 5 and 6 from farms registered with the Regulating Body and situated in the production area; the raw material,processing and production are carried out in registered factories under Regulating Body control; the product goes on the market certified and guaranteed by the Regulating Body. (e) Method of production: Milk from "Lacha" and "Carranzana" ewes. Coagulation with rennet at a temperature of 28-32 °C; brine or dry salting; matured for at least 60 days. -

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

RADIATIONS DU 1Er AU 31 JUILLET 2020 11890 CARCASSONNE Cédex

Chambre de Métiers et de l'Artisanat de l'Aude Affichage du 1er au 31 août 2020 20 Avenue du Mal Juin - CS 70051 RADIATIONS DU 1er AU 31 JUILLET 2020 11890 CARCASSONNE cédex Date Siret Nom / Dénomination Entreprise radiation Numéro de gestion Activité artisanale Adresse du siège Dirigeants, libellé fonction Forme juridique cessation code APRM 29/07/2020 400.058.079.00049 30/06/2020 5 AVENUE KARL MARX Mohamed AOURIA EXPLOITANT AOURIA MOHAMED 0023917110 SNACK, RESTAURATION RAPIDE 11100 NARBONNE INDIVIDUEL 5610CQ 28/07/2020 348.631.136.00036 3 RUE DE L'ECOLE 29/05/2020 TAXI - LOCATION DE FONDS ET DE Regis ARMENGAUD EXPLOITANT ARMENGAUD REGIS 0079207110 LE SEGALA VEHICULES TAXI INDIVIDUEL 4932ZA 11320 LABASTIDE D'ANJOU 10/07/2020 795.366.400.00013 01/07/2020 SERVICES ADMINISTRATIFS COMBINES 11 RUE DES AMANDIERS Lucette ASTRE EXPLOITANT ASTRE LUCETTE 0034018110 DE BUREAU 11250 ROUFFIAC D AUDE INDIVIDUEL 8211ZP 30/07/2020 27/07/2020 812.468.049.00034 ASSISTANCE, MAINTENANCE, 6 RUE DU MARCHE Tristan BERENGER EXPLOITANT BERENGER TRISTAN 0064915110 REPARATIONS D'ORDINATEURS, 11400 CASTELNAUDARY INDIVIDUEL 9511ZZ TABLETTES ET TELEPHONES 10/07/2020 328.172.010.00014 30/06/2020 1 RUE BAPTISTE LIMOUZY Jean-Francois BIELSA EXPLOITANT BIELSA JEAN-FRANCOIS 0055883110 RECHAPAGE REP.INDUS.PNEUMATIQUE 11100 NARBONNE INDIVIDUEL 2211ZZ 15/07/2020 BORDE ET FILS 752.068.759.00014 25/02/2020 4 RUE DU PORT AUTRE SOCIETE A 0085412110 SANS ACTIVITE Philippe BORDE LIQUIDATEUR 11120 GINESTAS RESPONSABILITE LIMITEE 5610CQ 24/07/2020 449.200.211.00034 ROUTE DE FONTIERS -

Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/2460

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/2460. (See end of Document for details) Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/2460 of 23 December 2015 concerning certain protective measures in relation to highly pathogenic avian influenza of subtype H5 in France (notified under document C(2015) 9818) (Only the French text is authentic) (Text with EEA relevance) COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION (EU) 2015/2460 of 23 December 2015 concerning certain protective measures in relation to highly pathogenic avian influenza of subtype H5 in France (notified under document C(2015) 9818) (Only the French text is authentic) (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Directive 89/662/EEC of 11 December 1989 concerning veterinary checks in intra-Community trade with a view to the completion of the internal market(1), and in particular Article 9(4) thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 90/425/EEC of 26 June 1990 concerning veterinary and zootechnical checks applicable in intra-Community trade in certain live animals and products with a view to the completion of the internal market(2), and in particular Article 10(4) thereof, Whereas: (1) Avian influenza is an infectious viral disease in birds, including poultry. Infections with avian influenza viruses in domestic poultry cause two main forms of that disease that are distinguished by their virulence. The low pathogenic form generally only causes mild symptoms, while the highly pathogenic form results in very high mortality rates in most poultry species. -

Retrieving a Catholic Tradition of Subjective Natural Rights from the Late Scholastic Francisco Suárez, S.J

Copyright © 2012 Ave Maria Law Review RETRIEVING A CATHOLIC TRADITION OF SUBJECTIVE NATURAL RIGHTS FROM THE LATE SCHOLASTIC FRANCISCO SUÁREZ, S.J. Steven J. Brust, Ph.D. g INTRODUCTION There is good reason to inquire into the Catholic contributions to the foundation of human rights.1 There is a global proliferation of natural rights in nation-states, international treaties, charters and conventions, as well as in political rhetoric, court decisions, law, and even in personal conversation. Furthermore, the Catholic Church herself has emerged as one of the leading advocates of natural rights in its moral and social teachings as well as in its charitable practices. As a result of these omnipresent rights claims, debates have arisen with respect to the origin and nature of, and justification for, natural rights. These debates are not only between Catholics and those outside the Church (e.g., with contemporary secular liberals), but also between Catholics themselves. At the heart of these debates are a number of questions: Do natural rights even exist? If so, what is a right? Are natural rights compatible with or contradictory to natural law understood as an objective order of justice? Are natural rights derived from natural law or is natural law derived from natural rights? Which is given a priority? Do natural rights entail a rejection or diminution of virtue and the common good? For some Catholics, a very important aspect of this overall debate is the supposed break between pre-modern views on natural right/law and modern views on natural rights. They offer a narrative which includes the claim that rights are more of an invention of the modern political philosophers such as Hobbes and Locke, and/or have their g Steven J. -

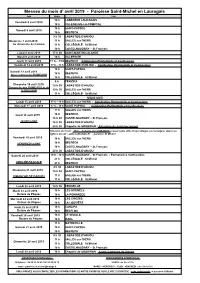

Messes Du Mois D' Avril 2019

Messes du mois d' avril 2019 - Paroisse Saint-Michel en Lauragais Jour Heure Lieu 18 h LABÉCÈDE LAURAGAIS Vendredi 5 avril 2019 18 h VILLENEUVE-LA-COMPTAL 18 h SAINT-PAPOUL Samedi 6 avril 2019 18 h BELPECH 9 h 30 LABASTIDE D'ANJOU Dimanche 7 avril 2019 11 h SALLES sur l'HERS 5e dimanche de Carême 11 h COLLÉGIALE St Michel 18 h CASTELNAUDARY – St François Lundi 8 avril 2019 17 h 30 SAINT-MARTIN LALANDE Mardi 9 avril 2019 18 h VILLEPINTE Jeudi 11 avril 2019 17 h – 19 h BELPECH - Célébration Pénitentielle et Confessions Vendredi 12 avril 2019 17 h – 19 h LABASTIDE D'ANJOU - Célébration Pénitentielle et Confessions 18 h SAINT-PAPOUL Samedi 13 avril 2019 18 h BELPECH Messe anticipée des RAMEAUX 18 h COLLÉGIALE St Michel 9 h PEXIORA Dimanche 14 avril 2019 10 h 30 LABASTIDE D'ANJOU Dimanche des RAMEAUX et de la PASSION 10 h 30 SALLES sur l'HERS 11 h COLLÉGIALE St Michel SEMAINE SAINTE Lundi 15 avril 2019 17 h – 19 h SALLES sur l'HERS - Célébration Pénitentielle et Confessions Mercredi 17 avril 2019 17 h – 19 h SAINT-PAPOUL - Célébration Pénitentielle et Confessions 17 h SALLES sur l'HERS 'Jeudi 18 avril 2019 18 h BELPECH 18 h 30 CASTELNAUDARY – St François JEUDI SAINT 18 h 30 LABASTIDE D'ANJOU 20 h 30 Chapelle de SOUBIRAN : Adoration du Saint-Sacrement Chemins de Croix : 15 h - Calvaire de LAURABUC et pour votre ville et vos villages se renseigner dans vos églises ou sur : aude.catholique.fr → paroisse St Michel Vendredi 19 avril 2019 18 h SALLES sur l'HERS VENDREDI SAINT 18 h BELPECH 18 h CASTELNAUDARY – St François 20 h 30 LABASTIDE D'ANJOU -

Canonical Elections

<? O , o " c * 4 o c0^ c^:=.,^o^ ^-^^ .'/J^.^ ^^ ^.* ^^ -^"^ H Ct3 CANONICAL ELECTIONS Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF CANON LAW By DANIEL M. GALLIHER, O. P., J. C. L. Catholic University of America J9J7 CANONICAL ELECTIONS Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF CANON LAW By DANIEL M. GALLIHER, O. P., J, C L. Catholic University of America J9J7 ^v^< iV?7w7 O&^^a^ 4- THOMAS J. SHAHAN, S. T. D., Censor Deputatus. Imprimatur : M. CARD. GIBBONS, Archiepiscopus Baltimorensis. Approbatio Ordinis Nihil Obstat: FR. JOSEPHUS KENNEDY, O. P., S. T. M. FR. AUGUSTINUS WALDRON, O. P., S. T. M. Imprimatur : FR. RAYMUNDUS MEAGHER, O. P., S. T. L., Prior Provincialis. The Rosary Press, Somerset, Ohio 1917 ^ t ^ (^^ CANONICAL ELECTIONS CONTENTS Introduction 5 Historical Concept 7 Juridical Concept 21 Qualifications of Electors 31 Convocation of Electors 45 Persons Eligible 54 The Act of Election 67 Postulation 83 Defects in Election 87 Subsequent Acts 96 Appendix—I. Manner of Electing a Sovereign Pontiff 104 11. Method of Selecting Bishops in the United States 107 Sources and Bibliography Ill — INTRODUCTION There is no institution, perhaps, that occupies a more prom- inent place in the entire history of ecclesiastical legislation than canonical election. For the Church during the almost twenty centuries of her active life has promulgated for no other institu- tion such a vast and varied array of enactments, decrees, and con- stitutions.