Agriculture Connected to Ecosystems and Sustainability: a Palestine World Heritage Site As a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Beit Sahour City Profile

Beit Sahour City Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation Azahar Program 2010 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project through the Azahar Program. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Background This booklet is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in Bethlehem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Bethlehem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) and the Azahar Program. The "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Bethlehem Governorate with particular focus on the Azahar program objectives and activities concerning water, environment, and agriculture. -

Documentation German Palestinian Municipal Partnership Workshop

Documentation German Palestinian Municipal Partnership Workshop Ramallah and Bethlehem 23 November 2014 Imprint Published by: ENGAGEMENT GLOBAL gGmbH – Service für Entwicklungsinitiativen (GLOBAL CIVIC ENGAGEMENT – Service for Development Initiatives) Tulpenfeld 7, 53111 Bonn, Germany Phone +49 228 20 717-0 Ӏ Fax +49 228 20 717-150 [email protected]; www.engagement-global.de Service Agency Communities in the One World [email protected]; www.service-eine-welt.de Text: Petra Schöning Responsible for content: Service Agency Communities in One World, Dr. Stefan Wilhelmy Special thanks go to Mr. Ulrich Nitschke and the GIZ Programmes “Local Governance and Civil Society Development Programme” and “Future for Palestine” for their enormous support in the organization and realization of this workshop. 1 Table of Contents Workshop Schedule ................................................................................................................................. 3 I Objectives .............................................................................................................................................. 4 II Opening Remarks GIZ and Service Agency Communities in One World .............................................. 4 Introduction of GIZ Programmes “Local Governance and Civil Society Development Programme (LGP)” and “Future for Palestine (FfP)” by Ulrich Nitschke (GIZ) ........................................................ 4 Introduction of the Engagement Global Programme “Service Agency Communities in One -

General Assembly Economic and Social Council

United Nations A/67/84–E/2012/68 General Assembly Distr.: General 8 May 2012 Economic and Social Council Original: English General Assembly Economic and Social Council Sixty-seventh session Substantive session of 2012 Item 71 (b) of the preliminary list* New York, 2-27 July 2012 Strengthening of the coordination of humanitarian and Item 9 of the provisional agenda** disaster relief assistance of the United Nations, including Implementation of the Declaration on the special economic assistance Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples by the specialized agencies and the international institutions associated with the United Nations Assistance to the Palestinian people Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted in compliance with General Assembly resolution 66/118, contains an assessment of the assistance received by the Palestinian people, needs still unmet and proposals for responding to them. This report describes efforts made by the United Nations, in cooperation with the Palestinian Authority, donors and civil society, to support the Palestinian population and institutions. The reporting period is from May 2011 to April 2012. During that period the Palestinian Authority completed its two-year State-building programme. The United Nations enhanced its support to those efforts through its Medium-Term Response Plan. The United Nations is currently executing $1.2 billion of works under that plan and is seeking an additional $1.7 billion for planned works. This complements the humanitarian programming outlined in the 2012 Consolidated Appeal of $416.7 million, of which 38 per cent has been funded as of April 2012. * A/67/50. -

Annual Report #4

Fellow engineers Annual Report #4 Program Name: Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country: West Bank & Gaza Donor: USAID Award Number: 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Reporting Period: October 1, 2013 - September 30, 2014 Submitted To: Tony Rantissi / AOR / USAID West Bank & Gaza Submitted By: Lana Abu Hijleh / Country Director/ Program Director / LGI 1 Program Information Name of Project1 Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country and regions West Bank & Gaza Donor USAID Award number/symbol 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Start and end date of project September 30, 2010 – September 30, 2015 Total estimated federal funding $100,000,000 Contact in Country Lana Abu Hijleh, Country Director/ Program Director VIP 3 Building, Al-Balou’, Al-Bireh +972 (0)2 241-3616 [email protected] Contact in U.S. Barbara Habib, Program Manager 8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800, Silver Spring, MD USA +1 301 587-4700 [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations …………………………………….………… 4 Program Description………………………………………………………… 5 Executive Summary…………………………………………………..…...... 7 Emergency Humanitarian Aid to Gaza……………………………………. 17 Implementation Activities by Program Objective & Expected Results 19 Objective 1 …………………………………………………………………… 24 Objective 2 ……………………................................................................ 42 Mainstreaming Green Elements in LGI Infrastructure Projects…………. 46 Objective 3…………………………………………………........................... 56 Impact & Sustainability for Infrastructure and Governance ……............ -

Timeline – Israel's 20Th Knesset

Timeline – Israel’s 20th Knesset The Reality in Occupied Palestine VS. International Actions (Examples) April 2015 – March 2019 During the campaigning for upcoming Israeli elections, no mainstream candidate has called for a comprehensive peace agreement with Palestine. In fact, the main candidates have campaigned on the preservation and expansion of Israeli settlements, a commitment to further annexation of Palestinian land, reaffirmation of Jerusalem as the exclusive capital of Israel, the dehumanization of Palestinians and the denial of their rights. These candidates, whether from the current government or the opposition, rely upon the perpetuation of the culture of impunity allowing Israel to act without consequence. Indeed, despite the fact that Israel has systematically violated international law and UN resolutions, rather than being threatened or served with sanctions, Israel receives growing international support. With the exception of the approval of UNSC Resolution 2334 in 2016, which condemned the settlement enterprise and affirmed its illegality, no major international measures to hold Israel accountable for its systematic violations and crimes have been implemented during the time period covered. Although it is important to note the responsible resolutions by both the parliaments of Ireland and Chile which voted to ban products produced in illegal Israeli settlements from entering their respective markets. While not comprehensive, or in any way inclusive of Israeli violations, this report highlights some examples of Israeli -

1 Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1

Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1 1 2 Annexe 1 Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1 3 4 Annexe 1 Palestine,ÊLandÊof ÊOlivesÊandÊVinesÊCultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir World Heritage Site Nomination Document Annexes Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage Palestine 2013 Annexe 1 5 6 Annexe 1 Palestine,ÊLandÊof ÊOlivesÊandÊVinesÊCultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Table of Annexes Annex 1 7 Charter on the Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Palestine (The Palestine Charter) Annex 2 19 Declaration regarding the Safeguarding of Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annex 3 27 Guidelines of the Management Plan Annex 4 45 Summary of Battir Case at the Israeli Higher Court Annex 5 51 CULTURAL LANDSCAPE IN PALESTINE Battir Region as a Case Study Annex 6 59 Annex to the Comparative Study Annex 7 67 Maps prepared for Battir Landscape Conservation and Management Plan Project Annexe 1 7 8 Annexe 1 Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1 Charter on the Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Palestine (The Palestine Charter) Annexe 1 9 10 Annexe 1 Palestine,ÊLandÊof ÊOlivesÊandÊVinesÊCultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Preamble: Throughout millennia, Palestine has been a meeting place for civilisations and a cultural bridge between East and West. It has played a pivotal role in the evolution of human history, as attested by evidence of the existence of successive cultures throughout its land, from prehistory onwards. -

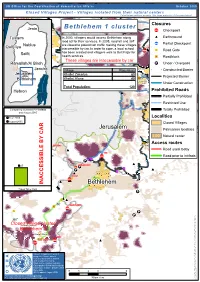

Bethlehem 1 Cluster

º¹DP UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 Qalandiya Camp Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated fromÇ theirQalandiya natural centers º¹ ¬Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) village cluster Beit Duqqu P 144 Atarot ### ¬Ç usalem 3 170 Al Judeira Al Jib Closures ## Bir Nabala Beit 'Anan Jenin BethlehemAl Jib 1 cluster Ç Beit Ijza Closed village cluster ¬ Checkpoint ## ## AL Ram CP ## m al Lahim In 2000, villagers would access Bethlehem Ç#along# Earthmound Tulkarm Jerusalem 2 #¬# Al Qubeiba road 60 for their services. In 2005, road 60 and 367 Ç Qatanna Biddu 150 ¬ Partial Checkpoint Nablus 151 are closed to palestinian traffic making these villages Qalqiliya /" # Hizmah CP D inaccessible by car.ramot In ordercp Beit# Hanina to cope,# al#### Balad a local school Ç # ### ¬Ç D Road Gate Salfit has been created¬ and villagers walk to Beit Fajar for Beit Surik health services. /" Roadblock These villages are inaccessible by car Ramallah/Al Bireh Beit Surik º¹P Under / Overpass 152## Ç##Shu'fat Camp 'Anata Jericho Village Population¬ Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Khallet Zakariya 80 173 Projected Barrier Bethlehem Khallet Afana 40 /" Al 'Isawiya /" Under Construction Total Population: 120 Az Za'ayyemProhibited Roads Hebron ## º¹AzP Za'ayyem Zayem CP ¬Ç 174 Partially Prohibited Restricted Use Al 'Eizariya Comparing situations Pre-Intifada /" Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Closed village cluster Year 2000 Localities Abu Dis Jerusalem 1 August 2005 Closed Villages 'Arab al Jahalin -

Battir Village Profile

Battir Village Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation Azahar Program 2010 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project through the Azahar Program. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Background This booklet is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in Bethlehem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Bethlehem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) and the Azahar Program. The "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Bethlehem Governorate with particular focus on the Azahar program objectives and activities concerning water, environment, and agriculture. -

Profiles of Peace

Profiles of Peace Forty short biographies of Israeli and Palestinian peace builders who have struggled to end the occupation and build a just future for both Palestinians and Israelis. Haidar Abdel Shafi Palestinian with a long history of working to improve the health and social conditions of Palestinians and the creation of a Palestinian state. Among his many accomplishments, Dr. Abdel Shafi has been the director of the Red Crescent Society of Gaza, was Chairman of the first Palestinian Council in Gaza, and took part in the Madrid Peace Talks in 1991. Dr. Haidar Abdel Shafi is one of the most revered persons in Palestine, whose long life has been devoted to the health and social conditions of his people and to their aspirations for a national state. Born in Gaza in 1919, he has spent most of his life there, except for study in Lebanon and the United States. He has been the director of the Red Crescent Society in Gaza and has served as Commissioner General of the Palestinian Independent Commission for Citizens Rights. His passion for an independent state of Palestine is matched by his dedication to achieve unity among all segments of the Palestinian community. Although Gaza is overwhelmingly religiously observant, he has won and kept the respect and loyalty of the people even though he himself is secular. Though nonparti- san he has often been associated with the Palestinian left, especially with the Palestinian Peoples Party (formerly the Palestinian Communist Party). A mark of his popularity is his service as Chairman of the first Palestinian Council in Gaza (1962-64) and his place on the Executive Committee of “There is no problem of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) (1964-65). -

A Case of Israeli “Democratic Colonialism”31

73 “The Frontier is where the Jews Live”: A Case of Israeli “Democratic Colonialism”31 Nicola Perugini32 The frontier is where Jews live, not where there is a line on the map. Golda Meir Space and law, or rather the space of law and law applied to space were among the primary elements of Israeli colonial sovereignty in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) and of the forms of subjugation it employs to express this force. Through colonial practices that have systematically violated the borders of the very same international legislation that enabled ‘temporary’ Israeli occupation, and through the legal regularization of these violations, the landscape of the OPT has been gradually transformed into a legal arena in which colonial sovereignty works by means of a mixed system involving the application –and mutual integration– of increasingly complex laws and constant ‘innovations’ in government instruments and practices affecting Palestinian movements and areas. This historical process has become even more evident after the Oslo Accords, when the institutionalization of the separation between Israelis and Palestinians –without decolonization33– resulted in increased Israeli compartmentalization of the Palestinian landscape and the refinement of its techniques in doing so. Like other colonized peoples, the Palestinians do not live so much in a real system of “suspended sovereignty” (Kimmerling 1982: 200) as in a situation where Israeli colonial sovereignty is continuously undergoing refinement, in a spatial and peripheral frontier in which the colonial encounter (Evans 2009) is the moment of the creation, application and re-activation of the colonial order. In such a context, what is interesting is not so much the question of the legality or illegality of the practices and rules that reify the occupation so much as that of their logic and of how they came into being through space. -

Gaza Strip West Bank

Afula MAP 3: Land Swap Option 3 Zububa Umm Rummana Al-Fahm Mt. Gilboa Land Swap: Israeli to Palestinian At-Tayba Silat Al-Harithiya Al Jalama Anin Arrana Beit Shean Land Swap: Palestinian to Israeli Faqqu’a Al-Yamun Umm Hinanit Kafr Dan Israeli settlements Shaked Al-Qutuf Barta’a Rechan Al-Araqa Ash-Sharqiya Jenin Jalbun Deir Abu Da’if Palestinian communities Birqin 6 Ya’bad Kufeirit East Jerusalem Qaffin Al-Mughayyir A Chermesh Mevo No Man’s Land Nazlat Isa Dotan Qabatiya Baqa Arraba Ash-Sharqiya 1967 Green Line Raba Misiliya Az-Zababida Zeita Seida Fahma Kafr Ra’i Illar Mechola Barrier completed Attil Ajja Sanur Aqqaba Shadmot Barrier under construction B Deir Meithalun Mechola Al-Ghusun Tayasir Al-Judeida Bal’a Siris Israeli tunnel/Palestinian Jaba Tubas Nur Shams Silat overland route Camp Adh-Dhahr Al-Fandaqumiya Dhinnaba Anabta Bizzariya Tulkarem Burqa El-Far’a Kafr Yasid Camp Highway al-Labad Beit Imrin Far’un Avne Enav Ramin Wadi Al-Far’a Tammun Chefetz Primary road Sabastiya Talluza Beit Lid Shavei Shomron Al-Badhan Tayibe Asira Chemdat Deir Sharaf Roi Sources: See copyright page. Ash-Shamaliya Bekaot Salit Beit Iba Elon Moreh Tire Ein Beit El-Ma Azmut Kafr Camp Kafr Qaddum Deir Al-Hatab Jammal Kedumim Nablus Jit Sarra Askar Salim Camp Chamra Hajja Tell Balata Tzufim Jayyus Bracha Camp Beit Dajan Immatin Kafr Qallil Rujeib 2 Burin Qalqiliya Jinsafut Asira Al Qibliya Beit Furik Argaman Alfe Azzun Karne Shomron Yitzhar Itamar Mechora Menashe Awarta Habla Maale Shomron Immanuel Urif Al-Jiftlik Nofim Kafr Thulth Huwwara 3 Yakir Einabus