A Case of Israeli “Democratic Colonialism”31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

Documentation German Palestinian Municipal Partnership Workshop

Documentation German Palestinian Municipal Partnership Workshop Ramallah and Bethlehem 23 November 2014 Imprint Published by: ENGAGEMENT GLOBAL gGmbH – Service für Entwicklungsinitiativen (GLOBAL CIVIC ENGAGEMENT – Service for Development Initiatives) Tulpenfeld 7, 53111 Bonn, Germany Phone +49 228 20 717-0 Ӏ Fax +49 228 20 717-150 [email protected]; www.engagement-global.de Service Agency Communities in the One World [email protected]; www.service-eine-welt.de Text: Petra Schöning Responsible for content: Service Agency Communities in One World, Dr. Stefan Wilhelmy Special thanks go to Mr. Ulrich Nitschke and the GIZ Programmes “Local Governance and Civil Society Development Programme” and “Future for Palestine” for their enormous support in the organization and realization of this workshop. 1 Table of Contents Workshop Schedule ................................................................................................................................. 3 I Objectives .............................................................................................................................................. 4 II Opening Remarks GIZ and Service Agency Communities in One World .............................................. 4 Introduction of GIZ Programmes “Local Governance and Civil Society Development Programme (LGP)” and “Future for Palestine (FfP)” by Ulrich Nitschke (GIZ) ........................................................ 4 Introduction of the Engagement Global Programme “Service Agency Communities in One -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Israeli Proposal in the Jerusalem Metropolitan Area

Israeli Proposal in the Jerusalem Metropolitan Area Deir 'Ibzi Al Ain Ramallah Bireh Deir Arik Dibwan PSAGOT Burqa Beituniya Beit Ur Al Amari RC Foqa MIGRON BET HORON OFER KOCHAV MA'ALE Rafat Kafr YA'ACOV MIKHMAS Tira Aqab Mikhmas 443 Ql.R.C. GIV'AT Qalandia ZE'EV RAMA Judeira ATAROT Jaba Beit GIV'ON Duqqu Ram Beit HDSHA. Al GEVA Inan Beit Jib Bir BINYAMIN Ijza Jib Nabala Abu Qubeiba West Lahm N.YA'ACOV Biddu Nabi Beit Qatanna Samwil Hanina Hizma BH ALON Balad HARADAR ALMON Beit Beit P.ZE'EV KFAR Surik Iksa Shuafat RAMOT ANATOT ADUMIM 1 R.SHLOMO R.C. Anata FR.HILL R.ESHKOL MISHOR 1 'Isawiya ADUMIM Sh. Jarrah Za'im MA'ALE Wadi Joz 1 ADUMIM Tur OLD CITY Azarya W e s t ESilwan a s t Ras al Amud Thuri Abu J e r u s a l e m Dis J.Mukabir Ar.Jahalin NOF Sawahra QEDAR Beit ZION West East Safafa EAST TALPIOT Sharafat Um Leisun Sh. Sur GILO Sa'ad Walaja Baher HAR HAR GILO 60 HOMA Wadi Hummus Battir An Ubaydiya Numan Al Husan Beit Khas JalaBethlehem Kh.Juhzum Wadi Fukin Um Beit Qassis Khadr Sahur Dheisha Al Hindaza Um RC BETAR Ras Shawawra Nahhalin NEVE Rukba Irtas al Wad DANIYEL GEVA'OT Rafidia 374 Beit Za'atara 60 Bad Ta'amir ROSH EFRATA Faluh TZURIM ELAZAR W.Rahhal Abu BAT Kht. Sakarya Nujeim AYIN ALLON Harmala SHVUT W. an Nis KFAR Jurat ELDAD ash Shama KFAR TEKOA ETZION MIGDAL Tuqu' OZ Um NOKDIM Safa Salamuna 0 5 KM Beit Beit Ummar Fajjar 1967 Boundary (“Green Line”) Israeli settler / Bypass road Israeli proposal: West Bank area Israeli-proposed “alternative” to be annexed by Israel Palestinian built-up area Palestinian road link Projection of Israeli proposal Israeli settlement to be Israeli built underpass for in Israeli defined East Jerusalem evacuated Palestinians. -

General Assembly Economic and Social Council

United Nations A/67/84–E/2012/68 General Assembly Distr.: General 8 May 2012 Economic and Social Council Original: English General Assembly Economic and Social Council Sixty-seventh session Substantive session of 2012 Item 71 (b) of the preliminary list* New York, 2-27 July 2012 Strengthening of the coordination of humanitarian and Item 9 of the provisional agenda** disaster relief assistance of the United Nations, including Implementation of the Declaration on the special economic assistance Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples by the specialized agencies and the international institutions associated with the United Nations Assistance to the Palestinian people Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted in compliance with General Assembly resolution 66/118, contains an assessment of the assistance received by the Palestinian people, needs still unmet and proposals for responding to them. This report describes efforts made by the United Nations, in cooperation with the Palestinian Authority, donors and civil society, to support the Palestinian population and institutions. The reporting period is from May 2011 to April 2012. During that period the Palestinian Authority completed its two-year State-building programme. The United Nations enhanced its support to those efforts through its Medium-Term Response Plan. The United Nations is currently executing $1.2 billion of works under that plan and is seeking an additional $1.7 billion for planned works. This complements the humanitarian programming outlined in the 2012 Consolidated Appeal of $416.7 million, of which 38 per cent has been funded as of April 2012. * A/67/50. -

The Springs of Gush Etzion Nature Reserve Nachal

What are Aqueducts? by the Dagan Hill through a shaft tunnel some 400 meters long. In addition to the two can see parts of the “Arub Aqueduct”, the ancient monastery of Dir al Banat (Daughters’ settlement was destroyed during the Bar Kochba revolt. The large winepress tells of around. The spring was renovated in memory of Yitzhak Weinstock, a resident of WATER OF GUSH ETZION From the very beginning, Jerusalem’s existence hinged on its ability to provide water aqueducts coming from the south, Solomon’s pools received rainwater that had been Monastery) located near the altered streambed, and reach the ancient dam at the foot THE SPRINGS OF GUSH ETZION settlement here during Byzantine times. After visiting Hirbat Hillel, continue on the path Alon Shvut, murdered on the eve of his induction into the IDF in 1993. After visiting from which you \turned right, and a few meters later turn right again, leading to the Ein Sejma, descend to the path below and turn left until reaching Dubak’s pool. Built A hike along the aqueducts in the "Pirim" (Shafts) for its residents. Indeed, during the Middle Canaanite period (17th century BCE), when gathered in the nearby valley as well as the water from four springs running at the sides of the British dam. On top of the British dam is a road climbing from the valley eastwards Start: Bat Ayin Israel Trail maps: Map #9 perimeter road around the community of Bat Ayin. Some 200 meters ahead is the Ein in memory of Dov (Dubak) Weinstock (Yitzhak’s father) Dubak was one of the first Jerusalem first became a city, its rulers had to contend with this problem. -

1 Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1

Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1 1 2 Annexe 1 Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1 3 4 Annexe 1 Palestine,ÊLandÊof ÊOlivesÊandÊVinesÊCultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir World Heritage Site Nomination Document Annexes Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage Palestine 2013 Annexe 1 5 6 Annexe 1 Palestine,ÊLandÊof ÊOlivesÊandÊVinesÊCultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Table of Annexes Annex 1 7 Charter on the Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Palestine (The Palestine Charter) Annex 2 19 Declaration regarding the Safeguarding of Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annex 3 27 Guidelines of the Management Plan Annex 4 45 Summary of Battir Case at the Israeli Higher Court Annex 5 51 CULTURAL LANDSCAPE IN PALESTINE Battir Region as a Case Study Annex 6 59 Annex to the Comparative Study Annex 7 67 Maps prepared for Battir Landscape Conservation and Management Plan Project Annexe 1 7 8 Annexe 1 Palestine, Land of Olives and Vines Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Annexe 1 Charter on the Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Palestine (The Palestine Charter) Annexe 1 9 10 Annexe 1 Palestine,ÊLandÊof ÊOlivesÊandÊVinesÊCultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir Preamble: Throughout millennia, Palestine has been a meeting place for civilisations and a cultural bridge between East and West. It has played a pivotal role in the evolution of human history, as attested by evidence of the existence of successive cultures throughout its land, from prehistory onwards. -

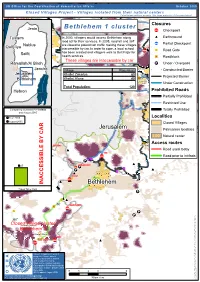

Bethlehem 1 Cluster

º¹DP UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 Qalandiya Camp Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated fromÇ theirQalandiya natural centers º¹ ¬Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) village cluster Beit Duqqu P 144 Atarot ### ¬Ç usalem 3 170 Al Judeira Al Jib Closures ## Bir Nabala Beit 'Anan Jenin BethlehemAl Jib 1 cluster Ç Beit Ijza Closed village cluster ¬ Checkpoint ## ## AL Ram CP ## m al Lahim In 2000, villagers would access Bethlehem Ç#along# Earthmound Tulkarm Jerusalem 2 #¬# Al Qubeiba road 60 for their services. In 2005, road 60 and 367 Ç Qatanna Biddu 150 ¬ Partial Checkpoint Nablus 151 are closed to palestinian traffic making these villages Qalqiliya /" # Hizmah CP D inaccessible by car.ramot In ordercp Beit# Hanina to cope,# al#### Balad a local school Ç # ### ¬Ç D Road Gate Salfit has been created¬ and villagers walk to Beit Fajar for Beit Surik health services. /" Roadblock These villages are inaccessible by car Ramallah/Al Bireh Beit Surik º¹P Under / Overpass 152## Ç##Shu'fat Camp 'Anata Jericho Village Population¬ Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Khallet Zakariya 80 173 Projected Barrier Bethlehem Khallet Afana 40 /" Al 'Isawiya /" Under Construction Total Population: 120 Az Za'ayyemProhibited Roads Hebron ## º¹AzP Za'ayyem Zayem CP ¬Ç 174 Partially Prohibited Restricted Use Al 'Eizariya Comparing situations Pre-Intifada /" Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Closed village cluster Year 2000 Localities Abu Dis Jerusalem 1 August 2005 Closed Villages 'Arab al Jahalin -

Battir Village Profile

Battir Village Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation Azahar Program 2010 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project through the Azahar Program. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Background This booklet is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in Bethlehem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Bethlehem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) and the Azahar Program. The "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Bethlehem Governorate with particular focus on the Azahar program objectives and activities concerning water, environment, and agriculture. -

Metropolitan Jerusalem - August 2006

Metropolitan Jerusalem - August 2006 Jalazun OFRA BET TALMON EL . RIMMONIM 60 Rd Bil'in Surda n llo Beitin Rammun A DOLEV Ramallah Deir Deir Ain DCO Dibwan Ibzi Al Chpt. Arik Ramallah Bireh G.ASSAF Beit Ur 80 Thta. Beituniya Burka 443 Beit Ur PSAGOT Fqa. MIGRON MA'ALE KOCHAV MIKHMAS BET YA'ACOV HORON Kufr Aqab Tira Rafat Mukhmas GIV'AT Kalandiya Beit Chpt. Liqya ZE'EV Beit Jaba GEVA Dukku BINYAMIN Jib Bir Ram Beit Nabala Inan Beit Ijza G.HAHADASHA B. N.YA'ACOV Qubeibe Hanina ALMON/ Bld. Beit Hizma ANATOT Biddu N.Samwil Hanina Qatanna Beit 45 HARADAR Beit P.ZE'EV Iksa Shuafat KFAR Surik ADUMIM RAMOT 1 R.SHLOMO Anata 1 FR. E 1 R.ESHKOL HILL Isawiya Zayim WEST East Jerusalem OLD Tur CITY I S R A E L Azarya MA'ALE Silwan ADUMIM Abu Thuri Dis Container Chpt. KEDAR Sawahra EAST Beit TALPIOT Safafa G. Sh.Sa'ad HAMATOS Sur GILO Walaja Bahir HAR HAR Battir GILO HOMA Ubaydiya Numan Mazmuriya Husan B.Jala Chpt. Wadi Al Kh.Juhzum 5 Km Fukin Bethlehem Khas Khadr B.Sahur BETAR ILLIT Um Shawawra NEVE Rukba Irtas Hindaza Nahhalin DANIEL GEVA'OT 60 Jaba ROSH TZURIM Za'atara Kht. EFRATA W.Rahhal BAT ELAZAR AYIN Zakarya Harmala ALLON W.an Nis SHVUT Jurat KFAR ELDAD Surif KFAR ash Shama TEKOA ETZION NOKDIM Tuku' Safa MIGDAL W e s t B a n k Beit OZ Beit Ummar Fajjar Map : © Jan de Jong Palestinian Village, Green Line Main Palestinian City or Road Link Neighborhood Jerusalem Israeli Settlement, Separation Israeli Checkpoint Existing / Barrier and/or Gate Under Construction Trajectory Israeli (Re) Constructed Israeli Civil or Military Israeli Municipal Settler Road, Facility and Area Limit East Jerusalem Projected or Under Construction E 1-Plan Outline Settlement Area Planned Settlement East of the Barrier 60 Road Number Construction . -

NGO MONITOR: SHRINKING SPACE Defaming Human Rights Organizations That Criticize the Israeli Occupation

NGO MONITOR: SHRINKING SPACE Defaming human rights organizations that criticize the Israeli occupation A report by the Policy Working Group September 2018 PWG Policy Working Group Table of content 3 Foreword 6 Executive Summary 11 Chapter 1: Ideological bias and political ties Background Partisan people One-sided focus, intrinsic bias Connections with the Israeli government and state authorities 19 Chapter 2: Lack of financial transparency 23 Chapter 3: Faulty research and questionable ethics Baseless claims and factual inaccuracies Dismissing and distorting thorough research 28 Chapter 4: Foul tactics Framing the occupation as an internal Israeli affair Branding NGOs as an existential threat in order to deflect criticism of the occupation Using BDS to defame Palestinian and Israeli NGOs Accusing Palestinian NGOs of “terrorist affiliations” 40 Notes 2 Foreword NGO Monitor is an organization that was founded in 2002 under the auspices of the conservative think tank JCPA (the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs) and has been an independent entity since 2007. Its declared goal is to promote “transparency and accountability of NGOs claiming human rights agendas, primarily in the context of the Arab-Israeli conflict”.1 This is a disingenuous description. In fact, years of experience show that NGO Monitor’s overarching objective is to defend and sustain government policies that help uphold Israel’s occupation of, and control over, the Palestinian territories. Israeli civil society and human rights organizations consistently refrained from engaging with NGO Monitor. Experience taught that responding to its claims would be interpreted in bad faith, provide ammunition for further attacks and force the targeted organizations to divert scarce resources away from their core mission – promoting human rights and democracy.