Eleutherios Venizelos and the Balkan Wars*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vladimir Paounovsky

THE B ULGARIAN POLICY TTHE BB ULGARIAN PP OLICY ON THE BB ALKAN CCOUNTRIESAND NN ATIONAL MM INORITIES,, 1878-19121878-1912 Vladimir Paounovsky 1.IN THE NAME OF THE NATIONAL IDEAL The period in the history of the Balkan nations known as the “Eastern Crisis of 1875-1879” determined the international political development in the region during the period between the end of 19th century and the end of World War I (1918). That period was both a time of the consolidation of and opposition to Balkan nationalism with the aim of realizing, to a greater or lesser degree, separate national doctrines and ideals. Forced to maneuver in the labyrinth of contradictory interests of the Great Powers on the Balkan Peninsula, the battles among the Balkan countries for superiority of one over the others, led them either to Pyrrhic victories or defeats. This was particularly evident during the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars (The Balkan War and The Interallied War) and World War I, which was ignited by a spark from the Balkans. The San Stefano Peace Treaty of 3 March, 1878 put an end to the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). According to the treaty, an independent Bulgarian state was to be founded within the ethnographic borders defined during the Istanbul Conference of December 1876; that is, within the framework of the Bulgarian Exarchate. According to the treaty the only loss for Bulgaria was the ceding of North Dobroujda to Romania as compensa- tion for the return of Bessarabia to Russia. The Congress of Berlin (June 1878), however, re-consid- ered the Peace Treaty and replaced it with a new one in which San Stefano Bulgaria was parceled out; its greater part was put under Ottoman control again while Serbia was given the regions around Pirot and Vranya as a compensation for the occupation of Novi Pazar sancak (administrative district) by Austro-Hun- - 331 - VLADIMIR P AOUNOVSKY gary. -

Section Iv. Interdisciplinary Studies and Linguistics Удк 821.14

Сетевой научно-практический журнал ТТАУЧНЫЙ 64 СЕРИЯ Вопросы теоретической и прикладной лингвистики РЕЗУЛЬТАТ SECTION IV. INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES AND LINGUISTICS УДК 821.14 PENELOPE DELTA, Malapani A. RECENTLY DISCOVERED WRITER Athina Malapani Teacher of Classical & Modern Greek Philology, PhD student, MA in Classics National & Kapodistrian University of Athens 26 Mesogeion, Korydallos, 18 121 Athens, Greece E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] STRACT he aim of this article is to present a Greek writer, Penelope Delta. This writer has re Tcently come up in the field of the studies of the Greek literature and, although there are neither many translations of her works in foreign languages nor many theses or disser tations, she was chosen for the great interest for her works. Her books have been read by many generations, so she is considered a classical writer of Modern Greek Literature. The way she uses the Greek language, the unique characters of her heroes that make any child or adolescent identified with them, the understood organization of her material are only a few of the main characteristics and advantages of her texts. It is also of high importance the fact that her books can be read by adults, as they can provide human values, such as love, hope, enjoyment of life, the educational significance of playing, the innocence of the infancy, the adventurous adolescence, even the unemployment, the value of work and justice. Thus, the educative importance of her texts was the main reason for writing this article. As for the structure of the article, at first, it presents a brief biography of the writer. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

IX. Nationale Ansprüche, Konflikte Und Entwicklungen in Makedonien

IX. Nationale Ansprüche, Konflikte und Entwicklungen in !akedonien, 1870–1912 Vasilis K. Gounaris 1. Vom bulgarischen Exarchat bis zur bulgarischen Autonomie Kraft des ersten Artikels des Firmans des Sultans vom 27. Februar (nach dem alten Kalender) 1870 wurde ohne Wissen des Patriarchats das bulgarische Exarchat gegründet. Von den 13 Kirchenprovinzen, die in seine Verantwortung übergingen, könnte man nur die Metropolis von Velesa rein formell als makedonisch bezeichnen. Doch gemäß dem zehnten Artikel des Firmans konnten auch andere Metropoleis dem Exarchat beitreten, wenn dies mindestens zwei Drittel ihrer Gemeindemitglieder wünschten. Dieser Firman gilt als die Geburtsurkunde der Makedonischen Frage, was jedoch nicht zutrifft. Die Voraussetzungen für die Entstehung feindlicher Parteien und die Nationalisierung dieser Gegensätze waren Produkt der poli- tischen, sozialen und wirtschaftlichen Umschichtungen, die der Erlass Hatt-i Humayun (Februar 1856) mit sich gebracht hatte. Dieser Erlass hatte zu Veränderungen des Grund- besitzsystems zu Gunsten der Christen geführt und die çifliks offiziell vererblich gemacht. Er hatte auch die Voraussetzungen für öffentliche Arbeiten und für eine Änderung des Steuer- und des Kreditsystems geschaffen. Und schließlich war, im Rahmen der Abfassung von Rechtskodizes, vom Patriarchat die Abfassung allgemeiner Verordnungen für die Verwaltung der Orthodoxen unter Mitwirkung von Laien verlangt worden. Die Fertigstellung und die Anwendung der Verordnungen führte nacheinander – schon in den Sechzigerjahren -

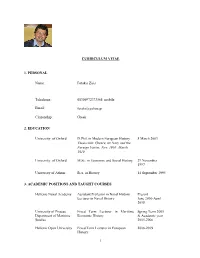

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE 1. PERSONAL Name: Fotakis Zisis Telephone : 00306972373568 mobile Email: [email protected] Citizenship: Greek 2. EDUCATION University of Oxford D.Phil. in Modern European History 8 March 2003 Thesis title: Greece, its Navy and the Foreign Factor, Nov. 1910- March 1919 University of Oxford M.Sc. in Economic and Social History 29 November 1997 University of Athens B.A. in History 14 September 1995 3. ACADEMIC POSITIONS AND TAUGHT COURSES Hellenic Naval Academy Assistant Professor in Naval History Present Lecturer in Naval History June 2010-April 2018 University of Piraeus Fixed Term Lecturer in Maritime Spring Term 2005 Department of Maritime Economic History & Academic year Studies 2005-2006 Hellenic Open University Fixed Term Lecturer in European 2006-2019 History 1 University of the Aegean, Fixed Term Lecturer in History Fall Term 2004 Department of Educational Studies The Hellenic Military Instructor in Political History Spring 2005 Petty Officer College The Hellenic Joint Forces Instructor in Strategy and the History Academic Years Academy and the of War 2010-2011 Supreme National War 2012-2013 College 2014-2015 The Hellenic Naval War Instructor in Naval History Academic Years College 2004-2010, 2012-2013, 2015-2016 The Hellenic Naval Petty Instructor in Naval History Academic Years Officers College 2003-2007, 2008-2009 Panteion University of Instructor in Strategic Analysis 2014-2018 Social Sciences 4. OTHER PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & ACTIVITIES International Commission Member of the Committee 2010-present of Military History- Bibliography Committee Mediterranean Maritime Member October 2008 - History Network present Hellenic Commission on Member of the Board August 2008 - Military History August 2021 Nuffield Foundation Research assistant to Foreman-Peck, 1998-1999 J., & Pepelasis Minoglou, I., “Entrepreneurship and Convergence. -

1 Russian Policy in the Balkans, 1878-1914

1 Russian Policy in the Balkans, 1878-1914 At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the Balkans were the most turbulent region in Europe. On the one hand were the Balkan peoples with their aims of creating their own national states with the broadest borders possible, and on the other, the ambitions of the Great Powers to gain spheres of influence in the European territories of the Ottoman Empire. This led to a continually strained and unstable situation. 1.1 Between the Two Wars: 1856-1877 The Crimean War proved to be the turning point in the relations between Russia and the Near East. After this first serious defeat of the Russian army in a war with the Ottoman Empire, Christians of the Near East and the Balkans looked more and more towards Europe. The image of Russia as the liberator of the Orthodox inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire faded and the authority of the Russian tsar was to a great extent lost. Russian diplomacy after 1856 focused totally on the restoration of Russia’s former authority. Of great significance in this process were the activities of Count N. P. Ignatiev, the ambassa- dor to Constantinople from 1864 to 1877.11 His idea of creating ‘Greater Bulgaria’, a large south-Slavonic state in the Balkans, as a base for Russian interests and further penetra- tion towards the Straits, received the support of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and coincided with the intentions of Tsar Alexander II. In 1870, the Russian government declared that it would no longer comply with the restrictions of the Paris Treaty of 1856. -

Balkan Wars and the Albanian Issue

QAFLESHI, MUHARREM, AJHC, 2018; 1:8 Review Article AJHC 2018,1:8 American Journal of History and Culture (ISSN:2637-4919) Balkan Wars and the Albanian issue QAFLESHI, MUHARREM , Mr. Sc. Phd (c) PRISHTINA UNIVERSITY, DEPARTAMENT OF HISTORY Albanian Address: Street “Bil Clinton” nr. n.n. 22060 Bellobrad -Kosovo ABSTRACT This paper will elaborate the collapse of the Turkish rule in the *Correspondence to Author: Balkans and the future fate of Albania, embarking on the new QAFLESHI, MUHARREM plans of the invasive politics of the Balkan Alliance, especially PRISHTINA UNIVERSITY, DEPAR- of Serbia, Montenegro and Greece. Then the dramatic events TAMENT OF HISTORY Albanian during the Balkan Wars 1912-1913, the occupation of Kosovo Address: Street “Bil Clinton” nr. n.n. and other Albanian lands by Serbia, the Albanian resistance with 22060 Bellobrad -Kosovo special focus on Luma, Opoja and Gora. It will also discuss the rapid developments of the Balkan Wars, which accelerated the Declaration of the Independence of Albania on 28 November, How to cite this article: 1912, and organization of the Ambassadors Conference in Lon- QAFLESHI, MUHARREM.Bal- don, which decided to recognize the Autonomy of Albania with kan Wars and the Albanian issue. today’s borders. Then, information about the inhumane crimes of American Journal of History and the Serbian Army against the Albanian freedom-loving people, Culture, 2018,1:8. committing unprecedented crimes against the civilian population, is given. Keywords: Serbia, Montenegro, Ottoman Empire, Gora, Opoja, eSciPub LLC, Houston, TX USA. Luma. For ProofWebsite: Only http://escipub.com/ AJHC: http://escipub.com/american-journal-of-history-and-culture/ 0001 QAFLESHI, MUHARREM, AJHC, 2018; 1:8 Collapse of the Ottoman Empire and interested as other Balkan oppressed people to creation of the Balkan Alliance become liberated from the Ottoman yoke. -

Balkan Wars Between the Lines: Violence and Civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918

ABSTRACT Title of Document: BALKAN WARS BETWEEN THE LINES: VIOLENCE AND CIVILIANS IN MACEDONIA, 1912-1918 Stefan Sotiris Papaioannou, Ph.D., 2012 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe, Department of History This dissertation challenges the widely held view that there is something morbidly distinctive about violence in the Balkans. It subjects this notion to scrutiny by examining how inhabitants of the embattled region of Macedonia endured a particularly violent set of events: the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War. Making use of a variety of sources including archives located in the three countries that today share the region of Macedonia, the study reveals that members of this majority-Orthodox Christian civilian population were not inclined to perpetrate wartime violence against one another. Though they often identified with rival national camps, inhabitants of Macedonia were typically willing neither to kill their neighbors nor to die over those differences. They preferred to pursue priorities they considered more important, including economic advancement, education, and security of their properties, all of which were likely to be undermined by internecine violence. National armies from Balkan countries then adjacent to geographic Macedonia (Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia) and their associated paramilitary forces were instead the perpetrators of violence against civilians. In these violent activities they were joined by armies from Western and Central Europe during the First World War. Contrary to existing military and diplomatic histories that emphasize continuities between the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War, this primarily social history reveals that the nature of abuses committed against civilians changed rapidly during this six-year period. -

Three Images of the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 Enika Abazi

Between Facts and Interpretations: Three Images of the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 Enika Abazi To cite this version: Enika Abazi. Between Facts and Interpretations: Three Images of the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. James Pettifer; Tom Buchanan. War in the Balkans: Conflict and Diplomacy before World War I, I.B.Tauris, pp.203-225, 2016, 978-1-78453-190-4. halshs-01252639 HAL Id: halshs-01252639 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01252639 Submitted on 11 Jan 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. z z-ce: ~ ~ ~ u w ~ C';j ~ ,.,,1,---'4 ~z 0 •J.:\ • 1-l ..-,'1111 0 Lq 1:-:i 1 ! 1 ·i l1l WARIN THE BALKANS Edited by JAMES PETTIFER Conflict and Diplomacy before World War I AND TOM BUCHANAN a The history of the Balkans incorporates ali the major historical themes of the twentieth century- the rise of nationalism, communism and fascism, state-sponsored genocide and urban warfare. Focusing on the century's opening decades, T+ar in the Balkans seeks to shed new light on the Balkan Wars through approaching each regional and ethnie conflict as a separate actor, before placing them in a wider context. -

Die Entwicklung Griechenlands Und Die Deutsch-Griechischen Beziehungen Im 19

Südosteuropa - Studien ∙ Band 46 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Bernhard Hänsel (Hrsg.) Die Entwicklung Griechenlands und die deutsch-griechischen Beziehungen im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Bernhard Hänsel - 978-3-95479-690-8 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 09:42:23AM via free access 00055622 SUDO STEUROPA-STUDIEN herausgegeben im Auftrag der Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft von Walter Althammer Bernhard Hänsel - 978-3-95479-690-8 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 09:42:23AM via free access Die Entwicklung Griechenlands und die deutsch-griechischen Beziehungen im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert herausgegeben von Bernhard Hansel Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft München 1990 Bernhard Hänsel - 978-3-95479-690-8 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 09:42:23AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München CIP-Titelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Entwicklung Griechenlands und die deutsch-griechischen Beziehungen im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert/ Südosteuropa-Ges. ,.München : Südosteuropa-Ges ־ .Hrsg. von Bernhard Hansel 1990 (Südosteuropa-Studien -

Introduction: the Wars of Yesterday: the Balkan Wars and The

The Wars of Yesterday The Balkan Wars and the Emergence of Modern Military Conflict, 1912/13 An Introduction Katrin Boeckh and Sabine Rutar The Balkan Wars of 1912/13 and their outcomes have shaped much of the military and political thinking of the Balkan elites during the last century. At the same time, these wars were intimations of what was to become the bloodiest, most violent century in Europe’s and indeed humankind’s history. Wars often lead to other wars. Yet this process of contagion happened in a particularly gruesome manner during the twentieth century. In Europe, the Balkan Wars marked the beginning of the twentieth century’s history of warfare. In the First Balkan War (October 1912–May 1913), Serbia, Monte- negro, Greece and Bulgaria declared war on the Ottoman Empire; in the Second Balkan War (June–August 1913), Bulgaria fought Serbia, Montenegro and Greece over the Ottoman territories they had each just gained. From July onwards, Serbia, Montenegro and Greece were supported by Romania, who entered the war hoping to seize the southern Dobruja from Bulgaria. These hopes were realized. Albania, declared an independent state in November 1912, was thus a product of the First Balkan War. The borders of other territories were changed and obtained features that partially remain valid up to the present: the historical region of Macedonia, a main theatre of the wars, was divided among Greece (Aegean Macedonia), Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia) and Serbia (Vardar Macedonia, corresponding largely to today’s Republic of Macedonia, established in 1991). The Ottoman Empire’s loss of most of its European territories in the conflict was one more warning sign of its inner weakness; it ceased to exist in the aftermath of the First World War, and was succeeded by the Republic of Turkey in 1923. -

The Balkan War and Its Implications for Islamic Socio-Political Life in Southeast Europe (1876-1914 AD)

International Journal of Science and Society, Volume 2, Issue 4, 2020 The Balkan War and Its Implications for Islamic Socio-Political Life in Southeast Europe (1876-1914 AD) Kemal Pasha Centre of Mustafa Kemal Ankara, Turkey Email: [email protected] Abstract This research describes the historical series of the occurrence of the Balkan Wars and the implications thereof for Muslim life there. This study took three main problems, namely (1) the causes of the Balkan Wars, (2) the chronology of the Balkan wars, and (3) What are the implications of the Balkan wars on the socio-political life of Islam in Southeast Europe. The research method used in this thesis is the historical research method. 4 stages, namely (1) Heuristics, (2) Source/Verification Criticism, (3) Interpretation and (4) Historiography. There are two approaches used in this study, namely the political and sociological approaches. While the theory I use in this research is theory. Conflict and social change theory. The results of the research that the authors obtained are: chronologically, the Balkan war was preceded by the problem of Macedonia which in the end was used as an excuse to legitimize the war. Basically, the main cause of this Balkan war was due to the ambition and personal grudge between the respective rulers of the Balkan countries and the Ottoman Empire. It was also driven by the decline of the sultanate, Russian domination, the Turkish-Italian war (1911-1912), the idea of nationalism, propaganda, the formation of the Balkan alliance and the failure of diplomacy. The outbreak of the Balkan war not only resulted in geo-political changes but also was a humanitarian catastrophe for Muslims in the Balkans who at that time had to accept the fact that their situation was no longer the same as when it was led by Muslims because authority had shifted to non-Muslims.