Voces Intimae String Quartets 1890 -1922 Tempera Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover the World of Linn Records

CKD 220 ALSO AVAILABLE FROM LINN RECORDS BY SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA FELIX MENDELSSOHN WOLFGANG AMADEUS JOHANNES BRAHMS Violin Concerto MOZART Violin Concerto Symphony No.3 ‘Scottish’ Requiem Hungarian Dances Hebrides Overture Adagio & Fugue – CKD 224 (SACD) – – CKD 216 (SACD) – – CKD 211 (SACD) – @ www.linnrecords.com discover the world of linn records Linn Records, Glasgow Road, Waterfoot, Glasgow G76 0EQ, UK t: +44 (0)141 303 5027/29 f: +44 (0)141 303 5007 e: [email protected] a soaring but seemingly unattainable joy, this mitigated little against the overall Jean Sibelius impression of a relentless underlying force”. [The Guardian, London]. He continues his relationship with the Orchestra, returning regularly over forthcoming seasons. Pelleas and Melisande Swensen is a regular guest conductor with many of the world’s major 1. At the Castle Gate 2. Melisande orchestras, and appearances in recent seasons have included the London 3. At the Seashore 4. A Spring in the Park Philharmonic, BBC Symphony, Hallé, Bournemouth Symphony, City of Birmingham 5. The Three Blind Sisters 6. Pastorale Symphony, Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, Mozarteum, Staatsorchester 7. Melisande at the Spinning-Wheel Stuttgart, Real Orquestra Sinfonica de Sevilla, and, in North America, the Los Angeles 8. Entr’acte 9. The Death of Melisande Philharmonic, Saint Paul Chamber, Saint Louis, Dallas, Indianapolis and Toronto Symphony Orchestras. Kuolema Before deciding to dedicate himself solely to his conducting career, Joseph 10. Valse Triste Swensen enjoyed a highly-successful career as a professional violinist, appearing as a soloist with the world’s major orchestras. Nowadays his occasional appearances as a Belshazzar’s Feast violin soloist are a natural extension of his work as a conductor, playing and directing 11. -

Gräsbeck 2017.5236 Words

Which of Sibelius’s 379 miniatures are remarkable? Folke Gräsbeck "Auch kleine Dinge können uns entzücken…" (Paul Heyse) Reckoning that Sibelius’s compositions amount to circa 600 separate pieces (youth works included, fragments omitted), we have to consider that roughly more than half of them are miniatures. I have calculated that nearly 380 original, separate pieces last less than 4 minutes. If we reject only Sibelius’s miniatures, we omit practically half his production. ‘I am a man of the orchestra᾿, Sibelius proclaimed. Needless to say, his successful orchestral works, generally regarded as national monuments in Finland, are impressive frescos; nonetheless, these large-scale pieces are full of carefully elaborated details. What about the painstakingly worked-out details in his small works? Do they lack credibility because they are included in miniatures? Sibelius ‘forged᾿ the motifs and melodies in the small pieces no less carefully, sometimes referring to his miniatures as his ‘suffering pieces᾿ or 'pain pieces'[1]. Probably he would not have referred to them in this way if he had not valued them highly. The designation ‘salon piece’ is clumsy as applied to Sibelius’s miniatures. Very few of them were purposely composed as standard salon music – they are all too refined and abstract, and lack the lax and redundant reiterations so typical of such pieces. Perhaps the Valse lyrique, Op. 96a, approaches a real salon piece, but the material soars far above standard salon vocabulary, the lyrical sections, for example, revealing remarkable intimacy and character. Nowadays, it is common to employ the designation ‘Salon music’ in a pejorative sense. -

Reviewing Rachmaninov

MUSIC knows it. To hear her is truly heartbreaking, recordings), particularly in the 3rd and REVIEWS and Elgar’s nostalgic concerto is perhaps 5th. It is still unbeatable today, both CH’S HALF DOZEN the perfect vehicle for such a tragic figure. for its electrifying sound and inspired Dame Janet Baker provides stunning vocals performances. Previn’s return to the to another of Elgar’s rarities, the beautiful catalogue with a vengeance is long- song cycle, Sea Pictures. EMI has remastered awaited, especially in this complete edition Rawks this classic with their new technology that’s which includes rare gems such as the Keeping CLASSICAL TIME PIECES TO PASS been proven to deliver a far superior sound delectable Tuba Concerto (a first on CD) THE HOURS WITH to the earlier CD releases, so if you haven’t and the even more obscure Violin Concerto. time yet acquired this historic recording, there’s SERGEI PROKOFIEV: no better time to do so. ZOLTAN KODALY: VIENNESE MUSICAL BY CH LOH ALEXANDER NEVSKY CLOCK (HARY JANOS SUITE) Yuri Temirkanov, St Petersburg One of the most colourful musical HOOKED ON CLASSICS: SIBELIUS, Philharmonic timepieces in classical music, just wind it SEASICKNESS AND MORE (RCA RED SEAL 60867) up and hear it go! SOUL-STIRRING STUFF... Of RCA’s reissues of a bunch of titles Neeme Jarvi, Chicago Symphony Orch from their mid-1990s catalogue, this is (Chandos 8877) perhaps the most exciting. It represents a SERGEI PROKOFIEV: CINDERELLA pioneering effort to present the score of (COMPLETE BALLET) this Eisenstein Stalin pleaser in modern It’s that horrifying twelve-chimer that sent sound – and if you have ever watched the SERGEI RACHMANINOV, PIANO poor Cindy out of the dance floor, minus one black-and-white classic with its disgraceful CONCERTOS 1-4, PAGANINI RHAPSODY glass slipper. -

Yhtenäistetty Jean Sibelius Teosten Yhtenäistettyjen Nimekkeiden Ohjeluettelo

Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja 115 Yhtenäistetty Jean Sibelius Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo Heikki Poroila Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Helsinki 2012 Julkaisija: Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Layout Heikki Poroila Kuva Akseli Gallén-Kallela © Heikki Poroila 2012 Neljäs tarkistettu laitos (verkkoversio 2.2) kesäkuu 2015. Suomen kirjastosäätiö on tukenut tämän verkkojulkaisun valmistamista. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Yhtenäistetty Jean Sibelius : Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo. - Neljäs tarkistettu laitos. – Helsinki : Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys, 2012. – 75 s. : kuv. – (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja, ISSN 0784-0322 ; 115). – ISBN 952- 5363-14-7. ISBN 952-5363-14-7 (PDF) Yhtenäistetty Jean Sibelius 2 Lukijalle Tällä Sibelius-luettelolla on ollut kaksi varhaisempaa paperille painettua olomuotoa. Ensimmäinen versio ilmestyi jo vuonna 1989 tilanteessa, jossa kansallissäveltäjämme tuotannon perusteellinen tutkimus ja kunnollisen teosluettelon valmistaminen oli paradoksaalisesti vasta käynnistynyt. Ohje- luetteloa kootessani tiesin monien asioiden tulevaisuudessa muuttuvan, mutta perusluettelon tarvetta ei voinut kiistää. Kun toinen, korjattu painos vuonna 1996 ilmestyi, ratkaiseva askel tutkimuspuo- lella oli jo otettu. Fabian Dahlström oli saanut teosluettelonsa niin pitkälle, että oli kyennyt nume- roimaan opusnumerottomat teokset JS-koodilla. Tämä oli jo riittävä syy uuden laitoksen valmista- miseen, mutta samalla päästiin korjaamaan lukuisia virheitä ja epäjohdonmukaisia -

SIBELIUS, Johan (Jean) Christian Julius (1865-1957)

BIS-CD-1265 Sib cantatas 7/12/04 10:04 AM Page 2 SIBELIUS, Johan (Jean) Christian Julius (1865-1957) 1 Snöfrid, Op. 29 (1900) (Wilhelm Hansen) 14'15 Improvisation for recitation, mixed chorus and orchestra Text: Viktor Rydberg Allegro molto – Andantino – Melodrama. Pesante – Andante (ma non troppo lento) Stina Ekblad narrator Jubilate Choir (choral direction: Astrid Riska) 2 Overture in A minor for orchestra, JS 144 (1902) (Fazer) 9'13 Andante molto sostenuto – Allegro – Tempo I Cantata for the Coronation of Nicholas II, JS 104 (1896) (Manuscript) 18'37 (Kantaatti ilo- ja onnentoivotusjuhlassa Marraskuun 2. päivänä 1896) for mixed chorus and orchestra Text: Paavo Cajander 3 I. Allegro. Terve nuori ruhtinas… 8'33 4 II. Allegro. Oikeuden varmassa turvassa… 9'58 Jubilate Choir (choral direction: Astrid Riska) 2 BIS-CD-1265 Sib cantatas 7/12/04 10:04 AM Page 3 Rakastava, Op. 14 ( [1894]/1911-12) (Breitkopf & Härtel) 12'18 for string orchestra, timpani and triangle 5 I. The Lover. Andante con moto 4'06 6 II. The Path of His Beloved. Allegretto 2'26 7 III. Good Evening!… Farewell! Andantino – Doppio più lento – Lento assai 5'34 Jaakko Kuusisto violin • Ilkka Pälli cello 8 Oma maa (My Own Land), Op. 92 (1918) (Fazer) 13'26 for mixed chorus and orchestra Text: Kallio (Samuel Gustaf Bergh) Allegro molto moderato – Allegro moderato – Vivace (ma non troppo) – Molto tranquillo – Tranquillo assai – Moderato assai (e poco a poco più largamente) – Largamente assai Jubilate Choir (choral direction: Astrid Riska) 9 Andante festivo, JS 34b (1922/1938) for strings and timpani (Fazer) 5'10 TT: 74'48 Lahti Symphony Orchestra (Sinfonia Lahti) (Leader: Jaakko Kuusisto) Osmo Vänskä conductor 3 BIS-CD-1265 Sib cantatas 7/5/04 10:31 AM Page 4 Snöfrid, Op. -

Winter 2015/2016

N N December 2015 January/February 2016 Volume 44, No. 2 Winter Orgy® Period N 95.3 FM Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition; Reiner, Chicago WHRB Program Guide Symphony Orchestra (RCA) Bach: Violin Concerto No. 1 in a, S. 1041; Schröder, Hogwood, Winter Orgy® Period, December, 2015 Academy of Ancient Music (Oiseau-Lyre) Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue; Katchen, Kertesz, London with highlights for January and February, 2016 Symphony Orchestra (London) Chopin: Waltzes, Op. 64; Alexeev (Seraphim) Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, Op. 35; Staryk, Beecham, Wednesday, December 2 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (EMI) Strauss, J., Jr.: On the Beautiful Blue Danube, Op. 314; Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (DG) 6:45 pm HARVARD MEN’S BASKETBALL Tchaikovsky: Ouverture solennelle, 1812, Op. 49; Bernstein, Harvard at Northeastern. Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (DG) 6:45 pm HARVARD MEN’S HOCKEY Harvard at Union. Thursday, December 3 10:00 pm BRIAN CHIPPENDALE (cont.) 10:00 pm BRIAN CHIPPENDALE Hailing from Providence, Rhode Island, drummer Brian Saturday, December 5 Chippendale has been churning out an endless wall of noise since the late 90s. Using a hand-painted and well-beaten drum 5:00 am PERDIDO EN EL SIGLO: A MANU CHAO kit, homemade masks equipped with contact mics, and an ORGY (cont.) array of effect and synthesizer pedals, his sound is powerful, 9:00 am HILLBILLY AT HARVARD relentless, and intensely unique. Best known for his work with 12:45 pm PRELUDE TO THE MET (time approximate) Brian Gibson as one half of noise-rock duo Lightning Bolt, 1:00 pm METROPOLITAN OPERA Chippendale also works with Matt Brinkman as Mindflayer and Puccini: La Bohème; Barbara Frittoli, Ana Maria solo as Black Pus. -

The Harold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Special Collections Bibliographies University Special Collections 1993 The aH rold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University: A Complete Catalogue (1993) Gisela S. Terrell Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Terrell, Gisela S., "The aH rold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University: A Complete Catalogue (1993)" (1993). Special Collections Bibliographies. Book 1. http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^ IT fui;^ JE^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IViembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/haroldejohnsonjeOOgise The Harold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University A Complete Catalogue Gisela Schliiter Terrell 1993 Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library Butler University Indianapolis, Indiana oo Printed on acid-free paper Produced by Butler University Publications ©1993 Butler University 500 copies printed $15.00 cover charge Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library, Butler University 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46208 317/283-9265 Dedicated to Harold E. Johnson (1915-1985) and Friends of Music Everywhere Harold Edgar Johnson on syntynyt Kew Gardensissa, New Yorkissa vuonna 1915. Hart on opiskellut Comell-yliopistossa (B.A. 1938, M.A. 1939) javaitellyt tohtoriksi Pariisin ylopistossa vuonna 1952. Han on toiminut musiikkikirjaston- hoitajana seka New Yorkin kaupungin kirhastossa etta Kongressin kirjastossa, Oberlin Collegessa seka viimeksi Butler-yliopistossa, jossa han toimii musiikkiopin apulaisprofessorina. -

TMTP Orchestra Comprehensive Listing 2018

Teaching Music through Performance in Orchestra A Comprehensive Listing of All Volumes by Grade, 2018 Volumes 1–3 GIA Publications, Inc. Contents Core Components . 4 Through the Years with the Teaching Music Series . 5 Orchestra, volumes 1–3 . 6 Core Components The Books Part I presents essays by the leading lights of instrumental music education, written specifically for the Teaching Music series to instruct, inform, enlighten, inspire, and encourage music directors in their daily tasks . Part II presents Teacher Resource Guides that provide practical, detailed reference to the best-known and foundational orchestral compositions, Grades 2–6, and their composers . In addition to historical background and analysis, music direc- tors will find insight and practical guidance for streamlining and energizing rehearsals . The Recordings Michigan State University Symphony Orchestra The Symphony Orchestra, established in 1927, presented the gala opening concert of the Music Educators Midwestern Conference in Ann Arbor, Michigan and performed the opening concert in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Midwest International Conference of Bands and Orchestras in Chicago . The Symphony Orchestra has recorded for Koch International Classics, Arizona University Records, GIA Records, and PBS specials . Leon Gregorian Leon Gregorian is Professor of Music, Director of Orchestras, and head of the Graduate Orchestral Conducting Program at the Michigan State University College of Music . He holds degrees from the New England Conservatory of Music and Michigan State University . Gregorian has guest-conducted leading orchestras in Venezuela, Mexico, South Korea, Italy, Rumania, Armenia, Russia, Brazil, Argentina, Czech Republic, Australia, and the People’s Republic of China, as well as many orchestras in the United States . -

Download Booklet

552135-36bk VBO Sibelius 7/8/06 9:17 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Pelléas et Mélisande, Op. 46 Prelude to Act I Scene 1, ‘At the Castle Gate’ . 2:42 2 Kyllikki – 3 Lyric Pieces for piano, Op. 41 Comodo . .. 3:18 3 The Oceanides . 10:18 4 Andante Festivo . 4:27 5 6 Songs, Op. 36 No.4 Reed, reed, rustle . 2:29 6 Valse triste, Op. 44, No.1 . 4:41 7 Symphony No. 5 in E flat, Op. 82 III. Allegro molto . 9:27 8 Romance for strings, Op. 42 . 4:50 9 Pohjola’s Daughter, Op. 49 . 13:58 0 Finlandia . 8:12 Total Timing . 64:45 CD2 1 Karelia Suite I. Intermezzo . 3:51 2 Karelia Suite III. Alla marcia . 4:30 3 Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 II. Adagio di molto . 7:53 4 En Saga, Op. 9 . 17:28 5 6 Songs, Op.17 No. 6 To Evening . 1:33 6 The Tempest – Suite No. 2, Op.109 No. 3 Dance of the Nymphs . .. 1:56 7 Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 III. Scherzo (Allegro) . 5:09 8 Lemminkaïnen Suite, Op. 22 The Swan of Tuonela . 9:11 9 5 Pieces – piano, Op. 85 No. 2 Carnation . .. 1:35 0 Symphony No.2 in D, Op. 43 IV. Finale . 13:30 Total Timing . 67:06 FOR FULL LIST OF SIBELIUS RECORDINGS WITH ARTIST DETAILS AND FOR A GLOSSARY OF MUSICAL TERMS PLEASE GO TO WWW.NAXOS.COM 552135-36bk VBO Sibelius 7/8/06 9:17 PM Page 2 JEAN SIBELIUS (1865–1957) To explore the Nordic world of Sibelius, we recommend: Orchestral Works Symphonies Nos. -

7 X 11.5 Double Line.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-03357-2 - Sibelius Studies Edited by Timothy L. Jackson and Veijo Murtomaki Index More information Index Abraham, Gerald, 32, 37, 296, 310, 316, An die ferne Geliebte, 194, 207, 249 321, 323, 350 Symphony No. 5, 251 Ackté, Aino, 31, 101 Symphony No. 7, 201–03, 260 Adams, John, xi Symphony No. 9, 70, 239 Adorno, Theodor, xi–xiv, xviii–xix, Benjamin, George, 56 10–11, 29, 36 Berg, Alban, xi, 29, 243 Ahlquist-Oksanen, August, 104, 133 Berg, Helene, 243 Ahnger, Alexandra, 30 Berglund, Paavo, 17, 30 Aho, Kalevi, 96 Bernstein, Leonard, 24 Ainola, 99, 178–79, 322 Bizet, Georges, 124 Allen, Roger, 62 Björling, Jussi, 32 Amishai-Maisels, Ziva, 177 Bjurha, Gottfried, 85, 89 Anderson, Marian, 31 Bobrikoff, Nicolai Ivanovich, 135 Andersson, Otto, 298–99 Böcklin, Arnold, 77–78 Ansermet, Ernest, 24 Böhm, Karl, 23 Antokoletz, Elliott, xii, xvii, xviii Borg, Kim, 32–33 Ashkenazy,Vladimir, 33 Bosley, Keith, 65, 158 Attali, Jacques, 9 Bosse, Harriet, 85 auxiliary cadence, 187, 265 Boult, Sir Adrian, 15 bitonic, 189, 200, 214–24 Brahms, Johannes, 32, 35, 36–37, 56, initial, 187–88, 210 61–62, 126, 178–80, 187, 189, internal, 187, 201, 210, 213 194–95, 198, 200, 226, 238, 243, linked, 187, 190, 212, 221 261, 265, 269, 272, 315 monotonic, 189, 195 Piano Quartet in C minor, 251 nested, 187, 188, 190, 214 Symphony No. 1, 126, 238, 240–43, over-arching, 187–88, 195, 198, 201, 251–60, 268–69, 272 203 Symphony No. 3, 187, 193, 195–97, tonic, 177, 188–89, 200–06, 226–38, 226, 260, 269 231, 260 Symphony No. -

Download Booklet

BIS-CD-1295 Sib Film 8/22/03 11:11 AM Page 3 9 The Swan of Tuonela, Op. 22 No. 2 (1893, rev. 1897, 1900) BIS-CD-1015 9'27 from Lemminkäinen Suite (Four Legends from the Kalevala) (Breitkopf & Härtel) 10 Valse triste, Op. 44 No. 1 (1903, rev. 1904) (Breitkopf & Härtel) BIS-CD-915 4'42 from the incidental music to the play Kuolema (Death) by Arvid Järnefelt from Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43 (1901-02) (Breitkopf & Härtel) 11 I. Allegretto BIS-CD-862 9'14 12 Andante festivo, JS 34b (1922/c.1930) (Fazer) 5'18 for strings and timpani Lahti Symphony Orchestra (Sinfonia Lahti) conducted by Osmo Vänskä Jaakko Kuusisto, violin Folke Gräsbeck, piano Titles given within [square brackets] are ‘working titles’ for pieces to which Sibelius gave no ‘official’ name’. 3 BIS-CD-1295 Sib Film 8/22/03 11:11 AM Page 4 ibelius matured as a composer in a period characterized by the powerful emergence Sof Finnish nationalism. His family was Swedish-speaking, but he attended a Finnish- speaking secondary school and became acquainted with the mythology of the Kalevala and with Finnish-language literature. He studied at the Helsinki Music Institute and went on to study in Berlin and Vienna. Sibelius’s works from the 1890s are very Finnish in tone, but during the first decade of the 20th century he began to turn towards a more international and classical idiom. In recognition of his importance as a national cultural figure, he was granted a small government pension, although this was more of symbolic importance than a significant contribution to his income. -

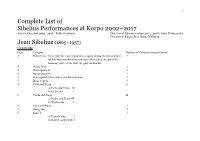

Complete List of Sibelius Performances at Korpo 2002–2017

!1 Complete List of Sibelius Performances at Korpo 2002–2017 Artistic Director 2002–2018: Folke Gräsbeck Director of Administration 2012–2018: Petri Kirkkomäki Director of Korpo Jazz: Bosse Mellberg Jean Sibelius (1865–1957) Contents Page Category Number of Compositions performed 3 Piano Trios. These form the most important category during the two summers 7 of Sibelius’s family visits to Korpo. Hence they are given the honorary place as the first category on this list. 4 String Trios. 2 4 Piano Quartets. 3 4 String Quartets. 9 5 Piano Quintet, Ensembles and Melodramas. 4 5 Brass Septets. 5 5 Cello and Piano. 11 a) Cello and Piano 10 b) Cello solo 1 6 Violin and Piano. 46 a) Violin and Piano 44 b) Violin solo 2 8 Viola and Piano. 1 8 String duo. 4 8 Kantele. 3 a) Kantele solo 2 b) Kantele and Violin 1 !2 9 Piano Solo. 56 12 Recitation and Piano. 3 12 Voice and Piano. 80 16 Lithurgical Music and Organ Music. 2 17 Mixed Choir. 7 18 Female or Youth Choir. 6 18 Male Choir. 13 19 Chamber or String Orchestra. 8 20 Symphony Orchestra. 2 Altogether 272 Opus or Year of Title + English Year of JS No. composition translation performance Piano Trios - - 1882–85 [Minuetto] in D minor 2011 - - 1883–85 [Andante] in A minor – Adagio – Allegro maestoso in E flat major, 2011 World Première Performance 2011 JS 206 1884 Piano Trio in A minor 2004, 2010 - - Hafträsk 1886 [Andantino], fragment in A major 2003–04, 2011 Completed by Jaakko Kuusisto, World Première Performance 2003 JS 27 Hafträsk 1886 Allegro in D major 2004–05, 2008–09 JS 207 Hafträsk 1886 Piano Trio in A minor ‘Hafträsk’ 2002–03, 2005, 2007, 2008 (II), 2011, 2016, Piano Trio in A minor ‘Hafträsk’, including the 1.