Japanese-Mongolian Relations, 1873-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REVOLUTION GOES EAST Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

REVOLUTION GOES EAST Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University were inaugu rated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and contemporary East Asia. REVOLUTION GOES EAST Imperial Japan and Soviet Communism Tatiana Linkhoeva CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of New York University. Learn more at the TOME website, which can be found at the following web address: openmono graphs.org. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International: https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress. cornell.edu. Copyright © 2020 by Cornell University First published 2020 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Linkhoeva, Tatiana, 1979– author. Title: Revolution goes east : imperial Japan and Soviet communism / Tatiana Linkhoeva. Description: Ithaca [New York] : Cornell University Press, 2020. | Series: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019020874 (print) | LCCN 2019980700 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501748080 (pbk) | ISBN 9781501748097 (epub) | ISBN 9781501748103 (pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Communism—Japan—History—20th century. -

<全文>Japan Review : No.34

<全文>Japan review : No.34 journal or Japan review : Journal of the International publication title Research Center for Japanese Studies volume 34 year 2019-12 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1368/00007405/ 2019 PRINT EDITION: ISSN 0915-0986 ONLINE EDITION: ISSN 2434-3129 34 NUMBER 34 2019 JAPAN REVIEWJAPAN japan review J OURNAL OF CONTENTS THE I NTERNATIONAL Gerald GROEMER A Retiree’s Chat (Shin’ya meidan): The Recollections of the.\ǀND3RHW+H]XWVX7ǀVDNX R. Keller KIMBROUGH Pushing Filial Piety: The Twenty-Four Filial ExemplarsDQGDQ2VDND3XEOLVKHU¶V³%HQH¿FLDO%RRNVIRU:RPHQ´ R. Keller KIMBROUGH Translation: The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars R 0,85$7DNDVKL ESEARCH 7KH)LOLDO3LHW\0RXQWDLQ.DQQR+DFKLUǀDQG7KH7KUHH7HDFKLQJV Ruselle MEADE Juvenile Science and the Japanese Nation: 6KǀQHQ¶HQDQGWKH&XOWLYDWLRQRI6FLHQWL¿F6XEMHFWV C ,66(<ǀNR ENTER 5HYLVLWLQJ7VXGD6ǀNLFKLLQ3RVWZDU-DSDQ³0LVXQGHUVWDQGLQJV´DQGWKH+LVWRULFDO)DFWVRIWKH.LNL 0DWWKHZ/$5.,1* 'HDWKDQGWKH3URVSHFWVRI8QL¿FDWLRQNihonga’s3RVWZDU5DSSURFKHPHQWVZLWK<ǀJD FOR &KXQ:D&+$1 J )UDFWXULQJ5HDOLWLHV6WDJLQJ%XGGKLVW$UWLQ'RPRQ.HQ¶V3KRWRERRN0XUǀML(1954) APANESE %22.5(9,(:6 COVER IMAGE: S *RVRNXLVKLNLVKLNL]X御即位式々図. TUDIES (In *RVRNXLGDLMǀVDLWDLWHQ]XDQ7DLVKǀQREX御即位大甞祭大典図案 大正之部, E\6KLPRPXUD7DPDKLUR 下村玉廣. 8QVǀGǀ © 2019 by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Please note that the contents of Japan Review may not be used or reproduced without the written permis- sion of the Editor, except for short quotations in scholarly publications in which quoted material is duly attributed to the author(s) and Japan Review. Japan Review Number 34, December 2019 Published by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies 3-2 Goryo Oeyama-cho, Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto 610-1192, Japan Tel. 075-335-2210 Fax 075-335-2043 Print edition: ISSN 0915-0986 Online edition: ISSN 2434-3129 japan review Journal of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies Number 34 2019 About the Journal Japan Review is a refereed journal published annually by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies since 1990. -

Ewa Pałasz-Rutkowska the Russo-Japanese War and Its Impact on Polish‑Japanese Relations in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

Ewa Pałasz-Rutkowska The Russo-Japanese war and its impact on Polish‑Japanese relations in the first half of the twentieth century Analecta Nipponica 1, 11-43 2011 ARTICLES Ewa Pałasz-Rutkowska THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR AND ITS IMPACT ON THE POLISH-JAPANESE RELATIONS IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY1 The Russo-Japanese War and its effects undoubtedly influenced the internatio- nal situation and directly affected Poland as well as Polish-Japanese relations, in the short as well as the long run. In the short run – that is, during the war itself – various political forces in Poland (e.g. Polish Socialist Party, National League) sought to exploit it for their own ends (including the restoration of an indepen- dent Polish state), establishing direct contacts with representatives of the Japanese government. At the same time, Poles exhibited much greater interest in Japan as a country which, less than 40 years after it ended its isolation and began to mod- ernize, had the courage to launch a war against mighty imperial Russia, Poland’s primary enemy at the time. This interest was reflected in numerous (for the era) Polish publications about Japan, including indirect translations of Japanese litera- ture (Okakura Kakuzō 岡倉覚三, Nitobe Inazō 新渡戸稲造, Tokutomi Roka 徳富 蘆花, translations of works by Westerners who had visited Japan (Wilhelm Dep- ping, Henry Dumolard, Rudyard Kipling, Georges Weulerse) and works by Poles, including books and articles in the press. The impact of the war in the short run: 1904–1905 Genesis: Poland and Japan prior to 1904 Due to unfavorable historical circumstances – i.e. -

Sample Chapter

Constructing Empire The Japanese in Changchun, 1905–45 Bill Sewell Sample Material © UBC Press 2019 Contents List of Illustrations / vii Preface / ix List of Abbreviations / xv Introduction / 9 1 City Planning / 37 2 Imperialist and Imperial Facades / 64 3 Economic Development/ 107 4 Colonial Society / 131 Conclusion / 174 Notes / 198 Bibliography / 257 Index / 283 Sample Material © UBC Press 2019 Introduction The city of Changchun, capital of the landlocked northeastern province of Jilin, might seem an odd place in which to explore Japan’s pre-war empire. Just over fifteen hundred kilometres from Tokyo, Changchun is not quite as far away as the Okinawan capital, Naha, but lies inland more than six hundred kilometres north of Dalian and Seoul and five hundred kilometres west of Vladivostok. Cooler and drier than Japan, its continental climate compounds its remoteness by making it, for Japanese, a different kind of place. Changchun, moreover, has rarely graced international headlines in recent years, given Jilin’s economic development’s lagging behind the coastal provinces, though the city did host the 2007 Asian Winter Games. In the twentieth century’s first half, however, Changchun figured prominently. The Russo-Japanese War resulted in its becoming the boundary between the Russian and Japanese spheres of influence in northeast China and a transfer point for travel between Europe and Asia. The terminus of the broad-gauge Russian railroad track required a physical transfer to different trains, and, before 1917, a twenty-three- minute difference between Harbin and Dalian time zones required travellers to reset their watches.1 Following Japan’s seizure of Manchuria, Changchun, renamed Xinjing, became the capital of the puppet state of Manchukuo, rec- ognized by the Axis powers and a partner in Japan’s Greater East Asia Co- Prosperity Sphere. -

Fukushima Yasumasa and Utsunomiya Tarō on the Edge of the Silk Road: Pan-Asian Visions and the Network of Military Intelligence

CHAPTER 4 Fukushima Yasumasa and Utsunomiya Tarō on the Edge of the Silk Road: Pan-Asian Visions and the Network of Military Intelligence from the Ottoman and Qajar Realms into Central Asia Selçuk Esenbel During the Meiji period, Japanese diplomats were locked in the frustrating de- bate about “extraterritoriality” in the Japanese and Turkish negotiations for the prospect of signing a treaty of trade and diplomacy—a debate that lingered on for many decades during the nineteenth century, and was not to be resolved until 1924 when, after the demise of the Ottoman Empire at the end of WWI, the recently established Republic of Turkey abolished the capitulatory treaty sys- tem of extraterritoriality and other privileges that were customarily accorded to the Western powers. The discussion of a desirable treaty between Japan and the Ottoman Empire had begun initially in 1880–1881 when the first Japanese Mission to the Middle East of seven members including Captain Furukawa Nobuyoshi of the recently established General Staff of the Imperial Army and a number of Japanese businessmen who hoped to sell tea and sundry items in the Middle East markets. Headed by special envoy Yoshida Masaharu the Mission to the Muslim polities visited the courts of Qajar Iran and Ottoman Turkey that consisted of a long stay of three months during the fall of 1880 in Teheran, the capital of the Persian kingdom, and after an investigation journey through the Caucasus arrived in the Ottoman capital, Istanbul, to stay for three weeks in March 1881 before departure to go back home to Japan. -

Trabajo Fin De Máster

Trabajo Fin de Máster EL GRABADO JAPONÉS EN LA COLECCIÓN DE EMILIO BUJALANCE: LA GUERRA SINO-JAPONESA (1894- 1895) THE JAPANESE PRINT IN EMILIO BUJALANCE´S COLLECTION: THE SINO-JAPANESE WAR (1894-1895) Autor Macarena Angulo Cabeza Director V. David Almazán Tomás Facultad de Filosofía y Letras 2017 ÍNDICE 1. RESUMEN ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................................................ 2 2.1. Justificación del tema del trabajo .............................................................................. 2 2.2. Estado de la cuestión ................................................................................................... 3 2.3. Objetivos .................................................................................................................... 14 2.4. Metodología ............................................................................................................... 15 3. EL GRABADO JAPONÉS EN LA COLECCIÓN DE EMILIO BUJALANCE: LA GUERRA SINO-JAPONESA (1894-1895) ................................................................................ 16 3.1. Colección Bujalance .................................................................................................. 16 3.1.1. Datos biográficos del coleccionista Emilio Bujalance ........................................ 16 3.1.2. Colección Bujalance ........................................................................................... -

The Battle of Malaya: the Japanese Invasion of Malaya As a Case Study for the Re-Evaluation of Imperial Japanese Army Intelligence Effectiveness During World War Ii

THE BATTLE OF MALAYA: THE JAPANESE INVASION OF MALAYA AS A CASE STUDY FOR THE RE-EVALUATION OF IMPERIAL JAPANESE ARMY INTELLIGENCE EFFECTIVENESS DURING WORLD WAR II A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts By DANIEL J. LAURO B.A., Wright State University, 2015 2018 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL April 20, 2018 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Daniel J. Lauro ENTITLED: The Battle of Malaya: The Japanese Invasion Of Malaya as a Case Study for the Re-Evaluation of Imperial Japanese Army Intelligence Effectiveness During World War II BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of the Arts. ___________________________ Kathryn Meyer , Ph.D. Thesis Director ___________________________ Jonathan Reed Winkler, Ph.D. Chair, Department of History Committee on Final Examination ___________________________ Kathryn Meyer, Ph.D. ___________________________ Jonathan Reed Winkler, Ph.D. ___________________________ Paul Lockhart, Ph.D. ___________________________ Barry Milligan, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Lauro, Daniel J. M.A. Department of History, Wright State University, 2018. The Battle of Malaya: The Japanese Invasion of Malaya as a Case Study for the Re-Evaluation of Imperial Japanese Army Intelligence Effectiveness During World War II. The present assessment of Japanese intelligence operations during World War II is based almost entirely upon the work of Western researchers. The view presented is one of complete incompetence by the West. Little attention has been paid to any successes the Japanese intelligence organizations achieved. In fact, the majority of Anglo-American historians have instead focused on the errors and unpreparedness of the Allies as the cause of their early failures. -

Faith, Race and Strategy: Japanese-Mongolian Relations, 1873-1945

FAITH, RACE AND STRATEGY: JAPANESE-MONGOLIAN RELATIONS, 1873-1945 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2008 James Boyd (BA (Hons) Adelaide) I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………. ABSTRACT Between 1873 and 1945 Japan and Mongolia had a complex and important relationship that has been largely overlooked in post-war studies of Japan’s imperial era. In fact, Japanese-Mongolian relations in the modern period provide a rich field of enquiry into the nature of Japanese imperialism as well as further evidence of the complexity of Japan’s relationships with other Asian countries in the decades before 1945. This thesis examines the relationship from the Japanese perspective, drawing on a diverse range of contemporary materials, both official and unofficial, including military documents, government reports, travel guides and academic works, many of which have been neglected in earlier studies. In previous analyses, the strategic dimension has been seen as overwhelming and Mongolia has often been regarded as merely a minor addendum to Japan’s relationship with Manchuria. In fact, however, Japan’s connection with Mongolia itself was a crucial part of its interaction with the Chinese continent from the 1870s to 1945. Though undeniably coveted for strategic reasons, Mongolia also offered unparalleled opportunities for the elaboration of all the major aspects of the discourses that made up Japan’s evolving claim to solidarity with and leadership of Asia. -

Clouds Above the Hill

Clouds above the Hill Clouds above the Hill, a longtime best-selling novel in Japan, is now translated into English for the first time. An epic portrait of Japan in crisis, it combines graphic military history and highly readable fiction to depict an aspiring nation modernizing at breakneck speed. Acclaimed author Shiba Ryōtarō devoted an entire decade of his life to this extraordinary blockbuster, which features Japan’s emergence onto the world stage by the early years of the twentieth century. Volume III finds Admiral Tōgō continuing his blockade of Port Arthur. Meanwhile, a Japanese land offensive gains control of the high ground overlooking the bay as the Russians at last call for a ceasefire. However, on the banks of the Shaho River, the Japanese lines are stretched, but the Russian General Kuropatkin makes a decision to flank the troops to the left and in doing so encounters Akiyama Yoshifuru’s cavalry. Anyone curious as to how the “tiny, rising nation of Japan” was able to fight so fiercely for its survival should look no further. Clouds above the Hill is an exciting, human portrait of a modernizing nation that goes to war and thereby stakes its very existence on a desperate bid for glory in East Asia. Shiba Ryōtarō (1923–1996) is one of Japan’s best-known writers, acclaimed for his direct tone and insightful portrayals of historic personalities and events. He was drafted into the Japanese Army, served in the Second World War, and subsequently worked for the newspaper Sankei Shimbun. He is most famous for his numerous works of historical fiction. -

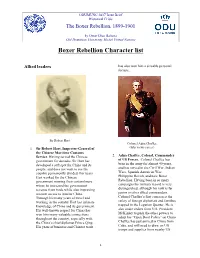

Boxer Rebellion Character List

ODUMUNC 2017 Issue Brief Historical Crisis The Boxer Rebellion, 1899-1901 by Omar Diaz Bahena Old Dominion University Model United Nations Boxer Rebellion Character list Allied leaders has also won him a sizeable personal fortune. Sir Robert Hart Colonel Adna Chaffee 1. Sir Robert Hart, Inspector-General of (later in his career) the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. Having served the Chinese 2. Adna Chaffee, Colonel, Commander government for decades, Sir Hart has of US Forces. Colonel Chaffee has developed a soft spot for China and its been in the army for almost 40 years, people, and does not want to see the and has served in the Civil War, Indian country permanently divided. For years Wars, Spanish American War, Hart worked for the Chinese Philippine Revolt, and now Boxer government running their customhouse Rebellion. Having been in so many where he increased the government campaigns his military record is very revenue from trade while also improving distinguished, although his rank is far western access to interior China. junior to other allied commanders. Through his many years of travel and Colonel Chaffee’s first concern is the working in the country Hart has intimate safety of foreign diplomats and families knowledge of China and its government. trapped in the Legation Quarter. He is His well-known respect for China has also under orders from U.S. President won him many valuable connections McKinley to push the other powers to throughout the country, especially with adopt his “Open Door Policy” on China. the China’s chief diplomat Prince Qing. Chaffee has just arrived in China from His years of business and Chinese trade Cuba, and will need to draw on US troops and supplies from nearby US 1 The Boxer Rebellion, 1899-1901 positions in the Pacific like the governorship over the island until the Philippines if the US is to play a major crisis is over. -

Japanische Offiziere Im Deutschen Kaiserreich, 1870-1914

Japanische Offiziere im Deutschen Kaiserreich 1870–1914 Rudolf Hartmann, Berlin Beim Aufbau der japanischen Streitkräfte, insbesondere des Heeres, nach der Meiji Restauration spielte das deutsche Kaiserreich1 eine wichtige Rolle. Der vorliegende Beitrag erfaßt Offiziere, die vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nach Deutschland kamen, um sich das Rüstzeug für die Gestaltung moderner Streit- kräfte anzueignen. Sie repräsentierten etwa zwei Drittel aller zu diesem Zweck ins Ausland Delegierten. Ein Militärbericht von 1902 aus der deutschen Ge- sandtschaft in Tokyo besagt z.B., daß am 25. Mai 1902 insgesamt 42 japanische Offiziere “zu ihrer weiteren militärischen Ausbildung” kommandiert wurden, von denen sich “in Deutschland 28, in Frankreich 9, in Österreich 2 und in England 3”2 aufhielten. Seit 1870, als die ersten Offiziere zur militärischen und zivilen Schulung eintrafen, stieg ihre Zahl bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg auf insgesamt über 450 an und verfünffachte sich nahezu von 36 in den 1870er Jahren auf 168 in der ersten Dekade des 20. Jahrhunderts.3 In Liste 1 wurden Personen aufgenommen, die sich – vom Heeres- oder Marineministerium entsandt – zeitlich über mehrere Monate oder Jahre zu militärischen Studien und / oder praktischen Übungen in Deutschland aufhiel- ten. Ebenso sind jene vermerkt, die zur Aneignung technischer Kenntnisse und Fertigkeiten oder zu medizinischen Übungen in Hospitäler und Lazarette 1 Der Einfachheit halber ist im folgenden von “Deutschland” die Rede. 2 Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes, Abt. A.: Acten betreffend Militär- und Marine- Angelegenheiten. Japan 2 (im folgenden: Auswärtiges Amt, PA, Japan 2), Bd. 6, Militär- bericht vom 29.6.1902. Nicht einbezogen wurden Militärattachés sowie solche, die sich in China, Korea und Russland aufhielten. -

Japanische Frauen – Ein Leitbild Im Wandel

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2006 Japanische Frauen - ein Leitbild im Wandel : die Zeitschrift Shufu no tomo 1917-1935 Gross, Christine Abstract: Eine auch in Japan weit verbreitete Vorstellung einer „richtigen“ Frau ist die der Hausfrau und Mutter in der Familie. Dieses Ideal gilt zwar häufig als jahrhundertealte Tradition, hat sich aber (wie die Lebensweise als Hausfrau) im Wesentlichen im Zuge der Modernisierung nach der Meiji-Restauration von 1868 herausgebildet. Die Frage, wie es sich verbreitete und in praktisch allen Bevölkerungsschichten Einfluss gewann, bildet den Hintergrund für die vorliegende Studie zu Shufu no tomo („Freundin der Hausfrau“), einer der bedeutendsten japanischen Frauenzeitschriften der ersten Hälfte des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. Im Zentrum der Untersuchung stehen die in dieser Publikation zu findenden normativen Vorstellungen idealer Weiblichkeit und ihr Wandel in der Zwischenkriegszeit. Den Anfang machen zwei einführende Kapitel zur Situation der Frauen und zur Entwicklung der Frauenzeitschriften in Japan von der zweiten Hälfte des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts bis Mitte der Dreissigerjahre. Den Hauptteil bilden die Abschnitte 3 und 4 zu Shufu no tomo: In Kapitel 3 wird die Zeitschrift, ihre Entstehung und allgemeine Entwicklung zwischen 1917 und 1935 beschrieben. In Kapitel 4 geht es um die Analyse der Publikation anhand ausgewählter Artikel im Hinblick auf die in ihr vermittelten Frauenleitbilder. Die Studie zeigt, dass das von der Zeitschrift verbreitete Leitbild bezüglich der in dieser Arbeit berücksichtigten zwei Aspekte – des für Frauen als angemessen geltenden Handlungsraums und ihrer Stellung innerhalb der Familie – trotz grosser Kontinuitäten erhebliche Variationen aufwies und sich, in engem Zusammenhang mit dem allgemeinen sozialen Wandel, rasch veränderte.