Surnames and National Identity in Turkey and Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Pre-Genocide

Pre- Genocide 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 1 23/08/2018 11.51 © The contributors and Humanity In Action (Denmark) 2018 Editors: Anders Jerichow and Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke Printed by Tarm Bogtryk Design: Rie Jerichow Translations from Danish: Anders Michael Nielsen ISBN 978-87-996497-1-6 Contributors to this anthology are unaware of - and of course not liable for – contributions other than their own. Thus, there is no uniform interpretation of genocides, nor a common evaluation of the readiness to protect today. Humanity In Action and the editors do not necessarily share the authors' assessments. Humanity In Action (Denmark) Dronningensgade 14 1420 Copenhagen K Phone +45 3542 0051 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 2 23/08/2018 11.51 Anders Jerichow and Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke (ed.) Pre-Genocide Warnings and Readiness to Protect Humanity In Action (Denmark) 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 3 23/08/2018 11.51 Contents Judith Goldstein Preparing ourselves for the future .................................................................. 6 Anders Jerichow: Introduction: Never Again? ............................................................................ 8 I. Genocide Armenian Nation: Inclusion and Exclusion under Ottoman Dominance – Taner Akcam ........... 22 Germany: Omens, hopes, warnings, threats: – Antisemitism 1918-1938 - Ulrich Herbert ............................................................................................. 30 Poland: Living apart – Konstanty Gebert ................................................................... -

Monday, June 28, 2021

STATE OF MINNESOTA Journal of the Senate NINETY-SECOND LEGISLATURE SPECIAL SESSION FOURTEENTH DAY St. Paul, Minnesota, Monday, June 28, 2021 The Senate met at 10:00 a.m. and was called to order by the President. The members of the Senate paused for a moment of silent prayer and reflection. The members of the Senate gave the pledge of allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. The roll was called, and the following Senators were present: Abeler Draheim Howe Marty Rest Anderson Duckworth Ingebrigtsen Mathews Rosen Bakk Dziedzic Isaacson McEwen Ruud Benson Eaton Jasinski Miller Senjem Bigham Eichorn Johnson Murphy Tomassoni Carlson Eken Johnson Stewart Nelson Torres Ray Chamberlain Fateh Kent Newman Utke Champion Franzen Kiffmeyer Newton Weber Clausen Frentz Klein Osmek Westrom Coleman Gazelka Koran Pappas Wiger Cwodzinski Goggin Kunesh Port Wiklund Dahms Hawj Lang Pratt Dibble Hoffman Latz Putnam Dornink Housley Limmer Rarick Pursuant to Rule 14.1, the President announced the following members intend to vote under Rule 40.7: Abeler, Carlson (California), Champion, Eaton, Eichorn, Eken, Fateh, Goggin, Hoffman, Howe, Kunesh, Lang, Latz, Newman, Newton, Osmek, Putnam, Rarick, Rest, Torres Ray, Utke, and Wiklund. The President declared a quorum present. The reading of the Journal was dispensed with and the Journal, as printed and corrected, was approved. MOTIONS AND RESOLUTIONS Senators Wiger and Chamberlain introduced -- Senate Resolution No. 12: A Senate resolution honoring White Bear Lake Mayor Jo Emerson. Referred to the Committee on Rules and Administration. 1032 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE [14TH DAY Senator Gazelka moved that H.F. No. 2 be taken from the table and given a second reading. The motion prevailed. H.F. -

Angels Or Monsters?: Violent Crimes and Violent Children in Mexico City, 1927-1932 Jonathan Weber

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Angels or Monsters?: Violent Crimes and Violent Children in Mexico City, 1927-1932 Jonathan Weber Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ANGELS OR MONSTERS?: VIOLENT CRIMES AND VIOLENT CHILDREN IN MEXICO CITY, 1927-1932 BY JONATHAN WEBER A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jonathan Weber defended on October 6, 2006. ______________________________ Robinson Herrera Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Rodney Anderson Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Upchurch Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The first person I owe a great deal of thanks to is Dr. Linda Arnold of Virginia Tech University. Dr. Arnold was gracious enough to help me out in Mexico City by taking me under her wing and showing me the ropes. She also is responsible for being my soundboard for early ideas that I “bounced off” her. I look forward to being able to work with her some more for the dissertation. Another very special thanks goes out to everyone at the AGN, especially the janitorial staff for engaging me in a multitude of conversations as well as the archival cats that hang around outside (even the one who bit me and resulted in a series of rabies vaccinations begun in the Centro de Salud in Tlalpan). -

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi V. Migdal Cooperative Village 1

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi v. Migdal Cooperative Village 1 CA 6821/93 LCA 1908/94 LCA 3363/94 United Mizrahi Bank Ltd. v. 1. Migdal Cooperative Village 2. Bostan HaGalil Cooperative Village 3. Hadar Am Cooperative Village Ltd 4. El-Al Agricultural Association Ltd. CA 6821/93 1. Givat Yoav Workers Village for Cooperative Agricultural Settlement Ltd 2. Ehud Aharonov 3. Aryeh Ohad 4. Avraham Gur 5. Amiram Yifhar 6. Zvi Yitzchaki 7. Simana Amram 8. Ilan Sela 9. Ron Razon 10. David Mini v. 1. Commercial Credit Services (Israel) Ltd 2. The Attorney General LCA 1908/94 1. Dalia Nahmias 2. Menachem Nahmias v. Kfar Bialik Cooperative Village Ltd LCA 3363/94 The Supreme Court Sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals [November 9, 1995] Before: Former Court President M. Shamgar, Court President A. Barak, Justices D. Levine, G. Bach, A. Goldberg, E. Mazza, M. Cheshin, Y. Zamir, Tz. E Tal Appeal before the Supreme Court sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals 2 Israel Law Reports [1995] IsrLR 1 Appeal against decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) on 1.11.93 in application 3459/92,3655, 4071, 1630/93 (C.F 1744/91) and applications for leave for appeal against the decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) dated 6.3.94 in application 5025/92 (C.F. 2252/91), and against the decision of the Haifa District Court (Judge S. Gobraan), dated 30.5.94 in application for leave for appeal 18/94, in which the appeal against the decision of the Head of the Execution Office in Haifa was rejected in Ex.File 14337-97-8-02. -

The Mentons. Wasit a Crime?

N T E C O N T S . CHAP TE R . PAGE - I . OLD EN MI S M T E E EE , — II . AM ID R TOR TS AN D ! URNAC S E E , IIL—B A TI! L H L N M NTON E U U E E E E , I - A V. I T W S HAR D LY M R D R U E , f “ - V . WH Y NOT M OR THAN ! R I NDS E E , —I A VI I T W S A SW LL N IG HT AT THE M NTON S E E , ” II SHE IS A HE D I V . S V L E , III M Y OD T IS IS A ! V . G ! H W L U , — IX . B UT IS IT RETRIB UTION ! RETRI B U TION 1 “ — C D D K X . I ALL GO TO WITNESS THAT I D I NOT ILL PA L D NM AN U E , X —HE R HAND R LAX D ITS HOLD U P ON THE R AIL I . E E I N G AND SH ! LL ! R OM TH WITN SS CHAIR , E E E E , “ ” XII — THANK OD TH IS LIG HT AH AD . G R E E E , — G P XIII . A B URNING DESIRE ! OR R EVEN E U ON THE M AN W H O HAD ROB B D ME O! M Y LOV E E , ” XIV. N OT G ILTY U , — I K O! TRE A ! U L EAN CE HE WREAK ED XV. TH N W VEN G S THROUGH YOU . -

Toadies Vaden Todd Lewis - Vocals, Guitar Clark Vogeler - Guitar Mark Reznicek – Drums Doni Blair - Bass

Toadies Vaden Todd Lewis - vocals, guitar Clark Vogeler - guitar Mark Reznicek – drums Doni Blair - bass “There’s a certain uneasiness to the Toadies,” says Vaden Todd Lewis, succinctly and accurately describing his band—quite a trick. The Texas band is, at its core, just a raw, commanding rock band. Imagine an ebony sphere with a corona that radiates impossibly darker, and a brilliant circular sliver of light around that. It’s nebulous, but strangely distinct—and, shall we say incorrect. Or, as Lewis says, “wrong.” “Things are done a little askew [in the Toadies],” he says, searching for the right words. “There’s just something wrong with it that’s just really cool… and unique in a slightly uncomfortable way.” This sick, twisted essence was first exemplified on the band’s 1994 debut, Rubberneck (Interscope). An intense, swirling vortex of guitar rock built around Lewis’s “wrong” songs—like the smash single “Possum Kingdom,” subject to as much speculation as what’s in the Pulp Fiction briefcase, it rocketed to platinum status on the strength of that and two other singles, “Tyler” and “Away.” Its success was due to the Toadies’ organic sound and all-encompassing style, which they aimed to continue on their next album. Perhaps in keeping with the uneasy vibe, that success didn’t translate to label support when the Toadies submitted their second album, Feeler. Perhaps aptly, things in general just went wrong. It was the classic, cruel story: the label didn’t ‘get’ it. “These were the songs we played live,” says Rez. “It was pretty eclectic… different styles of heavy rock music—some fast, heavy punk rock songs and some slower, kinda mid-tempo stuff. -

Ardis 1990. Каталог Издательства. — Ann Arbor : Ardis. 1990

C 0 NTENT S New and Forthcoming in Hardback ..............................................3 The Prose of the Russian Poets Series ............................................8 New and Forthcoming in Paperback ..............................................9 Twentieth-Century Literature Backlist ........................................10 Nineteenth-Century Literature Backlist ....................................... 12 Miscellaneous ................................................................................ 13 Literary Criticism ..........................................................................14 Russian Literature Triquarterly ....................................................16 Language Instruction ....................................................................16 Books in Russian ...........................................................................17 Books in Print-English .................................................................19 Books in Print-Russian .................................................................21 Ordering Information........................................................ ...........23 NOTE TO LIBRARIANS The following titles are announced for the first time: V. Nabokov. A Pictorial Biography .. ..... .. ......... ........ .... 3 After Russia ...... ..... .... ..... ..... ..... .... .... .... .... .... .... ..... ... 4 Disappearance . ..... .. .... ....... .... ... .... .... .. .... ..... ... ....... 5 An Ordinary Story .. ..... ...... .... .. ..... .. ...... .. ..... ... ... .. -

My Life's Story

My Life’s Story By Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz 1915-2000 Biography of Lieutenant Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Z”L , the son of Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Shwartz Z”L , and Rivka Shwartz, née Klein Z”L Gilad Jacob Joseph Gevaryahu Editor and Footnote Author David H. Wiener Editor, English Edition 2005 Merion Station, Pennsylvania This book was published by the Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Memorial Committee. Copyright © 2005 Yona Shwartz & Gilad J. Gevaryahu Printed in Jerusalem Alon Printing 02-5388938 Editor’s Introduction Every Shabbat morning, upon entering Lower Merion Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation on the outskirts of the city of Philadelphia, I began by exchanging greetings with the late Lt. Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz. He used to give me news clippings and booklets which, in his opinion, would enhance my knowledge. I, in turn, would express my personal views on current events, especially related to our shared birthplace, Jerusalem. Throughout the years we had an unwritten agreement; Eliyahu would have someone at the Israeli Consulate of Philadelphia fax the latest news in Hebrew to my office (Eliyahu had no fax machine at the time), and I would deliver the weekly accumulation of faxes to his house on Friday afternoons before Shabbat. This arrangement lasted for years. Eliyahu read the news, and distributed the material he thought was important to other Israelis and especially to our mutual friend Dr. Michael Toaff. We all had an inherent need to know exactly what was happening in Israel. Often, during my frequent visits to Israel, I found that I was more current on happenings in Israel than the local Israelis. -

Eytan 20 Jun 1990 Transcript

United Nations Oral History Project Walter Eytan 20 June 1990 r _. • ,<; .. iJ (()~ ~ NO~J-CIRCULATI NG ) YUN INTERVIEW lJ'" llBRf\R'LlBR;.\ t"!' . F( i Gr ~~- . ·'·'::::··,':;·'WALTER·'·'::::··.':;·'WALTER EYTAN ~ ~lr.J\~lr.J\!! : -~-'~, "' .... JUNE 20, 1990"1990 .. ,'U"'~~U'"'t''''1''1'l '.,J:'-C)LL'[ I ~ ......."",1"':Ll J "'co""""',,",,,,,, _ NEW YORK CITY, NEW YORK INTERVIEWER, JEAN KRASNO TABLE OF CONTENTCONTENTSS FOUNDING OF THE STATE OF ISRAEISRAELL positions Held by Mr. Eytan • . 1,2,4 The Jewish Agency ••• • . ... 2-5,7,10,11 The New York Delegation ... 4,5 statehood and Partition •••. • . ...... 6-9 UN Special Committee on Palestine .... 6-8,12,28 General Assembly ••••••.•....•... • • • • . • . • . .7,8,11 Jerusalem •••••• .- ••.....•.... 8-12,26,28,40 The Fighting •••• • • . ...11,12,24,29,39,40 The British Role . .13,18,19,21 Declaring Independence .15-18 The Palestine Committee . ... ... 19-21 The Truce •• . ... 22-24 UN Mediation •••••• • • • • . .25,26,27 Armistice Negotiations at Rhodes . .27-41 UN Conciliation Commission ...35,44,45 Mixed Armistice Commission • .39,41 UNTSO . ... •••••••......... • • • • . 42 1 JK: For the record, Mr. Eytan, could you please explain thethe role that you played during the time around thethe establishment of the state of Israel approximately between the years of 1947 and 1949? When did your involvement with Palestine begin? EytanEytan:: My involvement with Palestine began much earlier, inin 1933. But in 1933 there was no UN and all thesethese questions that you are raising don't really apply. In 1947 I was in Jerusalem. I was a member of the political department of the Jewish Agency for Palestine. -

Russia Outside Russia”: Transnational Mobility, Objects Of

“RUSSIA OUTSIDE RUSSIA”: TRANSNATIONAL MOBILITY, OBJECTS OF MIGRATION, AND DISCOURSES ON THE LOCUS OF CULTURE AMONGST EDUCATED RUSSIAN MIGRANTS IN PARIS, BERLIN, AND NEW YORK by Gregory Gan A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2019 © Gregory Gan, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: “Russia outside Russia”: Transnational Mobility, Objects of Migration, and Discourses on the Locus of Culture amongst Educated Russian Migrants in Paris, Berlin, and New York submitted by Gregory Gan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology Examining Committee: Dr. Alexia Bloch Supervisor Dr. Leslie Robertson Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Patrick Moore Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Nicola Levell University Examiner Dr. Katherine Bowers University Examiner Prof. Michael Lambek External Examiner ii Abstract This dissertation examines transnational Russian migration between Moscow, Berlin, Paris, and New York. In conversation with forty-five first- and second-generation Russian intellectuals who relocated from Russia and the former Soviet Union, the researcher investigates transnational Russian identity through ethnographic, auto-ethnographic, and visual anthropology methods. Educated migrants from Russia who shared with the researcher a comparable epistemic universe and experiential perspective, and who were themselves experts on migration, discuss what it means to belong to global transnational diasporas, how they position themselves in historical contexts of migration, and what they hope to contribute to modern intellectual migrant narratives. -

The Literary Fate of Marina Tsve Taeva, Who in My View Is One Of

A New Edition of the Poems of Marina Tsve taeva1 he literary fate of Marina Tsvetaeva, who in my view is one of the T most remarkable Russian poets of the twentieth century, took its ultimate shape sadly and instructively. The highest point of Tsve taeva’s popularity and reputation during her lifetime came approximately be- tween 1922 and 1926, i.e., during her first years in emigration. Having left Russia, Tsve taeva found the opportunity to print a whole series of collec- tions of poetry, narrative poems, poetic dramas, and fairy tales that she had written between 1916 and 1921: Mileposts 1 (Versty 1), Craft (Remes- lo), Psyche (Psikheia), Separation (Razluka), Tsar-Maiden (Tsar’-Devitsa), The End of Casanova (Konets Kazanovy), and others. These books came out in Moscow and in Berlin, and individual poems by Tsve taeva were published in both Soviet and émigré publications. As a mature poet Tsve- taeva appeared before both Soviet and émigré readership instantly at her full stature; her juvenile collections Evening Album (Vechernii al’bom) and The Magic Lantern (Volshebnyi fonar’) were by that time forgotten. Her success with readers and critics alike was huge and genuine. If one peruses émigré journals and newspapers from the beginning of the 1920s, one is easily convinced of the popularity of Marina Tsve taeva’s poetry at that period. Her writings appeared in the Russian journals of both Prague and Paris; her arrival in Paris and appearance in February 1925 before an overflowing audience for a reading of her works was a literary event. Soviet critics similarly published serious and sympathetic reviews. -

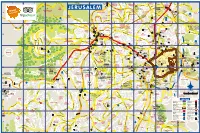

Jerusalem-Map.Pdf

H B S A H H A R ARAN H A E K A O RAMOT S K R SQ. G H 1 H A Q T V V HI TEC D A E N BEN G GOLDA MEIR I U V TO E R T A N U H M HA’ADMOR ESHKOL E 1 2 3 R 4 5 Y 6 DI ZAHA 7 MA H 8 E Z K A 9 INTCH. T A A MEGUR A E AR I INDUSTRY M SANHEDRIYYA GIV’AT Z L LOH T O O T ’A N Y A O H E PARA A M R N R T E A O 9 R (HAR HOZVIM) A Y V M EZEL H A A AM M AR HAMITLE A R D A A MURHEVET SUF I HAMIVTAR A G P N M A H M ET T O V E MISHMAR HAGEVUL G A’O A A N . D 1 O F A (SHAPIRA) H E ’ O IRA S T A A R A I S . D P A P A M AVE. Lev LEHI D KOL 417 i E V G O SH sh E k Y HAR O R VI ol L O I Sanhedrin E Tu DA M L AMMUNITION n n N M e E’IR L Tombs & Garden HILL l AV 436 E REFIDIM TAMIR JERUSALEM E. H I EZRAT T N K O EZRAT E E AV S M VE. R ORO R R L HAR HAMENUHOT A A A T E N A Z ’ Ammunition I H KI QIRYAT N M G TORA O 60 British Military (JEWISH CEMETERY) E HASANHEDRIN A N Hill H M I B I H A ZANS IV’AT MOSH H SANHEDRIYYA Cemetery QIRYAT SHEVA E L A M D Y G U TO MEV U S ’ L C E O Y M A H N H QIRYAT A IKH E .