Notes Cyber Crime 2.0: an Argument to Update the United States Criminal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Pre-Genocide

Pre- Genocide 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 1 23/08/2018 11.51 © The contributors and Humanity In Action (Denmark) 2018 Editors: Anders Jerichow and Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke Printed by Tarm Bogtryk Design: Rie Jerichow Translations from Danish: Anders Michael Nielsen ISBN 978-87-996497-1-6 Contributors to this anthology are unaware of - and of course not liable for – contributions other than their own. Thus, there is no uniform interpretation of genocides, nor a common evaluation of the readiness to protect today. Humanity In Action and the editors do not necessarily share the authors' assessments. Humanity In Action (Denmark) Dronningensgade 14 1420 Copenhagen K Phone +45 3542 0051 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 2 23/08/2018 11.51 Anders Jerichow and Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke (ed.) Pre-Genocide Warnings and Readiness to Protect Humanity In Action (Denmark) 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 3 23/08/2018 11.51 Contents Judith Goldstein Preparing ourselves for the future .................................................................. 6 Anders Jerichow: Introduction: Never Again? ............................................................................ 8 I. Genocide Armenian Nation: Inclusion and Exclusion under Ottoman Dominance – Taner Akcam ........... 22 Germany: Omens, hopes, warnings, threats: – Antisemitism 1918-1938 - Ulrich Herbert ............................................................................................. 30 Poland: Living apart – Konstanty Gebert ................................................................... -

Monday, June 28, 2021

STATE OF MINNESOTA Journal of the Senate NINETY-SECOND LEGISLATURE SPECIAL SESSION FOURTEENTH DAY St. Paul, Minnesota, Monday, June 28, 2021 The Senate met at 10:00 a.m. and was called to order by the President. The members of the Senate paused for a moment of silent prayer and reflection. The members of the Senate gave the pledge of allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. The roll was called, and the following Senators were present: Abeler Draheim Howe Marty Rest Anderson Duckworth Ingebrigtsen Mathews Rosen Bakk Dziedzic Isaacson McEwen Ruud Benson Eaton Jasinski Miller Senjem Bigham Eichorn Johnson Murphy Tomassoni Carlson Eken Johnson Stewart Nelson Torres Ray Chamberlain Fateh Kent Newman Utke Champion Franzen Kiffmeyer Newton Weber Clausen Frentz Klein Osmek Westrom Coleman Gazelka Koran Pappas Wiger Cwodzinski Goggin Kunesh Port Wiklund Dahms Hawj Lang Pratt Dibble Hoffman Latz Putnam Dornink Housley Limmer Rarick Pursuant to Rule 14.1, the President announced the following members intend to vote under Rule 40.7: Abeler, Carlson (California), Champion, Eaton, Eichorn, Eken, Fateh, Goggin, Hoffman, Howe, Kunesh, Lang, Latz, Newman, Newton, Osmek, Putnam, Rarick, Rest, Torres Ray, Utke, and Wiklund. The President declared a quorum present. The reading of the Journal was dispensed with and the Journal, as printed and corrected, was approved. MOTIONS AND RESOLUTIONS Senators Wiger and Chamberlain introduced -- Senate Resolution No. 12: A Senate resolution honoring White Bear Lake Mayor Jo Emerson. Referred to the Committee on Rules and Administration. 1032 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE [14TH DAY Senator Gazelka moved that H.F. No. 2 be taken from the table and given a second reading. The motion prevailed. H.F. -

Angels Or Monsters?: Violent Crimes and Violent Children in Mexico City, 1927-1932 Jonathan Weber

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Angels or Monsters?: Violent Crimes and Violent Children in Mexico City, 1927-1932 Jonathan Weber Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ANGELS OR MONSTERS?: VIOLENT CRIMES AND VIOLENT CHILDREN IN MEXICO CITY, 1927-1932 BY JONATHAN WEBER A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jonathan Weber defended on October 6, 2006. ______________________________ Robinson Herrera Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Rodney Anderson Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Upchurch Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The first person I owe a great deal of thanks to is Dr. Linda Arnold of Virginia Tech University. Dr. Arnold was gracious enough to help me out in Mexico City by taking me under her wing and showing me the ropes. She also is responsible for being my soundboard for early ideas that I “bounced off” her. I look forward to being able to work with her some more for the dissertation. Another very special thanks goes out to everyone at the AGN, especially the janitorial staff for engaging me in a multitude of conversations as well as the archival cats that hang around outside (even the one who bit me and resulted in a series of rabies vaccinations begun in the Centro de Salud in Tlalpan). -

The Mentons. Wasit a Crime?

N T E C O N T S . CHAP TE R . PAGE - I . OLD EN MI S M T E E EE , — II . AM ID R TOR TS AN D ! URNAC S E E , IIL—B A TI! L H L N M NTON E U U E E E E , I - A V. I T W S HAR D LY M R D R U E , f “ - V . WH Y NOT M OR THAN ! R I NDS E E , —I A VI I T W S A SW LL N IG HT AT THE M NTON S E E , ” II SHE IS A HE D I V . S V L E , III M Y OD T IS IS A ! V . G ! H W L U , — IX . B UT IS IT RETRIB UTION ! RETRI B U TION 1 “ — C D D K X . I ALL GO TO WITNESS THAT I D I NOT ILL PA L D NM AN U E , X —HE R HAND R LAX D ITS HOLD U P ON THE R AIL I . E E I N G AND SH ! LL ! R OM TH WITN SS CHAIR , E E E E , “ ” XII — THANK OD TH IS LIG HT AH AD . G R E E E , — G P XIII . A B URNING DESIRE ! OR R EVEN E U ON THE M AN W H O HAD ROB B D ME O! M Y LOV E E , ” XIV. N OT G ILTY U , — I K O! TRE A ! U L EAN CE HE WREAK ED XV. TH N W VEN G S THROUGH YOU . -

Toadies Vaden Todd Lewis - Vocals, Guitar Clark Vogeler - Guitar Mark Reznicek – Drums Doni Blair - Bass

Toadies Vaden Todd Lewis - vocals, guitar Clark Vogeler - guitar Mark Reznicek – drums Doni Blair - bass “There’s a certain uneasiness to the Toadies,” says Vaden Todd Lewis, succinctly and accurately describing his band—quite a trick. The Texas band is, at its core, just a raw, commanding rock band. Imagine an ebony sphere with a corona that radiates impossibly darker, and a brilliant circular sliver of light around that. It’s nebulous, but strangely distinct—and, shall we say incorrect. Or, as Lewis says, “wrong.” “Things are done a little askew [in the Toadies],” he says, searching for the right words. “There’s just something wrong with it that’s just really cool… and unique in a slightly uncomfortable way.” This sick, twisted essence was first exemplified on the band’s 1994 debut, Rubberneck (Interscope). An intense, swirling vortex of guitar rock built around Lewis’s “wrong” songs—like the smash single “Possum Kingdom,” subject to as much speculation as what’s in the Pulp Fiction briefcase, it rocketed to platinum status on the strength of that and two other singles, “Tyler” and “Away.” Its success was due to the Toadies’ organic sound and all-encompassing style, which they aimed to continue on their next album. Perhaps in keeping with the uneasy vibe, that success didn’t translate to label support when the Toadies submitted their second album, Feeler. Perhaps aptly, things in general just went wrong. It was the classic, cruel story: the label didn’t ‘get’ it. “These were the songs we played live,” says Rez. “It was pretty eclectic… different styles of heavy rock music—some fast, heavy punk rock songs and some slower, kinda mid-tempo stuff. -

Jeremy Hammond from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Jeremy Hammond From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jeremy Hammond (born January 8, 1985) is a political hacktivist and Jeremy Hammond computer hacker from Chicago. He was convicted and sentenced[1] in November 2013 to 10 years in US Federal Prison for hacking the private intelligence firm Stratfor and releasing the leaks through the whistle-blowing website WikiLeaks.[2][3] He founded the computer security training website HackThisSite[4] in 2003.[5] Contents 1 Background 1.1 Childhood 1.2 Education 1.3 Music 1.4 Career 2 Activism 2.1 Computer security 3 Arrests and activist history 3.1 Marijuana arrests 3.2 RNC 2004 Born Jeremy Hammond 3.3 Occupy Wicker Park January 8, 1985 3.4 Anti-Nazi protesting Chicago, Illinois 3.5 Chicago Pride Parade 3.6 Protest Warrior Relatives Jason Hammond (twin 3.7 Protesting Holocaust denier David Irving brother) 3.8 Olympic protest Website freejeremy.net 3.9 Stratfor case 4 Support hackthissite.org 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Background Childhood Hammond was raised in the Chicago suburb of Glendale Heights, Illinois, with his twin brother Jason.[4][6] Hammond became interested in computers at an early age, programming video games in QBasic by age eight, and building databases by age thirteen.[4][7] As a student at Glenbard East High School in the nearby suburb of Lombard, Hammond won first place in a district-wide science competition for a computer program he designed.[4] Also in high school, he became a peace activist, organizing a student walkout on the day of the Iraq invasion and starting a student newspaper to oppose the Iraq War. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Becoming a Hacker: Demographic Characteristics and Developmental Factors

Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice & Criminology Becoming a Hacker: Demographic Characteristics and Developmental Factors Kevin F. Steinmetz1 1Kansas State University Published on: Aug 16, 2020 License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0) Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice & Criminology Becoming a Hacker: Demographic Characteristics and Developmental Factors ABSTRACT Hackers are not defined by any single act; they go through a process of development. Building from previous research and through ethnographic interviews and participant observation, the current analysis examines characteristics which may influence an individual’s development as a hacker. General demographic characteristics are analyzed, the participants’ school experiences are discussed, and perceived levels of parental support and influence are defined. Finally, descriptions of first exposures to technology, the concept of hacking, and the hacking community are presented. The study concludes with theoretical implications and suggestions for future research. Introduction As a concept, hacking is a contested issue. For some, the term is synonymous with computer intrusions and other forms of technological malfeasance (Wall, 2007). Others consider hacking to be broader, to include activities like open-source software programming, and hardware hacking, among actions (Coleman, 2012; Coleman, 2013; Söderberg, 2008). Some consider hacking along ethical divisions, most notably described as black hats and white hats or hackers versus crackers (Holt, 2009; Taylor, 1999). What has become clear about hacking in the decades since its inception among technology students at MIT in the 1950s and 1960s (Levy, 1986) is that it serves as a lightning rod that attracts cultural conflict and public concern. Part of the disagreement over hacking stems from media and social construction (Halbert, 1997; Hollinger, 1991; Skibell, 2002; Taylor, 1999; Yar, 2013). -

Hackthiszine4.Pdf

When I was a kid, hackers were criminals. Hackers were dreamers who saw through this world and its oppressive institutions. Hackers were brilliant maniacs who defined themselves against a system of capitalist relations, and lived their lives in opposition. Every aspect of the hack- er’s life was a tension towards freedom -- from creating communities that shared information freely, to using that information in a way that would strike out against this sti- filing world. When nobody understood how technology worked in the systems that surrounded us, hackers figured those systems out and exploited them to our advantage. Hackers were criminals, yes, but their crimes were defined by the laws of the institutions that they sought to destroy. While they were consistently portrayed as criminals by those in- stitutions, their true crimes were only those of curious- ity, freedom, and the strength to dream of a better world. Somewhere along the way the ruling class started pay- ing hackers to defend the very systems that they had so passionately attacked. Originally we took these jobs while smiling out of the corners of our mouths, think- ing that we were only tricking those in control. But at some point we tricked ourselves. Where power does not break you, it seduces you - and seduced by the si- ren song of commodity relations, we lost sight of our dreams and desires. Instead of striking out to create a new world, we found ourselves writing facial reconition software that sought to preserve this one at all costs. Today, the attempts at revival of hacker culture make hackers nothing more than mere hobbyists. -

Hacked: a Pedagogical Analysis of Online Vulnerability Discovery Exercises

HackEd: A Pedagogical Analysis of Online Vulnerability Discovery Exercises Daniel Votipka Eric Zhang and Michelle L. Mazurek Tufts University University of Maryland [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Hacking exercises are a common tool for security exercises provide the most effective learning, and researchers education, but there is limited investigation of how they teach do not have a broad view of the landscape of current exercises. security concepts and whether they follow pedagogical best As a step toward expanding this analysis, we review online practices. This paper enumerates the pedagogical practices of 31 popular online hacking exercises. Specifically, we derive a set hacking exercises to address two main research questions: of pedagogical dimensions from the general learning sciences and • RQ1: Do currently available exercises apply general educational literature, tailored to hacking exercises, and review pedagogical principles suggested by the learning sciences whether and how each exercise implements each pedagogical di- literature? If so, how are these principles implemented? mension. In addition, we interview the organizers of 15 exercises to understand challenges and tradeoffs that may occur when • RQ2: How do exercise organizers consider which princi- choosing whether and how to implement each dimension. ples to implement? We found hacking exercises generally were tailored to students’ To answer these questions we performed an in-depth qual- prior security experience and support learning by limiting extra- itative review of 31 popular online hacking exercises (67% neous load and establishing helpful online communities. Con- versely, few exercises explicitly provide overarching conceptual of all online exercises we identified). As part of our analysis, structure or direct support for metacognition to help students we completed a sample of 313 unique challenges from these transfer learned knowledge to new contexts. -

Order Form Full

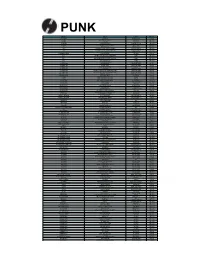

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS -

Surnames and National Identity in Turkey and Iran

Pisma Humanistyczne Zeszyt XIV z 2016 z ISSN 1506-9567 Pisma Humanistyczne Humanistyczne Pisma XIV IDENTITY Between unity and distinctiveness Pisma Humanistyczne Zeszyt XIV z 2016 z ISSN 1506-9567 Humanistic Scripts Volume XIV z 2016 z ISSN 1506-9567 IDENTITY Between unity and distinctiveness Scientific Council Chairman prof. zw. dr hab. Wiesław Kaczanowicz (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice) Members dr Mirosław Czerwiński (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice) dr hab. prof. UW Jarosław Czubaty (University of Warsaw) prof. Stéphane Guerard (Université Lille Nord de France) dr hab. prof. UŚ Mariusz Kolczyński (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice) dr hab. Irma Kozina (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice) dr hab. prof. UŚ Dariusz Kubok (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice) prof. zw. dr hab. Janusz Mucha (AGH University of Science and Technology) dr hab. prof. UŚ Dariusz Nawrot (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice) dr hab. Sławomir Raube (University of Białystok) prof. Reinhold Sackmann (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg) prof. dr hab. Robert Wiszniowski (University of Wrocław) dr hab. Piotr Wróblewski (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice) Editorial Staff mgr Tomasz Okraska (editor in chief) mgr Justyna Łapaj (deputy editor-in-chief, thematic editor: political science) mgr Maria Michniowska (thematic editor: sociology) mgr Agata Muszyńska (thematic editor: history) mgr Tomasz Pawlik (thematic editor: philosophy) mgr Iwona Bijak (Polish language editor) mgr Kamil Ciborowski (English language editor) mgr Emilia Woźniczko (technical editor) Reviewers Prof. dr hab. Anna Barska (University of Opole), dr hab. Agnieszka Chudzicka-Czupała (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice), dr hab. Tomasz Czakon (Univeristy of Silesia in Ka- towice), dr Paweł Ćwikła (Univeristy of Silesia in Katowice), dr hab.