Becoming a Hacker: Demographic Characteristics and Developmental Factors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeremy Hammond from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Jeremy Hammond From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jeremy Hammond (born January 8, 1985) is a political hacktivist and Jeremy Hammond computer hacker from Chicago. He was convicted and sentenced[1] in November 2013 to 10 years in US Federal Prison for hacking the private intelligence firm Stratfor and releasing the leaks through the whistle-blowing website WikiLeaks.[2][3] He founded the computer security training website HackThisSite[4] in 2003.[5] Contents 1 Background 1.1 Childhood 1.2 Education 1.3 Music 1.4 Career 2 Activism 2.1 Computer security 3 Arrests and activist history 3.1 Marijuana arrests 3.2 RNC 2004 Born Jeremy Hammond 3.3 Occupy Wicker Park January 8, 1985 3.4 Anti-Nazi protesting Chicago, Illinois 3.5 Chicago Pride Parade 3.6 Protest Warrior Relatives Jason Hammond (twin 3.7 Protesting Holocaust denier David Irving brother) 3.8 Olympic protest Website freejeremy.net 3.9 Stratfor case 4 Support hackthissite.org 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Background Childhood Hammond was raised in the Chicago suburb of Glendale Heights, Illinois, with his twin brother Jason.[4][6] Hammond became interested in computers at an early age, programming video games in QBasic by age eight, and building databases by age thirteen.[4][7] As a student at Glenbard East High School in the nearby suburb of Lombard, Hammond won first place in a district-wide science competition for a computer program he designed.[4] Also in high school, he became a peace activist, organizing a student walkout on the day of the Iraq invasion and starting a student newspaper to oppose the Iraq War. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Hackthiszine4.Pdf

When I was a kid, hackers were criminals. Hackers were dreamers who saw through this world and its oppressive institutions. Hackers were brilliant maniacs who defined themselves against a system of capitalist relations, and lived their lives in opposition. Every aspect of the hack- er’s life was a tension towards freedom -- from creating communities that shared information freely, to using that information in a way that would strike out against this sti- filing world. When nobody understood how technology worked in the systems that surrounded us, hackers figured those systems out and exploited them to our advantage. Hackers were criminals, yes, but their crimes were defined by the laws of the institutions that they sought to destroy. While they were consistently portrayed as criminals by those in- stitutions, their true crimes were only those of curious- ity, freedom, and the strength to dream of a better world. Somewhere along the way the ruling class started pay- ing hackers to defend the very systems that they had so passionately attacked. Originally we took these jobs while smiling out of the corners of our mouths, think- ing that we were only tricking those in control. But at some point we tricked ourselves. Where power does not break you, it seduces you - and seduced by the si- ren song of commodity relations, we lost sight of our dreams and desires. Instead of striking out to create a new world, we found ourselves writing facial reconition software that sought to preserve this one at all costs. Today, the attempts at revival of hacker culture make hackers nothing more than mere hobbyists. -

Hacked: a Pedagogical Analysis of Online Vulnerability Discovery Exercises

HackEd: A Pedagogical Analysis of Online Vulnerability Discovery Exercises Daniel Votipka Eric Zhang and Michelle L. Mazurek Tufts University University of Maryland [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Hacking exercises are a common tool for security exercises provide the most effective learning, and researchers education, but there is limited investigation of how they teach do not have a broad view of the landscape of current exercises. security concepts and whether they follow pedagogical best As a step toward expanding this analysis, we review online practices. This paper enumerates the pedagogical practices of 31 popular online hacking exercises. Specifically, we derive a set hacking exercises to address two main research questions: of pedagogical dimensions from the general learning sciences and • RQ1: Do currently available exercises apply general educational literature, tailored to hacking exercises, and review pedagogical principles suggested by the learning sciences whether and how each exercise implements each pedagogical di- literature? If so, how are these principles implemented? mension. In addition, we interview the organizers of 15 exercises to understand challenges and tradeoffs that may occur when • RQ2: How do exercise organizers consider which princi- choosing whether and how to implement each dimension. ples to implement? We found hacking exercises generally were tailored to students’ To answer these questions we performed an in-depth qual- prior security experience and support learning by limiting extra- itative review of 31 popular online hacking exercises (67% neous load and establishing helpful online communities. Con- versely, few exercises explicitly provide overarching conceptual of all online exercises we identified). As part of our analysis, structure or direct support for metacognition to help students we completed a sample of 313 unique challenges from these transfer learned knowledge to new contexts. -

Notes Cyber Crime 2.0: an Argument to Update the United States Criminal

NOTES CYBER CRIME 2.0: AN ARGUMENT TO UPDATE THE UNITED STATES CRIMINAL CODE TO REFLECT THE CHANGING NATURE OF CYBER CRIME CHARLOTTE DECKER∗ I. INTRODUCTION In 1945, two engineers at the University of Pennsylvania invented the first general-purpose electronic computing device—the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (“ENIAC”).1 The ENIAC was capable of 5000 simple calculations a second, yet it took up the space of an entire room, “weighed 30 tons, and contained over 18,000 vacuum tubes, 70,000 resistors, and almost 5 million hand-soldered joints.”2 This machine cost over $1 million dollars, equivalent to roughly $9 million today.3 Over the next thirty years integrated circuits shrunk, yielding microprocessors able ∗ Class of 2008, University of Southern California Gould School of Law; B.A. History and Markets/Management 2005, Duke University. I am especially grateful to Brian Hoffstadt for his keen guidance throughout the writing of this Note, and to the editors and staff of the University of Southern California Law Review for their hard work. I also would like to thank Gabriel Morgan for fostering a healthy sense of competition in law school and in life, and my parents and siblings for their support and encouragement. 1. See Kevin W. Richey, The ENIAC (1997), http://ei.cs.vt.edu/~history/ENIAC.Richey.HTML for a comprehensive account of the invention of the ENIAC. 2. Mark G. Tratos, Entertainment on the Internet: The Evolution of Entertainment Production, Distribution, Ownership, and Control in the Digital Age, 862 PLI/PAT 127, 155 (2006). 3. See OFFICE OF MGMT. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Extracting Actionable

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Extracting Actionable Information From Security Forums A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science by Joobin Gharibshah December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Professor Michalis Faloutsos, Chairperson Professor Vassilis Tsotras Professor Eamonn Keogh Professor Vagelis Hristidis Copyright by Joobin Gharibshah 2020 The Dissertation of Joobin Gharibshah is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Professor Michalis Faloutsos, for his patience, motivation ,and his continuous support throughout my graduate study. He has always supported me not only by providing a research assistantship but also academically and emotionally through the rough road to finish this thesis. He genuinely cares about me as his student and believes that I can succeed. Michalis was not only my academic advisor but also he was a great friend of mine who has been by my side to help in all the steps. My PhD life was a great opportunity for me to learn a lot from Michalis. I wish I could have graduated in a world without COVID19 so that I could tell Michalis all these in person. Kudos to Michalis the best advisor I could have had in my Ph.D. I am thankful for the committee members, Prof. Vassilis Tsotras, Prof. Eamonn Keogh, and Prof. Vagelis Hristidis for their constructive comments and inputs. Their comments helped me shape up my dissertation and the research topic. Also, I would like deeply thank Prof. Vagelis Papalexakis for his insightful comments in my research. -

Hackers Gonna Hack: Investigating the Effect of Group Processes and Social Identities Within Online Hacking Communities

Hackers gonna hack: Investigating the effect of group processes and social identities within online hacking communities Helen Thackray Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bournemouth University October 2018 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 1 2 Hackers gonna hack: Investigating the effect of group processes and social identities within online hacking communities Helen Thackray Abstract Hacking is an ethically and legally ambiguous area, often associated with cybercrime and cyberattacks. This investigation examines the human side of hacking and the merits of understanding this community. This includes group processes regarding: the identification and adoption of a social identity within hacking, and the variations this may cause in behaviour; trust within in the social identity group; the impact of breaches of trust within the community. It is believed that this research could lead to constructive developments for cybersecurity practices and individuals involved with hacking communities by identifying significant or influencing elements of the social identity and group process within these communities. For cybersecurity, the positive influence on individual security approaches after the hacker social identity adoption, and the subsequent in-group or out-group behaviours, could be adapted to improve security in the work place context. For individuals involved in the communities, an increase in the awareness of the potential influences from their adopted social identities and from other members could help those otherwise vulnerable to manipulation, such as new or younger members. -

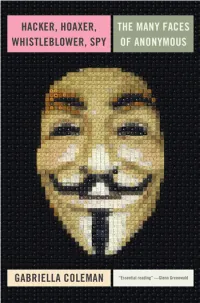

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

Introduction to Cybersecurity 4

First Edition: MAJ THOMAS A. OWENS, CAP 2019 Revision: MAJ DEREK RUSTVOLD, CAP DIRECTOR OF CYBER PROGRAMS, MID-ATLANTIC REGION Editing: SUSAN MALLETT, CAP NHQ DR. JEFF MONTGOMERY, CAP NHQ Published by NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS CIVIL AIR PATROL AEROSPACE EDUCATION DIRECTORATE MAXWELL AFB, ALABAMA 36112 REVISED SEPTEMBER 2019 Contents AN INTRODUCTION TO CYBERSECURITY 4 CAP Cybersecurity Module 4 Summary of Recent Attacks and Motivation for Action 5 Activity Group One: Codes, Ciphers and Encryption Awareness 8 Unit Profile: Room 40 and Bletchley Park 15 Biography: Alan Turing 15 CONCEPTS IN INFORMATION ASSURANCE AND CYBER WARFARE 16 Activity Group Two: Vulnerabilities and Basic Defense Skills 19 Patriot Bio: Maj. Gen. Robert J. Skinner 25 CONCEPTS OF OPERATING SYSTEMS AND NETWORKING 26 Activity Group Three: Basic Probing Skills 27 th Unit Profile: 24 Air Force 38 th Unit Profile: 67 Network Warfare Wing 38 Patriot Bio: Brig. Gen. Kevin B. Wooton 38 EXPLORING CAREERS IN CYBERSECURITY 39 Unit Profile: USCYBERCOM 43 Patriot Bio: General Keith B. Alexander 43 Bonus Graphic: USCYBERCOM 44 CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS 45 APPENDICES 51 A: Motivational Chronology of Cyber Warfare 51 B: Glossary of Terms, Threats, and Countermeasures 55 C: Toolbox of Promotional Resources 68 D: Toolbox of Technical Resources 72 E. Solutions to Module Activities 74 3 An Introduction to Cybersecurity Our Nation's Cyber Dependency At all its various levels, the United States has become a “cybernation.” Aviators will be amused to discover the prefix “cyber-” is derived from the word cybernetic, which comes from a Greek word κυβερνητικός (kybernētēs) which means pilot, rudder, steersman, or governor. -

Cisco Ironport Asyncos 6.5.0 for Web User Guide

™ IronPort AsyncOS 6.5 USER GUIDE for Web Security Appliances COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2010 by IronPort Systems®, Inc. All rights reserved. Part Number: 421-0172 Revision Date: September 15, 2010 The IronPort logo, IronPort Systems, SenderBase, and AsyncOS are all trademarks or registered trademarks of IronPort Systems, Inc. All other trademarks, service marks, trade names, or company names referenced herein are used for identification only and are the property of their respective owners. This publication and the information contained herein is furnished “AS IS” and is subject to change without notice. Publication of this document should not be construed as a commitment by IronPort Systems, Inc. IronPort Systems, Inc., assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or inaccuracies, makes no warranty of any kind with respect to this publication, and expressly disclaims any and all warranties of merchantability, fitness for particular purposes and non-infringement of third-party rights. Some software included within IronPort AsyncOS is distributed under the terms, notices, and conditions of software license agreements of FreeBSD, Inc., Stichting Mathematisch Centrum, Corporation for National Research Initiatives, Inc., and other third party contributors, and all such terms and conditions are incorporated in IronPort license agreements. The full text of these agreements can be found at https://support.ironport.com/3rdparty/AsyncOS_User_Guide-1- 1.html. Portions of the software within IronPort AsyncOS is based upon the RRDtool with the express written consent of Tobi Oetiker. IRONPORT SYSTEMS®, INC. CONTACTING IRONPORT CUSTOMER SUPPORT IronPort Systems, Inc. If you have purchased support directly from IronPort Systems, you 950 Elm Ave. can request our support by phone, email or online 24 hours a day, 7 San Bruno, CA 94066 days a week. -

![Hack This Zine Into Other Languages, If You Are Inter- Ested Send an Email to Staff [At] Hackbloc [Dot] Org](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7669/hack-this-zine-into-other-languages-if-you-are-inter-ested-send-an-email-to-staff-at-hackbloc-dot-org-6707669.webp)

Hack This Zine Into Other Languages, If You Are Inter- Ested Send an Email to Staff [At] Hackbloc [Dot] Org

The Hacktivist’s Guide To The Internet Page 1 HTZ Issue 9, Winter 2010 The Hacktivist’s Guide To The Internet ================================================================== THE HACKTIVIST’S GUIDE TO THE INTERNET (HackThisZine #9, Winter 2010) ================================================================== Introduction....................................................................................................................Page 03 News and Events Pirate Bay Launches Private Proxy (VPN) Services.....................................................Page 05 Hate Social Networking?...............................................................................................Page 06 German ‘Fleshmob’ Takes on Full-Body Airport Scanners...........................................Page 06 Anonymous Pwns Australian Government in Operation Titstorm................................Page 07 Fugitive VoIP Hacker Pleads Guilty to Stealing 10 Million Minutes............................Page 07 Manchester Police Computer Systems Shut Down by Conficker..................................Page 08 Even if you clear your private data, how track able is your browser.............................Page 08 See You in the Bay!........................................................................................................Page 08 Theory Social Change Within The Hacker Movement... By Dave U. Random.........................Page 11 Autonomy and a New High Tech by Cloacina...............................................................Page 13 Can’t Stop -

1 Countermeasures: an Interactive

CounterMeasures: An Interactive Game for Security Training A Major Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Computer Science and Interactive Media and Game Development by Craig Jordan _____________________________ Matt Knapp _____________________________ Dan Mitchell _____________________________ Date: March 2011 Approved: ______________________________________ Prof. Mark Claypool, Co-Advisor ______________________________________ Prof. Kathi Fisler, Co-Advisor 1 Abstract: Computer security has become vital for protecting users, applications and data from harm. However, the United States is facing a severe deficit in the number of security professionals needed to adequately protect our computer systems. Often learning practical knowledge about computer security from textbooks and academic papers is less engaging and more time consuming then through simulations or games. Our hypothesis is that participating in a training simulation that closely emulates real-world systems is a better platform for learning security concepts than reading about security concepts in technical documents. The purpose of this MQP is to test our hypothesis through a game, called CounterMeasures, that teaches the basics of computer security. CounterMeasures provides the user with a real, interactive shell with which to practice security skills and challenges that are outlined through a series of objectives and help screens. The CounterMeasures architecture is client-server based, with the client utilizing Adobe Flex and AIR, and the server consisting of BlazeDS, which uses a Tomcat webserver. The client connects via ssh to the virtual machine on the server after pulling the user information from a database. This ssh connection allows the user to interact with the machine and run commands, while the client displays the terminal responses, as well as their objectives and help screens.