Eytan 20 Jun 1990 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi V. Migdal Cooperative Village 1

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi v. Migdal Cooperative Village 1 CA 6821/93 LCA 1908/94 LCA 3363/94 United Mizrahi Bank Ltd. v. 1. Migdal Cooperative Village 2. Bostan HaGalil Cooperative Village 3. Hadar Am Cooperative Village Ltd 4. El-Al Agricultural Association Ltd. CA 6821/93 1. Givat Yoav Workers Village for Cooperative Agricultural Settlement Ltd 2. Ehud Aharonov 3. Aryeh Ohad 4. Avraham Gur 5. Amiram Yifhar 6. Zvi Yitzchaki 7. Simana Amram 8. Ilan Sela 9. Ron Razon 10. David Mini v. 1. Commercial Credit Services (Israel) Ltd 2. The Attorney General LCA 1908/94 1. Dalia Nahmias 2. Menachem Nahmias v. Kfar Bialik Cooperative Village Ltd LCA 3363/94 The Supreme Court Sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals [November 9, 1995] Before: Former Court President M. Shamgar, Court President A. Barak, Justices D. Levine, G. Bach, A. Goldberg, E. Mazza, M. Cheshin, Y. Zamir, Tz. E Tal Appeal before the Supreme Court sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals 2 Israel Law Reports [1995] IsrLR 1 Appeal against decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) on 1.11.93 in application 3459/92,3655, 4071, 1630/93 (C.F 1744/91) and applications for leave for appeal against the decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) dated 6.3.94 in application 5025/92 (C.F. 2252/91), and against the decision of the Haifa District Court (Judge S. Gobraan), dated 30.5.94 in application for leave for appeal 18/94, in which the appeal against the decision of the Head of the Execution Office in Haifa was rejected in Ex.File 14337-97-8-02. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

WATCHING THE WAR AND KEEPING THE PEACE: THE UNITED NATIONS TRUCE SUPERVISION ORGANIZATION (UNTSO) IN THE MIDDLE EAST, 1949-1956 by Andrew Gregory Theobald A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (May, 2009) Copyright ©Andrew Gregory Theobald, 2009 Abstract By virtue of their presence, observers alter what they are observing. Yet, the international soldiers of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) did much more than observe events. From August 1949 until the establishment of the United Nations Emergency Force in November 1956, the Western military officers assigned to UNTSO were compelled to take seriously the task of supervising the Arab-Israeli armistice, despite the unwillingness of all parties to accept an actual peace settlement. To the extent that a particular peacekeeping mission was successful – i.e., that peace was “kept” – what actually happened on the ground is usually considered far less important than broader politics. However, as efforts to forge a peace settlement failed one after another, UNTSO operations themselves became the most important mechanism for regional stability, particularly by providing a means by which otherwise implacable enemies could communicate with each other, thus helping to moderate the conflict. This communication played out against the backdrop of the dangerous early days of the Cold War, the crumbling of Western empires, and the emergence of the non- aligned movement. Analyses of the activities of the Mixed Armistice Commissions (MACs), the committees created to oversee the separate General Armistice Agreements signed between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, particularly those during the 1954 to 1956 tenure as UNTSO chief of staff of Canadian Major-General E.L.M. -

Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS)

P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS) The purpose of the Jaffee Center is, first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel's national security as well as Middle East regional and international secu- rity affairs. The Center also aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are - or should be - at the top of Israel's national security agenda. The Jaffee Center seeks to address the strategic community in Israel and abroad, Israeli policymakers and opinion-makers and the general public. The Center relates to the concept of strategy in its broadest meaning, namely the complex of processes involved in the identification, mobili- zation and application of resources in peace and war, in order to solidify and strengthen national and international security. To Jasjit Singh with affection and gratitude P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Memorandum no. 55, March 2000 Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies 6 P. R. Kumaraswamy Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv, 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel Tel. 972 3 640-9926 Fax 972 3 642-2404 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.tau.ac.il/jcss/ ISBN: 965-459-041-7 © 2000 All rights reserved Graphic Design: Michal Semo Printed by: Kedem Ltd., Tel Aviv Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations 7 Contents Introduction .......................................................................................9 -

Israel and Turkey: from Covert to Overt Relations

Israel and Turkey: From Covert to Overt Relations by Jacob Abadi INTRODUCTION Diplomatic relations between Israel and Turkey have existed since the Jewish state came into being in 1948, however, they have remained covert until recently. Contacts between the two countries have continued despite Turkey's condemnation of Israel in the UN and other official bodies. Frequent statements made by Turkish officials regarding the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Palestinian dilemma give the impression that Turco-Israeli relations have been far more hostile than is actually the case. Such an image is quite misleading, for throughout the years political, commercial, cultural and even military contacts have been maintained between the two countries. The purpose of this article is to show the extent of cooperation between the two countries and to demonstrate how domestic as well as external constraints have affected the diplomatic ties between them. It will be argued that during the first forty years of Israel's existence relations between the two countries remained cordial. Both sides kept a low profile and did not reveal the nature of these ties. It was only toward the end of the 1980s, when the international political climate underwent a major upheaval, that the ties between the two countries became official and overt. Whereas relations with Israel constituted a major problem in Turkish diplomacy, Israeli foreign policy was relatively free from hesitations and constraints. For Israeli foreign policy makers it was always desirable to establish normal relations with Turkey, whose location on the periphery of the Middle East gave it great strategic importance. -

Policy Strategies of Accommodation Or Domination in Jerusalem: an Historical Perspective Ira D

Document generated on 09/25/2021 1:08 p.m. Journal of Conflict Studies Policy Strategies of Accommodation or Domination in Jerusalem: An Historical Perspective Ira D. Sharkansky Volume 15, Number 1, Spring 1995 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs15_01art05 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Sharkansky, I. D. (1995). Policy Strategies of Accommodation or Domination in Jerusalem:: An Historical Perspective. Journal of Conflict Studies, 15(1), 74–91. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Policy Strategies of Accommodation or Domination in Jerusalem: An Historical Perspective by Ira Sharkansky Ira Sharkansky is Professor of Political Science and Public Administration at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. With an age of some 4.000 years, Jerusalem is one of the world's oldest cities. Although there have been numerous changes in regime, prominent issues confronting the present city resemble those of times past, and certain continuities can be found in the policy strategies pursued by those who have governed Jerusalem. This article compares the strategy of the present regime with those apparent in previous periods from the sixth century BC. -

The Holocaust: Factor in the Birth of Israel? by Evyatar Friesel

The Holocaust: Factor in the Birth of Israel? by Evyatar Friesel It is widely believed that the catastrophe of European Jewry during World War II had a decisive influence on the establishment of the Jewish state in 1948. According to this thesis, for the Jews the Holocaust triggered a supreme effort toward statehood, based on the understanding that only a Jewish state might again avoid the horrors of the 1940s. For the nations of the world, shocked by the horror of the extermination and burdened by feelings of guilt, the Holocaust convinced them that the Jews were entitled to a state of their own. All these assumptions seem extremely doubtful. They deserve careful re-examination in light of the historical evidence. Statehood in Zionist Thought The quest for a Jewish state had always been paramount in Zionist thought and action. For tactical reasons official Zionism was cautious in explaining its ultimate aims, especially when addressing general public opinion. Terms other than "state" were used in various political documents or official utterances by leading Zionist statesmen: Jewish home, Jewish National Home, commonwealth, Jewish commonwealth. But there is no reason to doubt that the ultimate aim of the Zionist mainstream was the creation of a state in Palestine. The question remained as to what methods should be used in order to reach the consummation of these hopes. One possibility was the evolutionary path, implied also in the political relations between the Zionists and leading British statesmen between 1917 and 1920. It found implicit expression in the terms and the structure of the Palestine Mandate approved by the League of Nations in July 1922. -

The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table

The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table Dan Zafrir THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS Every academic year ICSR is offering six young leaders from Israel and Palestine the opportunity to come to London for a period of two months in order to develop their ideas on how to further mutual understanding in their region through addressing both themselves and “the other”, as well as engaging in research, debate and constructive dialogue in a neutral academic environment. The end result is a short paper that will provide a deeper understanding and a new perspective on a specific topic or event that is personal to each Fellow. Author: Dan Zafrir, 2017 Through the Looking Glass Fellow, ICSR. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. Editor: Katie Rothman, ICSR CONTACT DETAILS Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. For questions, queries and additional copies of the report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 (0)20 7848 2065 E. [email protected] For news and updates, follow ICSR on Twitter: @ICSR_Centre. © ICSR 2017 The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table Contents Introduction 3 Empathy Starts with the Self 4 The Opening of the Israeli Mind… 5 … And the Closing of the Palestinian One 7 Empathizing with the Past to Establish a Future (i.e.: Policy Recommendations) 8 Conclusion 9 Reference List 10 1 The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table 2 The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table Introduction mpathy is often regarded as a key feature of social life. -

My Life's Story

My Life’s Story By Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz 1915-2000 Biography of Lieutenant Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Z”L , the son of Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Shwartz Z”L , and Rivka Shwartz, née Klein Z”L Gilad Jacob Joseph Gevaryahu Editor and Footnote Author David H. Wiener Editor, English Edition 2005 Merion Station, Pennsylvania This book was published by the Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Memorial Committee. Copyright © 2005 Yona Shwartz & Gilad J. Gevaryahu Printed in Jerusalem Alon Printing 02-5388938 Editor’s Introduction Every Shabbat morning, upon entering Lower Merion Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation on the outskirts of the city of Philadelphia, I began by exchanging greetings with the late Lt. Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz. He used to give me news clippings and booklets which, in his opinion, would enhance my knowledge. I, in turn, would express my personal views on current events, especially related to our shared birthplace, Jerusalem. Throughout the years we had an unwritten agreement; Eliyahu would have someone at the Israeli Consulate of Philadelphia fax the latest news in Hebrew to my office (Eliyahu had no fax machine at the time), and I would deliver the weekly accumulation of faxes to his house on Friday afternoons before Shabbat. This arrangement lasted for years. Eliyahu read the news, and distributed the material he thought was important to other Israelis and especially to our mutual friend Dr. Michael Toaff. We all had an inherent need to know exactly what was happening in Israel. Often, during my frequent visits to Israel, I found that I was more current on happenings in Israel than the local Israelis. -

Purely Commentary

Purely Commentary 'Hooligans Attacking Tunis Jews Condemned by Bourgutha President Habib Bourguiba appeared on Tunisian radio and television Monday to LONDON — on Tunisian Jews and Jewish property stemming from the Arab- By Philip Slomovitz issue a stern warning against attacks Israeli war, it was reported here Tuesday from Tunis. orders that they The Emergency: A Jewish as Well as Israeli Issue The Tunisian president denounced the incidents and gave that all such demonstrations would be halted "by every means That which is happening on Israel's borders is not a must cease, adding available in the power of the state." mere Israeli issue. It is an emergency situation for the The World Jewish Congress office here sent a cable of appreciation Tuesday entire Jewish people and all of Jewry is under threat. to President Bourguiba for his condemnation of "outrages committed against your So many lies have been uttered and will be repeated at Jewish citizens who rely for protection on your sense of justice, as demonstrated by the United Nations, in the press, on public platforms, brand- your intention to punish all culprits." The Tunisian government formally apologized Tuesday to the Tunisian Jewish ing Israel as an aggressor, that a great responsibility devolves community and said that the hooligans" who sacked the Jewish quarter in Tunis upon Jews everywhere not to be misled by falsified reports, Monday did not represent the Tunisian people or government. Special police units to beware of misrepresentations, to be on guard lest the section to guard it. entire Jewish people once again is subjected to the vilest Bourguiba were detailed to the calumnies as a result of blunders by world powers which • have led to the new dangers confronting Israel. -

'Mowing the Grass': Israel'sstrategy for Protracted Intractable Conflict

This article was downloaded by: [Bar-Ilan University] On: 27 February 2014, At: 05:21 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Strategic Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjss20 ‘Mowing the Grass’: Israel’s Strategy for Protracted Intractable Conflict Efraim Inbara & Eitan Shamira a Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University, Israel Published online: 10 Oct 2013. To cite this article: Efraim Inbar & Eitan Shamir (2014) ‘Mowing the Grass’: Israel’s Strategy for Protracted Intractable Conflict, Journal of Strategic Studies, 37:1, 65-90, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2013.830972 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2013.830972 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The IDF in the Second Intifada

Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade |Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | Shiri Tal-Landman המכון למחקרי ביטחון לאומי THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURcITY STUDIES INCORPORATING THE JAFFEE bd CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 CONteNts Abstracts | 3 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | 7 Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | 27 Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | 39 Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | 49 Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | 63 Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | 71 Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | 85 Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | 101 Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade | 123 Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | 133 Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | 141 Shiri Tal-Landman The purpose of Strategic Assessment is to stimulate and Strategic enrich the public debate on issues that are, or should be, ASSESSMENT on Israel’s national security agenda. -

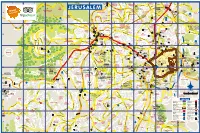

Jerusalem-Map.Pdf

H B S A H H A R ARAN H A E K A O RAMOT S K R SQ. G H 1 H A Q T V V HI TEC D A E N BEN G GOLDA MEIR I U V TO E R T A N U H M HA’ADMOR ESHKOL E 1 2 3 R 4 5 Y 6 DI ZAHA 7 MA H 8 E Z K A 9 INTCH. T A A MEGUR A E AR I INDUSTRY M SANHEDRIYYA GIV’AT Z L LOH T O O T ’A N Y A O H E PARA A M R N R T E A O 9 R (HAR HOZVIM) A Y V M EZEL H A A AM M AR HAMITLE A R D A A MURHEVET SUF I HAMIVTAR A G P N M A H M ET T O V E MISHMAR HAGEVUL G A’O A A N . D 1 O F A (SHAPIRA) H E ’ O IRA S T A A R A I S . D P A P A M AVE. Lev LEHI D KOL 417 i E V G O SH sh E k Y HAR O R VI ol L O I Sanhedrin E Tu DA M L AMMUNITION n n N M e E’IR L Tombs & Garden HILL l AV 436 E REFIDIM TAMIR JERUSALEM E. H I EZRAT T N K O EZRAT E E AV S M VE. R ORO R R L HAR HAMENUHOT A A A T E N A Z ’ Ammunition I H KI QIRYAT N M G TORA O 60 British Military (JEWISH CEMETERY) E HASANHEDRIN A N Hill H M I B I H A ZANS IV’AT MOSH H SANHEDRIYYA Cemetery QIRYAT SHEVA E L A M D Y G U TO MEV U S ’ L C E O Y M A H N H QIRYAT A IKH E .