Beyond Fossil Fuels: November 2019 Vibhuti Garg Fiscal Transition in BRICS Anna Geddes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India: Inventory of Estimated Budgetary Support and Tax Expenditures for Fossil-Fuels

INDIA: INVENTORY OF ESTIMATED BUDGETARY SUPPORT AND TAX EXPENDITURES FOR FOSSIL-FUELS Energy resources and market structure India is one of the fastest growing energy markets in the world. The country is the world’s third largest coal producer owing to its large deposits. Coal is the leading primary fuel in India’s energy mix, accounting for 44% of the country’s total primary energy supply (TPES), with thermal power plants making up the majority of coal consumption. Biomass accounts for 25% of total energy use, followed by oil and natural gas, which account respectively for 22% and 7% of the country’s energy needs. Remaining energy sources, such as nuclear power and hydro-electricity, account for about 1% each. The country’s proven reserves of oil were 5.5 billion barrels as of December 2012; nonetheless, domestic production falls far short of domestic demand and the country depends heavily on imported crude oil. The state-owned coal company, Coal India Limited (CIL), retains a near monopoly of coal extraction, with over 90% of domestic coal extraction attributed to government-controlled mines. Most coal mining occurs in the states of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and West Bengal. Market reforms are being implemented to bring competition and transparency to the coal sector. The government has been grappling to get an effective regulatory framework in place, which includes the loosening of regulations for the coal industry, with the objective of moving some grades of coal closer to international market prices, and allocating additional coal blocks through a transparent open bidding process. -

“Power Finance Corporation - Investors Interaction Meet”

“Power Finance Corporation - Investors Interaction Meet” May 31, 2018 MANAGEMENT: TEAM OF POWER FINANCE CORPORATION:- - Mr. Rajeev Sharma - Chairman and Managing Director - Mr. D. Ravi - Director (Commercial) - Mr. C. Gangopadhyay - Director (Project) - Shri Sitaram Pareek - Independent Director Page 1 of 23 Power Finance Corporation May 31, 2018 Speaker: Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen. On behalf of Power Finance Corporation, we feel honored and privileged to welcome you all to this Investors Interaction Meet. The company recently announced its financial results for the year 2017-18 and has been successful in maintaining its growth trajectory. PFC is always aiming to connect with its investor and build a strong and enduring positive relationship with the investment community. With this objective, today’s event has been organized to discuss PFC’s current performance and future outlook with the current and prospective investors. On the desk in the center is Chairman and Managing Director -- Shri Rajeev Sharma along with the other directors. To my immediate left is Shri DRavi – Director, Commercial. Next to him is Shri C Gangopadhyay – Director, Projects. To my extreme left is Shri Sitaram Pareek – Independent Director and beside him is Shri N.B. Gupta – Director, Finance. They are all in front of you to give a brief insight of PFC’s performance during the financial year 2017-18. They will also present to you a roadmap for the forthcoming year. I request Shri Rajeev Sharma -- Chairman and Managing Director to address the gathering. Rajeev Sharma: Thank you very much for sparing your valuable time to be present here during this interaction. -

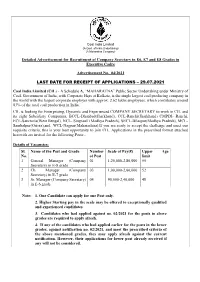

Detailed Advertisement for Recruitment of Company Secretary in E6, E7 and E8 Grades in Executive Cadre

Coal India Limited (A Govt. of India Undertaking) (A Maharatna Company) Detailed Advertisement for Recruitment of Company Secretary in E6, E7 and E8 Grades in Executive Cadre Advertisement No. 04/2021 LAST DATE FOR RECEIPT OF APPLICATIONS – 29.07.2021 Coal India Limited (CIL) - A Schedule A, “MAHARATNA” Public Sector Undertaking under Ministry of Coal, Government of India, with Corporate Hqrs at Kolkata, is the single largest coal producing company in the world with the largest corporate employer with approx. 2.62 lakhs employees, which contributes around 83% of the total coal production in India. CIL is looking for Enterprising, Dynamic and Experienced COMPANY SECRETARY to work in CIL and its eight Subsidiary Companies, BCCL-Dhanbad(Jharkhand), CCL-Ranchi(Jharkhand) CMPDI- Ranchi, ECL-Sanctoria(West Bengal), NCL- Singrauli (Madhya Pradesh), SECL-Bilaspur(Madhya Pradesh), MCL- Sambalpur(Orissa),and WCL-Nagpur(Maharashtra).If you are ready to accept the challenge and meet our requisite criteria, this is your best opportunity to join CIL. Applications in the prescribed format attached herewith are invited for the following Posts:- Details of Vacancies: Sl. Name of the Post and Grade Number Scale of Pay(₹) Upper Age No. of Post limit 1 General Manager (Company 01 1,20,000-2,80,000 55 Secretary) in E-8 grade 2 Ch. Manager (Company 03 1,00,000-2,60,000 52 Secretary) in E-7 grade 3 Sr. Manager (Company Secretary) 04 90,000-2,40,000 48 in E-6 grade Note- 1. One Candidate can apply for one Post only. 2. Higher Starting pay in the scale may be offered to exceptionally qualified and experienced candidates. -

Ngo Documents 2013-08-14 00:00:00 Coal India Investor Brief High Risk

High risk, low return COAL INDIA LTD’s shareholder value is threatened by poor corporate governance, faulty reserve estimations, regulatory risk and macro-economic issues. Introduction Coal India Limited is the world’s largest coal miner, with a production of 435 million metric tons (MT) in 2011 -201 2. There is significant pressure on CIL to deliver annual production growth rates in excess of 7%. The company has a 201 7 production target of 61 5 MT.[1 ] Coal India’s track record raises questions over its ability to deliver this rate of growth. In addition, serious governance issues are likely to impact CIL’s financial performance. These pose a financial and reputational risk to CIL, its shareholders and lenders, while macro- economic issues in the Indian energy economy pose a long term threat to Coal India. • CIL’s attempts to access new mining areas are facing widespread opposition from local communities and environmental groups. With its reliance on open-pit mining, access to new mines are essential for CIL to achieve production targets. G • CIL has grown reliant on shallow, open pit mining for 90% of its production, and has lost in-house expertise on deep mining techniques. N I • CIL has a record of poor corporate governance, manifested in rampant corruption, poor worker safety and repeated legal violations. This has, in the last year alone, led to penalties and F closure notices for over 50 mines, threatening both its financial performance and reputation. E I • CIL’s financial performance has been affected by directives from majority shareholder Government of India to keep coal prices artifically low.[2] According to one estimate, this cost R CIL $1 .75 billion in the 201 2-1 3 financial year alone.[3] The government has also taken away coal blocks allocated to CIL and given them to private players.[4] B • Changing economics of coal power in India; renewable energies are becoming cost- competitive even as coal faces increased regulatory scrutiny and public opposition. -

G20 Subsidies to Oil, Gas and Coal Production

G20 subsidies to oil gas and coal production: India Vibhuti Garg and Ken Bossong Argentina Australia Brazil Canada China France Germany India Indonesia Italy Japan Korea (Republic of) Mexico Russia Saudi Arabia This country study is a background paper for the report Empty promises: G20 subsidies South Africa to oil, gas and coal production by Oil Change International (OCI) and the Overseas Turkey Development Institute (ODI). It builds on research completed for an earlier report The fossil United Kingdom fuel bailout: G20 subsidies to oil, gas and coal exploration, published in 2014. United States For the purposes of this country study, production subsidies for fossil fuels include: national subsidies, investment by state-owned enterprises, and public finance.A brief outline of the methodology can be found in this country summary. The full report provides a more detailed discussion of the methodology used for the country studies and sets out the technical and transparency issues linked to the identification of G20 subsidies to oil, gas and coal production. The authors welcome feedback on both this country study and the full report to improve the accuracy and transparency of information on G20 government support to fossil fuel production. A Data Sheet with data sources and further information for India’s production subsidies is available at: http://www.odi.org/publications/10073-g20-subsidies-oil-gas-coal-production-india priceofoil.org Country Study odi.org November 2015 Background remained substantial at $11 billion in 2014–15 (MoPNG, India has substantial fossil fuel reserves, including 61 2015b). Similar consumer subsidies of approximately billion tonnes of coal, 5.7 billion barrels of oil and 1.4 $12 billion in 2012–13 existed in the electricity sector. -

1 Objectives, Functions, Schemes and Organizational Structure

1 Objectives, Functions, Schemes and Organizational Structure The core objectives of MoC are linked to its vision of securing the availability of coal to meet the demand of different sectors of the economy in an eco-friendly and sustainable manner and the overall mission of augmenting production through Government companies as well as the captive mining route by adopting state-of-the-art, clean-coal technologies; enhancing exploration efforts with thrust on increasing proven resources and developing the necessary infrastructure for prompt evacuation of coal. 1.1 Objectives Ensuring achievement of Annual Action Plan targets for coal production and off-take, OBR removal, lignite production and lignite based power generation. Infrastructure development to augment coal and washed coal production. Leveraging technology to minimize environmental externalities. Cutting edge research and development initiatives. Enhancing exploration to augment resource base. Quality and reliability in customer services. Expeditious and joint solutions to inter-ministerial issues. Improving efficiency of Coal India Attracting private investments Allocating new coal blocks in a transparent manner. 1.2 Functions Facilitating exploration, development and exploitation of coking and non-coking coal and lignite reserves in India. All matters related to production, supply, distribution and prices of coal. 3 Development and operation of coal washeries other than those for which Department of Steel is responsible. Administration of the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) -

Coal India Signs Mou with GAIL

Monthly Magazine on CPSE happenings March, 2020 | www.psuconnect.in The Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi interacting with the Heads of Indian Missions abroad through video conferencing to discuss responses to the global COVID-19 pandemic www.psuconnect.in March, 2020 1 EVENTS Monthly Magazine of CPSE happenings WINGS INDIA 2020 takes off hri K.T Rama Rao, Minister for Industries &Commerce,Telangana inaugurated Wings India 2020,at Begumpet Airport, Hyderabad in presence of Shri M K Rao, Minister of Civil Aviation, Puducherry, Shri Arvind Singh, Chairman, AAI and Smt Usha SPadhee, Joint Secretary, Minister of Civil Aviation, GoI. The international event is jointly organized by Ministry of Civil Aviation, Govt. of India, AAI and FICCI. www.psuconnect.in March, 2020 2 EVENTS Monthly Magazine of CPSE happenings Shri Rajnath Singh Inaugurates Shri R.K Singh inaugurates NTPC PFCSetupFirstWomens The Light Combat Helicopter O&M-IPS 2020 Conference ConvenienceLoungeAt nion Defence Minister, Shri Rajnath Singh inaugurates the Light Combat DelhiMetrosBlueLine UHelicopter Final Assembly Hangar at the hri S N Sahai, Secretary, Power in Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) Complex the presence of CMD/PFC Shri in Bengaluru. SRajeev Sharma and MD/DMRC Dr HAL is actively engaged and is contributing to Mangu Singh and inaugurated the the space programmes of the country. HAL is Women's Convenience Lounge at also setting up dedicated facility for Barakhamba Road station with a dedicated manufacture of cryogenic engines. diaper changing centre, breastfeeding kiosk & free napkin vending machine. hri R K Singh, Union Minister of State with Independent Charge for Power and New & SRenewable Energy, Inaugurated the 9th edition of NTPC O&M-India Power Station (IPS) 2020 conference at Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyay auditorium in Raipur. -

Unpublished Decision Memorandum

A-570-898 AR 06/01/2007-05/31/2008 Public Document IA/NME Unit: JCM/BMP MEMORANDUM TO: Carole A. Showers Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary for Import Administration FROM: John M. Andersen Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations SUBJECT: Issues and Decision Memorandum for the 2007 – 2008 Administrative Review of Chlorinated Isocyanurates from the People’s Republic of China SUMMARY: We have analyzed the case and rebuttal briefs of interested parties in the antidumping duty administrative review of chlorinated isocyanurates from the People’s Republic of China. The period of review is June 1, 2007, through May 31, 2008. As a result of our analysis, we have made changes, including corrections of certain inadvertent programming and clerical errors, in the margin calculation. We recommend that you approve the positions described in the “Discussion of the Issues” section of this memorandum. Below is the complete list of the issues for which we received comments and rebuttal comments by the parties: Surrogate Values Comment 1: Surrogate Value for Urea Comment 2: Surrogate Value for Steam Coal Comment 3: Financial Ratios Comment 4: Surrogate Value for Anhydrous Ammonia Company Specific Issues Comment 5: Clerical Error – By Product Offset LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS The Act Tariff Act of 1930, as amended AUV Average Unit Value Bihar Bihar Caustic & Chemicals Limited CAFC Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit CIL Coal India Limited CIT Court of International Trade The Department Department of Commerce FOP Factors of Production IBM Indian Bureau of Mines ITC International Trade Commission Jiheng Hebei Jiheng Chemical Corporation, Ltd. -

India Coal Mine Methane Market Study

India Coal Mine Methane Market Study EPA Publication No: 456R19001 May 2019 Disclaimer This publication was developed at the request of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), in support of the Global Methane Initiative (GMI). In collaboration with the Coalbed Methane Outreach Program (CMOP), Advanced Resources International, Inc. (ARI) authored this report under RTI International contract EP-BPA-18-H-0010. This report was prepared for the USEPA. This analysis uses publicly available information in combination with information obtained through direct contact with mine personnel, equipment vendors, and project developers. USEPA does not: a) make any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the information contained in this report, or that the use of any apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report may not infringe upon privately owned rights; b) assume any liability with respect to the use of, or damages resulting from the use of, any information, apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report; nor c) imply endorsement of any technology supplier, product, or process mentioned in this report. India Market Study Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 India’s Coal Mining Industry ............................................................................................. 3 2.1 India’s Growing Energy Deficit and the -

138 Coal India Limited

CONTENT Member of the Board 05 Management During 2017-2018 06 Banker, Auditors and Corporate Office 07 Chairman’s Statement 08 Performance of CIL at a glance 12 (Graphical Representation) Operation Statistics 17 Brief Profile of Directors 32 Director’s Report 38 Comments of the Comptroller & Auditor General of India on Standalone Accounts of Coal India Limited 86 Auditor Report on the Standalone Financial Statements for the year ended 31st March 2018 88 Comments of the Comptroller & Auditor General of India on Consolidated Accounts of Coal India Limited 94 Auditor Report on the Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended 31st March 2018 96 Observation of Auditor on Standalone Financial Statements and Management Explanation 103 Observation of Auditor on Consolidated Financial Statements and Management Explanation 106 Secretarial Auditor Report 145 Report on Corporate Governance 163 Sustainable Development Report 181 Management Discussion and Analysis Report 182 Standalone Accounts of CIL 205 Consolidated Accounts of CIL & its Subsidiaries 269 GREEN INITIATIVE IN CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Dear Shareholder, Pursuant to the initiatives undertaken by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, encouraging the companies to reduce the carbon footprint by enabling them to send the Annual Report etc to the Shareholders through electronic mode, your company has already taken the following steps:- Emails have been sent to all shareholders who have not exercised the option to receive the Annual Report 2017-18 in physical mode. They have been provided with a link (URL) to the website of COAL INDIA LIMITED for downloading the Annual Report 2017-18. For members who have not registered their email addresses, physical copy of Annual Report 2017-18 is being sent by the permitted mode. -

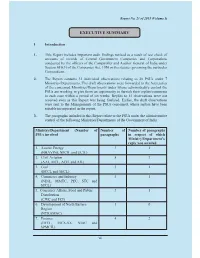

Executive Summary

Report No. 21 of 2015 (Volume I) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I Introduction 1. This Report includes important audit findings noticed as a result of test check of accounts of records of Central Government Companies and Corporations conducted by the officers of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India under Section 619(3) of the Companies Act, 1956 or the statutes governing the particular Corporations. 2. The Report contains 31 individual observations relating to 28 PSUs under 7 Ministries/Departments. The draft observations were forwarded to the Secretaries of the concerned Ministries/Departments under whose administrative control the PSUs are working to give them an opportunity to furnish their replies/comments in each case within a period of six weeks. Replies to 15 observations were not received even as this Report was being finalised. Earlier, the draft observations were sent to the Managements of the PSUs concerned, whose replies have been suitable incorporated in the report. 3. The paragraphs included in this Report relate to the PSUs under the administrative control of the following Ministries/Departments of the Government of India: Ministry/Department (Number of Number of Number of paragraphs PSUs involved paragraphs in respect of which Ministry/Department’s reply was awaited 1. Atomic Energy 3 1 (BHAVINI, NPCIL and UCIL) 2. Civil Aviation 8 7 (AAI, AICL, ACIL and AIL) 3. Coal 3 1 (BCCL and SECL) 4. Commerce and Industry 5 1 (NINL, MMTC, PEC, STC and STCL) 5. Consumer Affairs, Food and Public 5 1 Distribution (CWC and FCI) 6. Development of North Eastern 1 0 Region (NERAMAC) 7. -

DISCUSSION PAPER COAL TRANSITION in INDIA Thomas Spencer, Raghav Pachouri, G Renjith, Sachi Vohra, TERI

DISCUSSION PAPER COAL TRANSITION IN INDIA Thomas Spencer, Raghav Pachouri, G Renjith, Sachi Vohra, TERI NOVEMBER 2018 COAL TRANSITION IN INDIA 1 © COPYRIGHT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Content from this discussion paper may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided it is attributed to the source. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to the address: The Energy and Resources Institute Darbari Seth Block, India Habitat Centre, Lodhi Road, New Delhi – 110 003, India Author Mr Thomas Spencer, Fellow, TERI, Mr Raghav Pachouri, Associate Fellow, TERI, Mr G. Renjith, Research Associate, TERI, and Ms Sachi Vohra, Project Associate, TERI Reviewers Mr R R Rashmi, Distinguished Fellow, TERI and Mr Karan Mangotra, Fellow & Associate Director, TERI ACKNOWLEDGMENT This paper has been produced as part of the efforts of Climate Transparency, an international partnership of TERI and 13 other research organizations and NGOs comparing G20 climate action – www.climate-transparency.org. The paper is financed by the International Climate Initiative (IKI). The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) supports this initiative on the basis of a decision adopted by the German Bundestag. The authors would like to thank the following people for their constructive comments on earlier drafts: Mr. RR Rashmi, Distinguished Fellow, TERI. Mr Karan Mangotra, Associate Director, TERI. Ms. Jesse Burton, Energy Research Centre, University of Cape Town. Ms. Lena Donat, Germanwatch. Ms. Hannah Schindler, Climate Transparency. Mr. Leo Roberts, Overseas Development Institute. All opinions expressed, as well as omissions and eventual errors are the responsibility of the authors alone. SUGGESTED FORMAT FOR CITATION Spencer, Thomas et al.