Coal in India Adjusting to Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AR-15-16 with Cover.Pmd

Annual Report 2015-16 (April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016) OF CHEM E IC T A U L T I E T N S G N I I N E N E A I R D S N I E STD. 1947 Indian Institute of Chemical Engineers 1 List of Council Members for 2015 & 2016 2015 Designation 2016 Mr G V Sethuraman, Director, Enfab Industries Pvt. Ltd., C-2, Shantiniwas, Mettuguda, Mr Shyam Bang, Executive Director, Jubilant Life Sciences Ltd., 1A, Sector 16A, Noida Secunderabad – 500 017, Andhra Pradesh, [O] (040) 2782-4343, 2782-0010/2782-3073, President - 201 301, Uttar Pradesh, [R] (011) 2922-9999, [Mobile] (0)9810106660, [R] (040) 2733-4321/5363, [Mobile] 9849028854, [email protected] [email protected] Prof Ch V Ramachandra Murthy, Department of Chemical Engineering, Andhra Univer- Immediate Past Mr G V Sethuraman, Enfab Industries Pvt. Ltd., Plot No. 138-A, IDA Mallapur, Hyderabad sity, Waltair, Visakhapatnam 530 003, [O] (0891) 2754871 Extn.496, [R] (0891) 2504520, President 500 076, Andhra Pradesh, O] (040) 2782-4343, 2782-0010/2782-3073, [R] (040) 2733- [Mobile] (0)94403 89136, [email protected] 4321/5363, [Mobile] 9849028854, [email protected] Mr D M Butala, 5, Mohak, B/h. Manisha Society, Behind Raja’s Lavkush, Bunglow, Near Prof S V Satyanarayana, Department of Chemical Engineering, JNTUA College of Upendra Bhatt’s Bunglow, Syed Vasana Road, Baroda 390 015, [R] (0265) 225-3977, Engineering, Anantapuramu Dist., Andhra Pradesh – 515002, [O] (08554) 272325 Ext: [Mobile] (0)9979853514, [email protected] Vice 4602, [Mobile] (0)9849509167, [email protected] Presidents Prof V V Basava Rao, Plot No; 184, Tirumala Nagar Colony, Meerpet (V), Moula-Ali Hous- Prof G A Shareef, 9, 2nd Stage, 2 Block, R M V Extn. -

India: Inventory of Estimated Budgetary Support and Tax Expenditures for Fossil-Fuels

INDIA: INVENTORY OF ESTIMATED BUDGETARY SUPPORT AND TAX EXPENDITURES FOR FOSSIL-FUELS Energy resources and market structure India is one of the fastest growing energy markets in the world. The country is the world’s third largest coal producer owing to its large deposits. Coal is the leading primary fuel in India’s energy mix, accounting for 44% of the country’s total primary energy supply (TPES), with thermal power plants making up the majority of coal consumption. Biomass accounts for 25% of total energy use, followed by oil and natural gas, which account respectively for 22% and 7% of the country’s energy needs. Remaining energy sources, such as nuclear power and hydro-electricity, account for about 1% each. The country’s proven reserves of oil were 5.5 billion barrels as of December 2012; nonetheless, domestic production falls far short of domestic demand and the country depends heavily on imported crude oil. The state-owned coal company, Coal India Limited (CIL), retains a near monopoly of coal extraction, with over 90% of domestic coal extraction attributed to government-controlled mines. Most coal mining occurs in the states of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and West Bengal. Market reforms are being implemented to bring competition and transparency to the coal sector. The government has been grappling to get an effective regulatory framework in place, which includes the loosening of regulations for the coal industry, with the objective of moving some grades of coal closer to international market prices, and allocating additional coal blocks through a transparent open bidding process. -

Reforming Soes in Asia: Lessons from Competition Law and Policy in India

ADBI Working Paper Series REFORMING SOES IN ASIA: LESSONS FROM COMPETITION LAW AND POLICY IN INDIA Vijay Kumar Singh No. 1056 December 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute Vijay Kumar Singh is a professor and head of the Department of Law and Management at the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies School of Law in Dehradun, India. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Singh, V. K. 2019. Reforming SOEs in Asia: Lessons from Competition Law and Policy in India. ADBI Working Paper 1056. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/reforming-soes-asia-lessons-competition-law-policy-india Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building, 8th Floor 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan Tel: +81-3-3593-5500 Fax: +81-3-3593-5571 URL: www.adbi.org E-mail: [email protected] © 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute ADBI Working Paper 1056 V. -

Chapter 15 Mining

CHAPTER 15 MINING 15.1. India is endowed with significant mineral resources. India produces about 100 minerals out of which 4 are Fuel minerals, 11 Metallic, 52 Non-metallic and the rest minor minerals. India is the world’s largest producer of mica blocks and mica splittings. With the recent spurt in world demand for chromate, India has stepped up its production to reach the second rank among the chromate producers of the world. Besides, India ranks, 3rd in production of Coal & Lignite, 2nd in Barites, 4th in Iron ore, 5th in Bauxite and crude Steel, 7th in Manganese ore and 8th in Aluminum. 15.2. The Ministry of Mines is responsible for the survey and exploration of all minerals (other than Natural Gas and Petroleum), for mining and metallurgy of Non-ferrous metals like Aluminum, Copper, Zinc, Lead, Gold, Nickel, etc., and for the administration of the Mines and Minerals, other than Coal, Natural Gas and Petroleum. The Ministry of Mines has jurisdiction over Geological Survey of India and Indian Bureau of Mines, both of which are subordinate offices. Geological Survey of India (GSI) 15.3. The GSI is the principal agency responsible for the assessment of geological and regional mineral resources of the country. GSI was established in 1851 and is one of India’s oldest investigative agencies in the field of earth sciences. Its areas of operation encompass scientific surveys and research and for locating mineral resources. GSI operates through six regional offices and four specialized wings – Marine, Coal Geophysics, Airborne surveys and Training. 15.4. The GSI has to its credit geological mapping, covering an area of approximately 3,146 million sq.km, or 94 percent of the area of India. -

“Power Finance Corporation - Investors Interaction Meet”

“Power Finance Corporation - Investors Interaction Meet” May 31, 2018 MANAGEMENT: TEAM OF POWER FINANCE CORPORATION:- - Mr. Rajeev Sharma - Chairman and Managing Director - Mr. D. Ravi - Director (Commercial) - Mr. C. Gangopadhyay - Director (Project) - Shri Sitaram Pareek - Independent Director Page 1 of 23 Power Finance Corporation May 31, 2018 Speaker: Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen. On behalf of Power Finance Corporation, we feel honored and privileged to welcome you all to this Investors Interaction Meet. The company recently announced its financial results for the year 2017-18 and has been successful in maintaining its growth trajectory. PFC is always aiming to connect with its investor and build a strong and enduring positive relationship with the investment community. With this objective, today’s event has been organized to discuss PFC’s current performance and future outlook with the current and prospective investors. On the desk in the center is Chairman and Managing Director -- Shri Rajeev Sharma along with the other directors. To my immediate left is Shri DRavi – Director, Commercial. Next to him is Shri C Gangopadhyay – Director, Projects. To my extreme left is Shri Sitaram Pareek – Independent Director and beside him is Shri N.B. Gupta – Director, Finance. They are all in front of you to give a brief insight of PFC’s performance during the financial year 2017-18. They will also present to you a roadmap for the forthcoming year. I request Shri Rajeev Sharma -- Chairman and Managing Director to address the gathering. Rajeev Sharma: Thank you very much for sparing your valuable time to be present here during this interaction. -

1 Pleistocene Climatic Changes in Western India

Abstract submitted for Mini Workshop “Future of the Past” to held at Gateway Hotel, Manglore, November 21 to 26, 2011 Pleistocene Climatic Changes in Western India: A Geoarchaeological Approach S.N. Rajaguru, Sushama G. Deo and Sheila Mishra Deccan College, Pune Recently Dhavalikar in his A. Ghosh memorial lecture titled “Indian Archaeology in the 21st Century” delivered on 25th September 2011, in New Delhi, strongly emphasized the need of understanding past cultural changes in terms of palaeoenvironment. He has suggested that growth and decay of protohistoric and historic cultures in India have been largely influenced by changes in the intensity of monsoonal rainfall during the Holocene, approximately last 10,000 years. In the last 25 years considerable new scientific data have been generated for the Holocene climatic changes in India (Singhvi and Kale 2009). It is observed that the early Holocene (~ 10 ka years to 4 ka years) was significantly wetter than the late Holocene (< 4 ka years). These changes in summer rainfall of India have been mainly due to global climatic factors. In the present communication we have attempted to understand prehistoric cultural changes against the background of climatic changes of the Pleistocene, approximately covering time span from about 2 Ma years BP to about 10 ka BP. Recently Sanyal and Sinha (2010) and Singhvi et al (2011-12) have attempted reconstruction of palaeomonsoon in Indian subcontinent by using data generated through multidisciplinary studies of marine cores, continental- fluvial, fluvio- lacustral, aeolian, glacial and littoral deposits- preserved in different parts of India. However, there is no input of prehistoric cultural changes in these publications. -

Morphotectonic of Sabarmati-Cambay Basin, Gujarat, Western India V.21, No.5, Pp: 371-383

J. Ind. Geophys. Union ( September 2017 ) Morphotectonic of Sabarmati-Cambay basin, Gujarat, Western India v.21, no.5, pp: 371-383 Morphotectonic of Sabarmati-Cambay basin, Gujarat, Western India Vasu Pancholi*1, Girish Ch Kothyari1, Siddharth Prizomwala1, Prabhin Sukumaran2, R. D. Shah3, N. Y. Bhatt3 Mukesh Chauhan1 and Raj Sunil Kandregula1 1Institute of Seismological Research, Raisan Gandhinagar, Gujarat 2Charotar University of Science and Technology (CHARUSAT), Vallabh Vidhyanagar, Gujarat 3Department of Geology, MG. Science College Ahmedabad, Gujarat *Corresponding Author: [email protected] ABSTracT The study area is a part of the peri-cratonic Sabarmati-Cambay rift basin of western Peninsular India, which has experienced in the historical past four earthquakes of about six magnitude located at Mt. Abu, Paliyad, Tarapur and Gogha. Earthquakes occurred not only along the two major rift boundary faults but also on the smaller longitudinal as well as transverse faults. Active tectonics is the major controlling factor of landform development, and it has been significantly affected by the fluvial system in the Sabarmati- Cambay basin. Using the valley morphology and longitudinal river profile of the Sabarmati River and adjoining trunk streams, the study area is divided into two broad tectono-morphic zones, namely Zone-1 and Zone-2. We computed stream length gradient index (SL) and steepness index (Ks) to validate these zones. The study suggests that the above mentioned structures exert significant influence on the evolution of fluvial landforms, thus suggesting tectonically active nature of the terrain. Based on integration of the morphometry and geomorphic expressions of tectonic instability, it is suggested that Zone-2 is tectonically more active as compared to Zone-1. -

Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India This Page Intentionally Left Blank Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India

Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India This page intentionally left blank Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India David Hall-Matthews © David Hall-Matthews 2005 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2005 978-1-4039-4902-8 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-52538-6 ISBN 978-0-230-51051-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230510517 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

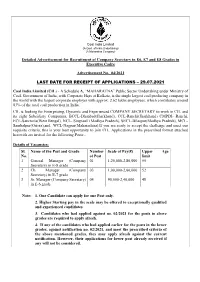

Detailed Advertisement for Recruitment of Company Secretary in E6, E7 and E8 Grades in Executive Cadre

Coal India Limited (A Govt. of India Undertaking) (A Maharatna Company) Detailed Advertisement for Recruitment of Company Secretary in E6, E7 and E8 Grades in Executive Cadre Advertisement No. 04/2021 LAST DATE FOR RECEIPT OF APPLICATIONS – 29.07.2021 Coal India Limited (CIL) - A Schedule A, “MAHARATNA” Public Sector Undertaking under Ministry of Coal, Government of India, with Corporate Hqrs at Kolkata, is the single largest coal producing company in the world with the largest corporate employer with approx. 2.62 lakhs employees, which contributes around 83% of the total coal production in India. CIL is looking for Enterprising, Dynamic and Experienced COMPANY SECRETARY to work in CIL and its eight Subsidiary Companies, BCCL-Dhanbad(Jharkhand), CCL-Ranchi(Jharkhand) CMPDI- Ranchi, ECL-Sanctoria(West Bengal), NCL- Singrauli (Madhya Pradesh), SECL-Bilaspur(Madhya Pradesh), MCL- Sambalpur(Orissa),and WCL-Nagpur(Maharashtra).If you are ready to accept the challenge and meet our requisite criteria, this is your best opportunity to join CIL. Applications in the prescribed format attached herewith are invited for the following Posts:- Details of Vacancies: Sl. Name of the Post and Grade Number Scale of Pay(₹) Upper Age No. of Post limit 1 General Manager (Company 01 1,20,000-2,80,000 55 Secretary) in E-8 grade 2 Ch. Manager (Company 03 1,00,000-2,60,000 52 Secretary) in E-7 grade 3 Sr. Manager (Company Secretary) 04 90,000-2,40,000 48 in E-6 grade Note- 1. One Candidate can apply for one Post only. 2. Higher Starting pay in the scale may be offered to exceptionally qualified and experienced candidates. -

Ngo Documents 2013-08-14 00:00:00 Coal India Investor Brief High Risk

High risk, low return COAL INDIA LTD’s shareholder value is threatened by poor corporate governance, faulty reserve estimations, regulatory risk and macro-economic issues. Introduction Coal India Limited is the world’s largest coal miner, with a production of 435 million metric tons (MT) in 2011 -201 2. There is significant pressure on CIL to deliver annual production growth rates in excess of 7%. The company has a 201 7 production target of 61 5 MT.[1 ] Coal India’s track record raises questions over its ability to deliver this rate of growth. In addition, serious governance issues are likely to impact CIL’s financial performance. These pose a financial and reputational risk to CIL, its shareholders and lenders, while macro- economic issues in the Indian energy economy pose a long term threat to Coal India. • CIL’s attempts to access new mining areas are facing widespread opposition from local communities and environmental groups. With its reliance on open-pit mining, access to new mines are essential for CIL to achieve production targets. G • CIL has grown reliant on shallow, open pit mining for 90% of its production, and has lost in-house expertise on deep mining techniques. N I • CIL has a record of poor corporate governance, manifested in rampant corruption, poor worker safety and repeated legal violations. This has, in the last year alone, led to penalties and F closure notices for over 50 mines, threatening both its financial performance and reputation. E I • CIL’s financial performance has been affected by directives from majority shareholder Government of India to keep coal prices artifically low.[2] According to one estimate, this cost R CIL $1 .75 billion in the 201 2-1 3 financial year alone.[3] The government has also taken away coal blocks allocated to CIL and given them to private players.[4] B • Changing economics of coal power in India; renewable energies are becoming cost- competitive even as coal faces increased regulatory scrutiny and public opposition. -

Countering Coal? a Discussion Paper by Kalpavriksh and Greenpeace

Countering Coal? A discussion paper by Kalpavriksh and Greenpeace Greenpeace is a global campaigning organisation that Kalpavriksh (KV) is a voluntary group based in India, acts to change attitudes and behaviour, to protect and working on environmental education, research, conserve the environment and to promote peace by: campaigns, and direct action. It began in 1979, with a students' campaign to save Delhi's Ridge Forest area Catalysing an energy revolution to address the number from encroachments and destruction. Starting with these one threat facing our planet: climate change. roots in local action, KV has moved on to work on a number of local, national, and global issues. Its activities Defending our oceans by challenging wasteful and are directed to ensuring conservation of biological destructive fishing, and creating a global network diversity, challenging the current destructive path of of marine reserves. 'development', helping in the search for alternative forms of livelihoods and development, assisting local Protecting the world’s remaining ancient forests and communities in empowering themselves to manage their the animals, plants and people that depend natural resources, and reviving a sense of oneness with on them. nature. Working for disarmament and peace by reducing KV has been helping communities and civil society dependence on finite resources and calling for the groups to implement the Forest Rights Act, specifically elimination of all nuclear weapons. its Community Forest Rights provisions, as a means of achieving more effective and equitable conservation Creating a toxic-free future with safer alternatives as also checking damage to forests by destructive to hazardous chemicals in today’s products and development projects. -

Mining in India

® By in-house counsel, for in-house counsel.® InfoPAKSM Energy and Natural Resources Multi-Jurisdictional Guide: Mining in India Sponsored by: Association of Corporate Counsel Association of Corporate Counsel 1025 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 200 1025 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 USA Washington, DC 20036 USA tel +1 202.293.4103, fax +1 202.293.4701 tel +1 202.293.4103, fax +1 202.293.4701 www.acc.com www.acc.com 2 Energy and Natural Resources Multi-Jurisdictional Guide: Mining in India Energy and Natural Resources Multi-Jurisdictional Guide: Mining in India December 2014 Provided by the Association of Corporate Counsel 1025 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 USA tel +1 202.293.4103 fax +1 202.293.4107 www.acc.com This InfoPAKSM provides a high level overview of the domestic mining sector, its regulatory structure and ownership, the environment and health and safety. It covers foreign ownership and tax issues and proposals for reform. The information in this InfoPAKSM should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representative of the views of PLC or of ACC SM or any of its lawyers, unless so stated. This InfoPAK is not intended as a definitive statement on the subject but rather to serve as a resource providing practical information for the reader. This material was developed by PLC. For more information about PLC, visit their website at http://www.practicallaw.com/ or see the “About the Author” section of this document. Copyright © 2014 Practical Law Company (PLC) & Association of Corporate Counsel 3 Contents I.