Conservation Strategy for the Pygmy Hippopotamus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts of Roads and Hunting on Central African Rainforest Mammals

Impacts of Roads and Hunting on Central African Rainforest Mammals WILLIAM F. LAURANCE,∗ BARBARA M. CROES,† LANDRY TCHIGNOUMBA,† SALLY A. LAHM,†‡ ALFONSO ALONSO,† MICHELLE E. LEE,† PATRICK CAMPBELL,† AND CLAUDE ONDZEANO† ∗Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 2072, Balboa, Republic of Panam´a, email [email protected] †Monitoring and Assessment of Biodiversity Program, National Zoological Park, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20560–0705, U.S.A. ‡Institut de Recherche en Ecologie Tropicale, B.P. 180, Makokou, Gabon Abstract: Road expansion and associated increases in hunting pressure are a rapidly growing threat to African tropical wildlife. In the rainforests of southern Gabon, we compared abundances of larger (>1kg) mammal species at varying distances from forest roads and between hunted and unhunted treatments (com- paring a 130-km2 oil concession that was almost entirely protected from hunting with nearby areas outside the concession that had moderate hunting pressure). At each of 12 study sites that were evenly divided between hunted and unhunted areas, we established standardized 1-km transects at five distances (50, 300, 600, 900, and 1200 m) from an unpaved road, and then repeatedly surveyed mammals during the 2004 dry and wet seasons. Hunting had the greatest impact on duikers (Cephalophus spp.), forest buffalo (Syncerus caffer nanus), and red river hogs (Potamochoerus porcus), which declined in abundance outside the oil concession, and lesser effects on lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) and carnivores. Roads depressed abundances of duikers, si- tatungas (Tragelaphus spekei gratus), and forest elephants (Loxondonta africana cyclotis), with avoidance of roads being stronger outside than inside the concession. -

PDF File Containing Table of Lengths and Thicknesses of Turtle Shells And

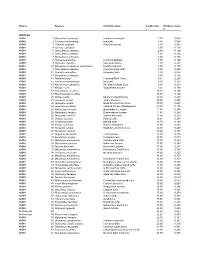

Source Species Common name length (cm) thickness (cm) L t TURTLES AMNH 1 Sternotherus odoratus common musk turtle 2.30 0.089 AMNH 2 Clemmys muhlenbergi bug turtle 3.80 0.069 AMNH 3 Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise 3.90 0.050 AMNH 4 Testudo carbonera 6.97 0.130 AMNH 5 Sternotherus oderatus 6.99 0.160 AMNH 6 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 7 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 8 Homopus areolatus Common padloper 7.95 0.100 AMNH 9 Homopus signatus Speckled tortoise 7.98 0.231 AMNH 10 Kinosternon subrabum steinochneri Florida mud turtle 8.90 0.178 AMNH 11 Sternotherus oderatus Common musk turtle 8.98 0.290 AMNH 12 Chelydra serpentina Snapping turtle 8.98 0.076 AMNH 13 Sternotherus oderatus 9.00 0.168 AMNH 14 Hardella thurgi Crowned River Turtle 9.04 0.263 AMNH 15 Clemmys muhlenbergii Bog turtle 9.09 0.231 AMNH 16 Kinosternon subrubrum The Eastern Mud Turtle 9.10 0.253 AMNH 17 Kinixys crosa hinged-back tortoise 9.34 0.160 AMNH 18 Peamobates oculifers 10.17 0.140 AMNH 19 Peammobates oculifera 10.27 0.140 AMNH 20 Kinixys spekii Speke's hinged tortoise 10.30 0.201 AMNH 21 Terrapene ornata ornate box turtle 10.30 0.406 AMNH 22 Terrapene ornata North American box turtle 10.76 0.257 AMNH 23 Geochelone radiata radiated tortoise (Madagascar) 10.80 0.155 AMNH 24 Malaclemys terrapin diamondback terrapin 11.40 0.295 AMNH 25 Malaclemys terrapin Diamondback terrapin 11.58 0.264 AMNH 26 Terrapene carolina eastern box turtle 11.80 0.259 AMNH 27 Chrysemys picta Painted turtle 12.21 0.267 AMNH 28 Chrysemys picta painted turtle 12.70 0.168 AMNH 29 -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian -

A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates

veterinary sciences Review A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates Hendrik Swanepoel 1,2, Jan Crafford 1 and Melvyn Quan 1,* 1 Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases Research Programme, Department of Veterinary Tropical Disease, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0110, South Africa; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-12-529-8142 Abstract: (1) Background: Viral diseases are important as they can cause significant clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals, as well as in humans. They also make up a large proportion of emerging infectious diseases. (2) Methods: A scoping review of peer-reviewed publications was performed and based on the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. (3) Results: The final set of publications consisted of 145 publications. Thirty-two viruses were identified in the publications and 50 African ungulates were reported/diagnosed with viral infections. Eighteen countries had viruses diagnosed in wild ungulates reported in the literature. (4) Conclusions: A comprehensive review identified several areas where little information was available and recommendations were made. It is recommended that governments and research institutions offer more funding to investigate and report viral diseases of greater clinical and zoonotic significance. A further recommendation is for appropriate One Health approaches to be adopted for investigating, controlling, managing and preventing diseases. Diseases which may threaten the conservation of certain wildlife species also require focused attention. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

The U.K. Hunter Who Has Shot More Wildlife Than the Killer of Cecil the Lion

CAMPAIGN TO BAN TROPHY HUNTING Special Report The U.K. hunter who has shot more wildlife than the killer of Cecil the Lion SUMMARY The Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting is revealing the identity of a British man who has killed wild animals in 5 continents, and is considered to be among the world’s ‘elite’ in the global trophy hunting industry. Malcolm W King has won a staggering 36 top awards with Safari Club International (SCI), and has at least 125 entries in SCI’s Records Book. The combined number of animals required for the awards won by King is 528. Among his awards are prizes for shooting African ‘Big Game’, wild cats, and bears. King has also shot wild sheep, goats, deer and oxen around the world. His exploits have taken him to Asia, Africa and the South Pacific, as well as across Europe. The Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting estimates that around 1.7 million animals have been killed by trophy hunters over the past decade, of which over 200,000 were endangered species. Lions are among those species that could be pushed to extinction by trophy hunting. An estimated 10,000 lions have been killed by ‘recreational’ hunters in the last decade. Latest estimates for the African lion population put numbers at around 20,000, with some saying they could be as low as 13,000. Industry groups like Safari Club International promote prizes which actively encourage hunters to kill huge numbers of endangered animals. The Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting believes that trophy hunting is an aberration in a civilised society. -

Using Non-Invasive Faecal Hormone Metabolite Monitoring to Detect

Research article Using non-invasive faecal hormone metabolite monitoring to detect reproductive patterns, seasonality and pregnancy in red river hogs (Potamochoerus porcus) Jocelyn Bryant1, Nadja Wielebnowski2, Diane Gierhahn1, Tina Houchens1, Astrid Bellem1, Amy Roberts1 and Joan Daniels1 1 Chicago Zoological Society, Brookfield Zoo, Brookfield, Illinois, USA 2Oregon Zoo, Portland, Oregon, USA Correspondence: Jocelyn Bryant, Department of Conservation Science, Chicago Zoological Society, Brookfield Zoo, 3300 Golf Rd, Brookfield, IL 60513, USA; Jocelyn. [email protected] JZAR Research article Research JZAR Keywords: Abstract androgen, faecal hormone metabolite, Few studies have been conducted on red river hog (Potamochoerus porcus) reproductive biology in oestrous cycle, progesterone, porcine, zoos. Furthermore, in spite of regular breeding efforts in zoos, reproductive success has been relatively seasonality poor for this species, particularly in the North American population. In this study, we used faecal hormone metabolite monitoring to analyse near daily samples from two males and three females Article history: over several years to gain insight into their patterns of reproductive hormone secretion. Both a Received: 4 February 2015 progesterone and a testosterone enzyme immunoassay (EIA) were validated and subsequently used to Accepted: 15 January 2016 monitor reproductive patterns, seasonality, ovulatory activity and a successful pregnancy. The findings Published online: 31 January 2016 indicate that female red river hogs are seasonally polyoestrous. Regular cycles were observed from approximately December through August and an annual period of anoestrous was observed from approximately September until December. Average cycle length for all females was 23 days ± 1.19, range 13–30 days. Androgen excretion patterns of the two males did not show clear seasonal patterns. -

CONSERVATION of the PYGMY HIPPOPOTAMUS (Choeropsis Liberiensis) in SIERRA

CONSERVATION OF THE PYGMY HIPPOPOTAMUS (Choeropsis liberiensis) IN SIERRA LEONE, WEST AFRICA by APRIL LEANNE CONWAY (Under the Direction of John P. Carroll and Sonia M. Hernandez) ABSTRACT The pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis, hereafter pygmy hippo) is an endangered species endemic to the Upper Guinea Rainforests of West Africa. Major threats to their continued survival include poaching for meat and deforestation. With increasing human populations and subsequent land use changes, pygmy hippo survival is far from certain. Understanding their ecology and behavior requires knowledge of the anthropogenic forces that influence them. I report on a study conducted on and around a protected area, Tiwai Island Wildlife Sanctuary, in southeastern Sierra Leone. The objective of this research was to explore local knowledge about pygmy hippos and human-wildlife interactions, test radio transmitter attachment methods, evaluate physical capture methods for radio transmitter attachment, and explore the use of camera trapping to determine occupancy and activity patterns of pygmy hippos. My results suggested that while the majority of local residents in the study area do not believe pygmy hippos have any benefits, environmental outreach may positively influence attitudes. Furthermore, the potential for using public citizens in scientific research facilitates exchange of knowledge. For radio telemetry transmitter attachment, I found that a hose-shaped collar was the best and caused minimal abrasion to the pygmy hippo. In the field, I attempted to physically capture pygmy hippos using pitfall traps, and successfully caught a male pygmy hippo in October 2010. However, more time is needed to capture multiple hippos. Camera trapping allowed for estimation of occupancy and activity patterns on Tiwai Island and the surrounding unprotected islands, and also recorded previously undocumented species in the area like the bongo Tragelaphus eurycerus. -

ANIMAL ADVENTURE GUIDES Information to Engage Your Students in Discussion and Discovery

This activity guide was created to lead you and your students on a learning expedition through Nashville Zoo. You may use this ANIMAL ADVENTURE GUIDES information to engage your students in discussion and discovery. Remember, your primary responsibility is to keep your group FEATURED TOPIC: ANIMAL ADAPTATIONS with you at all times. A map is provided on the backside to help guide the way to exhibits. Have fun! TOOL KIT FOR SURVIVAL Every animal has special traits or features that help them live in their specific environment. These features are called adaptations. Whether its talons or tusks, spots or spines, each animal is equipped with a tool kit for survival. ADAPTATIONS: PHYSICAL OR BEHAVIORAL? Adaptations can usually be grouped into 2 categories- physical or behavioral. Physical adaptations refer to something on the animal’s body (i.e. sharp claws, horns or keen eyesight). Behavioral adaptatins refer to something the animals does (i.e. migration, camouflage or hibernation). EAT OR BE EATEN Both predator and prey animals use adaptations that help them survive. Predators are animals that hunt other animals. For example, a cougar uses soft, padded feet to quietly sneak up on small animals. Prey are animals that are hunted by other animals. For example, a rabbit uses excellent eyesight and speed to escape its predators. TN STATE STANDARD ALIGNMENT: Interdependence (Grades K-2, 4-8) Flow of Matter and Energy (Grades K, 2-4) Biodiversity and Change (Grades 1-4, 5, 8) Photo credits: Amiee Stubbs Giraffe 1 THROUGHOUT THE ZOO Sheep BOTSWANA OVERLOOK (Private Rental Area) Cow To learn more about adaptations, follow the path on the map below to Barn Rhinoceros Owl GRASSMERE HISTORIC visit the highlighted animal exhibits. -

CENTRAL AFRICAN WILDLIFE ADVENTURES (CAWA) ALL PRICES ARE LISTED in EUROS Hunt Both Sides of the Famous Chinko River in Eastern C.A.R

BOOKED BY SHUNNESON & WILSON ADVENTURES Ken Wilson 803-792-4200 [email protected] www.shunnesonwilson.com CENTRAL AFRICAN WILDLIFE ADVENTURES (CAWA) ALL PRICES ARE LISTED IN EUROS Hunt both sides of the famous Chinko River in eastern C.A.R. (one of the world’s most remote wilderness hunts) 2016 (January – April) Precious Game Safari with 1 Precious (12 days) Species allowed: 1 precious game (Lord Derby Eland, Bongo, Leopard or Giant Forest Hog), 1 buffalo, 1 roan, 1 hartebeest or waterbuck, 1 warthog, 1 red river hog, 1 harnessed bushbuck, 1 yellow-back duiker, 1 red-flanked duiker, 1 western bush duiker, 1 blue duiker, 1 oribi, 1 vervet monkey, 1 patas monkey, 1 baboon, 1 hare, 1 cane rat, 1 turaco, 2 guinea fowls Hunting Dip & Air Safari Fee License Pack Charter TOTAL 1 hunter with 1 PH 15,500 2,000 3,500 4,500 25,500 Observer in Shared Lodging 3,200 2,750 5,950 Observer in Separate Lodging 4,500 2,750 7,250 Precious Game Safari with 2 Precious (19 days) Species allowed: 2 precious game (Lord Derby Eland, Bongo, Leopard or Giant Forest Hog), 1 buffalo, 1 roan, 1 hartebeest or waterbuck, 1 warthog, 1 red river hog, 1 harnessed bushbuck, 1 yellow-back duiker, 1 red-flanked duiker, 1 western bush duiker, 1 blue duiker, 1 oribi, 1 vervet monkey, 1 patas monkey, 1 baboon, 1 hare, 1 cane rat, 1 turaco, 2 guinea fowls Hunting Dip & Air Safari Fee License Pack Charter TOTAL 1 hunter with 1 PH 25,500 2,000 4,000 4,500 36,000 Observer in Shared Lodging 3,900 2,750 6,650 Observer in Separate Lodging 5,800 2,750 8,550 Precious Game Safari -

Cameroon Rainforest and Savannah 2018 13 Day Classic Safari- 1X1

WWW.SAFARITRACKERS.COM Cameroon Rainforest and Savannah 2018 13 Day Classic Safari- 1x1 basis in Savannah or Rainforest: €50,000 2 Major Species + 4 Small Species on Permit SAVANNAH ITINERARY RAINFOREST ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Douala, Overnight at Pullman Hotel Day 1: Arrival Douala, Overnight at Pullman Hotel Day 2: National flight to north and drive into Day 2: Extra day in Douala to ensure bags and guns hunting area arrived Day 3-15: 13 Full days of hunting Day 3: Charter to Libongo or Lokomo and drive Day 16: National flight back to Douala and into camp departure same evening. Day 4-16: 13 Full days of hunting Day 17: Charter to Douala and departure same evening 15 Day Collector Safari- 1x1 basis in Savannah or Rainforest: €70,000 4 Major Species (Elephant for Collector only) + 6 Small Species on Permit SAVANNAH ITINERARY RAINFOREST ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Douala, Overnight at Pullman Hotel Day 1: Arrival Douala, Overnight at Pullman Hotel Day 2: National flight to north and drive into Day 2: Extra day in Douala to ensure bags and guns hunting area arrived Day 3-17: 15 Full days of hunting Day 3: Charter to Libongo or Lokomo and drive Day 18: National flight back to Douala and into camp departure same evening. Day 4-18: 15 Full days of hunting Day 19: Charter to Douala and departure same evening Category Savannah Rainforest Eland Bongo Major West African Savanah Buffalo Dwarf Forest Buffalo Western Roan Forest Sitatunga Species Sing-sing Waterbuck Elephant (Collector Safari Only) Harnessed Bushbuck Western Hartebeest Giant Forest Hog Central African Kob Red River Hog Red River Hog Peter’s Duiker Small Nigerian Bohor Reedbuck Blue Duiker Species Red Flanked Duiker Bay Duiker Western Bush Duiker Bates Pygmy Antelope Oribi Warthog WWW.SAFARITRACKERS.COM NOTE ABOUT CHARTERS: At this time, there is no charter needed for Savannah Safaris, Forest only. -

Outstanding Male Hunter of the Year Award Criteria & Form

OUTSTANDING MALE HUNTER OF THE YEAR AWARD APPLICATION CANDIDATE NAME: EMAIL ADDRESS: PHONE NUMBER: YEAR OF ENTRY: NOMINATED BY: EMAIL ADDRESS: PHONE NUMBER: The purpose of this award is to recognize the Outstanding Male Hunter of the Year for Houston Safari Club Foundation. ENTRY CRITERIA 1. The applicant must have hunted at least 100 species across 4 continents. 2. Prospective recipients must submit their application by November 1st of the year prior to the Award being given. 3. The applicant must be 21 years of age. 4. The applicant must be a voting, active member of Houston Safari Club Foundation, in good standing. 5. The applicant must be of good character and have a known ethical hunting standard. 6. Applicants will be judged on the following categories: a. Hunting Accomplishments: Number of hunts, quality of species; difficulty of hunts b. Membership/History with Houston Safari Club Foundation: Length of time as member of HSCF; service to HSCF and our programs by attendance at annual convention; monthly meetings, club events. c. Wildlife Conservation/Education and Humanitarian Efforts 7. Please submit your entry by mail or email to: Joe Betar HSCF Executive Director Houston Safari Club Foundation 14811 St. Mary’s Lane Suite 265 Houston, TX 77079 [email protected] Houston Safari Club Foundation 14811 St. Mary's Lane, Suite 265 Houston, TX 77079 I. Please list any accomplishments of merit, special awards and related activities in the field of big game hunting that you have received. Houston Safari Club Foundation 14811 St. Mary's Lane, Suite 265 Houston, TX 77079 II.