Impacts of Roads and Hunting on Central African Rainforest Mammals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rural Highways

Rural Highways Updated July 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45250 Rural Highways Summary Of the nation’s 4.1 million miles of public access roads, 2.9 million, or 71%, are in rural areas. Rural roads account for about 30% of national vehicle miles traveled. However, with many rural areas experiencing population decline, states increasingly are struggling to maintain roads with diminishing traffic while at the same time meeting the needs of growing rural and metropolitan areas. Federal highway programs do not generally specify how much federal funding is used on roads in rural areas. This is determined by the states. Most federal highway money, however, may be used only for a designated network of highways. While Interstate Highways and other high-volume roads in rural areas are eligible for these funds, most smaller rural roads are not. It is these roads, often under the control of county or township governments, that are most likely to have poor pavement and deficient bridges. Rural roads received about 37% of federal highway funds during FY2009-FY2015, although they accounted for about 30% of annual vehicle miles traveled. As a result, federal-aid-eligible rural roads are in comparatively good condition: 49% of rural roads were determined to offer good ride quality in 2016, compared with 27% of urban roads. Although 1 in 10 rural bridges is structurally deficient, the number of deficient rural bridges has declined by 41% since 2000. When it comes to safety, on the other hand, rural roads lag; the fatal accident rate on rural roads is over twice the rate on urban roads. -

Road Impact on Deforestation and Jaguar Habitat Loss in The

ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 ABSTRACT ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 Copyright by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando 2008 Abstract The construction of roads, either as an economic tool or as necessity for the implementation of other infrastructure projects is increasing in the tropical forest worldwide. However, roads are one of the main deforestation drivers in the tropics. In this study we analyzed the impact of road investments on both deforestation and jaguar habitat loss, in the Mayan Forest. As well we used these results to forecast the impact of two road investments planned in the region. Our results show that roads are the single deforestation driver in low developed areas, whether many other drivers play and important role in high developed areas. In the short term, the impact of a road in a low developed area is lower than in a road in a high developed area, which could be the result of the lag effect between road construction and forest colonization. -

Impact of Highway Capacity and Induced Travel on Passenger Vehicle Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Impact of Highway Capacity and Induced Travel on Passenger Vehicle Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Policy Brief Susan Handy, University of California, Davis Marlon G. Boarnet, University of Southern California September 30, 2014 Policy Brief: http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/sb375/policies/hwycapacity/highway_capacity_brief.pdf Technical Background Document: http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/sb375/policies/hwycapacity/highway_capacity_bkgd.pdf 9/30/2014 Policy Brief on the Impact of Highway Capacity and Induced Travel on Passenger Vehicle Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Susan Handy, University of California, Davis Marlon G. Boarnet, University of Southern California Policy Description Because stop-and-go traffic reduces fuel efficiency and increases greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, strategies to reduce traffic congestion are sometimes proposed as effective ways to also reduce GHG emissions. Although transportation system management (TSM) strategies are one approach to alleviating traffic congestion,1 traffic congestion has traditionally been addressed through the expansion of roadway vehicle capacity, defined as the maximum possible number of vehicles passing a point on the roadway per hour. Capacity expansion can take the form of the construction of entirely new roadways, the addition of lanes to existing roadways, or the upgrade of existing highways to controlled-access freeways. One concern with this strategy is that the additional capacity may lead to additional vehicle travel. The basic economic principles of supply and demand explain this phenomenon: adding capacity decreases travel time, in effect lowering the “price” of driving; when prices go down, the quantity of driving goes up (Noland and Lem, 2002). An increase in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) attributable to increases in capacity is called “induced travel.” Any induced travel that occurs reduces the effectiveness of capacity expansion as a strategy for alleviating traffic congestion and offsets any reductions in GHG emissions that would result from reduced congestion. -

Reducing Carbon Emissions from Transport Projects

Evaluation Study Reference Number: EKB: REG 2010-16 Evaluation Knowledge Brief July 2010 Reducing Carbon Emissions from Transport Projects Independent Evaluation Department ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank APTA – American Public Transportation Association ASIF – activity–structure–intensity–fuel BMRC – Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation BRT – bus rapid transit CO2 – carbon dioxide COPERT – Computer Programme to Calculate Emissions from Road Transport DIESEL – Developing Integrated Emissions Strategies for Existing Land Transport DMC – developing member country EIRR – economic internal rate of return EKB – evaluation knowledge brief g – grams GEF – Global Environment Facility GHG – greenhouse gas HCV – heavy commercial vehicle IEA – International Energy Agency IED – Independent Evaluation Department IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change kg/l – kilogram per liter km – kilometer kph – kilometer per hour LCV – light commercial vehicle LRT – light rail transit m – meter MJ – megajoule MMUTIS – Metro Manila Urban Transportation Integration Study MRT – metro rail transit NAMA – nationally appropriate mitigation actions NH – national highway NHDP – National Highway Development Project NMT – nonmotorized transport NOx – nitrogen oxide NPV – net present value PCR – project completion report PCU – passenger car unit PRC – People’s Republic of China SES – special evaluation study TA – technical assistance TEEMP – transport emissions evaluation model for projects UNFCCC – United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change USA – United States of America V–C – volume to capacity VKT – vehicle kilometer of travel VOC – vehicle operating cost NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Key Words adb, asian development bank, greenhouse gas, carbon emissions, transport, emission saving, carbon footprint, adb transport sector operation, induced traffic, carbon dioxide emissions, vehicles, roads, mrt, metro transport Director General H. -

Road Sector Development and Economic Growth in Ethiopia1

ROAD SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AND ECONOMIC GROWTH IN ETHIOPIA1 Ibrahim Worku2 Abstract The study attempts to see the trends, stock of achievements, and impact of road network on economic growth in Ethiopia. To do so, descriptive and econometric analyses are utilized. From the descriptive analysis, the findings indicate that the stock of road network is by now growing at an encouraging pace. The government’s spending has reached tenfold relative to what it was a decade ago. It also reveals that donors are not following the footsteps of the government in financing road projects. The issue of rural accessibility still remains far from the desired target level that the country needs to have. Regarding community roads, both the management and accountancy is weak, even to analyze its impact. Thus, the country needs to do a lot to graduate to middle income country status in terms of road network expansion, community road management and administration, and improved accessibility. The econometric analysis is based on time series data extending from 1971‐2009. Augmented Cobb‐Douglas production function is used to investigate the impact of roads on economic growth. The model is estimated using a two‐step efficient GMM estimator. The findings reveal that the total road network has significant growth‐spurring impact. When the network is disaggregated, asphalt road also has a positive sectoral impact, but gravel roads fail to significantly affect both overall and sectoral GDP growth, including agricultural GDP. By way of recommendation, donors need to strengthen their support on road financing, the government needs to expand the road network with the aim of increasing the current rural accessibility, and more attention has to be given for community road management and accountancy. -

The Road to Clean Transportation

The Road to Clean Transportation A Bold, Broad Strategy to Cut Pollution and Reduce Carbon Emissions in the Midwest The Road to Clean Transportation A Bold, Broad Strategy to Cut Pollution and Reduce Carbon Emissions in the Midwest Alana Miller and Tony Dutzik, Frontier Group Ashwat Narayanan, 1000 Friends of Wisconsin Peter Skopec, WISPIRG Foundation August 2018 Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank Kevin Brubaker, Deputy Director, Environmental Law & Policy Center; Gail Francis, Strategic Director, RE-AMP Network; Sean Hammond, Deputy Policy Director, Michigan Environmental Council; Karen Kendrick-Hands, Co-founder, Transportation Riders United and Member of Citizens’ Climate Lobby; Brian Lutenegger, Program Associate, Smart Growth America; and Chris McCahill, Deputy Director, and Eric Sundquist, Director, State Smart Transportation Initiative for their review of drafts of this document, as well as their insights and suggestions. Thanks also to Gideon Weissman of Frontier Group for editorial support, and to Huda Alkaff of Wisconsin Green Muslims; Bill Davis and Cassie Steiner of Sierra Club – John Muir Chapter; Megan Owens of Transportation Riders United; and Abe Scarr of Illinois PIRG for their expertise throughout the project. The authors thank the RE-AMP Network for making this report possible. The authors also thank the RE-AMP Network for its work to articulate a decarbonization strategy that “includes everyone, electrifies everything and decarbonizes electricity,” concepts we drew upon for this report. The WISPIRG Foundation and 1000 Friends of Wisconsin thank the Sally Mead Hands Foundation for generously supporting their work for a 21st century transportation system in Wisconsin. The WISPIRG Foundation thanks the Brico Fund for generously supporting its work to transform transportation in Wisconsin. -

PDF File Containing Table of Lengths and Thicknesses of Turtle Shells And

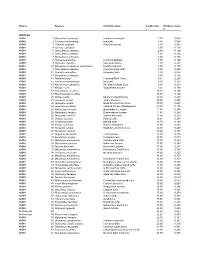

Source Species Common name length (cm) thickness (cm) L t TURTLES AMNH 1 Sternotherus odoratus common musk turtle 2.30 0.089 AMNH 2 Clemmys muhlenbergi bug turtle 3.80 0.069 AMNH 3 Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise 3.90 0.050 AMNH 4 Testudo carbonera 6.97 0.130 AMNH 5 Sternotherus oderatus 6.99 0.160 AMNH 6 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 7 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 8 Homopus areolatus Common padloper 7.95 0.100 AMNH 9 Homopus signatus Speckled tortoise 7.98 0.231 AMNH 10 Kinosternon subrabum steinochneri Florida mud turtle 8.90 0.178 AMNH 11 Sternotherus oderatus Common musk turtle 8.98 0.290 AMNH 12 Chelydra serpentina Snapping turtle 8.98 0.076 AMNH 13 Sternotherus oderatus 9.00 0.168 AMNH 14 Hardella thurgi Crowned River Turtle 9.04 0.263 AMNH 15 Clemmys muhlenbergii Bog turtle 9.09 0.231 AMNH 16 Kinosternon subrubrum The Eastern Mud Turtle 9.10 0.253 AMNH 17 Kinixys crosa hinged-back tortoise 9.34 0.160 AMNH 18 Peamobates oculifers 10.17 0.140 AMNH 19 Peammobates oculifera 10.27 0.140 AMNH 20 Kinixys spekii Speke's hinged tortoise 10.30 0.201 AMNH 21 Terrapene ornata ornate box turtle 10.30 0.406 AMNH 22 Terrapene ornata North American box turtle 10.76 0.257 AMNH 23 Geochelone radiata radiated tortoise (Madagascar) 10.80 0.155 AMNH 24 Malaclemys terrapin diamondback terrapin 11.40 0.295 AMNH 25 Malaclemys terrapin Diamondback terrapin 11.58 0.264 AMNH 26 Terrapene carolina eastern box turtle 11.80 0.259 AMNH 27 Chrysemys picta Painted turtle 12.21 0.267 AMNH 28 Chrysemys picta painted turtle 12.70 0.168 AMNH 29 -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian -

Natural Capital & Roads: Managing

Natural Capital & Roads Managing dependencies and impacts on ecosystem services for sustainable road investments Natural Capital & Roads | 1 Natural Capital & Roads: Managing dependencies and impacts on ecosystem services for sustainable road investments provides an introduction to incorporating ecosystem services into road design and development. It is intended to help transportation specialists and road engineers at the Inter-American Development Bank as well as others planning and building roads to identify, prioritize, and proactively manage the impacts the environment has on roads and the impacts roads have on the environment. This document provides practical examples of how natural capital thinking has been useful to road development in the past, and how ecosystem services can be incorporated into future road projects. Natural Capital & Roads was written by Lisa Mandle and Rob Griffin of the Natural Capital Project and Josh Goldstein of The Nature Conservancy for the Inter-American Development Bank. The document was designed and edited by Elizabeth Rauer and Victoria Peterson of the Natural Capital Project. Its production was supervised by Rafael Acevedo-Daunas, Ashley Camhi, and Michele Lemay at the Inter-American Development Bank. The Natural Capital Project is an innovative partnership with the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment, The Nature Conservancy, and the World Wildlife Fund, aimed at aligning economic forces with conservation. The Nature Conservancy is the leading conservation organization working around the world to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and people. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) is the main source of multilateral financing in Latin America. -

A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates

veterinary sciences Review A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates Hendrik Swanepoel 1,2, Jan Crafford 1 and Melvyn Quan 1,* 1 Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases Research Programme, Department of Veterinary Tropical Disease, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0110, South Africa; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-12-529-8142 Abstract: (1) Background: Viral diseases are important as they can cause significant clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals, as well as in humans. They also make up a large proportion of emerging infectious diseases. (2) Methods: A scoping review of peer-reviewed publications was performed and based on the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. (3) Results: The final set of publications consisted of 145 publications. Thirty-two viruses were identified in the publications and 50 African ungulates were reported/diagnosed with viral infections. Eighteen countries had viruses diagnosed in wild ungulates reported in the literature. (4) Conclusions: A comprehensive review identified several areas where little information was available and recommendations were made. It is recommended that governments and research institutions offer more funding to investigate and report viral diseases of greater clinical and zoonotic significance. A further recommendation is for appropriate One Health approaches to be adopted for investigating, controlling, managing and preventing diseases. Diseases which may threaten the conservation of certain wildlife species also require focused attention. -

471. Ghazoul Road Expansion

Edinburgh Research Explorer Road expansion and persistence in forests of the Congo Basin Citation for published version: Kleinschroth, F, Laporte, N, Laurance, WF, Goetz, SJ & Ghazoul, J 2019, 'Road expansion and persistence in forests of the Congo Basin', Nature Sustainability, vol. 2, no. 7, pp. 628-634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0310-6 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1038/s41893-019-0310-6 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Nature Sustainability General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 1 Road expansion and persistence in forests of the Congo Basin 2 Fritz Kleinschroth*1, Nadine Laporte2, William F. Laurance3, Scott Goetz4, Jaboury Ghazoul1,5,6 3 1Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zurich, Universitätsstr. 16, 8092 Zurich, 4 Switzerland 5 2School of Forestry, Northern Arizona University, -

7091-Roads and Landslides in Nepal: How Development Affects Environmental Risk

McAdoo et al., Roads and Landslides in Nepal Page 1 of 11 7091-Roads and landslides in Nepal: How development affects environmental risk McAdoo , B.G. (1)., Quak, M. (1), Gnyawali, K. R. (2), Adhikari, B. R. (3), Devkota, S. (3), Rajbhandari, P. (4), Sudmeier-Rieux, K. (5) 1. Yale-NUS College, Singapore 2. Natural Hazards Section, Himalayan Risk Research Institute (HRI), Nepal 3. Department of Civil Engineering, Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, Nepal 4. Independent, Kathmandu, Nepal 5. University of Lausanne, Faculty of Geosciences and Environment, Institute of Earth Science, Switzerland Abstract. The number of deaths from landslides in Nepal has been increasing dramatically due to a complex combination of earthquakes, climate change, and an explosion of road construction that will only be increasing as China’s Belt and Road Initiative seeks to construct three major trunk roads through the Nepali Himalaya. To determine the effect of informal roads on generating landslides, we measure the spatial distribution of roads and landslides triggered by the 2015 Gorkha earthquake and those triggered by monsoon rainfalls prior to 2015, as well as a set of randomly located landslides. As landslides generated by earthquakes are generally related to the geology, geomorphology and earthquake parameters, their distribution should be distinct from the rainfall-triggered slides that are more impacted by land use. We find that monsoon-generated landslides are almost twice as likely to occur within 100 m of a road than the landslides generated by the earthquake and the distribution of random slides in the same area. Based on these findings, geoscientists, planners and policymakers must consider how roads are altering the landscape, and how development affects the physical (and ecological), socio-political and economic factors that increases risk in exposed communities.