IDENTITY, PHYSICALITY, and the TWILIGHT of COLORADO's VICE DISTRICTS Submitted By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludacris Word of Mouf Full Album

Ludacris, Word Of Mouf Full Album Zip 1 / 4 Ludacris, Word Of Mouf Full Album Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Word Of Mouf | Ludacris to stream in hi-fi, or to download in True CD Quality on Qobuz.com.. Play full-length songs from Word Of Mouf by Ludacris on your phone, computer and home audio system with Napster.. Ludacris - Word Of Mouf - Amazon.com Music. ... Listen to Word Of Mouf [Explicit] by Ludacris and 50 million songs with Amazon Music Unlimited. $9.99/month .... Download Word Of Mouf (Explicit) by Ludacris at Juno Download. Listen to this and ... Block Lockdown (album version (Explicit) feat Infamous 2-0). 07:48. 96.. 2001 - Ludacris - ''Wоrd Of Mouf''. Tracklist. 01. "Coming 2 America". 02. ... Tracklist. 01 - Intro. 02 - Georgia. 03 - Put Ya Hands Up. 04 - Word On The Street (Skit).. Word of Mouf is the third studio album by American rapper Ludacris; it was released on November 27, 2001, by Disturbing tha Peace and Def Jam South.. Word of Mouf by Ludacris songs free download.. Facebook; Twitter .. Explore the page to download mp3 songs or full album zip for free.. ludacris word of mouf zip ludacris word of mouf songs ludacris word of mouf download ludacris word of mouf full album . View credits, reviews, tracks and shop for the 2001 CD release of Word Of Mouf on Discogs. ... Word Of Mouf (CD, Album) album cover ... Tracklist Hide Credits .... Ludacris - Back for the First Time (Full album). Enoch; 16 ... Play & Download Ludacris - Word Of Mouf itunes zip Only On GangstaRapTalk the.. Download Word of Mouf 2001 Album by Ludacris in mp3 CBR online alongwith Karaoke. -

Copyright by Eric Alan Ratliff 2003

Copyright by Eric Alan Ratliff 2003 The Dissertation Committee for Eric Alan Ratliff Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Price of Passion: Performances of Consumption and Desire in the Philippine Go-Go Bar Committee: ____________________________________ Douglas Foley, Supervisor ____________________________________ Kamran Asdar Ali ____________________________________ Robert Fernea ____________________________________ Ward Keeler ____________________________________ Mark Nichter The Price of Passion: Performances of Consumption and Desire in the Philippine Go-Go Bar by Eric Alan Ratliff, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 Acknowledgements A project of this scope and duration does not progress very far without the assistance of many people. I would first like to acknowledge my dissertation committee members for their advice and encouragement over these many years. Douglas Foley, Ward Keeler, Robert Fernea, Kamran Ali and Mark Nichter provided constructive comments during those times when I could not find the right words and continuing motivation when my own patience and enthusiasm was waning. As with the subjects of my study, their ‘stories’ of ethnographic practice were both informative and entertaining at just the right moments. Many others have also offered inspiration and valuable suggestions over the years, including Eufracio Abaya, Laura Agustín, Priscilla Alexander, Dr. Nicolas Bautista, Katherine Frank, Jeanne Francis Illo, Geoff Manthey, Sachiyo Yamato, Aida Santos, Melbourne Tapper, and Kamala Visweswaran. This research would never have gotten off the ground without the support of the ReachOut AIDS Education Foundation (now ReachOut Foundation International). -

Thesis Finding Privacy in the Red-Light District

THESIS FINDING PRIVACY IN THE RED-LIGHT DISTRICT: AN ANALYSIS OF VICTORIAN ERA MEDICINE BOTTLES FROM THE VANOLI SITE (5OR.30) IN OURAY, COLORADO Submitted by Heather Horobik Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2011 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Mary Van Buren Ann Magennis Narda Robinson Copyright by Heather Horobik 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT FINDING PRIVACY IN THE RED-LIGHT DISTRICT: AN ANALYSIS OF VICTORIAN ERA MEDICINE BOTTLES FROM THE VANOLI SITE (5OR.30) IN OURAY, COLORADO A sample of bottles from the Vanoli Site (5OR.30), part of a Victorian era red- light district in Ouray, Colorado are examined. Previous archaeological studies involving the pattern analysis of brothel and red-light district assemblages have revealed high frequencies of medicine bottles. The purpose of this project was to determine whether a sense of privacy regarding health existed and how it could influence disposal patterns. The quantity and type of medicine bottles excavated from two pairs of middens and privies were compared. A concept of privacy was discovered to have significantly affected the location and frequency of medicine bottle disposal. A greater percentage of medicine bottles was deposited in privies, the private locations, rather than the more visually open and accessible middens. This study concludes that, while higher percentages of medicine bottles are found within brothel and red-light district locations, other factors such as privacy and feature type may affect the artifact patterns associated with such sites. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people helped and supported me throughout the process involved in completing this thesis. -

Ludacris the Red Light District Full Album Zip

Ludacris, The Red Light District Full Album Zip ERROR_GETTING_IMAGES-1 Ludacris, The Red Light District Full Album Zip 1 / 2 Hood Starz.com].rar hosted on mediafire.com 80.48 MB, Ludacris Chicken N Beer ... Ludacris, The Red Light District Full ;Enoch; 17 videos; 147,667 views חנוך .(Album Zip Download.. Ludacris - The Red Light District (Full album + Bonus Track Last updated on Jun 26, 2015. Subscribe! Play all. Share.. Find Ludacris discography, albums and singles on AllMusic. ... The Red Light District. 2004. The Red Light District · Def Jam South · Disturbing tha Peace. 2005.. Tracklist: 1. Intro, 2. Number One Spot, 3. Get Back, 4. Put Your Money, 5. Blueberry Yum Yum, 6. Child Of The Night, 7. The Potion, 8. Pass Out, 9. Skit, 10.. 2000 - Ludacris - ''Back For The First Time''. Tracklist. 01. "U Got a Problem?" 02. .... 2004 - Ludacris - ''The Red Light District''. Tracklist. 01. "Intro" Timbaland. 02.. Ludacris – The Red Light District. The Red Light District (CD, Album) album cover. More Images · All Versions · Edit Release · Sell This ... Tracklist Hide Credits .... The red light district. ludacris 320 kbps . Ludacris release therapy itunes . tags ludacris the red light district. Ludacris, the red light district full album zip .... Ludacris - The Red Light District review: Inconsistent, but primarily ... Release Date: 2004 | Tracklist .... I haven't heard a full one after this. Calc. Ludacris – Chicken-N-Beer – Album Zip Quality: iTunes Plus AAC M4A ... songs lyrics, songs mp3 download, download zip and complete full album rar. ... DVD made by of Ludacris visiting the red-light district, a growroom, .... 4 Download zip, rar. -

Anti-Racism Topic Paper

CEDA Topic Paper Anti-Racism Proposal 2016-17 Policy Debate Claudette Colvin C.T. Vivian Chase Iron Eyes T. R. M. Howard Yuri Kochiyama Reies López Tijerina Daisy Lee Gatson Bates Anti-Racism Topic Paper April 2016 Janet Escobedo, Georgia State University; Samuel Hanks, Georgia State University; Nadia Hussein, Georgia State University; and Dr. Kevin Kuswa, Berkeley Preparatory in Tampa, Florida. —with advice and feedback from Rashad Evans, University of Puget Sound and Dr. Tim Barouch, Georgia State University Page 1 of 161 “Paradigms, however, are like frost crystals that disappear on exposure to the sun. As soon as one starts talking about a paradigm, its days are numbered,” R. Delgado, ’12 “We’re living in more chains today -- through lockdowns, ankle bracelets, halfway houses,… -- than we were in the early 1800’s. That’s something to think about.” Frank W. Wilderson, ‘14 CEDA Topic Paper Anti-Racism Proposal 2016-17 Policy Debate Table of Contents Anti-Racism Topic Area Proposal .................................................................................................................................................... 4 I. “Anti-Racial Exclusion” Phrasing ........................................................................................................................ 9 Racial Disparity ............................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Racial Inequality ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Copyright by Jeffrey Wayne Parker 2013

Copyright by Jeffrey Wayne Parker 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Jeffrey Wayne Parker Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Empire’s Angst: The Politics of Race, Migration, and Sex Work in Panama, 1903-1945 Committee: Frank A. Guridy, Supervisor Philippa Levine Minkah Makalani John Mckiernan-González Ann Twinam Empire’s Angst: The Politics of Race, Migration, and Sex Work in Panama, 1903-1945 by Jeffrey Wayne Parker, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2013 Dedication To Naoko, my love. Acknowledgements I have benefitted greatly from a wide ensemble of people who have made this dissertation possible. First, I am deeply grateful to my adviser, Frank Guridy, who over many years of graduate school consistently provided unwavering support, needed guidance, and inspiration. In addition to serving as a model historian and mentor, he also read countless drafts, provided thoughtful insights, and pushed me on key questions and concepts. I also owe a major debt of gratitude to another incredibly gifted mentor, Ann Twinam, for her stalwart support, careful editing, and advice throughout almost every stage of this project. Her diligent commitment to young scholars immeasurably improved my own writing abilities and professional development as a scholar. John Mckiernan-González was also an enthusiastic advocate of this project who always provided new insights into how to make it better. Philippa Levine and Minkah Makalani also carefully read the dissertation, provided constructive insights, edited chapters, and encouraged me to develop key aspects of the project. -

Come Into My Parlor. a Biography of the Aristocratic Everleigh Sisters of Chicago

COME INTO MY PARLOR Charles Washburn LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN IN MEMORY OF STEWART S. HOWE JOURNALISM CLASS OF 1928 STEWART S. HOWE FOUNDATION 176.5 W27c cop. 2 J.H.5. 4l/, oj> COME INTO MY PARLOR ^j* A BIOGRAPHY OF THE ARISTOCRATIC EVERLEIGH SISTERS OF CHICAGO By Charles Washburn Knickerbocker Publishing Co New York Copyright, 1934 NATIONAL LIBRARY PRESS PRINTED IN U.S.A. BY HUDSON OFFSET CO., INC.—N.Y.C. \a)21c~ contents Chapter Page Preface vii 1. The Upward Path . _ 11 II. The First Night 21 III. Papillons de la Nun 31 IV. Bath-House John and a First Ward Ball.... 43 V. The Sideshow 55 VI. The Big Top .... r 65 VII. The Prince and the Pauper 77 VIII. Murder in The Rue Dearborn 83 IX. Growing Pains 103 X. Those Nineties in Chicago 117 XL Big Jim Colosimo 133 XII. Tinsel and Glitter 145 XIII. Calumet 412 159 XIV. The "Perfessor" 167 XV. Night Press Rakes 173 XVI. From Bawd to Worse 181 XVII. The Forces Mobilize 187 XVIII. Handwriting on the Wall 193 XIX. The Last Night 201 XX. Wayman and the Final Raids 213 XXI. Exit Madams 241 Index 253 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful appreciation to Lillian Roza, for checking dates John Kelley, for early Chicago history Ned Alvord, for data on brothels in general Tom Bourke Pauline Carson Palmer Wright Jack Lait The Chicago Public Library The New York Public Library and The Sisters Themselves TO JOHN CHAPMAN of The York Daily News WHO NEVER WAS IN ONE — PREFACE THE EVERLEIGH SISTERS, should the name lack a familiar ring, were definitely the most spectacular madams of the most spectacular bagnio which millionaires of the early- twentieth century supped and sported. -

Prostitutes, Feminists, and the War on White Slavery

Decades of Reform: Prostitutes, Feminists, and the War on White Slavery By: Jodie Masotta Under the direction of: Professor Nicole Phelps & Professor Major Jackson University of Vermont Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of Arts and Sciences, Honors College Department of History & Department of English April 2013 Introduction to Project: This research should be approached as an interdisciplinary project that combines the fields of history and English. The essay portion should be read first and be seen as a way to situate the poems in a historical setting. It is not merely an extensive introduction, however, and the argument that it makes is relevant to the poetry that comes afterward. In the historical introduction, I focus on the importance of allowing the prostitutes that lived in this time to have their own voice and represent themselves honestly, instead of losing sight of their desires and preferences in the political arguments that were made at the time. The poetry thus focuses on providing a creative and representational voice for these women. Historical poetry straddles the disciplines of history and English and “through the supremacy of figurative language and sonic echoes, the [historical] poem… remains fiercely loyal to the past while offering a kind of social function in which poetry becomes a ritualistic act of remembrance and imagining that goes beyond mere narration of history.”1 The creative portion of the project is a series of dramatic monologues, written through the voices of prostitutes that I have come to appreciate and understand as being different and individualized through my historical research The characters in these poems should be viewed as real life examples of women who willingly became prostitutes. -

Weeklies with Local Cartoons Are 'Truly Blessed'

Weeklies with local cartoons are ‘truly blessed’ By Marcia Martinek . Pages 1-3 Funding of journalism remains the Holy Grail By Anthony Longden . Pages 4-6 Fighting spirit: Competing hyperlocal sites outmatch regional newspaper’s community coverage By Barbara Selvin . Page 7-11 Extension journalism: Teaching students the real world and bringing a new type of journalism to a small town By Al Cross . Pages 12-18 Shared views: Social capital, community ties and Instagram By Leslie-Jean Thornton . Page 19-26 The EMT of multimedia: How to revive your newspaper’s future By Teri Finneman . Pages 27-32 volume 54, no. 3-4 • fall/winter 2013 grassroots editor • fall-winter 2013 Weeklies with local Editor: Dr. Chad Stebbins Graphic Designer: Liz Ford Grassroots Editor cartoons are ‘truly blessed’ (USPS 227-040, ISSN 0017-3541) is published quarterly for $25 per year by By Marcia Martinek the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors, Institute of International Studies, Missouri Southern When an 8-year-old girl saw an illustration in the Altamont (New York) Enterprise depict- State University, 3950 East Newman Road, ing her church, which was being closed by the Albany Diocese, she became upset. Forest Byrd, Joplin, MO 64801-1595. Periodicals post- then the illustrator for the newspaper, had drawn the church with a tilting steeple, being age paid at Joplin, Mo., and at strangled with vines as a symbol of what was happening in the diocese. additional mailing offices. The girl wrote to the newspaper, and Editor Melissa Hale-Spencer responded to her, explaining the role of cartoons in a newspaper along with affirming the girl’s action in writing POSTMASTER: Send address changes the letter. -

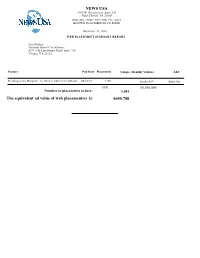

NEWS USA the Equivalent Ad Value of Web Placement(S)

NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 WEB PLACEMENT SUMMARY REPORT Lisa Fullam National Blood Clot Alliance 8321 Old Courthouse Road, Suite 255 Vienna, VA 22182 Feature Pub Date Placements Unique Monthly Visitors AEV Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood 08/10/16 1,001 50,058,999 $600,708 1001 50,058,999 Number of placements to date: 1,001 The equivalent ad value of web placement(s) is: $600,708 NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 National Blood Clot Alliance--Fullam WEB PLACEMENTS REPORT Feature: Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood Clot. Publication Date: 8/10/16 Unique Monthly Web Site City, State Date Vistors AEV 760 KFMB San Diego, CA 08/11/16 4,360 $52.32 96.5 Wazy ::: Today's Best Music, Lafayette Indiana Lafayette, IN 08/12/16 280 $3.36 Aberdeen American News Aberdeen, SD 08/11/16 14,800 $177.60 Abilene-rc.com Abilene, KS 08/11/16 0 $0.00 About Pokemon Go Cirebon, ID 09/08/16 0 $0.00 Advocate Tribune Online Granite Falls, MN 08/11/16 37,855 $454.26 aimmediatexas.com/ McAllen, TX 08/11/16 920 $11.04 Alerus Retirement Solutions Arden Hills, MN 08/12/16 28,400 $340.80 Alestle Live Edwardsville, IL 08/11/16 1,640 $19.68 Algona Upper Des Moines Algona, IA 08/11/16 680 $8.16 Amery Free Press. -

2016-Annual-Report.Pdf

2016ANNUAL REPORT PORTFOLIO OVE RVIEW NEW MEDIA REACH OF OUR DAILY OPERATE IN O VER 535 MARKETS N EWSPAPERS HAVE ACR OSS 36 STATES BEEN PUBLISHED FOR 100% MORE THAN 50 YEARS 630+ TOTAL COMMUNITY PUBLICATIONS REACH OVER 20 MILLION PEOPLE ON A WEEKLY BASIS 130 D AILY N EWSPAPERS 535+ 1,400+ RELATED IN-MARKET SERVE OVER WEBSITES SALES 220K REPRESENTATIVES SMALL & MEDIUM BUSINESSES SAAS, DIGITAL MARKETING SERVICES, & IT SERVICES CUMULATIVE COMMON DIVIDENDS SINCE SPIN-OFF* $3.52 $3.17 $2.82 $2.49 $2.16 $1.83 $1.50 $1.17 $0.84 $0.54 $0.27 Q2 2014 Q3 2014 Q4 2014 Q1 2015 Q2 2015 Q3 2015 Q4 2015 Q1 2016 Q2 2016 Q3 2016 Q4 2016 *As of December 25, 2016 DEAR FELLOW SHAREHOLDERS: New Media Investment Group Inc. (“New Media”, “we”, or the “Company”) continued to execute on its business plan in 2016. As a reminder, our strategy includes growing organic revenue and cash flow, driving inorganic growth through strategic and accretive acquisitions, and returning a substantial portion of cash to shareholders in the form of a dividend. Over the past three years since becoming a public company, we have consistently delivered on this strategy, and we have created a total return to shareholders of over 50% as of year-end 2016. Our Company remains the largest owner of daily newspapers in the United States with 125 daily newspapers, the majority of which have been published for more than 100 years. Our local media brands remain the cornerstones of their communities providing hyper-local news that our consumers and businesses cannot get anywhere else. -

ADD PRINT, ADD POWER Ops – PRESS RELEASE SERVICE

PRINT POWER ADD PRINT, ADD POWER oPS – PRESS RELEASE SERVICE ABOUT OUR PRESS RELEASE PRESS RELEASE SERVICE ZONE OPTIONS OPS’s Press Release Service delivers your news to You can choose to send your press release to any the right people, at the right price. Our service is the combination of these zones: (Add a photo to your fastest and most convenient way to get your informa- press release for $50) tion and photos to Oklahoma newspapers. HOW OUR PRESS RELEASE SERVICE WORKS You can choose from the entire state or specific regions. Simply send your press release electronically as a text file. Photos should be sent in TIF or JPG format (at least 200 dpi). $ STATEWIDE 325 158 Newspapers Our E-Press Release service will do the rest. The same day we receive your news release, or on the $ date you specify, we’ll have it in the hands of the CENTRAL 100 44 Newspapers (includes OKC area) newspapers you choose. $ TRACK YOUR NORTHWEST 50 22 Newspapers $ PRESS RELEASE NORTHEAST 100 38 Newspapers For an extra $100, we will track the results of your (includes Tulsa area) press release for four weeks. $ SOUTHWEST 50 22 Newspapers $ SOUTHEAST 50 28 Newspapers (405) 499-0020 1-888-815-2672 (in Okla.) OKLAHOMA PRESS SERVICE www.OkPress.com 3601 N. Lincoln Blvd., Oklahoma City, OK 73105 • www.OkPress.com PRINT POWER ADD PRINT, ADD POWER oPS – PRESS RELEASE SERVICE NEWspapers BY ZONES Seminole The Seminole Producer CENTRAL NORTHEAST NORTHWEST Spiro Spiro Graphic Ardmore Ardmoreite Afton The American Alva Alva Review-Courier Stigler Stigler News-Sentinel Blanchard