Report on Development of Drought Prone Areas National Committee On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kalahandi Forest Division Reserved Forests Name of Range Name Of

Kalahandi Forest Division Reserved Forests Name of range Name of Blocks Area in Hectares Govt. notification Madanpur –Rampur Tapranga 6839 Urladani 10737 Benaguda 5087 Sunamukhi 2399 Dengen 496 Jerka 1006 Turchi 246 Sadel”A” 282 Sadel “B” 320 Satami 1873 Telen 2630 Lumersingha 119 Bhatel 37 Sripali 46 Biswanathpur Champadeipur 67 Jhimri 1419 Raul 655 Bori 1448 Patraguda 179 Dhepaguda 464 Sargiguda 767 Kidding 688 Samjhola 893 Niyamgiri 2007 Porgel 1762 Dulma 565 Nachiniguda 1154 Jalkrida 1775 Machul 967 Benbhata 1657 Pahadpadar 1670 Kesinga Nangalguda 1474 Kamel 176 Karladanger 375 Madakhola’A’ 659 Kerbandi 1108 Bazargarh 7911 Kadalighati 1655 Narla 1293 Bhawanipatna Dhangada-Dhangidi 250 Kanamanjure 1932 Sinang 1178 Kutrukhai 315 Bhalu 60 Pordhar 704 Jugsaipatna 2084 Nehela 3956 Karlapat 7077 Alma 1404 Madakhol ‘B’ 645 Brahmani 5768 Dhanupanchan 740 Junagarh Ghana 3094 Kelia 232 Jalabandha ‘A’ 40 Jalabandha ‘B’ 28 Jalabandha ‘C’ 76 Pariagarh 810 Panigaon 508 Kandul 95 Barjan 355 Jharbandha 317 Sahajkhol 12521 Raktaboden 180 Talc hirka 140 Bhalujore 48 Balagaon 64 Dulkibandha 47 Ninaguda 71 Singhari 5887 Udayagiri 1197 Jerka 2754 Kegaon Daka 343 Kumkot 5000 Chura ‘A’ 7732 Chura ‘B’ 2333 Gujia 339 Lini 139 Ghatual 275 Adabori 921 Bisbhurni 212 Nageswar 3154 Thuamul-Rampur Thakuranipadar 83 Goyalkhoj 234 Kuspari 131 Khakes 74 Ampadar 94 Sulbadi 11 Baghmari 26 Arkhapedi 66 Kucharighati 33 Uperchikra 69 Ranipadar 62 Benakhamar 450 Kadokhaman 78 Bijaghati 38 Proposed reserved forest Name of the Range Name of the blocks Area in Hectors Notification with date I .Bhawanipatna Sagada 1069 Khandual 450.73 46268/R dt.02.06.75 Jugsaipatna Extn. -

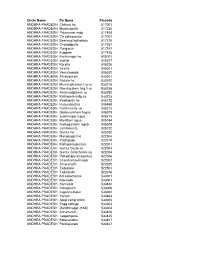

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Comparing Performance of Various Crops in Rajasthan State Based on Market Price, Economic Prices and Natural Resource Valuation

Economic Affairs, Vol. 63, No. 3, pp. 709-716, September 2018 DOI: 10.30954/0424-2513.3.2018.16 ©2018 New Delhi Publishers. All rights reserved Comparing Performance of Various Crops in Rajasthan state based on Market Price, Economic Prices and Natural Resource Valuation 1 1 1 2 1 3 M.K. Jangid , Latika Sharma , S.S. Burark , H.K. Jain , G.L. Meena and S.L. Mundra 1Department of Agricultural Economics and Management, Rajasthan College of Agriculture, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India 2Department of Agricultural Statistics and Computer Application, Rajasthan College of Agriculture, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India 3Department of Agronomy, Rajasthan College of Agriculture, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The study has assessed the performance of different crops and cropping pattern in the state of Rajasthan using alternative price scenarios like market prices; economic prices (net out effect of subsidy) and natural resource valuation (NRV) considering environmental benefits like biological nitrogen fixation and greenhouse gas costs. The study has used unit-level cost of cultivation data for the triennium ending 2013-14 which were collected from Cost of Cultivation Scheme, MPUAT, Udaipur (Raj.) for the present study. It has analyzed crop-wise use of fertilizers, groundwater, surface water and subsidies. The secondary data of cropping pattern was also used from 1991-95 to 2011-14 from various published sources of Government of Rajasthan. The study that even after netting out the input subsidies and effect on environment and natural resources, the cotton-vegetables cropping pattern was found more stable and efficient because of the higher net return of` 102463 per hectare with the next best alternate cropping patterns like clusterbean-chillies (` 86934/ha), cotton-wheat (` 69712/ha), clusterbean-wheat (` 64987/ ha) etc. -

Crop–Livestock Interactions and Livelihoods in the Gangetic Plains of Uttar Pradesh, India

cover.pdf 9/1/2008 1:53:50 PM ILRI International Livestock Research Institute Research Report 11 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Crop–livestock interactions and livelihoods in the Gangetic Plains of Uttar Pradesh, India R System IA w G id C slp e L i v e s t e oc m ISBN 92–9146–220–9 k Program Crop–livestock interactions and livelihoods in the Gangetic Plains of Uttar Pradesh, India Singh J, Erenstein O, Thorpe W and Varma A Corresponding author: [email protected] ILRI International Livestock Research Institute INTERNATIONAL LIVESTOCK RESEARCH P.O. Box 5689, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia INSTITUTE International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center P.O. Box 1041 Village Market-00621, Nairobi, Kenya Rice–Wheat Consoritum New Delhi, India R System IA w G id C slp e CGIAR Systemwide Livestock Programme L i v e s t e P.O. Box 5689, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia oc m k Program Authors’ affiliations Joginder Singh, Consultant/Professor, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India Olaf Erenstein, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), India William Thorpe, International Livestock Research Institute, India Arun Varma, Consultant/retired ADG ICAR, New Delhi, India © 2007 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute). All rights reserved. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided that such reproduction shall be subject to acknowledgement of ILRI as holder of copyright. Editing, design and layout—ILRI Publications Unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. ISBN 92–9146–220–9 Correct citation: Singh J, Erenstein O, Thorpe W and Varma A. 2007. Crop–livestock interactions and livelihoods in the Gangetic Plains of Uttar Pradesh, India. -

Neo Geographia an International Journal of Geography, GIS & Remote Sensing (ISSN-2319-5118)

Neo Geographia An International Journal of Geography, GIS & Remote Sensing (ISSN-2319-5118) Volume II Issue I January 2013 Coordinating Editors: Vikas Nagare & Anand Londhe Guest Editor: Dr. A. H. Nanaware Advisory Board: Dr. R. R. Patil Dr. N. G. Shinde Principal & Head, Department of Geography, Head, Department of Geography, K. N. Bhise Arts & Commerce college, Kurduwadi, D.B.F.Dayanand college of Arts & Science, Tal-madha, Dist-Solapur, Maharashtra Solapur, Maharashtra Dr. A. H. Nanaware Dr. S. C. Adavitot Associate Professor, Department of Geographyrch Head, Department of Geography, And Research centre C.B. Khedagis college, Akkalkot, Dist-Solapur, Shri Shivaji Mahavidyalaya, Maharashtra Barshi, Dist-Solapur, Maharashtra . Dr. (Miss.) Veena U. Joshi Professor, Department of Geography Pune University, Pune Maharashtra Neo Geographia is a refereed journal. Published by: Barloni Books, for Interactions Forum, Pune. Printed By: Barloni Books, MIT Road, Pune-411038 Official Address: Anand Hanumant Londhe, Interactions Forum, I/C of Sambhaji Shivaji Gat, 19, Bhosale Garden, MIT Road, Near Hotel Pooja, Kothrud, Pune, Maharashtra-411038 Email: [email protected]: www.interactionsforum.com Welcome to Interactions Forum!! Pune based Interactions Forum (IF) is established formally in the year 2010 with the objective to provide an integrated platform for intra-disciplinary and interdisciplinary research in various disciplines and to provide free access to the knowledge produced through this research. Today’s formal organization was preceded by an informal group of young research scholars who were very enthusiastic, besides their own fields of research, about the new and ongoing research in various branches of the knowledge tree. At present we are focusing on providing the researchers a space to publish their research. -

Impact Study of Rehabilitation & Reconstruction Process on Post Super Cyclone, Orissa

Draft Report Evaluation study of Rehabilitation & Reconstruction Process in Post Super Cyclone, Orissa To Planning Commission SER Division Government of India New Delhi By GRAMIN VIKAS SEWA SANSTHA 24 Paragana (North) West Bengal CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE NO. CHAPTER : I Study Objectives and Study Methodology 01 – 08 CHAPTER : II Super Cyclone: Profile of Damage 09 – 18 CHAPTER : III Post Cyclone Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Process 19 – 27 CHAPTER : IV Community Perception of Loss, Reconstruction and Rehabilitation 28 – 88 CHAPTER : V Disaster Preparedness :From Community to the State 89 – 98 CHAPTER : VI Summary Findings and Recommendations 99 – 113 Table No. Name of table Page no. Table No. : 2.1 Summary list of damage caused by the super cyclone 15 Table No. : 2.2 District-wise Details of Damage 16 STATEMENT SHOWING DAMAGED KHARIFF CROP AREA IN SUPER Table No. : 2.3 17 CYCLONE HIT DISTRICTS Repair/Restoration of LIPs damaged due to super cyclone and flood vis-à- Table No. : 2.4 18 vis amount required for different purpose Table No. : 3.1 Cyclone mitigation measures 21 Table No. : 4.1 Distribution of Villages by Settlement Pattern 28 Table No. : 4.2 Distribution of Villages by Drainage 29 Table No. : 4.3 Distribution of Villages by Rainfall 30 Table No. : 4.4 Distribution of Villages by Population Size 31 Table No. : 4.5 Distribution of Villages by Caste Group 32 Table No. : 4.6 Distribution of Population by Current Activity Status 33 Table No. : 4.7 Distribution of Population by Education Status 34 Table No. : 4.8 Distribution of Villages by BPL/APL Status of Households 35 Table No. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

(Rainy Season) and Summer Pearl Millet in Western India About ICRISAT

IMOD Inclusive Market Oriented Development Innovate Grow Prosper Working Paper Series no. 36 RP – Markets, Institutions and Policies Prospects for kharif (Rainy Season) and Summer Pearl Millet in Western India About ICRISAT The International Crops Research Institute Contact Information for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) is a ICRISAT-Patancheru ICRISAT-Bamako ICRISAT-Nairobi non-profit, non-political organization (Headquarters) (Regional hub WCA) (Regional hub ESA) that conducts agricultural research for Patancheru 502 324 BP 320 PO Box 39063, Nairobi, development in Asia and sub-Saharan Andhra Pradesh, India Bamako, Mali Kenya Africa with a wide array of partners Tel +91 40 30713071 Tel +223 20 223375 Tel +254 20 7224550 throughout the world. Covering 6.5 million Fax +91 40 30713074 Fax +223 20 228683 Fax +254 20 7224001 square kilometers of land in 55 countries, [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] the semi-arid tropics have over 2 billion ICRISAT-Liaison Office ICRISAT-Bulawayo ICRISAT-Maputo people, of whom 644 million are the CG Centers Block Matopos Research Station c/o IIAM, Av. das FPLM No 2698 A Amarender Reddy, P Parthasarathy Rao, OP Yadav, IP Singh, poorest of the poor. ICRISAT innovations NASC Complex PO Box 776 Caixa Postal 1906 help the dryland poor move from poverty Dev Prakash Shastri Marg Bulawayo, Zimbabwe Maputo, Mozambique NJ Ardeshna, KK Kundu, SK Gupta, Rajan Sharma, to prosperity by harnessing markets New Delhi 110 012, India Tel +263 383 311 to 15 Tel +258 21 461657 while managing risks – a strategy called Tel +91 11 32472306 to 08 Fax +263 383 307 Fax +258 21 461581 Inclusive Market- Oriented development Fax +91 11 25841294 [email protected] [email protected] Sawargaonkar G, Dharm Pal Malik, D Moses Shyam (IMOD). -

District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi District, Odisha

District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi, Odisha DISTRICT IRRIGATION PLAN OF KALAHANDI DISTRICT, ODISHA i District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi, Odisha Prepared by: District Level Implementation Committee (DLIC), Kalahandi, Odisha Technical Support by: ICAR-Indian Institute of Soil and Water Conservation (IISWC), Research Centre, Sunabeda, Post Box-12, Koraput, Odisha Phone: 06853-220125; Fax: 06853-220124 E-mail: [email protected] For more information please contact: Collector & District Magistrate Bhawanipatna :766001 District : Kalahandi Phone : 06670-230201 Fax : 06670-230303 Email : [email protected] ii District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi, Odisha FOREWORD Kalahandi district is the seventh largest district in the state and has spread about 7920 sq. kms area. The district is comes under the KBK region which is considered as the underdeveloped region of India. The SC/ST population of the district is around 46.31% of the total district population. More than 90% of the inhabitants are rural based and depends on agriculture for their livelihood. But the literacy rate of the Kalahandi districts is about 59.62% which is quite higher than the neighboring districts. The district receives good amount of rainfall which ranges from 1111 to 2712 mm. The Net Sown Area (NSA) of the districts is 31.72% to the total geographical area(TGA) of the district and area under irrigation is 66.21 % of the NSA. Though the larger area of the district is under irrigation, un-equal development of irrigation facility led to inequality between the blocks interns overall development. The district has good forest cover of about 49.22% of the TGA of the district. -

6. World Patterns of Agricultural Production Major Crops

DSE4T: Agricultural Geography Unit II 6. World Patterns of Agricultural Production Major Crops With varied types of relief, soils, climate and with plenty of sun-shine and long and short growing season, world has capability to grow each and every crop. Crops required tropical, sub-tropical and temperate climate can easily be grown in one or the other part of world. Crops are devided into following categories. 1. Food Crops: Rice, Wheat, Maize, Millets- Jowar, Bajra, Ragi; Gram, Tur (Arhar). 2. Cash Crops: Cotton, Jute, Sugarcane, Mustard, Tobacco, Groundnut, Sesamum, oilseeds Castorseed, Linseed etc 3. Plantation Crops: Tea, Coffee, Spices- Cardamom, Chillies, Ginger, Turmeric; Coconut and Rubber. 4. Horticulture: Fruits- Apple, Peach, Pear, Apricot, Almond, Strawberry, Mango, Banana, Vegetables. World production of major Food Crops (rice, wheat, maize, barley, rye, sorghum and millet) Rice Production Rice is the most important food crop. There are about 10,000 varieties if rice in the world. Rice is life for thousand of millions people obtain 60 to 70 percent of their calories from rice and their products. Recognising the importance of this crop, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2004 as the International Year of Rice. The theme of IYR –“Rice is Life” reflects the importance of rice as a primary food source. The Asian continent dominates in terms of global rice production, with China and India leading the way. Rice is among the three leading food crops of the world, with maize (corn) and wheat being the other two. All three directly provide no less than 42% of the world’s required caloric intake and, in 2009, human consumption was responsible for 78% of the total usage of produced rice. -

Report Name:Timely Arrival of Southwest Monsoon Promising For

Voluntary Report – Voluntary - Public Distribution Date: June 04,2020 Report Number: IN2020-0058 Report Name: Timely Arrival of Southwest Monsoon Promising for Kharif Crop Country: India Post: Mumbai Report Category: Agriculture in the News, Agricultural Situation, Climate Change/Global Warming/Food Security, Cotton and Products, Grain and Feed, Oilseeds and Products, Market Development Reports, Agriculture in the Economy Prepared By: Dhruv Sood Approved By: Lazaro Sandoval Report Highlights: On June 1, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) announced that the Southwest Monsoon had set over Kerala coinciding with its historically normal date. IMD also published its second long-range forecast predicting a normal Southwest Monsoon (June to September) for 2020. The rainfall is likely to be 102 percent of the long period average (LPA). The impact of super cyclone Amphan on crops in Eastern India is under assessment by government agencies, as Western India prepares for Cyclone Nisarga. THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY General Information Southwest Monsoon Onset On June 1, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) announced that the Southwest Monsoon had set over the coast of the southern state of Kerala coinciding with its normal date. The IMD had earlier forecast the arrival of monsoon rains over Kerala on June 5, four days later than usual. The timely arrival of monsoon bodes well for the Kharif 2020 crop that has faced delays due to labor shortages. The timely rains should provide adequate moisture, and accelerate the pace of planting across India as states gradually ease lockdown restrictions. -

Self-Employment

SELF-EMPLOYMENT A Framework for Implementation National Rural Livelihood Mission Ministry of Rural Development Government of India SELF-EMPLOYMENT A Framework for Implementation National Rural Livelihood Mission Ministry of Rural Development Government of India June 22, 2016 Executive Summary MoRD has been thinking about a strategy to systematically bring panchayats out of poverty within a clear timeline. Given that 51% of the rural workforce is self-employed, there is a need to create a policy framework for holistically improving self-employment opportunities for the rural poor. In the light of the above, a framework document titled Self-Employment–A Framework for Implementation (No.J-11060/1/2016-RL) dated June 22nd, 2016 has been prepared after a consultation with state representatives in NIRD&PR in Hyderabad on January 9, 2016 and a national consultation in Delhi at Vigyan Bhawan on January 14, 2016. Before the document is taken up for formal consideration at the GoI level, it was thought necessary to seek the opinion of State governments. Accordingly, a copy of the framework document is hereby attached for your comments. The framework proposes a new scheme within the NRLM framework called the Grameen Swarozghar Yojana (GSY) that would be implemented through inter-departmental collaboration. The proposal is to ensure that self-employment, skill up-gradation, and efficient delivery of government schemes and entitlements lead to poverty-free panchayats within a definite timeline. The new scheme is proposed on 7 key principles: 1. Build on the strengths of previous efforts while avoiding it weaknesses 2. Build on the recent success of establishing high quality SHGs through the CRP strategy 3.