Self-Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scholarship Scheme

Scholarship Scheme (Trust Fund) result for 3rd Qtr of Academic Year 2014-15 Scholarship amount has been credited to the bank account of concerned Students Course in Registration NAME AS PER Institute Name,institute Type Of Disability which Student Bank Student Bank Sr no. Sex Residential Address Student Bank Student A/c No Total Mobile No/mis BANK ACCOUNT address Disability Percentage Studying Branch RTGS/IFSC Code (current) Aliah University,Dn-18,sector- Vill-patna,po- v,salt Lake,kolkata,North 24 nityananda Pur,ps- STATE BANK OF BALGONA +91~727882 1 TF/14/00011 SK Hasibul M OH 55% B.TECH 31824264865 SBIN0012386 31000 Parganas,West Bengal - bhatar,Bardhaman,Wes INDIA BRANCH 4155 700091 t Bengal -713520 S/o Narasimman M, The Kavry College Of Sigaralahalli (vill) Educational,The Kavry College Moongilmaduvu (po), Of Educational M. Kalipatty, SYNDICATE +91~809898 2 TF/14/00068 Ramesh N M Pennagaram (tk) OH 60% M.ED ERIYUR 61732210020969 SYNB0006173 40000 Mecher (po) Salem BANK 3177 Dharmapuri (dt),Salem,Tamil Nadu - (dt),Dharmapur,Tamil 636453 Nadu -636810 Jrh University Chitrakoot Vill Betari Post STATE BANK OF SITAPUR +91~854594 3 TF/14/00279 Savitri Kumari F Up,Chitrakoot,Chitrakoot,Up - Bhabhuwa,Kaimu,Bihar - OH 75% B.ED. 33315991625 SBIN0003869 61000 INDIA CHITRAKOOT 6471 210204 821101 Eravukarithara House Government Engineering Kokkothamangalam P.o SOUTH INDIAN +91~773663 4 TF/14/00280 Shyam Ashok M College Thrissur, Kerala, OH 40% B.TECH CHERTHALA 0120053000035076 SIBL0000120 35430 Cherthala, Alappuzha BANK LTD 3620 India,Thrissur,Kerala -680009 688527 J R H University Village Sheshpur Post Chitrakoot,Jagadguru Surapur Teh Shahganj ALLAHABAD TAWAKKALPUR +91~873809 5 TF/14/00291 Rama Shankar M Rambhadracharya Dist Jaunpur Pin 228161 OH 80% B. -

Kalahandi Forest Division Reserved Forests Name of Range Name Of

Kalahandi Forest Division Reserved Forests Name of range Name of Blocks Area in Hectares Govt. notification Madanpur –Rampur Tapranga 6839 Urladani 10737 Benaguda 5087 Sunamukhi 2399 Dengen 496 Jerka 1006 Turchi 246 Sadel”A” 282 Sadel “B” 320 Satami 1873 Telen 2630 Lumersingha 119 Bhatel 37 Sripali 46 Biswanathpur Champadeipur 67 Jhimri 1419 Raul 655 Bori 1448 Patraguda 179 Dhepaguda 464 Sargiguda 767 Kidding 688 Samjhola 893 Niyamgiri 2007 Porgel 1762 Dulma 565 Nachiniguda 1154 Jalkrida 1775 Machul 967 Benbhata 1657 Pahadpadar 1670 Kesinga Nangalguda 1474 Kamel 176 Karladanger 375 Madakhola’A’ 659 Kerbandi 1108 Bazargarh 7911 Kadalighati 1655 Narla 1293 Bhawanipatna Dhangada-Dhangidi 250 Kanamanjure 1932 Sinang 1178 Kutrukhai 315 Bhalu 60 Pordhar 704 Jugsaipatna 2084 Nehela 3956 Karlapat 7077 Alma 1404 Madakhol ‘B’ 645 Brahmani 5768 Dhanupanchan 740 Junagarh Ghana 3094 Kelia 232 Jalabandha ‘A’ 40 Jalabandha ‘B’ 28 Jalabandha ‘C’ 76 Pariagarh 810 Panigaon 508 Kandul 95 Barjan 355 Jharbandha 317 Sahajkhol 12521 Raktaboden 180 Talc hirka 140 Bhalujore 48 Balagaon 64 Dulkibandha 47 Ninaguda 71 Singhari 5887 Udayagiri 1197 Jerka 2754 Kegaon Daka 343 Kumkot 5000 Chura ‘A’ 7732 Chura ‘B’ 2333 Gujia 339 Lini 139 Ghatual 275 Adabori 921 Bisbhurni 212 Nageswar 3154 Thuamul-Rampur Thakuranipadar 83 Goyalkhoj 234 Kuspari 131 Khakes 74 Ampadar 94 Sulbadi 11 Baghmari 26 Arkhapedi 66 Kucharighati 33 Uperchikra 69 Ranipadar 62 Benakhamar 450 Kadokhaman 78 Bijaghati 38 Proposed reserved forest Name of the Range Name of the blocks Area in Hectors Notification with date I .Bhawanipatna Sagada 1069 Khandual 450.73 46268/R dt.02.06.75 Jugsaipatna Extn. -

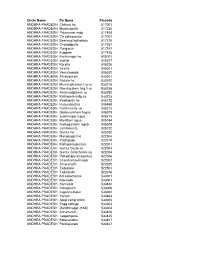

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asa

Branch Br.Name Code Address Contact No. 1 Dumka Marwarichowk ,Po- dumka,Dist - Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asanbani,Dist-Dumka, Pin-816123 VIA 7033293514 3 MAHESHPUR At+Po-Maheshpur Raj, Dist-Pakur,Pin-816106 7070896401 4 JAMA At+Po-Jama,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814162 7033293527 5 SHIKARIPARA At+Po-Shikaripara,Dist-Dumka,Pin 816118 7033293540 6 HARIPUR At+Po-Haripur,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814118 7033293526 7 PAKURIA At+Po-Pakuria,Dist-Pakur,Pin816117 7070896402 8 RAMGARH At+Po-Ramgarh,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814102 7033293536 9 HIRANPUR At+Po-Hiranpur,Dist-Pakur,Pin-816104 7070896403 10 KOTALPOKHAR PO-KOTALPOKHR, VIA- SBJ,DIST-SBJ,PIN- 816105 7070896382 11 RAJABHITA At+Po-Hansdiha] Dist-Godda] Pin-814101 7033293556 12 SAROUNI At+Po-Sarouni] Dist-Godda] Pin-814156 7033293557 13 HANSDIHA At+Po-Hansdiha,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293525 14 GHORMARA At+Po-Ghormara, Dist-Deoghar, Pin - 814120 7033293834 15 UDHWA At+Po-udhwa,Dist-Sahibganj pin-816108 7070896383 16 KHAGA At-Khaga,Po-sarsa,via-palajorihat,Pin-814146 7033293837 17 GANDHIGRAM At+Po-Gandhigram] Dist-Godda] Pin-814133 7033293558 18 PATHROLE At+po-pathrol,dist-deoghar,pin-815353 7033293830 19 FATHEPUR At+po-fatehpur,dist-Jamtara,pin-814166 7033293491 20 BALBADDA At+Po-Balbadda]Dist-Godda] Pin-813206 7033293559 21 BHAGAIYAMARI PO-SAKRIGALIGHAT,VIA-SBJ,PIN-816115 7070896384 22 MAHADEOGANJ PO-MAHADEVGANJ,VIA-SBJ,816109 7070896385 23 BANJHIBAZAR PO-SBJ AT JIRWABARI,816109 7070896386 24 DALAHI At-Dalahi,Po-Kendghata,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293519 25 PANCHKATHIA PO-PANCHKATIA,VIA BERHATE,816102 -

Jh G Ha Go Ar Odd Kh Da Ha a and D

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF SAND GOGODDADA JHHAARKHAHAND Content Table Sl. Content Page No. No. 1. Introduction 2-3 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 3 3. The List of Mining Leases in the District with 4-9 location, area and period of validity 4. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in last three 9 years 5. Detail of Production of Sand or Bajari or minor 9 mineral in last three years 6. Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of 9-10 the District 7. General Profile of the District 10 8. Land Utilization Pattern in the district: Forest, 10 Agriculture, Horticulture, Mining etc. 9. Physiography of the District 11-12 10. Rainfall: month-wise 13 11. Geology and Mineral Wealth 13-16 12. General Recommendations 17-18 12. Annexure- I 19-22 13. Annexure- II 23-24 14. Annexure- III 25 INTRODUCTION: As per the guidelines issued in Para 7 (iii) of Part-II- Section-3-Sub Section (ii) of Extraordinary Gazette of MoEF&CC, Government of India, New Delhi dated 15.01.2016 and in concurrence to directives issued by the Chief Secretary to Government, Government of Jharkhand vide letter no. 1874/C.S. dated 01/08/17 a District Survey Report (DSR) is to be prepared for each district in Jharkhand. The main spirit of preparing this report is to encourage Sustainable Mining and development. In this direction a team comprising of Mines and Geology, Irrigation, or Remote Sensing departments were given the task for preparing this report. An extensive field work was carried on 28/08/2017 and 29/08/2017 by the members of the committee to assess the possibilities of sand mining in the Godda district. -

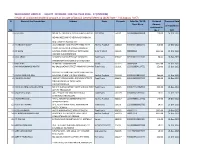

(INTERIM) Details of Unclaimed Dividend Amount As On

WOCKHARDT LIMITED - EQUITY DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2016 - 17 (INTERIM) Details of unclaimed dividend amount as on date of Annual General Meeting (AGM Date - 2nd August, 2017) SI Name of the Shareholder Address State Pin code Folio No / DP ID Dividend Proposed Date Client ID no. Amount of Transfer to unclaimed in No. (Rs.) IEPF 1 A G SUJAY NO 49 1ST MAIN 4TH CROSS HEALTH LAYOUT Karnataka 560091 1203600000360918 120.00 16-Dec-2023 VISHWANEEDAM PO NEAR NAGARABHAVI BDA COMPLEX BANGALORE 2 A HANUMA REDDY 302 HARBOUR HEIGHTS OPP PANCHAYAT Andhra Pradesh 524344 IN30048418660271 510.00 16-Dec-2023 OFFICE MUTHUKUR ANDHRA PRADESH 3 A K GARG C/O M/S ANAND SWAROOP FATEHGANJ Uttar Pradesh 203001 W0000966 3000.00 16-Dec-2023 [MANDI] BULUNDSHAHAR 4 A KALARANI 37 A(NEW NO 50) EZHAVAR SANNATHI Tamil Nadu 629002 IN30108022510940 50.00 16-Dec-2023 STREET KOTTAR NAGERCOIL,TAMILNADU 5 A M LAZAR ALAMIPALLY KANHANGAD Kerala 671315 W0029284 6000.00 16-Dec-2023 6 A M NARASIMMABHARATHI NO 140/3 BAZAAR STREET AMMIYARKUPPAM Tamil Nadu 631301 1203320004114751 250.00 16-Dec-2023 PALLIPET-TK THIRUVALLUR DT THIRUVALLUR 7 A MALLIKARJUNA RAO DOOR NO 1/1814 Y M PALLI KADAPA Andhra Pradesh 516004 IN30232410966260 500.00 16-Dec-2023 8 A NABESA MUNAF 46B/10 THIRUMANJANA GOPURAM STREET Tamil Nadu 606601 IN30108022007302 600.00 16-Dec-2023 TIRUVANNAMALAI TAMILNADU TIRUVANNAMALAI 9 A RAJA SHANMUGASUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST Tamil Nadu 614625 IN30177414782892 250.00 16-Dec-2023 AND TK THANJAVUR 10 A RAJESH KUMAR 445-2 PHASE 3 NETHAJI BOSE ROAD Tamil Nadu 632009 -

Page 1 of 29 GN-29, SECTOR-V, SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF HEALTH SERVICES NURSING SECTION SWASTHYA BHAWAN, 1ST FLOOR, WING-A GN-29, SECTOR-V, SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA – 700091 No. HNG/3A-1-2018/Part-1/750 Date: 09/08/2019 ORDER The following candidates, recommended by West Bengal Health Recruitment Board are hereby appointed temporarily as Staff Nurse, Grade-II under West Bengal Nursing Services Cadre in the Pay Band Scale of Rs. 7,100-37,600/- (minimum pay Rs. 7680/-) of Pay Band-3 with Grade Pay of Rs. 3,600/- related to WBS (ROPA) Rules, 2009 plus other allowances as admissible under existing Rules and posted at the Health Institutions as shown against their respective names in Column. No. 6 until further order. This appointment order has been issued on the basis of existing vacancies. This order will take immediate effect. SN Name Father's Name & Address Sex Caste Place Of Posting 1 2 3 4 5 6 G.YESUPRAKASAM, 5-17 KANCHIRAN Mal Super Speciality CATHERIN VILAI NEAR PALLIYADI RAILWAY 1 F UR Hospital, Jalpaiguri DAYA MARY.Y STATION, KANYAKUMARI, TAMILNADU, (SNCU) 629169 ANANDA BIHARI KHUNTIA, Vill- Sarapul Rural SUSHREE TARATUA, P.O- ISWARPUR, P.S- NILGIRI, Hospital, 2 SWAYANPRAVA F UR DISTERICT- BALESWAR, ODISHA, PIN- Basirhat Health KHUNTIA 756042 District MUHINDRO SINGH THOKCHOM, A46, ROMILA SSB SARANI, BIDHANAGAR, DURGAPUR Santipur State General 3 CHANU F UR 713212, BURDWAN, WEST BENGAL, Hospital, Nadia THOKCHOM 713212 MD GHIYASUDDIN, 11/1 H/10, MM ALI Sarapul Rural YASMIN 4 ROAD KOLKATA-700023, KOLKATA, F UR Hospital, Basirhat KHATOON WEST BENGAL, 700023 Health District DULAL DEBNATH, C/O-DULAL MADHUSMITA Birpara State General 5 DEBNATH,PIJUPARA NAGARBERA,PO- F UR DEVI Hospital, Alipurduar NAGARBERA, , KAMRUP, OTHER, 781127 SWAPAN KUMAR PATI, VILL - IPGMER & SSKM SUBHASREE KALINDIPUR, P.O - PANSKURA RS, P.S - 6 F UR Hospital, Kolkata PATI PANSKURA, PURBA MEDINIPUR, WEST (Trauma Care Centre) BENGAL, 721152 SUBRATA CHAKRABORTY, FLAT NO- 4C,SAPTORSHI TOWER,164 MOHISHILA Dhupguri Rural SOHINI 7 COLONY 1NO, NEAR BOYS SCHOOL F UR Hospital, Dhupguri, CHAKRABORTY P.O. -

Ayodhya Page:- 1 Cent-Code & Name Exam Sch-Status School Code & Name #School-Allot Sex Part Group 1003 Canossa Convent Girls Inter College Ayodhya Buf

DATE:27-02-2021 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 **** FINAL CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT **** DIST-CD & NAME :- 62 AYODHYA PAGE:- 1 CENT-CODE & NAME EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA BUF HIGH BUF 1001 SAHABDEENRAM SITARAM BALIKA I C AYODHYA 73 F HIGH BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 225 F 298 INTER BUF 1002 METHODIST GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 56 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 109 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 111 F SCIENCE INTER CUM 1091 DARSGAH E ISLAMI INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 53 F ALL GROUP 329 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 627 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA AUF HIGH AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 40 F HIGH CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 11 F HIGH CRM 1140 SARDAR BHAGAT SINGH HS BARAIPARA DULLAPUR AYODHYA 20 F HIGH CRM 1208 M D M N ARYA HSS R N M G GANJ AYODHYA 7 F HIGH CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 32 F HIGH CRM 1269 S S M HSS K G ROAD GOSHAINGANJ AYODHYA 26 F HIGH CRM 1276 IMAMIA H S S AMSIN AYODHYA 15 F HIGH AUF 5004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 18 F 169 INTER AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 43 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1075 MADHURI GIRLS I C AMSIN AYODHYA 91 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 7 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1138 AMIT ALOK I C BODHIPUR AMSIN AYODHYA 96 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 74 -

Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands In

Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 Government of India PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi (March, 2007) Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012) CONTENTS Constitution order for Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves and Wetlands 1-6 Chapter 1: Islands 5-24 1.1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5-17 1.2 Lakshwadeep Islands 18-24 Chapter 2: Coral reefs 25-50 Chapter 3: Mangroves 51-73 Chapter 4: Wetlands 73-87 Chapter 5: Recommendations 86-93 Chapter 6: References 92-103 M-13033/1/2006-E&F Planning Commission (Environment & Forests Unit) Yojana Bhavan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi, Dated 21st August, 2006 Subject: Constitution of the Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves & Wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007- 2012). It has been decided to set up a Task Force on Islands, corals, mangroves & wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan. The composition of the Task Force will be as under: 1. Shri J.R.B.Alfred, Director, ZSI Chairman 2. Shri Pankaj Shekhsaria, Kalpavriksh, Pune Member 3. Mr. Harry Andrews, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust , Tamil Nadu Member 4. Dr. V. Selvam, Programme Director, MSSRF, Chennai Member Terms of Reference of the Task Force will be as follows: • Review the current laws, policies, procedures and practices related to conservation and sustainable use of island, coral, mangrove and wetland ecosystems and recommend correctives. -

Statistical Diary, Uttar Pradesh-2020 (English)

ST A TISTICAL DIAR STATISTICAL DIARY UTTAR PRADESH 2020 Y UTT AR PR ADESH 2020 Economic & Statistics Division Economic & Statistics Division State Planning Institute State Planning Institute Planning Department, Uttar Pradesh Planning Department, Uttar Pradesh website-http://updes.up.nic.in website-http://updes.up.nic.in STATISTICAL DIARY UTTAR PRADESH 2020 ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS DIVISION STATE PLANNING INSTITUTE PLANNING DEPARTMENT, UTTAR PRADESH http://updes.up.nic.in OFFICERS & STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE PUBLICATION 1. SHRI VIVEK Director Guidance and Supervision 1. SHRI VIKRAMADITYA PANDEY Jt. Director 2. DR(SMT) DIVYA SARIN MEHROTRA Jt. Director 3. SHRI JITENDRA YADAV Dy. Director 3. SMT POONAM Eco. & Stat. Officer 4. SHRI RAJBALI Addl. Stat. Officer (In-charge) Manuscript work 1. Dr. MANJU DIKSHIT Addl. Stat. Officer Scrutiny work 1. SHRI KAUSHLESH KR SHUKLA Addl. Stat. Officer Collection of Data from Local Departments 1. SMT REETA SHRIVASTAVA Addl. Stat. Officer 2. SHRI AWADESH BHARTI Addl. Stat. Officer 3. SHRI SATYENDRA PRASAD TIWARI Addl. Stat. Officer 4. SMT GEETANJALI Addl. Stat. Officer 5. SHRI KAUSHLESH KR SHUKLA Addl. Stat. Officer 6. SMT KIRAN KUMARI Addl. Stat. Officer 7. MS GAYTRI BALA GAUTAM Addl. Stat. Officer 8. SMT KIRAN GUPTA P. V. Operator Graph/Chart, Map & Cover Page Work 1. SHRI SHIV SHANKAR YADAV Chief Artist 2. SHRI RAJENDRA PRASAD MISHRA Senior Artist 3. SHRI SANJAY KUMAR Senior Artist Typing & Other Work 1. SMT NEELIMA TRIPATHI Junior Assistant 2. SMT MALTI Fourth Class CONTENTS S.No. Items Page 1. List of Chapters i 2. List of Tables ii-ix 3. Conversion Factors x 4. Map, Graph/Charts xi-xxiii 5. -

Madhya Pradesh Administrative Divisions 2011

MADHYA PRADESH ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS 2011 U T KILOMETRES 40 0 40 80 120 T N Porsa ! ! ! Ater Ambah Gormi Morena ! P Bhind P A ! BHIND MORENA ! Mehgaon! A ! Ron Gohad ! Kailaras Joura Mihona Sabalgarh ! ! P ! ! Gwalior H ! Dabra Seondha ! GWALIOR ! Lahar R Beerpur Vijaypur ! ! Chinour Indergarh Bhitarwar DATIA Bhander ! T SHEOPUR Datia ! Sheopur Pohri P P P ! ! Narwar R Karahal Shivpuri A ! Karera Badoda P SHIVPURI ! S ! N!iwari D D ! ! Pichhore Orchh!a Gaurihar ! D Nowgong E ! Prithvipur Laundi Kolaras ! Chandla Jawa ! D TIKAMGARHPalera ! ! ! ! Teonthar A ! ! Jatara ! ! Maharajpur Khaniyadhana ! Sirmour Bad!arwas Mohangarh P ! Ajaigarh ! Naigarhi S ! ! Majhgawan ! REWA ! ! ! Chhatarpur Rajnagar ! Semaria ! ! Khargapur Birsinghpur Mangawan Hanumana Singoli Bamori Isagarh Chanderi ! CHHATARPUR (Raghurajnagar) ! Guna ! P Baldeogarh P Kotar (Huzur) Maugan!j Shadhora Panna P ! Raipur-Karchuliyan ! Chitrangi ! ASHOKNAGAR Tikamgarh Bijawar ! Rampur P ! J Jawad P ! ! DevendranagarNago!d !Gurh Sihawal ! ! P Baghelan ! Churhat GUNA Bada Malhera ! ! P H NEEMUCH Bhanpura Ashoknagar ! !Gunnor (Gopadbanas) ! I Raghogarh N Ghuwara D ! SATNA I ! ! A P ! Manasa ! Mungaoli PANNA Unchahara !Amarpatan Rampur Naikin Neemuch ! ! ! Amanganj SINGRAULI ! Aron ! Shahgarh Buxwaha ! Pawai SIDHI ! Kumbhraj Bina ! ! Ram!nagar !Majhauli Deosar Jiran Malhargarh Garoth Hatta ! ! Kurwai ! Shahnagar Maihar P ! ! Maksoodanga!rh Malthon Batiyagarh ! MANDSAUR ! ! ! Beohari Singrauli Mandsaur Shamgarh Jirapur ! Chachaura Lateri Sironj Khurai Raipura ! ! ! A ! P ! ! ! ! -

Copy of PSC Address.Xlsx

Address of Program Study Centers S.N Districts Name of Institutes Address Contact No 1 Agra District Women Hospital-Agra Shahid Bhagatsingh Rd, Rajamandi Crossing, Bagh Muzaffar 0562 226 7987 Khan, Mantola, Agra, Uttar Pradesh 282002 2Aligarh District Women Hospital-Aligarh Rasal Ganj Rd, City, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh 202001 3 Pt. DDU District Combined Hospital-Aligarh Ramghat Rd, Near Commissioner House, Quarsi, Aligarh, 0571 274 1446 Uttar Pradesh 202001 4 Prayagraj District Women Hospital-Prayagraj 22/26, Kanpur - Allahabad Hwy, Roshan Bagh, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh 211003 5 Azamgarh District Women Hospital-Azamgarh Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg, Balrampur, Harra Ki Chungi, 091208 49999 Sadar, Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh 276001 6 Bahraich District Male Hospital-Bahraich Ghasiyaripura, Friganj, Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh 271801 094150 36818 7 Bareilly District Women Hospital-Bareilly Civil Lines, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh 243003 0581 255 0009 8 Basti District Women Hospital-Basti Ladies hospital, Kateshwar Pur, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 272001 9 Gonda District Women Hospital-Gonda Khaira, Gonda, Uttar Pradesh 271001 11 Etawah District Male Hospital-Etawah Civil Lines, Etawah, Uttar Pradesh 206001 099976 04403 12 Ayodhya District Women Hospital-Ayodhya Fatehganj Rikabganj Road, Rikaabganj, Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh 224001 13 GB Nagar Combined Hospital-GB Nagar C-18, Service Rd, C-Block, Sector 31, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201301 14 Ghaziabad District Combined Hospital, Sanjay Nagar- District Combined Hospital, Mansi Vihar, Sector 23, Sanjay Ghaziabad Nagar, Ghaziabad,