1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kalahandi Forest Division Reserved Forests Name of Range Name Of

Kalahandi Forest Division Reserved Forests Name of range Name of Blocks Area in Hectares Govt. notification Madanpur –Rampur Tapranga 6839 Urladani 10737 Benaguda 5087 Sunamukhi 2399 Dengen 496 Jerka 1006 Turchi 246 Sadel”A” 282 Sadel “B” 320 Satami 1873 Telen 2630 Lumersingha 119 Bhatel 37 Sripali 46 Biswanathpur Champadeipur 67 Jhimri 1419 Raul 655 Bori 1448 Patraguda 179 Dhepaguda 464 Sargiguda 767 Kidding 688 Samjhola 893 Niyamgiri 2007 Porgel 1762 Dulma 565 Nachiniguda 1154 Jalkrida 1775 Machul 967 Benbhata 1657 Pahadpadar 1670 Kesinga Nangalguda 1474 Kamel 176 Karladanger 375 Madakhola’A’ 659 Kerbandi 1108 Bazargarh 7911 Kadalighati 1655 Narla 1293 Bhawanipatna Dhangada-Dhangidi 250 Kanamanjure 1932 Sinang 1178 Kutrukhai 315 Bhalu 60 Pordhar 704 Jugsaipatna 2084 Nehela 3956 Karlapat 7077 Alma 1404 Madakhol ‘B’ 645 Brahmani 5768 Dhanupanchan 740 Junagarh Ghana 3094 Kelia 232 Jalabandha ‘A’ 40 Jalabandha ‘B’ 28 Jalabandha ‘C’ 76 Pariagarh 810 Panigaon 508 Kandul 95 Barjan 355 Jharbandha 317 Sahajkhol 12521 Raktaboden 180 Talc hirka 140 Bhalujore 48 Balagaon 64 Dulkibandha 47 Ninaguda 71 Singhari 5887 Udayagiri 1197 Jerka 2754 Kegaon Daka 343 Kumkot 5000 Chura ‘A’ 7732 Chura ‘B’ 2333 Gujia 339 Lini 139 Ghatual 275 Adabori 921 Bisbhurni 212 Nageswar 3154 Thuamul-Rampur Thakuranipadar 83 Goyalkhoj 234 Kuspari 131 Khakes 74 Ampadar 94 Sulbadi 11 Baghmari 26 Arkhapedi 66 Kucharighati 33 Uperchikra 69 Ranipadar 62 Benakhamar 450 Kadokhaman 78 Bijaghati 38 Proposed reserved forest Name of the Range Name of the blocks Area in Hectors Notification with date I .Bhawanipatna Sagada 1069 Khandual 450.73 46268/R dt.02.06.75 Jugsaipatna Extn. -

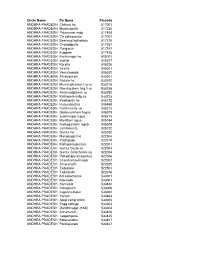

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Category: UR-MEN

FINAL LIST OF CANDIDATE DIST:-NUAPADA Event: - BROAD JUMP, HIGH JUMP, 1.6 KM RUN, ROPE CLIMBING, SWIMMING Category: UR-MEN Broad Jump Swimmi BS Qualified Sl Full Postal Rope Running 2.75 High ng Driving Disqualifi SL Name of the candidate Father's Name /Disquali No address Climbing 1.6 Kms. Mtr. Jump ( 40 Test ed in NO. fied (Minimu Mtrs) m) Rajesh Ranjan Dash At/PO. Tukula, PS. 1 Saroj Kumar Dash Khariar, Dist. 6 6 5 8 Q Q 1 Nuapada Dhirendra Dash At/Po. Tukula, PS. 2 Kailash Chandra Dash Khariar, Dist. 6 4 3 2 Q Q 2 Nuapada At/PO. Tipu Sultan Nangalbord, PS. 3 Abdul Satar DQ ABSENT Sinapali, Dist. 3 Nuapada At. Mahulpada, Ratna Mohan Hota ROPE PO. Chatiaguda, 4 Prasanna Hota NIL DQ CLIMBIN PS. Sinapali, Dist. G 4 Nuapada Kamal Kumar Dash At/Po. Tukula, PS. 5 Kalia Dash Khariar, DQ ABSENT 5 Dist.Nuapada Kanha Charan Dash At/Po. Tukula, PS. 6 Madhusudan Dash Khariar, Dist. DQ ABSENT 6 Nuapada Bikash Kumar Dash At/Po. Tukula, 7 Ballav Dash PS. Khariar, Dist. DQ HEIGHT 7 Nuapada Akash Kumar Dash At/Po. Tukula, 1.6 KMS 8 Dhruba Charan Dash PS. Khariar, Dist. 6 NIL 6 3 DQ RUN 8 Nuapada Prakash Chandra Mund At/PO. Bargaon, 9 Satyanand Mund PS. Khariar, Dist. DQ ABSENT 9 Nuapada Akash Nayak At/Po. Bargaon, 10 Manoj Nayak PS. Khariar, Dist. 6 4 5 6 Q Q 10 Nuapada Akash Joshi At/Po. Bhela, ROPE 11 Ambarnath Joshi PS. Komna, Dist. NIL DQ CLIMBIN 11 Nuapada G At. -

Orissa Burning the Sinister Anti-Christian Pogrom in Orissa

1 ORISSA BURNING THE SINISTER ANTI-CHRISTIAN POGROM IN ORISSA. WHAT THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA ISN'T TELLING YOU ABOUT ONGOING TO RTURE AND KILLING OF CHRISTIANS THERE. Monday, September 1, 2008 Fresh Violence: Atleast 4 More Churches Burnt At Least Four More Churches Burnt as Violence Continues to Spread in Orissa Christians gather inside a shelter at Raikia village in Orissa August 31, 2008. Situation Under Whose Control? Despite all "situation under control" assurances, violence continues to spread in Orissa. Reuters reports: Hindu mobs have burnt at least four more churches in Orissa, officials said on Monday, as religious violence appeared to spread. Thousands of people, mostly Christians, have taken shelter in makeshift camps, where Hindu mobs went on the rampage last week after a Hindu leader was killed. Last week officials said the violence appeared to be abating after Hindu and 2 Christian leaders called for calm, but over the weekend it spread to new parts of the state. Mobs set fire to four churches in the districts of Koraput and Rayagada, Orissa's Director General of Police, Gopal Chandra Nanda, told Reuters. Two churches and several houses were also burnt in the Kandhamal district, the epicentre of the tension, despite a curfew imposed in most of its towns, one of the state's leading newspapers, The Samaja, reported on Monday. POSTED BY ORISSA BURNING AT 3:07 PM 0 COMMENTS LINKS TO THIS POST LABELS: NEWS AND ANALYSIS , PICTURES FIACONA Protests at the UN HQ in New York FIACONA Stages Protest Outside United Nations Headquarters Members of the Federation of Indian American Christian Organisations of North America stage a protest outside the United Nations headquarters. -

Formation and Activities of the Utkal Provincial Krushak Sangha in Colonial Odisha (1935-38)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 3 Issue 12 ǁ December. 2014 ǁ PP.46-52 Formation and Activities of the Utkal Provincial Krushak Sangha in Colonial Odisha (1935-38) Amit Kumar Nayak PhD Research Scholar, P.G. Department of History, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. ABSTRACT : The peasants of Odisha came within the ambit of colonial capitalistic economic system after British conquered Odisha in 1803.Up to the end of the Civil Dis-obedience movement, the peasants in Odisha yet remained backward, retrogressive, unorganised and feudal in nature . Out of different circumstances socialism started to germinate in and later on dominated the post-Civil Disobedience movement phase Odisha.The newly indoctrinated socialist leaders took up peasants‟ cause and organised them against colonial hegemonic rule in different issues by organising a special peasants‟ organization in pan-Odishan basis. So, this article tries to locate the efforts of the socialist leaders vis-a-vis the peasants through Utkal Provincial Krushak Sangha. It also endeavours to assess the overall activities of that organisation, its tactics in mobilizing peasants in colonial Odisha from 1935 to 1938.Besides, this article also tries to present how the Utkal Provincial Krushaka Sangha was formed and how it worked as a platform for the peasants of odisha in co-ordinating, mobilising, educating and organising the agrarian community in 1930s and 1940s.. KEYWORDS : Agrarian, Krushaka , Movement, Rebellion , Sangha, , Socialist ,Utkal I. INTRODUCTION Peasants (English term for the Odia word Krushak), being a segment in the complex capitalistic farming system, are destined to fulfill its legitimate rights, according to Karl Marx, through prolonged ‗class struggle‘. -

Health Centers

LIST OF HEALTH CENTERS OF NUAPADA DISTRICT SL.No Name of the Block Name of the CHC Name of the Sector Name of the SC Name of the PHC(N) 1 Beltukuri PHC(N), BELTUKRI 2 Beltukri Bisora 3 Bhaleswar 4 Biromal PHC(N), BIROMAL 5 Jampani Biromal 6 Kuliabandha 7 Kodomeri 8 Darlimunda PHC(N) ,DARLIMUNDA 9 Saipala 10 Maulibhata Darlimunda 11 Tanwat 12 Godfula NUAPADA CHC, KHARIAR ROAD 13 Kotenchuan 14 Dharambandha PHC(N),DHARAMBANDHA 15 Motanuapada 16 Kendubahara Dharambandha 17 Amanara 18 Sarabong 19 Maraguda 20 Parkod CHC Khariar road 21 Jenjera 22 Khariar road Amsena 23 Gotma 24 Khariar Road 25 Tarbod PHC(N), TARBOD 26 Jatgarh 27 Darlipada 28 Turbod Siallati 29 Kurumpuri 30 Samarsingh 31 Lakhna 32 Budhikomna PHC(N), BUDHHIKOMNA Budhikomna CHC,KOMNA & CHC , KOMNA BHELLA 33 Kandetara 34 Budhikomna Nuagaon 35 Gandamer PHC(N) ,DARLIPADA CHC,KOMNA & CHC , 36 KOMNA Suklimundi BHELLA 37 Bhella PHC(N),SUNABEDA 38 Agren 39 Rajna Bhela 40 Chhata 41 Bisibahal 42 Sunabeda 43 Konabira 44 Pendrawan 45 Komna Tikrapada 46 Udyanbandh 47 Komna 48 Duajhar PHC(N),DUAJHAR 49 Kotamal 50 Nehena 51 DUAJHAR Kirkita 52 Dhanksar 53 Birighat 54 Lanji PHC(N), TUKLA 55 Bargaon 56 Khudpej KHARIAR CHC,KHARIAR 57 Bargaon Badmaheswar 58 Bhojpur PHC(N), LANJI 59 Bhuliasikuan 60 Amlapali 61 Lachhipur 62 Badi Khariar 63 Khasbahal 64 Khariar 65 Tukla 66 Sinapali PHC(N) ,LIAD Sinapali SINAPALI CHC,SINAPALI 67 Bramhaniguda 68 Bargaon Sinapali 69 Gandabahali 70 Godal 71 Singhjhar 72 Hatibandha PHC(N),HATIBANDHA 73 Chalna Hatibandha 74 Bharuamunda 75 SINAPALI CHC,SINAPALI Makhapadar 76 Timanpur PHC(N), TIMANPUR 77 Timnapur Niljee 78 Gorla 79 Kendumunda 80 Badibahal Kendumunda 81 Kuliadunguri 82 Nagalbod 83 Boden Bhainsadani PHC(N) Bhainsadani 84 Boden 85 BODEN Boirgaon 86 BODEN Damjhar PHC(N),DAMJHAR 87 BODEN Nagpada 88 BODEN Sunapur 89 BODEN Karlakot 90 BODEN Khaira 91 BODEN Karangamal Karngamal PHC(N), KARANGAMAL CHC,BODEN 92 BODEN Kulekela 93 BODEN Farsara 94 BODEN Larka 95 BODEN Litisargi 96 BODEN Rokal 97 BODEN 98 BODEN. -

Odisha As a Multicultural State: from Multiculturalism to Politics of Sub-Regionalism

Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences Volume VII, No II. Quarter II 2016 ISSN: 2229 – 5313 ODISHA AS A MULTICULTURAL STATE: FROM MULTICULTURALISM TO POLITICS OF SUB-REGIONALISM Artatrana Gochhayat Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Sree Chaitanya College, Habra, under West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal, India ABSTRACT The state of Odisha has been shaped by a unique geography, different cultural patterns from neighboring states, and a predominant Jagannath culture along with a number of castes, tribes, religions, languages and regional disparity which shows the multicultural nature of the state. But the regional disparities in terms of economic and political development pose a grave challenge to the state politics in Odisha. Thus, multiculturalism in Odisha can be defined as the territorial division of the state into different sub-regions and in terms of regionalism and sub- regional identity. The paper attempts to assess Odisha as a multicultural state by highlighting its cultural diversity and tries to establish the idea that multiculturalism is manifested in sub- regionalism. Bringing out the major areas of sub-regional disparity that lead to secessionist movement and the response of state government to it, the paper concludes with some suggestive measures. INTRODUCTION The concept of multiculturalism has attracted immense attention of the academicians as well as researchers in present times for the fact that it not only involves the question of citizenship, justice, recognition, identities and group differentiated rights of cultural disadvantaged minorities, it also offers solutions to the challenges arising from the diverse cultural groups. It endorses the idea of difference and heterogeneity which is manifested in the cultural diversity. -

List of 253 Journalists Who Lost Their Lives Due to COVID-19. (Updated Until May 19, 2021)

List of 253 Journalists who lost their lives due to COVID-19. (Updated until May 19, 2021) Andhra Pradesh 1 Mr Srinivasa Rao Prajashakti Daily 2 Mr Surya Prakash Vikas Parvada 3 Mr M Parthasarathy CVR News Channel 4 Mr Narayanam Seshacharyulu Eenadu 5 Mr Chandrashekar Naidu NTV 6 Mr Ravindranath N Sandadi 7 Mr Gopi Yadav Tv9 Telugu 8 Mr P Tataiah -NA- 9 Mr Bhanu Prakash Rath Doordarshan 10 Mr Sumit Onka The Pioneer 11 Mr Gopi Sakshi Assam 12 Mr Golap Saikia All India Radio 13 Mr Jadu Chutia Moranhat Press club president 14 Mr Horen Borgohain Senior Journalist 15 Mr Shivacharan Kalita Senior Journalist 16 Mr Dhaneshwar Rabha Rural Reporter 17 Mr Ashim Dutta -NA- 18 Mr Aiyushman Dutta Freelance Bihar 19 Mr Krishna Mohan Sharma Times of India 20 Mr Ram Prakash Gupta Danik Jagran 21 Mr Arun Kumar Verma Prasar Bharti Chandigarh 22 Mr Davinder Pal Singh PTC News Chhattisgarh 23 Mr Pradeep Arya Journalist and Cartoonist 24 Mr Ganesh Tiwari Senior Journalist Delhi 25 Mr Kapil Datta Hindustan Times 26 Mr Yogesh Kumar Doordarshan 27 Mr Radhakrishna Muralidhar The Wire 28 Mr Ashish Yechury News Laundry 29 Mr Chanchal Pal Chauhan Times of India 30 Mr Manglesh Dabral Freelance 31 Mr Rajiv Katara Kadambini Magazine 32 Mr Vikas Sharma Republic Bharat 33 Mr Chandan Jaiswal Navodaya Times 34 Umashankar Sonthalia Fame India 35 Jarnail Singh Former Journalist 36 Sunil Jain Financial Express Page 1 of 6 Rate The Debate, Institute of Perception Studies H-10, Jangpura Extension, New Delhi – 110014 | www.ipsdelhi.org.in | [email protected] 37 Sudesh Vasudev -

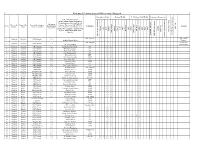

Namebased Training Status of DP Personnel

Namebased Training status of DP Personnel - Nayagarh Reproductive Health Maternal Health Neo Natal and Child Health Programme Management Name of Health Personnel (ADMO, All Spl., MBBS, AYUSH MO, Central Drugstore MO, Lab Tech.- all Category of Name of the Name of the Name of the institution Category, Pharmacist, SNs, LHV, H.S Sl. No. the institutions Designation Remarks District. Block (Mention only DPs) (M)), ANM, Adl. ANM, HW(M), Cold (L1, L2, L3) Chain Tech. Attendant- OT, Labor Room Trg IMEP BSU NSV NRC MTP IYCF LSAS IUCD NSSK FBNC EmOC DPHM IMNCI Minilap BEmOC RTI/STI PPIUCD & OPD. DPMU Staff, BPMU Staff, FIMNCI Induction Induction training PMSU Trg. PMSU IMNCI (FUS) IMNCI Sweeper (21SAB days) Fin. Mgt Trg. (Accounts trg) PGDPHM (Full Time) PGDPHSM (E-learning) Laparoscopic sterilization 1 atMDP reputed institution Asst. Surgeon 1 1 1 1 PG At SCB 1 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Dr Bijay Kumar Meher Cuttack Asst. Surgeon 1 1 Transfert to 2 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Dr Prasanta Dash Nabarangapur 3 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Smt.Sudiptarani Nanda SN 1 1 1 1 4 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Miss Sabita Kunar SN 1 1 1 1 5 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Miss Sabitri Dash SN 1 1 1 1 6 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Mrs. Rasmirani Lal SN 1 1 1 1 7 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Mrs Kabita Jena LHV 1 1 1 1 8 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Mrs.Jayanti Samartha ANM 1 1 1 1 9 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Swarnalata Joshi SN 1 10 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Taposwani Panda ANM 1 1 11 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Nibedita Baral SN 12 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Jyoti Manjari Baitharu SN 13 Nuapada Sinapali Liad PHC(N) L1 Dr Dipdil Sahoo Asst. -

IEE: India: Rural Roads Sector II Investment Program (Project 4

Environmental Assessment Report Initial Environmental Examination for Orissa Project Number: 37066 June 2009 India: Rural Roads Sector II Investment Program (Project 4) Prepared by [Author(s)] [Firm] [City, Country] Prepared by Ministry of Rural Development for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Prepared for [Executing Agency] [Implementing Agency] The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. RURAL ROADS SECTOR II INVESTMENT PROGRAMME ORISSA, INDIA INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION REPORT BATCH III: 1498.58 Km of Rural Roads June 2009 MINISTRY OF RURAL DEVELOPMENT Acronyms and Abbreviations ADB : Asian Development Bank BIS : Bureau of Indian Standards CD : Cross Drainage CGWB : Central Ground Water Board CO : Carbon Monoxide COI : Corridor of Impact DM : District Magistrate EA : Executing Agency EAF : Environment Assessment Framework ECOP : Environmental Codes of Practice EIA : Environmental Impact Assessment EMAP : Environmental Management Action Plan EO : Environmental Officer FEO : Field Environmental Officer FGD : Focus Group Discussion FFA : Framework Financing Agreement GOI : Government of India GP : Gram Panchayat GSB : Granular Sub Base HC : Hydro Carbon IA : Implementing Agency -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

The National

THE NATIONAL Media Partner Supported by Tuesday, December 15, 2020 Live on YouTube 53 Foreword It gives us immense pleasure to share with you the event brochure of the 10th edition of the Laadli Media and Advertising Awards for Gender Sensitivity 2020. It was a very exciting nine months for us since we announced the call for entries in March 2020. The anxiety and excitement of receiving entries during the Covid‐19 times, the shortlisting process, the animated discussions at jury meetings and the new learning of organizing an online event. What an amazing experience it was! The icing on the cake was the very act of reading and watching diverse content and the feeling that all was not lost and that there is hope for a strong and meaningful media emerging from the current crisis. The online publications, the OTT and the Social Media platforms seem to be providing the much needed space and time to journalists and creative content producers to work on topics and themes which would perhaps not be accepted by a mainstream publication or channel. The freedom from commercial concerns seems to be liberating in a sense. Yet, on the lip side was the using of social media by organized mobs of netizens, acting as vigilantes, and trying to inluence and regulate free expression through threats and trolls. It was heartening to note that young journalists writing for regional language paper's like Gaon Connection were doing amazing and much needed ield‐based reporting. Reading about the Bhawaiyyas, sexual exploitation of women and children in tea gardens, the troubles and travails of women traficked for marriage to Haryana was enlightening.