Forestry Commission Bulletin: Forestry Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thematic Forest Dictionary

Elżbieta Kloc THEMATIC FOREST DICTIONARY TEMATYCZNY SŁOWNIK LEÂNY Wydano na zlecenie Dyrekcji Generalnej Lasów Państwowych Warszawa 2015 © Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych ul. Grójecka 127 02-124 Warszawa tel. 22 18 55 353 e-mail: [email protected] www.lasy.gov.pl © Elżbieta Kloc Konsultacja merytoryczna: dr inż. Krzysztof Michalec Konsultacja i współautorstwo haseł z zakresu hodowli lasu: dr inż. Maciej Pach Recenzja: dr Ewa Bandura Ilustracje: Bartłomiej Gaczorek Zdjęcia na okładce Paweł Fabijański Korekta Anna Wikło ISBN 978-83-63895-48-8 Projek graficzny i przygotowanie do druku PLUPART Druk i oprawa Ośrodek Rozwojowo-Wdrożeniowy Lasów Państwowych w Bedoniu TABLE OF CONTENTS – SPIS TREÂCI ENGLISH-POLISH THEMATIC FOREST DICTIONARY ANGIELSKO-POLSKI TEMATYCZNY SŁOWNIK LEÂNY OD AUTORKI ................................................... 9 WYKAZ OBJAŚNIEŃ I SKRÓTÓW ................................... 10 PLANTS – ROŚLINY ............................................ 13 1. Taxa – jednostki taksonomiczne .................................. 14 2. Plant classification – klasyfikacja roślin ............................. 14 3. List of forest plant species – lista gatunków roślin leśnych .............. 17 4. List of tree and shrub species – lista gatunków drzew i krzewów ......... 19 5. Plant morphology – morfologia roślin .............................. 22 6. Plant cells, tissues and their compounds – komórki i tkanki roślinne oraz ich części składowe .................. 30 7. Plant habitat preferences – preferencje środowiskowe roślin -

Planting Power ... Formation in Portugal.Pdf

Promotoren: Dr. F. von Benda-Beckmann Hoogleraar in het recht, meer in het bijzonder het agrarisch recht van de niet-westerse gebieden. Ir. A. van Maaren Emeritus hoogleraar in de boshuishoudkunde. Preface The history of Portugal is, like that of many other countries in Europe, one of deforestation and reafforestation. Until the eighteenth century, the reclamation of land for agriculture, the expansion of animal husbandry (often on communal grazing grounds or baldios), and the increased demand for wood and timber resulted in the gradual disappearance of forests and woodlands. This tendency was reversed only in the nineteenth century, when planting of trees became a scientifically guided and often government-sponsored activity. The reversal was due, on the one hand, to the increased economic value of timber (the market's "invisible hand" raised timber prices and made forest plantation economically attractive), and to the realization that deforestation had severe impacts on the environment. It was no accident that the idea of sustainability, so much in vogue today, was developed by early-nineteenth-century foresters. Such is the common perspective on forestry history in Europe and Portugal. Within this perspective, social phenomena are translated into abstract notions like agricultural expansion, the invisible hand of the market, and the public interest in sustainably-used natural environments. In such accounts, trees can become gifts from the gods to shelter, feed and warm the mortals (for an example, see: O Vilarealense, (Vila Real), 12 January 1961). However, a closer look makes it clear that such a detached account misses one key aspect: forests serve not only public, but also particular interests, and these particular interests correspond to specific social groups. -

Forest Measurements for Natural Resource Professionals, 2001 Workshop Proceedings

Natural Resource Network Connecting Research, Teaching and Outreach 2001 Workshop Proceedings Forest Measurements for Natural Resource Professionals Caroline A. Fox Research and Demonstration Forest Hillsborough, NH Sampling & Management of Coarse Woody Debris- October 12 Getting the Most from Your Cruise- October 19 Cruising Hardware & Software for Foresters- November 9 UNH Cooperative Extension 131 Main Street, 214 Nesmith Hall, Durham, NH 03824 The Caroline A. Fox Research and Demonstration Forest (Fox Forest) is in Hillsborough, NH. Its focus is applied practical research, demonstration forests, and education and outreach for a variety of audiences. A Workshop Series on Forest Measurements for Natural Resource Professionals was held in the fall of 2001. These proceedings were prepared as a supplement to the workshop. Papers submitted were not peer-reviewed or edited. They were compiled by Karen P. Bennett, Extension Specialist in Forest Resources and Ken Desmarais, Forester with the NH Division of Forests and Lands. Readers who did not attend the workshop are encouraged to contact authors directly for clarifications. Workshop attendees received additional supplemental materials. Sampling and Management for Down Coarse Woody Debris in New England: A Workshop- October 12, 2001 The What and Why of CWD– Mark Ducey, Assistant Professor, UNH Department of Natural Resources New Hampshire’s Logging Efficiency– Ken Desmarais, Forester/ Researcher, Fox State Forest The Regional Level: Characteristics of DDW in Maine, NH and VT– Linda Heath, -

Methodology for Afforestation And

METHODOLOGY FOR THE QUANTIFICATION, MONITORING, REPORTING AND VERIFICATION OF GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS REDUCTIONS AND REMOVALS FROM AFFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION OF DEGRADED LAND VERSION 1.2 May 2017 METHODOLOGY FOR THE QUANTIFICATION, MONITORING, REPORTING AND VERIFICATION OF GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS REDUCTIONS AND REMOVALS FROM AFFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION OF DEGRADED LAND VERSION 1.2 May 2017 American Carbon Registry® WASHINGTON DC OFFICE c/o Winrock International 2451 Crystal Drive, Suite 700 Arlington, Virginia 22202 USA ph +1 703 302 6500 [email protected] americancarbonregistry.org ABOUT AMERICAN CARBON REGISTRY® (ACR) A leading carbon offset program founded in 1996 as the first private voluntary GHG registry in the world, ACR operates in the voluntary and regulated carbon markets. ACR has unparalleled experience in the development of environmentally rigorous, science-based offset methodolo- gies as well as operational experience in the oversight of offset project verification, registration, offset issuance and retirement reporting through its online registry system. © 2017 American Carbon Registry at Winrock International. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced, displayed, modified or distributed without express written permission of the American Carbon Registry. The sole permitted use of the publication is for the registration of projects on the American Carbon Registry. For requests to license the publication or any part thereof for a different use, write to the Washington DC address listed above. -

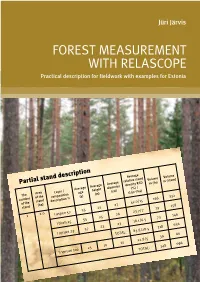

Forest Measurement with Relascope Practical Description for Fieldwork with Examples for Estonia

Jüri Järvis FOREST MEASUREMENT Practical descriptionWITH for fieldwork RELASCOPE with examples for Estonia Partial stand description Average The Area Layer / Average Average Average relative stand number of the Volume Volume composition age height diameter density RSD of the stand m3/ha m3/stand description % (y) (m) (cm) (%) / stand (ha) G (m2/ha) 1 2.0 I aspen 52 55 25 27 42.0/15 166 332 I birch 25 55 25 26 23.7/7 79 158 I spruce 23 57 23 23 18.1/6.5 73 146 TOTAL: 83.8/28.5 318 636 II spruce 100 25 10 10 22.8/5 30 60 TOTAL: 348 696 The relascope and relascope measurement was invented Title of the original: Metsa relaskoopmõõtmine. Puistu rinnaspindala, täiuse ja mahu and introduced by Austrian forest scientist Walter Bitterlich määramine lihtrelaskoopi kasutades. (Bitterlich 1947, 1948). The method is widely used because II täiendatud trükk (2010). it is simple, handy and quick. However, the method is less accurate when compared to cross-callipering forest Translation into English 2013; first printed 2006. measurement. It is used for the preliminary assessment of timber supply in a tree stand 1. © Jüri Järvis 2010; 2013. Simplified relascope is also called “simple relascope”, All rights reserved. “angle-counter”, “angle-gauge” or “angle-template”. So- called true relascope or mirror-relascope is a device that can automatically adjust its measured values according Consultants: Ahto Kangur, Allan Sims, Allar Padari, Andres Kiviste, Artur Nilson, to the slope of the ground (photo 1). Mart Vaus (Estonian University of Life Sciences, Institute of Forestry and Rural Engineering, Electronic relascope can be used instead of traditional Photo 1. -

Assessing Precision in Conventional Field Measurements of Individual Tree Attributes

Communication Assessing Precision in Conventional Field Measurements of Individual Tree Attributes Ville Luoma 1,4,*, Ninni Saarinen 1,4, Michael A. Wulder 2, Joanne C. White 2, Mikko Vastaranta 1,4, Markus Holopainen 1,4 and Juha Hyyppä 3,4 1 Department of Forest Sciences, University of Helsinki, P.O.Box 27 (Latokartanonkaari 7), 00014 Helsinki, Finland; ninni.saarinen@helsinki.fi (N.S.); mikko.vastaranta@helsinki.fi (M.V.); markus.holopainen@helsinki.fi (M.H.) 2 Canadian Forest Service (Pacific Forestry Centre), Natural Resources Canada, 506 West Burnside Road, Victoria, BC V8Z 1M5, Canada; [email protected] (M.A.W.); [email protected] (J.C.W.) 3 Department of Remote Sensing and Photogrammetry, Finnish Geospatial Research Institute FGI, National Land Survey, Geodeetinrinne 2, 04310 Masala, Finland; juha.hyyppa@nls.fi 4 Centre of Excellence in Laser Scanning Research, Finnish Geospatial Research Institute FGI, National Land Survey, 04310 Masala, Finland * Correspondence: ville.luoma@helsinki.fi; Tel.: +358-44-047-6070 Academic Editor: Timothy A. Martin Received: 16 December 2016; Accepted: 4 February 2017; Published: 8 February 2017 Abstract: Forest resource information has a hierarchical structure: individual tree attributes are summed at the plot level and then in turn, plot-level estimates are used to derive stand or large-area estimates of forest resources. Due to this hierarchy, it is imperative that individual tree attributes are measured with accuracy and precision. With the widespread use of different measurement tools, it is also important to understand the expected degree of precision associated with these measurements. The most prevalent tree attributes measured in the field are tree species, stem diameter-at-breast-height (dbh), and tree height. -

Tree Plantations As a Cost-Effective Tool for Reforestation of Abandoned Pastures in Amazonian Ecuador

Tree plantations as a cost-effective tool for reforestation of abandoned pastures in Amazonian Ecuador Pella Larsson Arbetsgruppen för Tropisk Ekologi Minor Field Study 95 Committee of Tropical Ecology Uppsala University, Sweden October 2003 Uppsala Tree plantations as a cost-effective tool for reforestation of abandoned pastures in Amazonian Ecuador Pella Larsson Masters degree thesis Department of Botany, Stockholm University S-106 91 Stockholm, 2003 Supervisors: Lenn Jerling and Ana Mariscal Chavez Abstract Tree plantations as a cost-effective tool for reforestation of abandoned pastures in Amazonian Ecuador Conversion to pastures is an important cause of deforestation of rainforests in South America. Cattle-grazing on previously forested land is unsustainable and leads to degradation through nutrient leakage, soil compaction, competition, changes in microclimate and lack of propagules. If the degradation is severe, succession may be arrested and the land remains open even if the grazing ceases. This study considers tree plantations as catalysts for reforestation, by breaking the barriers to succession and facilitating regeneration of native forest species in their understories. Woody regeneration in plantations was measured at Jatun Sacha biological field station in eastern Ecuador. Abundance and species richness of the regeneration in three different types of plantations were evaluated and compared to a control on abandoned pasture. Plantations dominated by two species of the genus Inga (I. ilta and I. edulis) were similar in the composition of their regeneration and had most species and individuals in the regeneration of the sampled plantation types. Plantations of mixed tree species had least abundant and species-rich regeneration, and the controls were in between. -

Wisconsin State Forests Continuous Forest Inventory

Wisconsin State Forests Continuous Forest Inventory VOLUME I: FIELD DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES FOR PHASE 2 PLOTS Version 4.0 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry October 2016 Wisconsin State Forests Continuous Forest Inventory Field Guide, Version 4.0 October 2016 Note to User: Wisconsin State Forests, Continuous Forest Inventory (WisCFI), Version 4.0 is adapted from the USDA Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Northern Region (NRS) field guide version 7.0.1 and NRS FIA version 7.0.1 is based on the National Core Field Guide, Version 7.0. All data elements are national unless indicated as follows: National data elements that end in “+N” (e.g., x.x+N) have had values, codes, or text added, changed, or adjusted from the CORE program. Any additional regional text for a national CORE data element is hi-lighted or shown as a “NRS Note.” All regional data elements end in “N” (e.g., x.xN). The text for a regional data element is not hi-lighted and does not have a corresponding variable in CORE. National CORE data elements or procedures with light gray text are not applicable in the North. NRS electronic file notes: o hyperlink cross-references are included for various sections, figures, and tables. National data elements that end in “+WisCFI” (e.g., x.x+WisCFI) have had values, codes, or text added, changed, or adjusted from the CORE program. Any additional WisCFI text for a national CORE data element is hi-lighted or shown as a “WisCFI Note.” All WisCFI-specific data elements end in “N-WisCFI” (e.g., x.xN-WisCFI). -

The Forestry Source

News for forest resource professionals published by the Society of American Foresters February 2019 • Vol. 24, No. 2 National Academies: Biotechnology Has Potential to Mitigate Forest Threats By Steve Wilent ccording to a report issued in Jan- uary by the National Academies of ASciences, Engineering, and Medi- cine, “Biotechnology has the potential to help mitigate threats to North American forests from insects and pathogens through the introduction of pest-resistant traits to forest trees.” The report, Forest Health and Biotechnology: Possibilities and Consider- ations, recommends research and invest- IN THIS ISSUE ment to assess and improve the utility of biotechnology—genetic engineering and Dead Wood Is Good Wood similar technologies—as a forest-health Gillian Martin, director of the Cavity Conser- tool (see tinyurl.com/ybor9ou4). vation Initiative, based in California’s Orange At the request of the US Department County, becomes animated when she talks of Agriculture (USDA), the US about dead wood in urban areas: “We have Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), lost an appreciation of the importance of dead and the US Endowment for Forestry and wood to wildlife, not only to cavity-nesting Communities, the National Academies birds but wildlife [in general]. In my presen- assembled a Committee on the Potential tations, I tell people, ‘Nature designed trees William A. Powell, a professor at SUNY ESF, has produced transgenic American chestnuts (Castanea den- to have two lives: one as a living healthy ma- for Biotechnology to Address Forest tata), called Darling 215 and 311, center, that are resistant to chestnut blight. Left: a blight-resistant Chinese ture tree and one when it starts to decline.’ Health to investigate the potential use of chestnut (C. -

Forest Inventory and Monitoring Guidelines A

FOREST INVENTORY AND MONITORING GUIDELINES A Guidebook for NCF Members Updated 2014 Prepared by Northwest Natural Resource Group & Stewardship Forestry Conservation Conservation is a state of harmony between men and land. By land is meant all of the things on, over, or in the earth. Harmony with land is like harmony with a friend; you cannot cherish his right hand and chop off his left. That is to say, you cannot love game and hate predators; you cannot conserve the waters and waste the ranges; you cannot build the forest and mine the farm. The land is one organism. Its parts, like our own parts, compete with each other and co-operate with each other. The competitions are as much a part of the inner workings as the co-operations. You can regulate them—cautiously—but not abolish them. The outstanding scientific discovery of the twentieth century is not television, or radio, but rather the complexity of the land organism. Only those who know the most about it can appreciate how little we know about it. The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: "What good is it?" If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering. -Aldo Leopold in Round River Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Forest Terminology for Multiple-Use Management1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. SS-FOR-11 Forest Terminology for Multiple-Use Management1 William Hubbard, Christopher Latt, Alan Long2 Like all specialized fields, forestry has gradually the myriad processes and organisms that shape a accumulated a large body of technical terms as well forest ecosystem. Most forestland owners highly as commonly used words given a new forestry twist. value a forest's non-timber values -- wildlife, Also, the increased emphasis on multiple-use recreation, scenic beauty, clean water. This glossary management and even newer management acknowledges and encourages a multiple-use philosophies has brought important new terms into perspective. the realm of forestry; words formerly used mainly by wildlife biologists, ecologists, environmental Many of the definitions in this glossary are based scientists, agroforesters, and other non-forestry on our own experiences in the field of forestry. Many experts. Such a wealth of terms invites confusion. others are based -- sometimes closely, sometimes This glossary is designed to cut through some of the loosely -- on definitions we have come across in confusion by providing, in one place, definitions for various Extension and non-Extension books and many of the terms commonly used in modern publications. Since our list of definitions was forestry. Traditional forestry terms still dominate, as assembled gradually over time, it is no longer one would expect of a forestry glossary, but the possible to say which definitions are based on printed addition of definitions from other fields sources and which are based on our own experiences accommodates today's multidisciplinary approach to and education. -

And Forestry Projects

2005 Public Disclosure Authorized SOURCEBOOK FOR LAND UsE, LAND-UsE Public Disclosure Authorized CHANGE AND FORESTRY PROJECTS Timothy Pearson, Sarah Walker and Sandra Brown Public Disclosure Authorized With input from Bernhard Schlamadinger (Joanneum Research), Igino Emmer (Face Public Disclosure Authorized Foundation), Wolfram Kägi (BSS) and Ian Noble, Benoit Bosquet and Lasse Ringius (World Bank) SOURCebOOK FOR LAND Use, LAND-Use CHANGE AND FOresTRY PROjeCTS Timothy Pearson, Sarah Walker and Sandra Brown With input from Bernhard Schlamadinger, Igino Emmer, Wolfram Kägi, Ian Noble, Benoit Bosquet and Lasse Ringius i SOURCE B OOK FOR LAND U S E , L AND-U S E CHANGE AND FORE S TRY PROJECT S SOURCE B OOK FOR LAND U S E , L AND-U S E CHANGE AND FORE S TRY PROJECT S i i CONTENT S 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE ......................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION TO THE KYOTO PROTOCOL AND THE CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM PROJECT CYCLE ........................................................................................... 2 2.1. The Clean Development Mechanism ...................................................................................... 2 3. INTRODUCTION TO THE BIOCARBON FUND AND THE BIOCARBON FUND CYCLE ...... 3 4. CONCEPTS OF ADDITIONALITY, BASELINE, LEAKAGE AND PERMANENCE .................... 4 4.1. Additionality ........................................................................................................................ 4 4.2. Baseline ..............................................................................................................................