Advances in Interventional Cardiology New Directions In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

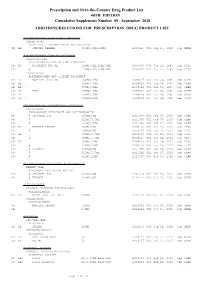

Additions and Deletions to the Drug Product List

Prescription and Over-the-Counter Drug Product List 40TH EDITION Cumulative Supplement Number 09 : September 2020 ADDITIONS/DELETIONS FOR PRESCRIPTION DRUG PRODUCT LIST ACETAMINOPHEN; BUTALBITAL; CAFFEINE TABLET;ORAL BUTALBITAL, ACETAMINOPHEN AND CAFFEINE >A> AA STRIDES PHARMA 325MG;50MG;40MG A 203647 001 Sep 21, 2020 Sep NEWA ACETAMINOPHEN; CODEINE PHOSPHATE SOLUTION;ORAL ACETAMINOPHEN AND CODEINE PHOSPHATE >D> AA WOCKHARDT BIO AG 120MG/5ML;12MG/5ML A 087006 001 Jul 22, 1981 Sep DISC >A> @ 120MG/5ML;12MG/5ML A 087006 001 Jul 22, 1981 Sep DISC TABLET;ORAL ACETAMINOPHEN AND CODEINE PHOSPHATE >A> AA NOSTRUM LABS INC 300MG;15MG A 088627 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >A> AA 300MG;30MG A 088628 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >A> AA ! 300MG;60MG A 088629 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA TEVA 300MG;15MG A 088627 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA 300MG;30MG A 088628 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA ! 300MG;60MG A 088629 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN ACETAMINOPHEN; HYDROCODONE BITARTRATE TABLET;ORAL HYDROCODONE BITARTRATE AND ACETAMINOPHEN >A> @ CEROVENE INC 325MG;5MG A 211690 001 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >A> @ 325MG;7.5MG A 211690 002 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >A> @ 325MG;10MG A 211690 003 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >D> AA VINTAGE PHARMS 300MG;5MG A 090415 001 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;5MG A 090415 001 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> AA 300MG;7.5MG A 090415 002 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;7.5MG A 090415 002 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> AA 300MG;10MG A 090415 003 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;10MG A 090415 003 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> @ XIROMED 325MG;5MG A 211690 -

Ticlopidine in Its Prodrug Form Is a Selective Inhibitor of Human Ntpdase1

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Mediators of Inflammation Volume 2014, Article ID 547480, 8 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/547480 Research Article Ticlopidine in Its Prodrug Form Is a Selective Inhibitor of Human NTPDase1 Joanna Lecka,1,2 Michel Fausther,1,2 Beat Künzli,3 and Jean Sévigny1,2 1 Departement´ de Microbiologie-Infectiologie et d’Immunologie, FacultedeM´ edecine,´ UniversiteLaval,Qu´ ebec,´ QC, Canada G1V 0A6 2 Centre de Recherche du CHU de Quebec,´ 2705 Boulevard Laurier, Local T1-49, Quebec,´ QC, Canada G1V 4G2 3 Department of Surgery, Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technische Universitat¨ Munchen,¨ 81675 Munich, Germany Correspondence should be addressed to Jean Sevigny;´ [email protected] Received 12 May 2014; Accepted 21 July 2014; Published 11 August 2014 Academic Editor: Mireia Mart´ın-Satue´ Copyright © 2014 Joanna Lecka et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (NTPDase1), like other ectonucleotidases, controls extracellular nucleotide levels and consequently their (patho)physiological responses such as in thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Selective NTPDase1 inhibitors would therefore be very useful. We previously observed that ticlopidine in its prodrug form, which does not affect P2 receptor activity, inhibited the recombinant form of human NTPDase1 ( =14M). Here we tested whether ticlopidine can be used as a selective inhibitor of NTPDase1. We confirmed that ticlopidine inhibits NTPDase1 in different forms and in different assays. The ADPase activity of intact HUVEC as well as of COS-7 cells transfected with human NTPDase1 was strongly inhibited by 100 M ticlopidine, 99 and 86%, respectively. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,498,481 B2 Rao Et Al

USOO9498481 B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,498,481 B2 Rao et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Nov. 22, 2016 (54) CYCLOPROPYL MODULATORS OF P2Y12 WO WO95/26325 10, 1995 RECEPTOR WO WO99/O5142 2, 1999 WO WOOO/34283 6, 2000 WO WO O1/92262 12/2001 (71) Applicant: Apharaceuticals. Inc., La WO WO O1/922.63 12/2001 olla, CA (US) WO WO 2011/O17108 2, 2011 (72) Inventors: Tadimeti Rao, San Diego, CA (US); Chengzhi Zhang, San Diego, CA (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS Drugs of the Future 32(10), 845-853 (2007).* (73) Assignee: Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., LaJolla, Tantry et al. in Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs (2007) 16(2):225-229.* CA (US) Wallentin et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine, 361 (11), 1045-1057 (2009).* (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Husted et al. in The European Heart Journal 27, 1038-1047 (2006).* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Auspex in www.businesswire.com/news/home/20081023005201/ U.S.C. 154(b) by Od en/Auspex-Pharmaceuticals-Announces-Positive-Results-Clinical M YW- (b) by ayS. Study (published: Oct. 23, 2008).* This patent is Subject to a terminal dis- Concert In www.concertpharma. com/news/ claimer ConcertPresentsPreclinicalResultsNAMS.htm (published: Sep. 25. 2008).* Concert2 in Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 6(6), 782 (2008).* (21) Appl. No.: 14/977,056 Springthorpe et al. in Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 17. 6013-6018 (2007).* (22) Filed: Dec. 21, 2015 Leis et al. in Current Organic Chemistry 2, 131-144 (1998).* Angiolillo et al., Pharmacology of emerging novel platelet inhibi (65) Prior Publication Data tors, American Heart Journal, 2008, 156(2) Supp. -

Cangrelor Ameliorates CLP-Induced Pulmonary Injury in Sepsis By

Luo et al. Eur J Med Res (2021) 26:70 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-021-00536-4 European Journal of Medical Research RESEARCH Open Access Cangrelor ameliorates CLP-induced pulmonary injury in sepsis by inhibiting GPR17 Qiancheng Luo1†, Rui Liu2†, Kaili Qu3, Guorong Liu1, Min Hang1, Guo Chen1, Lei Xu1, Qinqin Jin1 , Dongfeng Guo1* and Qi Kang1* Abstract Background: Sepsis is a common complication of severe wound injury and infection, with a very high mortality rate. The P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, cangrelor, is an antagonist anti-platelet drug. Methods: In our study, we investigated the protective mechanisms of cangrelor in CLP-induced pulmonary injury in sepsis, using C57BL/6 mouse models. Results: TdT-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) and Masson staining showed that apoptosis and fbrosis in lungs were alleviated by cangrelor treatment. Cangrelor signifcantly promoted surface expression of CD40L on platelets and inhibited CLP-induced neutrophils in Bronchoalveolar lavage fuid (BALF) (p < 0.001). We also found that cangrelor decreased the infammatory response in the CLP mouse model and inhibited the expression of infamma- tory cytokines, IL-1β (p < 0.01), IL-6 (p < 0.05), and TNF-α (p < 0.001). Western blotting and RT-PCR showed that cangre- lor inhibited the increased levels of G-protein-coupled receptor 17 (GPR17) induced by CLP (p < 0.001). Conclusion: Our study indicated that cangrelor repressed the levels of GPR17, followed by a decrease in the infam- matory response and a rise of neutrophils in BALF, potentially reversing CLP-mediated pulmonary injury during sepsis. Keywords: Sepsis, Infammation, Cangrelor, Platelet, GPR17 Background Te lung is one of the initial target organ of the systemic Sepsis is a serious disease and will lead a high mortal- infammatory response caused by sepsis, leading to alve- ity rate of approximately 22% in all over the world [1]. -

Prevention of Atherothrombotic Events in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: from Antithrombotic Therapies to New-Generation Glucose-Lowering Drugs

CONSENSUS STATEMENT EXPERT CONSENSUS DOCUMENT Prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with diabetes mellitus: from antithrombotic therapies to new-generation glucose-lowering drugs Giuseppe Patti1*, Ilaria Cavallari2, Felicita Andreotti3, Paolo Calabrò4, Plinio Cirillo5, Gentian Denas6, Mattia Galli3, Enrica Golia4, Ernesto Maddaloni 7, Rossella Marcucci8, Vito Maurizio Parato9,10, Vittorio Pengo6, Domenico Prisco8, Elisabetta Ricottini2, Giulia Renda11, Francesca Santilli12, Paola Simeone12 and Raffaele De Caterina11,13*, on behalf of the Working Group on Thrombosis of the Italian Society of Cardiology Abstract | Diabetes mellitus is an important risk factor for a first cardiovascular event and for worse outcomes after a cardiovascular event has occurred. This situation might be caused, at least in part, by the prothrombotic status observed in patients with diabetes. Therefore, contemporary antithrombotic strategies, including more potent agents or drug combinations, might provide greater clinical benefit in patients with diabetes than in those without diabetes. In this Consensus Statement, our Working Group explores the mechanisms of platelet and coagulation activity , the current debate on antiplatelet therapy in primary cardiovascular disease prevention, and the benefit of various antithrombotic approaches in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes. While acknowledging that current data are often derived from underpowered, observational studies or subgroup analyses of larger trials, we propose -

Kengrexal, INN-Cangrelor Tetrasodium

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Kengrexal 50 mg powder for concentrate for solution for injection/infusion 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each vial contains cangrelor tetrasodium corresponding to 50 mg cangrelor. After reconstitution 1 mL of concentrate contains 10 mg cangrelor. After dilution 1 mL of solution contains 200 micrograms cangrelor. Excipient with known effect Each vial contains 52.2 mg sorbitol. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Powder for concentrate for solution for injection/infusion. White to off-white lyophilised powder. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Kengrexal, co-administered with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is indicated for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events in adult patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) who have not received an oral P2Y12 inhibitor prior to the PCI procedure and in whom oral therapy with P2Y12 inhibitors is not feasible or desirable. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Kengrexal should be administered by a physician experienced in either acute coronary care or in coronary intervention procedures and is intended for specialised use in an acute and hospital setting. Posology The recommended dose of Kengrexal for patients undergoing PCI is a 30 micrograms/kg intravenous bolus followed immediately by 4 micrograms/kg/min intravenous infusion. The bolus and infusion should be initiated prior to the procedure and continued for at least two hours or for the duration of the procedure, whichever is longer. At the discretion of the physician, the infusion may be continued for a total duration of four hours, see section 5.1. -

Xử Trí Quá Liều Thuốc Chống Đông

XỬ TRÍ QUÁ LIỀU THUỐC CHỐNG ĐÔNG TS. Trần thị Kiều My Bộ môn Huyết học Đại học Y Hà nội Khoa Huyết học Bệnh viện Bạch mai TS. Trần thị Kiều My Coagulation cascade TIÊU SỢI HUYẾT THUỐC CHỐNG ĐÔNG VÀ CHỐNG HUYẾT KHỐI • Thuốc chống ngưng tập tiểu cầu • Thuốc chống các yếu tố đông máu huyết tương • Thuốc tiêu sợi huyết và huyết khối Thuốc chống ngưng tập tiểu cầu Đường sử Xét nghiệm theo dõi dụng Nhóm thuốc ức chế Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa: TM VerifyNow Abciximab, ROTEM Tirofiban SLTC, Hb, Hct, APTT, Clotting time Eptifibatide, ACT, aPTT, TT, and PT Nhóm ức chế receptor ADP /P2Y12 Uống NTTC, phân tích chức +thienopyridines năng TC bằng PFA, Clopidogrel ROTEM Prasugrel VerifyNow Ticlopidine +nucleotide/nucleoside analogs Cangrelor Elinogrel, TM Ticagrelor TM+uống ƯC ADP Uống Nhóm Prostaglandin analogue (PGI2): Uống NTTC, phân tích chức Beraprost, năng TC bằng PFA, ROTEM Iloprost (Illomedin), Xịt hoặc truyền VerifyNow TM Prostacyclin,Treprostinil Nhóm ức chế COX: Uống NTTC, phân tích Acetylsalicylicacid/Aspirin#Aloxiprin,Carbasalate, chức năng TC bằng calcium, Indobufen, Triflusal PFA, ROTEM VerifyNow Nhóm ức chế Thromboxane: Uống NTTC, phân tích chức +thromboxane synthase inhibitors năng TC bằng PFA, Dipyridamole (+Aspirin), Picotamide ROTEM +receptor antagonist : Terutroban† VerifyNow Nhóm ức chế Phosphodiesterase: Uống NTTC, phân tích chức Cilostazol, Dipyridamole, Triflusal năng TC bằng PFA, ROTEM VerifyNow Nhóm khác: Uống NTTC, phân tích chức Cloricromen, Ditazole, Vorapaxar năng TC bằng PFA, ROTEM VerifyNow Dược động học một số thuốc -

P2 Receptors in Cardiovascular Regulation and Disease

Purinergic Signalling (2008) 4:1–20 DOI 10.1007/s11302-007-9078-7 REVIEW P2 receptors in cardiovascular regulation and disease David Erlinge & Geoffrey Burnstock Received: 3 May 2007 /Accepted: 22 August 2007 /Published online: 21 September 2007 # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The role of ATP as an extracellular signalling Introduction molecule is now well established and evidence is accumulating that ATP and other nucleotides (ADP, UTP and UDP) play Ever since the first proposition of cell surface receptors for important roles in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysi- nucleotides [1, 2], it has become increasingly clear that, in ology, acting via P2X (ion channel) and P2Y (G protein- addition to functioning as an intracellular energy source, the coupled) receptors. In this article we consider the dual role of purines and pyrimidines ATP, adenosine diphosphate ATP in regulation of vascular tone, released as a cotransmitter (ADP), uridine triphosphate (UTP) and uridine diphosphate from sympathetic nerves or released in the vascular lumen in (UDP) can serve as important extracellular signalling response to changes in blood flow and hypoxia. Further, molecules [3, 4] acting on 13 P2X homo- and heteromul- purinergic long-term trophic and inflammatory signalling is timer ionotropic and 8 P2Y metabotropic receptor subtypes described in cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and [5, 6] (Table 1). To terminate signalling, ectonucleotidases death in angiogenesis, vascular remodelling, restenosis and are present in the circulation and on cell surfaces, rapidly atherosclerosis. The effects on haemostasis and cardiac degrading extracellular ATP into ADP, AMP and adenosine regulation is reviewed. The involvement of ATP in vascular [7, 8]. -

Prasugrel Mylan 10 Mg Film-Coated Tablets Prasugrel

Package leaflet: Information for the user Prasugrel Mylan 5 mg film-coated tablets Prasugrel Mylan 10 mg film-coated tablets prasugrel Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. – Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. – If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. – This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. – If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Prasugrel Mylan is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you take Prasugrel Mylan 3. How to take Prasugrel Mylan 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Prasugrel Mylan 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Prasugrel Mylan is and what it is used for Prasugrel Mylan, which contains the active substance prasugrel, belongs to a group of medicines called antiplatelet agents. Platelets are very small cell particles that circulate in the blood. When a blood vessel is damaged, for example if it is cut, platelets clump together to help form a blood clot (thrombus). Therefore, platelets are essential to help stop bleeding. If clots form within a hardened blood vessel such as an artery they can be very dangerous as they can cut off the blood supply, causing a heart attack (myocardial infarction), stroke or death. -

Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play

The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Executive Agency for Health and Consumers Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play 24 January 2012 Final Report Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Acknowledgements Matrix Insight Ltd would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this research. We are especially grateful to the following institutions for their support throughout the study: the Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU) including their national member associations in Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland and the United Kingdom; the European Medical Association (EMANET); the Observatoire Social Européen (OSE); and The Netherlands Institute for Health Service Research (NIVEL). For questions about the report, please contact Dr Gabriele Birnberg ([email protected] ). Matrix Insight | 24 January 2012 2 Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Executive Summary This study has been carried out in the context of Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients’ rights in cross- border healthcare (CBHC). The CBHC Directive stipulates that the European Commission shall adopt measures to facilitate the recognition of prescriptions issued in another Member State (Article 11). At the time of submission of this report, the European Commission was preparing an impact assessment with regards to these measures, designed to help implement Article 11. -

A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, Pka, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, pKa, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs Milan Remko 1,*, Anna Remková 2 and Ria Broer 3 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Comenius University in Bratislava, Odbojarov 10, SK-832 32 Bratislava, Slovakia 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Slovak Medical University, Limbová 12, SK–833 03 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 3 Department of Theoretical Chemistry, Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, 9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-2-5011-7291 Academic Editor: Michael Henein Received: 18 February 2016; Accepted: 11 March 2016; Published: 19 March 2016 Abstract: Theoretical chemistry methods have been used to study the molecular properties of antiplatelet agents (ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel, elinogrel, ticagrelor and cangrelor) and several thiol-containing active metabolites. The geometries and energies of most stable conformers of these drugs have been computed at the Becke3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of density functional theory. Computed dissociation constants show that the active metabolites of prodrugs (ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel) and drugs elinogrel and cangrelor are completely ionized at pH 7.4. Both ticagrelor and its active metabolite are present at pH = 7.4 in neutral undissociated form. The thienopyridine prodrugs ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel are lipophilic and insoluble in water. Their lipophilicity is very high (about 2.5–3.5 logP values). The polar surface area, with regard to the structurally-heterogeneous character of these antiplatelet drugs, is from very large interval of values of 3–255 Å2. -

Cilostazol Protects Rats Against Alcohol‑Induced Hepatic Fibrosis Via Suppression of TGF‑Β1/CTGF Activation and the Camp/Epac1 Pathway

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 17: 2381-2388, 2019 Cilostazol protects rats against alcohol‑induced hepatic fibrosis via suppression of TGF‑β1/CTGF activation and the cAMP/Epac1 pathway KUN HAN, YANTING ZHANG and ZHENWEI YANG Department of Gastroenterology, Xi'an Central Hospital, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710003, P.R. China Received July 2, 2018; Accepted November 23, 2018 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2019.7207 Abstract. Alcohol abuse and chronic alcohol consump- Introduction tion are major causes of alcoholic liver disease worldwide, particularly alcohol‑induced hepatic fibrosis (AHF). Liver Liver fibrosis is a wound‑healing response to a variety of liver fibrosis is an important public health concern because of its insults, including excessive alcohol intake. Alcohol abuse and high morbidity and mortality. The present study examined chronic alcohol consumption are major causes of alcoholic the mechanisms and effects of the phosphodiesterase III liver disease (ALD) worldwide (1). Alcohol‑induced hepatic inhibitor cilostazol on AHF. Rats received alcohol infu- fibrosis (AHF) may cause serious hepatic cirrhosis, and is sions via gavage to induce liver fibrosis and were treated widely accepted as a milestone event in ALD (2). However, with colchicine (positive control) or cilostazol. The serum recent evidence indicates that liver fibrosis is reversible and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and acetaldehyde dehydro- that the liver may recover from cirrhosis (3). Therefore, eluci- genase (ALDH) activities and the albumin/globulin (A/G), dation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms is urgently enzymes and hyaluronic acid (HA), type III precollagen required to prevent AHF. (PC III), laminin (LA), and type IV collagen (IV‑C) levels The exact mechanism remains unclear, but certain changes were measured using commercially available kits.