Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ambell-5 Amlodipine Besylate Tablets Usp 5 Mg

AMBELL-5 AMLODIPINE BESYLATE TABLETS USP 5 MG 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT AMBELL-5 Amlodipine Besylate Tablets USP 5 mg 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each uncoated tablet contains: Amlodipine Besilate USP Eq. to Amlodipine………….5 mg Excipients…………………..q.s. For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Uncoated Tablets 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications - Hypertension - Chronic stable and vasospastic anginal pectoris - Vasospastic (Prinzmetal's) angina 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology Adults For both hypertension and angina the usual initial dose is 5 mg Amlodipine once daily which may be increased to a maximum dose of 10 mg depending on the individual patient's response. In hypertensive patients, amlodipine has been used in combination with a thiazide diuretic, alpha blocker, beta blocker, or an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. For angina, amlodipine may be used as monotherapy or in combination with other antianginal medicinal products in patients with angina that is refractory to nitrates and/or to adequate doses of beta blockers. No dose adjustment of amlodipine is required upon concomitant administration of thiazide diuretics, beta blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Special populations Elderly Amlodipine used at similar doses in elderly or younger patients is equally well tolerated. Normal dosage regimens are recommended in the elderly, but increase of the dosage should take place with care (see sections 4.4 and 5.2). Patients with hepatic impairment Dosage recommendations have not been established in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment, therefore dose selection should be cautious and should start at the lower end of the dosing range (see sections 4.4 and 5.2). -

Characterising the Risk of Major Bleeding in Patients With

EU PE&PV Research Network under the Framework Service Contract (nr. EMA/2015/27/PH) Study Protocol Characterising the risk of major bleeding in patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: non-interventional study of patients taking Direct Oral Anticoagulants in the EU Version 3.0 1 June 2018 EU PAS Register No: 16014 EMA/2015/27/PH EUPAS16014 Version 3.0 1 June 2018 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Title ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Marketing authorization holder ................................................................................................. 5 3 Responsible parties ................................................................................................................... 5 4 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 6 5 Amendments and updates ......................................................................................................... 7 6 Milestones ................................................................................................................................. 8 7 Rationale and background ......................................................................................................... 9 8 Research question and objectives .............................................................................................. 9 9 Research methods .................................................................................................................... -

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

Interactions Medicamenteuses Index Des Classes Pharmaco

INTERACTIONS MEDICAMENTEUSES INDEX DES CLASSES PHARMACO-THERAPEUTIQUES Mise à jour avril 2006 acides biliaires (acide chenodesoxycholique, acide ursodesoxycholique) acidifiants urinaires adrénaline (voie bucco-dentaire ou sous-cutanée) (adrenaline alcalinisants urinaires (acetazolamide, sodium (bicarbonate de), trometamol) alcaloïdes de l'ergot de seigle dopaminergiques (bromocriptine, cabergoline, lisuride, pergolide) alcaloïdes de l'ergot de seigle vasoconstricteurs (dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, methylergometrine) alginates (acide alginique, sodium et de trolamine (alginate de)) alphabloquants à visée urologique (alfuzosine, doxazosine, prazosine, tamsulosine, terazosine) amidons et gélatines (gelatine, hydroxyethylamidon, polygeline) aminosides (amikacine, dibekacine, gentamicine, isepamicine, kanamycine, netilmicine, streptomycine, tobramycine) amprénavir (et, par extrapolation, fosamprénavir) (amprenavir, fosamprenavir) analgésiques morphiniques agonistes (alfentanil, codeine, dextromoramide, dextropropoxyphene, dihydrocodeine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, pethidine, phenoperidine, remifentanil, sufentanil, tramadol) analgésiques morphiniques de palier II (codeine, dextropropoxyphene, dihydrocodeine, tramadol) analgésiques morphiniques de palier III (alfentanil, dextromoramide, fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, pethidine, phenoperidine, remifentanil, sufentanil) analogues de la somatostatine (lanreotide, octreotide) androgènes (danazol, norethandrolone, testosterone) anesthésiques volatils halogénés -

List of Union Reference Dates A

Active substance name (INN) EU DLP BfArM / BAH DLP yearly PSUR 6-month-PSUR yearly PSUR bis DLP (List of Union PSUR Submission Reference Dates and Frequency (List of Union Frequency of Reference Dates and submission of Periodic Frequency of submission of Safety Update Reports, Periodic Safety Update 30 Nov. 2012) Reports, 30 Nov. -

Summary of Product Characteristics

Health Products Regulatory Authority Summary of Product Characteristics 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Salbutamol CFC-Free Inhaler 100 micrograms per metered dose, pressurised inhalation, suspension 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION One metered dose contains 100 micrograms of salbutamol (equivalent to 120 micrograms of salbutamol sulphate). This is equivalent to a delivered dose of 90 micrograms of salbutamol (equivalent to 108 micrograms of salbutamol sulphate). For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Pressurised inhalation suspension Pressurised inhalation suspension supplied in an aluminium canister with a metering valve and a plastic actuator and dust cap. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic Indications Salbutamol CFC-Free Inhaler is indicated in adults, adolescents and children. For babies and children under 4 years of age, see sections 4.2 and 5.1. Salbutamol CFC-Free Inhaler is indicated for the relief and prevention of bronchial asthma and conditions associated with reversible airways obstruction. Salbutamol CFC-Free Inhaler can be used as relief medication in the management of mild, moderate or severe asthma, provided that its use does not delay the introduction and use of regular inhaled corticosteroid therapy, where necessary. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Salbutamol CFC-Free Inhaler is for oral inhalation use only. Posology Adults (including the elderly) and adolescents (children 12 years and over): For the relief of acute bronchospasm, one inhalation (100 micrograms) increasing to two inhalations (200 micrograms), if necessary. To prevent allergen- or exercise-induced symptoms, two inhalations (200 micrograms) should be taken 10-15 minutes before challenge. Maximum daily dose: two inhalations (200 micrograms) up to four times a day. -

Comprehensive Screening of Diuretics in Human Urine Using Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry

id5246609 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com AAnnaallyyttiiccaaISllS N : 0974-7419 Volume 13 Issue 7 CCHHEEAnMM IndIIiSaSnT TJoRuRrnYaYl Full Paper ACAIJ, 13(7) 2013 [270-283] Comprehensive screening of diuretics in human urine using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry Shobha Ahi1, Alka Beotra1*, G.B.K.S.Prasad2 1National Dope Testing Laboratory, Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi,-110003, (INDIA) 2SOS in Biochemistry, Jiwaji University, Gwalior, (INDIA) E-mail : [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Diuretics are drugs that increase the rate of urine flow and sodium excretion Doping, diuretics; to adjust the volume and composition of body fluids. There are several LC-MS/MS; WADA; major categories of this drug class and the compounds vary greatly in Drugs of abuse. structure, physicochemical properties, effects on urinary composition and renal haemodynamics, and site mechanism of action. Diuretics are often abused by athletes to excrete water for rapid weight loss and to mask the presence of other banned substances. Because of their abuse by athletes, ’s (WADA) diuretics have been included in the World Anti-Doping Agency list of prohibited substances. The diuretics are routinely screened by anti- doping laboratories as the use of diuretics is banned both in-competition and out-of-competition. This work provides an improved, fast and selective –tandem mass spectrometric (LC/MS/MS) method liquid chromatography for the screening of 22 diuretics and probenecid in human urine. The samples preparation was performed by liquid-liquid extraction. The limit of detection (LOD) for all substances was between 10-20 ng/ml or better. -

Cilostazol Protects Rats Against Alcohol‑Induced Hepatic Fibrosis Via Suppression of TGF‑Β1/CTGF Activation and the Camp/Epac1 Pathway

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 17: 2381-2388, 2019 Cilostazol protects rats against alcohol‑induced hepatic fibrosis via suppression of TGF‑β1/CTGF activation and the cAMP/Epac1 pathway KUN HAN, YANTING ZHANG and ZHENWEI YANG Department of Gastroenterology, Xi'an Central Hospital, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710003, P.R. China Received July 2, 2018; Accepted November 23, 2018 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2019.7207 Abstract. Alcohol abuse and chronic alcohol consump- Introduction tion are major causes of alcoholic liver disease worldwide, particularly alcohol‑induced hepatic fibrosis (AHF). Liver Liver fibrosis is a wound‑healing response to a variety of liver fibrosis is an important public health concern because of its insults, including excessive alcohol intake. Alcohol abuse and high morbidity and mortality. The present study examined chronic alcohol consumption are major causes of alcoholic the mechanisms and effects of the phosphodiesterase III liver disease (ALD) worldwide (1). Alcohol‑induced hepatic inhibitor cilostazol on AHF. Rats received alcohol infu- fibrosis (AHF) may cause serious hepatic cirrhosis, and is sions via gavage to induce liver fibrosis and were treated widely accepted as a milestone event in ALD (2). However, with colchicine (positive control) or cilostazol. The serum recent evidence indicates that liver fibrosis is reversible and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and acetaldehyde dehydro- that the liver may recover from cirrhosis (3). Therefore, eluci- genase (ALDH) activities and the albumin/globulin (A/G), dation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms is urgently enzymes and hyaluronic acid (HA), type III precollagen required to prevent AHF. (PC III), laminin (LA), and type IV collagen (IV‑C) levels The exact mechanism remains unclear, but certain changes were measured using commercially available kits. -

Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis Stability Of

Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 49 (2009) 519–524 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpba Short communication Stability of selected chlorinated thiazide diuretics K. Deventer a,∗, G. Baele b, P. Van Eenoo a, O.J. Pozo a, F.T. Delbeke a a DoCoLab, UGent, Department of Clinical Chemistry, Microbiology and Immunology, Technologiepark 30, B-9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium b Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, Krijgslaan 281, S9, B-9000 Gent, Belgium article info abstract Article history: In sports, diuretics are used for two main reasons: to flush previously taken prohibited substances with Received 6 August 2008 forced diuresis and in sports where weight classes are involved to achieve acute weight loss. A com- Received in revised form 5 November 2008 mon property observed for thiazides is hydrolysis in aqueous media resulting in the formation of the Accepted 6 November 2008 degradation product aminobenzenedisulphonamide. This degradation product can be observed for sev- Available online 13 November 2008 eral thiazides. Because there is limited information regarding the effect of pH, temperature and light on the stability of thiazides, these parameters were investigated for chlorothiaizide, hydrochlorothiazide Keywords: and altizide. For all three compounds the degradation product could be detected after incubation at pH Doping ◦ Urine 9.5 for 48 h at 60 C. At lower pH and temperature the degradation product could not be detected for all Diuretics compounds. When samples were exposed to UV-light altizide and hydrochlorothiazide were photode- Thiazides graded to chlorothiazide. When the degradation rate between the different compounds was compared Sports for a given temperature and pH, altizide is the most unstable compound. -

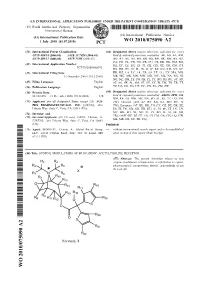

Wo 2010/075090 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 1 July 2010 (01.07.2010) WO 2010/075090 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C07D 409/14 (2006.01) A61K 31/7028 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, C07D 409/12 (2006.01) A61P 11/06 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US2009/068073 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 15 December 2009 (15.12.2009) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (25) Filing Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, (26) Publication Language: English TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/122,478 15 December 2008 (15.12.2008) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): AUS- ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, PEX PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

Marie Louise De Bruin Drug Induced Arrhythmias

Marie Louise De Bruin drug induced arrhythmias Quantifying the problem Cover design: Tom Frantzen CIP-gegevens Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag De Bruin, Marie Louise Drug-induced arrhythmias, quantifying the problem / Marie Louise De Bruin Thesis Utrecht - with ref.- with summary in Dutch ISBN: 90-808203-3-4 © Marie Louise De Bruin drug-induced arrhythmias, quantifying the problem Geneesmiddel-geïnduceerde hartritmestoornissen, kwantificering van het probleem (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. dr W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 1 december 2004 des namiddags om 14.30 uur door Marie Louise De Bruin Geboren op 1 april 1974 te Haarlem promotores Prof. dr H.G.M. Leufkens Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (UIPS), Department of Pharmaco- epidemiology and Pharmacotherapy, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands Prof. dr A.W. Hoes Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands The work in this thesis was performed at the Department of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacotherapy of the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (Utrecht) and the Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care (Utrecht), in collabo- ration with the PHARMO Institute (Utrecht), the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb (‘s-Hertogenbosch), the WHO-Uppsala Monitoring Centre (Uppsala, Sweden) and the Academic Medical Center (Amsterdam). The research presented in this thesis was funded by the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, and an unrestricted grant from the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board. The study presented in chapter 3.1 was funded by an unrestricted grant from Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium.