Health and Social Outcomes Associated with High-Risk Alcohol Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Additions and Deletions to the Drug Product List

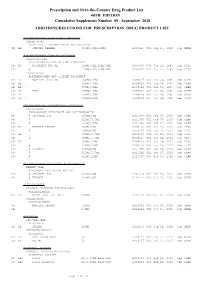

Prescription and Over-the-Counter Drug Product List 40TH EDITION Cumulative Supplement Number 09 : September 2020 ADDITIONS/DELETIONS FOR PRESCRIPTION DRUG PRODUCT LIST ACETAMINOPHEN; BUTALBITAL; CAFFEINE TABLET;ORAL BUTALBITAL, ACETAMINOPHEN AND CAFFEINE >A> AA STRIDES PHARMA 325MG;50MG;40MG A 203647 001 Sep 21, 2020 Sep NEWA ACETAMINOPHEN; CODEINE PHOSPHATE SOLUTION;ORAL ACETAMINOPHEN AND CODEINE PHOSPHATE >D> AA WOCKHARDT BIO AG 120MG/5ML;12MG/5ML A 087006 001 Jul 22, 1981 Sep DISC >A> @ 120MG/5ML;12MG/5ML A 087006 001 Jul 22, 1981 Sep DISC TABLET;ORAL ACETAMINOPHEN AND CODEINE PHOSPHATE >A> AA NOSTRUM LABS INC 300MG;15MG A 088627 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >A> AA 300MG;30MG A 088628 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >A> AA ! 300MG;60MG A 088629 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA TEVA 300MG;15MG A 088627 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA 300MG;30MG A 088628 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN >D> AA ! 300MG;60MG A 088629 001 Mar 06, 1985 Sep CAHN ACETAMINOPHEN; HYDROCODONE BITARTRATE TABLET;ORAL HYDROCODONE BITARTRATE AND ACETAMINOPHEN >A> @ CEROVENE INC 325MG;5MG A 211690 001 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >A> @ 325MG;7.5MG A 211690 002 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >A> @ 325MG;10MG A 211690 003 Feb 07, 2020 Sep CAHN >D> AA VINTAGE PHARMS 300MG;5MG A 090415 001 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;5MG A 090415 001 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> AA 300MG;7.5MG A 090415 002 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;7.5MG A 090415 002 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> AA 300MG;10MG A 090415 003 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >A> @ 300MG;10MG A 090415 003 Jan 24, 2011 Sep DISC >D> @ XIROMED 325MG;5MG A 211690 -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Pharmacol Ther

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Pharmacol Ther. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 August 1. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Pharmacol Ther. 2009 August ; 123(2): 239±254. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.04.002. Ethnobotany as a Pharmacological Research Tool and Recent Developments in CNS-active Natural Products from Ethnobotanical Sources Will C. McClatcheya,*, Gail B. Mahadyb, Bradley C. Bennettc, Laura Shielsa, and Valentina Savod a Department of Botany, University of Hawaìi at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, U.S.A b Department of Pharmacy Practice, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60612, U.S.A c Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, U.S.A d Dipartimento di Biologia dì Roma Trè, Viale Marconi, 446, 00146, Rome, Italy Abstract The science of ethnobotany is reviewed in light of its multidisciplinary contributions to natural product research for the development of pharmaceuticals and pharmacological tools. Some of the issues reviewed involve ethical and cultural perspectives of healthcare and medicinal plants. While these are not usually part of the discussion of pharmacology, cultural concerns potentially provide both challenges and insight for field and laboratory researchers. Plant evolutionary issues are also considered as they relate to development of plant chemistry and accessing this through ethnobotanical methods. The discussion includes presentation of a range of CNS-active medicinal plants that have been recently examined in the field, laboratory and/or clinic. Each of these plants is used to illustrate one or more aspects about the valuable roles of ethnobotany in pharmacological research. -

A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, Pka, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, pKa, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs Milan Remko 1,*, Anna Remková 2 and Ria Broer 3 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Comenius University in Bratislava, Odbojarov 10, SK-832 32 Bratislava, Slovakia 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Slovak Medical University, Limbová 12, SK–833 03 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 3 Department of Theoretical Chemistry, Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, 9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-2-5011-7291 Academic Editor: Michael Henein Received: 18 February 2016; Accepted: 11 March 2016; Published: 19 March 2016 Abstract: Theoretical chemistry methods have been used to study the molecular properties of antiplatelet agents (ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel, elinogrel, ticagrelor and cangrelor) and several thiol-containing active metabolites. The geometries and energies of most stable conformers of these drugs have been computed at the Becke3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of density functional theory. Computed dissociation constants show that the active metabolites of prodrugs (ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel) and drugs elinogrel and cangrelor are completely ionized at pH 7.4. Both ticagrelor and its active metabolite are present at pH = 7.4 in neutral undissociated form. The thienopyridine prodrugs ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel are lipophilic and insoluble in water. Their lipophilicity is very high (about 2.5–3.5 logP values). The polar surface area, with regard to the structurally-heterogeneous character of these antiplatelet drugs, is from very large interval of values of 3–255 Å2. -

Quality Use of Medicines in Residential Aged Care

RESEARCH Quality use of medicines in Michael Somers residential aged care Ella Rose Dasha Simmonds Claire Whitelaw Janine Calver Christopher Beer Background Approximately 190 000 people in high risk of ADEs in frail older people. For example, Older people are more likely to be Australia were estimated to have anticholinergic drugs commonly produce adverse exposed to polypharmacy. People dementia in 2006, with the prevalence effects in elderly people and are more likely to be with dementia, especially those living expected to increase to 465 000 by 2031.1 prescribed to people with dementia than those in residential aged care facilities The prevalence of dementia increases without.7 (RACFs), are at particularly high risk of with age, from 6.5% of Australians aged Antipsychotic medications are commonly used medication harm. We sought to describe medications prescribed for a sample of 65 years and over to 22% of Australians to manage the behavioural and psychological 2 people with dementia living in RACFs. aged 85 years and over. Dementia is symptoms of dementia (BPSD), such as associated with a large burden of disease psychosis, depression, agitation, aggression Methods in Australia’s aging population, costing and disinhibition.1,8 There is concern that A total of 351 residents with dementia Australia $1.4 billion in 2003.2 Most of this antipsychotics are used too frequently as a aged over 65 years were recruited from 36 RACFs in Western Australia. burden was associated with residential first line treatment for BPSD, with the risks of 2 Data on all medications prescribed aged care facilities (RACFs). Dementia antipsychotic use outweighing the benefits at their were collected, including conventional is the medical problem most frequently likely level of use.8 For example, risperidone, an medications, herbal medications, managed by general practitioners atypical antipsychotic prescribed frequently for the vitamins and minerals. -

The Delivery Strategy of Paclitaxel Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Coated with Platelet Membrane

cancers Article The Delivery Strategy of Paclitaxel Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Coated with Platelet Membrane 1, 1, 1 2 3 Ki-Hyun Bang y, Young-Guk Na y , Hyun Wook Huh , Sung-Joo Hwang , Min-Soo Kim , Minki Kim 1, Hong-Ki Lee 1,* and Cheong-Weon Cho 1,* 1 College of Pharmacy, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134, Korea; [email protected] (K.-H.B.); [email protected] (Y.-G.N.); [email protected] (H.W.H.); [email protected] (M.K.) 2 College of Pharmacy and Yonsei Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Yonsei University, 162-1 Songdo-dong, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon 406-840, Korea; [email protected] 3 College of Pharmacy, Pusan National University, 63 Busandaehak-ro, Geumjeong-gu, Busan 609-735, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.-K.L.); [email protected] (C.-W.C.); Tel.: +82-42-821-5934 (H.-K.L. & C.-W.C.); Fax: +82-42-823-6566 (H.-K.L. & C.-W.C.) These authors contributed equally. y Received: 2 May 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 11 June 2019 Abstract: Strategies for the development of anticancer drug delivery systems have undergone a dramatic transformation in the last few decades. Lipid-based drug delivery systems, such as a nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC), are one of the systems emerging to improve the outcomes of tumor treatments. However, NLC can act as an intruder and cause an immune response. To overcome this limitation, biomimicry technology was introduced to decorate the surface of the nanoparticles with various cell membrane proteins. Here, we designed paclitaxel (PT)-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (PT-NLC) with platelet (PLT) membrane protein because PLT is involved with angiogenesis and interaction of circulating tumor cells. -

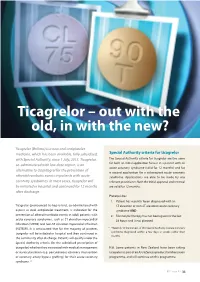

Ticagrelor – out with the Old, in with the New?

Ticagrelor – out with the old, in with the new? Ticagrelor (Brilinta) is a new oral antiplatelet medicine, which has been available, fully subsidised, Special Authority criteria for ticagrelor with Special Authority, since 1 July, 2013. Ticagrelor, The Special Authority criteria for ticagrelor are the same co-administered with low dose aspirin, is an for both an initial application for use in a patient with an acute coronary syndrome (valid for 12 months) and for alternative to clopidogrel for the prevention of a second application for a subsequent acute coronary atherothrombotic events in patients with acute syndrome. Applications are able to be made by any coronary syndromes. In most cases, ticagrelor will relevant practitioner. Both the initial approval and renewal be initiated in hospital and continued for 12 months are valid for 12 months. after discharge. Prerequisites: 1. Patient has recently* been diagnosed with an Ticagrelor (pronounced tie-kag-re-lore), co-administered with ST elevation or non-ST elevation acute coronary aspirin as dual antiplatelet treatment, is indicated for the syndrome AND prevention of atherothrombotic events in adult patients with 2. Fibrinolytic therapy has not been given in the last acute coronary syndromes, such as ST elevation myocardial 24 hours and is not planned infarction (STEMI) and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). It is anticipated that for the majority of patients, * “Recently” in the context of this Special Authority is acute coronary ticagrelor will be initiated in hospital and then continued in syndrome diagnosed within a few days or weeks rather than months. the community after discharge. Patients will qualify under the Special Authority criteria (for the subsidised prescription of ticagrelor) whether they are treated with medical management N.B. -

PHRP March 2015

March 2015; Vol. 25(2):e2521518 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17061/phrp2521518 www.phrp.com.au Research Manual versus automated coding of free-text self-reported medication data in the 45 and Up Study: a validation study Danijela Gnjidica,b,i, Sallie-Anne Pearsona,c, Sarah N Hilmerb,d, Jim Basilakise, Andrea L Schaffera, Fiona M Blythb,f,g and Emily Banksg,h, on behalf of the High Risk Prescribing Investigators a Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia b Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia c Sydney School of Public Health, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia d Royal North Shore Hospital and Kolling Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia e School of Computing, Engineering and Mathematics, University of Western Sydney, NSW, Australia f Centre for Education and Research on Ageing (CERA), Concord Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia g The Sax Institute, Sydney, NSW, Australia h National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT i Corresponding author: [email protected] Article history Abstract Publication date: March 2015 Background: Increasingly, automated methods are being used to code free- Citation: Gnjidic D, Pearson S, Hilmer S, text medication data, but evidence on the validity of these methods is limited. Basilakis J, Schaffer AL, Blyth FM, Banks E. To examine the accuracy of automated coding of previously keyed Manual versus automated coding of free-text Aim: in free-text medication data compared with manual coding of original self-reported medication data in the 45 and Up Study: a validation study. Public Health handwritten free-text responses (the ‘gold standard’). -

Plant Powers, Poisons, and Herb Craft

PLANT POWERS, POISONS, AND HERB CRAFT BY DALE PENDELL Foreword by Gary Snyde, $21.95 US In 'Pharmako/Poeia, Dale Pendell offers a mesmerizing guide to psychoactive Alternative plants, from their pharmacological roots to the literary offshoots. "This is a Health/ book," writes Gary Snyder, "about danger: dangerous knowledge, even more Literature dangerous ignorance." Against the greater danger, ignorance, Pendell strikes a formidable blow, as he proves himself a wise and witty guide to our plant teach- ers, their powers and their poisons. "Dale Pendell reactivates the ancient connection between the bardic poet and the shaman. His Pharmako/Poeia is a litany to the secret plant allies that have always accompanied us along the alchemical trajectory that leads to a new and yet authentically archaic future." — Terence McKenna, author of True Hallucinations "Much of our life-force calls upon the plant world for support, in medicines and in foods, as both allies and teachers. Pendell provides a beautifully crafted bridge between these two worlds. The magic he shares is that the voices are spoken and heard both ways; we communicate with plants and they with us. This book is a moving and poetic presentation of this dialogue." — Dr. Alexander T. Shulgin, University of California at Berkeley, Department of Public Health "Pharmako/Poeia is an epic poem on plant humours, an abstruse alchemic treatise, an experiential narrative jigsaw puzzle, a hip and learned wild-nature reference text, a comic paean to cosmic consciousness, an ecological handbook, a dried-herb pastiche, a countercultural encyclopedia of ancient fact and lore that cuts through the present 'conservative' war-on-drugs psychobabble." - Allen Ginsberg, poet Cover design "Dale PendelFs remarkable book will make it impossible to and color work ever again underestimate the most unprepossessing plant. -

P2X and P2Y Receptors

Tocris Scientific Review Series Tocri-lu-2945 P2X and P2Y Receptors Kenneth A. Jacobson Subtypes and Structures of P2 Receptor Molecular Recognition Section, Laboratory of Bioorganic Families Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and The P2 receptors for extracellular nucleotides are widely Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, distributed in the body and participate in regulation of nearly Maryland 20892, USA. E-mail: [email protected] every physiological process.1,2 Of particular interest are nucleotide Kenneth Jacobson serves as Chief of the Laboratory of Bioorganic receptors in the immune, inflammatory, cardiovascular, muscular, Chemistry and the Molecular Recognition Section at the National and central and peripheral nervous systems. The ubiquitous Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National signaling properties of extracellular nucleotides acting at two Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Dr. Jacobson is distinct families of P2 receptors – fast P2X ion channels and P2Y a medicinal chemist with interests in the structure and receptors (G-protein-coupled receptors) – are now well pharmacology of G-protein-coupled receptors, in particular recognized. These extracellular nucleotides are produced in receptors for adenosine and for purine and pyrimidine response to tissue stress and cell damage and in the processes nucleotides. of neurotransmitter release and channel formation. Their concentrations can vary dramatically depending on circumstances. Thus, the state of activation of these receptors can be highly dependent on the stress conditions or disease states affecting a given organ. The P2 receptors respond to various extracellular mono- and dinucleotides (Table 1). The P2X receptors are more structurally restrictive than P2Y receptors in agonist selectivity. -

NPTC Formulary Brief

Indian Health Service National Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Formulary Brief: Oral Antiplatelet Agents May 2015 The NPTC performed a class review of oral antiplatelet agents at the May meeting. This class of medications was last reviewed in March 2011. Since that time, ticagrelor received FDA approval. Oral antiplatelet agents include aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticlopidine, and ticagrelor. Ticlopidine is no longer recommended as a first line agent as it has many life threatening hematologic adverse reactions, and thus, was not included in the review. Aspirin was also not included in the review. Clopidogrel is the only (non-aspirin) oral antiplatelet agent currently named on the National Core Formulary (NCF). Discussion: All three agents reviewed are FDA-approved for thrombosis prophylaxis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) managed with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Ticagrelor and clopidogrel are also approved for thrombosis prophylaxis in ACS managed without PCI. Clopidogrel has the most FDA- approved indications, including ACS, acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), stroke, recent myocardial infarction (MI) and peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Clopidogrel is the only agent studied in patients undergoing fibrinolysis. Both prasugrel (Wiviott, 2007) and ticagrelor (Wallentin, 2009) have been associated with lower rates of cardiovascular (CV) events and stent thrombosis than clopidogrel. Prasugrel has shown a marked benefit over clopidogrel in patients with diabetes. Prasugrel is also associated with a higher rate of bleeding than clopidogrel. Patients with a history of stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), weight less than 60 kilograms or age greater than or equal to 75 years should not receive prasugrel because risks outweigh the benefits. -

Use of Clopidogrel, Prasugrel, Or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcome After Acute Coronary Syndrome in Austria from 2015 to 2017

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Use of Clopidogrel, Prasugrel, or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcome after Acute Coronary Syndrome in Austria from 2015 to 2017 Safoura Sheikh Rezaei 1, Andreas Gleiss 2, Berthold Reichardt 3 and Michael Wolzt 1,* 1 Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 2 Center for Medical Statistics, Informatics, and Intelligent Systems, Medical University of Vienna, Spitalgasse 23, 1090 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 3 Austrian Health Insurance Fund, Burgenland, Siegfried Marcus-Straße 5, 7000 Eisenstadt, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-(0)1-40400-29810; Fax: +43-(0)1-40400-29980 Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Background: Dual antiplatelet therapy improves patient outcome after acute coronary syndrome (ACS), but prescription differences of P2Y12 inhibitor treatments exist. The aim of the present investigation was to study the long-term utilization and patient outcomes of clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor in patients with ACS from 2015 to 2017 in Austria. Methods: Data from 13 Austrian health insurance funds of patients with a hospital discharge diagnosis of ACS for the years 2015 to 2017 were analyzed. The primary end point was to investigate the recurrence of ACS or death. Results: Of 49,124 P2Y12 inhibitor-naive patients with a hospital discharge diagnosis of ACS, 25,147 subjects filled a P2Y12 inhibitor prescription within 30 days after the index event. Of these patients, 10,626 (42.9%) subjects had a prescription for clopidogrel, 4788 (19.3%) for prasugrel, and 9383 (37.8%) for ticagrelor. -

Development of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Identification of Patients at Risk for Medication Transfer Errors at ICU Discharge

RESEARCH ARTICLE Development of a multivariable prediction model for identification of patients at risk for medication transfer errors at ICU discharge 1,2 1,3 2,4 Liesbeth B. E. BosmaID *, Nienke van Rein , Nicole G. M. Hunfeld , Ewout W. Steyerberg5, Piet H. G. J. Melief6, Patricia M. L. A. van den Bemt2 1 Haga Teaching Hospital, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Els Borst-Eilersplein CH, The Hague, The Netherlands, 2 Erasmus University Medical Center, Department of Hospital Pharmacy, CA, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 3 Leiden University Medical Center, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Toxicology, Leiden, The Netherlands, 4 Erasmus University Medical Center, Department of Intensive Care, CA, Rotterdam, The a1111111111 Netherlands, 5 Clinical Biostatistics and Medical Decision Making at Erasmus MC, Rotterdam and Leiden a1111111111 University Medical Center, ZA Leiden, The Netherlands, 6 Haga Teaching Hospital, Department of Intensive Care, CH, The Hague, The Netherlands a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 Abstract OPEN ACCESS Introduction Citation: Bosma LBE, van Rein N, Hunfeld NGM, Steyerberg EW, Melief PHGJ, van den Bemt PMLA Discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU) is a high-risk process, leading to numerous (2019) Development of a multivariable prediction potentially harmful medication transfer errors (PH-MTE). PH-MTE could be prevented by model for identification of patients at risk for medication reconciliation by ICU pharmacists, but resources are scarce, which renders the medication transfer errors at ICU discharge. PLoS ONE 14(4): e0215459. https://doi.org/10.1371/ need for predicting which patients are at risk for PH-MTE. The aim of this study was to journal.pone.0215459 develop a prognostic multivariable model in patients discharged from the ICU to predict who Editor: Shane Patman, University of Notre Dame is at increased risk for PH-MTE after ICU discharge, using predictors of PH-MTE that are Australia, AUSTRALIA readily available at the time of ICU discharge.