The Indigenous Experience on the Goldfields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

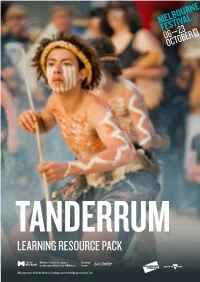

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Racist Structures and Ideologies Regarding Aboriginal People in Contemporary and Historical Australian Society

Master Thesis In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science: Development and Rural Innovation Racist structures and ideologies regarding Aboriginal people in contemporary and historical Australian society Robin Anne Gravemaker Student number: 951226276130 June 2020 Supervisor: Elisabet Rasch Chair group: Sociology of Development and Change Course code: SDC-80436 Wageningen University & Research i Abstract Severe inequalities remain in Australian society between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. This research has examined the role of race and racism in historical Victoria and in the contemporary Australian government, using a structuralist, constructivist framework. It was found that historical approaches to governing Aboriginal people were paternalistic and assimilationist. Institutions like the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines, which terrorised Aboriginal people for over a century, were creating a racist structure fuelled by racist ideologies. Despite continuous activism by Aboriginal people, it took until 1967 for them to get citizens’ rights. That year, Aboriginal affairs were shifted from state jurisdiction to national jurisdiction. Aboriginal people continue to be underrepresented in positions of power and still lack self-determination. The national government of Australia has reproduced historical inequalities since 1967, and racist structures and ideologies remain. ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Elisabet Rasch, for her support and constructive criticism. I thank my informants and other friends that I met in Melbourne for talking to me and expanding my mind. Floor, thank you for showing me around in Melbourne and for your never-ending encouragement since then, via phone, postcard or in person. Duane Hamacher helped me tremendously by encouraging me to change the topic of my research and by sharing his own experiences as a researcher. -

Dialogue and Indigenous Policy in Australia

Dialogue and Indigenous Policy in Australia Darryl Cronin A thesis in fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Policy Research Centre Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences September 2015 ABSTRACT My thesis examines whether dialogue is useful for negotiating Indigenous rights and solving intercultural conflict over Indigenous claims for recognition within Australia. As a social and political practice, dialogue has been put forward as a method for identifying and solving difficult problems and for promoting processes of understanding and accommodation. Dialogue in a genuine form has never been attempted with Indigenous people in Australia. Australian constitutionalism is unable to resolve Indigenous claims for recognition because there is no practice of dialogue in Indigenous policy. A key barrier in that regard is the underlying colonial assumptions about Indigenous people and their cultures which have accumulated in various ways over the course of history. I examine where these assumptions about Indigenous people originate and demonstrate how they have become barriers to dialogue between Indigenous people and governments. I investigate historical and contemporary episodes where Indigenous people have challenged those assumptions through their claims for recognition. Indigenous people have attempted to engage in dialogue with governments over their claims for recognition but these attempts have largely been rejected on the basis of those assumptions. There is potential for dialogue in Australia however genuine dialogue between Indigenous people and the Australian state is impossible under a colonial relationship. A genuine dialogue must first repudiate colonial and contemporary assumptions and attitudes about Indigenous people. It must also deconstruct the existing colonial relationship between Indigenous people and government. -

In Good Faith? Governing Indigenous Australia Through God, Charity and Empire, 1825-1855

In Good Faith? Governing Indigenous Australia through God, Charity and Empire, 1825-1855 In Good Faith? Governing Indigenous Australia through God, Charity and Empire, 1825-1855 Jessie Mitchell THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 23 This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/good_faith_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Mitchell, Jessie. Title: In good faith? : governing Indigenous Australia through god, charity and empire, 1825-1855 / Jessie Mitchell. ISBN: 9781921862106 (pbk.) 9781921862113 (eBook) Series: Aboriginal history monograph ; 23 Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Indigenous peoples--Government relations. Philanthropinism. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Aboriginal Australians--Social conditions--19th century. Colonization--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.89915 Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Kaye Price (Chair), Peter Read (Monographs Editor), Maria Nugent and Shino Konishi (Journal Editors), Robert Paton (Treasurer and Public Officer), Anne McGrath (Deputy Chair), Isabel McBryde, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Harold Koch, Christine Hansen, Tikka Wilson, Geoff Gray, Jay Arthur, Dave Johnson, Ingereth Macfarlane, Brian Egloff, Lorena Kanellopoulos, Richard Baker, Peter Radoll. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: Thelma Sims, email: Thelma.Sims@anu. edu.au, tel or fax: +61 2 6125 3269, www.aboriginalhistory.org Aboriginal History Inc. -

Thematic Environmental History Aboriginal History

THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY ABORIGINAL HISTORY Prepared for City of Greater Bendigo FINAL REPORT June 2013 Adopted by City of Greater Bendigo Council July 31, 2013 Table of Contents Greater Bendigo’s original inhabitants 2 Introduction 2 Clans and country 2 Aboriginal life on the plains and in the forests 3 Food 4 Water 4 Warmth 5 Shelter 6 Resources of the plains and forests 6 Timber 6 Stone 8 The daily toolkit 11 Interaction between peoples: trade, marriage and warfare 12 British colonisation 12 Impacts of squatting on Aboriginal people 13 Aboriginal people on the goldfields 14 Aboriginal Protectorates 14 Aboriginal Reserves 15 Fighting for Identity 16 Authors/contributors The authors of this history are: Lovell Chen: Emma Hewitt, Dr Conrad Hamann, Anita Brady Dr Robyn Ballinger Dr Colin Pardoe LOVELL CHEN 2013 1 Greater Bendigo’s original inhabitants Introduction An account of the daily lives of the area’s Aboriginal peoples prior to European contact was written during the research for the Greater Bendigo Thematic Environmental History to achieve some understanding of life before European settlement, and to assist with tracing later patterns and changes. The repercussions of colonialism impacted beyond the Greater Bendigo area and it was necessary to extend the account of this area’s Aboriginal peoples to a Victorian context, including to trace movement and resettlement beyond this region. This Aboriginal history was drawn from historical records which include the observations of the first Europeans in the area, who documented what they saw in writing and sketches. Europeans brought their own cultural perceptions, interpretations and understandings to the documentation of Aboriginal life, and the stories recorded were not those of the Aboriginal people themselves. -

Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870

Black Gold Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870 Fred Cahir Black Gold Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870 Fred Cahir Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 25 This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cahir, Fred. Title: Black gold : Aboriginal people on the goldfields of Victoria, 1850-1870 / Fred Cahir. ISBN: 9781921862953 (pbk.) 9781921862960 (eBook) Series: Aboriginal history monograph ; 25. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Gold mines and mining--Victoria--1851-1891. Aboriginal Australians--Victoria--History--19th century. Dewey Number: 994.503 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Published with the assistance of University of Ballarat (School of Business), Sovereign Hill Parks and Museum Association and Parks Victoria This publication has been supported by the Australian Historical Association Cover design with assistance from Evie Cahir Front Cover photo: ‘New diggings, Ballarat’ by Thomas Ham, 1851. Courtesy State Library of Victoria Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Preface and acknowledgements . .vii Introduction . 1 1 . Aboriginal people and mining . 5 2 . Discoverers and fossickers . 21 3 . Guiding . 35 4 . Trackers and Native Police . 47 Illustrations . 57 5 . Trade, commerce and the service sector . 67 6 . Co-habitation . 85 7. Off the goldfields . 103 8 . Social and environmental change . 109 9 . -

Caves in Victorian Aboriginal Social Organization Ian D

Helictite, (2007) 40(1): 3-10 The abode of malevolent spirits and creatures - Caves in Victorian Aboriginal social organization Ian D. Clark School of Business, University of Ballarat, PO Box 663, Ballarat Vic 3353, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract A study of Aboriginal associations with Victorian caves finds that there is a rich cultural heritage associated with caves. This association has been found to be rich and varied in which caves and sink holes featured prominently in the lives of Aboriginal people – they were often the abodes of malevolent creatures and spirits and some were associated with important ancestral heroes, traditional harming practices, and some were important in the after death movement of souls to their resting places. Aboriginal names for caves, where known, are discussed. Keywords: rock shelters, caves, dark zones, Aboriginal heritage, mythology, Victoria, Australia. Introduction Clark, 2000a) entered the following account of his visit to the Widderin Caves south of Skipton: This paper documents Aboriginal associations with caves in Victoria through considering their place in ... visited the caves. Mr Anderson’s brother went with stories and mythology and also through examining place me. The entrance is a half mile from Weerteering west. names of caves. Rock shelters, commonly called caves, The entrance is in a large hole, 60 by 50. Very large tree are a rich repository of Aboriginal cultural heritage. mallee, 10 to 12 feet high, the largest indigenous tree However, this study will attempt to follow the narrower mallee I have ever seen. The bats during in last month usage of ‘cave’ employed by most cavers, that is, they were seen in thousands; there were only three at this must have a dark zone, but it needs to be acknowledged time. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

Parliamentary Inquiry Into Biodiversity Loss And

Dr. Tamasin Ramsay (PhD) Medical Anthropologist PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY INTO BIODIVERSITY LOSS AND ECOSYSTEM DECLINE 30TH AUGUST 2020 This submission begins with an anthropological review of our current crisis, recognizing the recent silo focus on human interests. Following this are the five key drivers of biodiversity loss and ecosystem decline: exploitation, habitat loss, pollution, introduced species and climate change. The submission then identifies detrimental actions that are perpetuating our current predicament, and suggests restorative actions that can help facilitate a recovery. The summary calls for robust legislation, and offers four recommendations including supporting farmers in transitioning towards plant agriculture, incorporating First Nations culture and care for Country, re‐introducing the Dingo as apex predator, and restoring the natural sense ofr wonde that exists in the naturally life‐affirming human. TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Background _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Preface _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________1 Author Introduction ______________________________________________________________________________________________1 Submission Structure _____________________________________________________________________________________________1 Submission _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 2 The Anthropocene ________________________________________________________________________________________________2 -

Aboriginal Languages 1

Aboriginal Languages 1 How many languages? Outline of the course 1 How many languages? The number of languages and how they are related 2 Pronunciation The sounds and the ways they are represented Borrowing English words into Aboriginal sound systems 3 Grammar Word building (compounding, affixation) Syntax 4 Vocabulary Words and meanings Language survival and reclamation Extending the vocabulary 2 Sahul 3 3 Sahul 2 Changes in sea level 5 Sahul to Australia 40,000 BP 14,000 BP 10,000 BP 6 • In1858 an Aborigine, named Murray, Aboriginal stories pointed out that the channel that ships used to sail up Port Phillip Bay was the bed of the Yarra River and that at one time the Yarra flowed through the heads until the sea broke in and flooded the bay. • Apparently, Port Phillip Bay was mainly dry about a thousand years ago, not because of a low sea level, but because the entrance to the bay being silted up 7 • To Aboriginal people the craters of volcanoes were seen as the sites of camp fires or ovens of giants. The Aboriginal stories Boandik people of south-eastern South Australia tell of the giant, Craitbul, forced to abandon his fire on top of Mt Muirhead (near Millicent), because it would no longer stay alight. He and his people moved to Mt Schank (south of Mt Gambier) where he built a new campfire, but this fire did not last, and again he had to move, and he moved to Mt Gambier where his four attempts to establish a campfire were thwarted by rising water. -

Indigenous Perspective 'Tuckerbag'

INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE ‘TUCKERBAG’ A COMPREHENSIVE AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM RESOURCE COMPANION www.koorieheritagetrust.com Background Together with Koorie Heritage Trust, the Hawthorn Football Club are proud to provide a resource document for those wanting to build on their knowledge of Indigenous Australia. The following resource has been created to ‘Protect, Preserve and Promote’ Aboriginal culture from South Eastern Australia. Therefore, a significant number of these resources are from this area. Contents Page GENERAL 4 PROTOCOLS/ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 LANGUAGES/PLACE NAMES/MAPS/FLAGS ABORIGINAL CULTURAL ORGANISATIONS VICTORIA MUSEUM AND LIBRARY RESOURCES 6 MEDIA INDIGENOUS MARCHES EMPOWERMENT/ HUMAN RIGHTS 7 ABORIGINAL LEADERS 1967 REFERENDUM CASE STUDIES-:BUDJ BIM/ LAKE CONDAH CORANDERRK 9 CROSS CURRICULUM LINKS THE NT INTERVENTION 10 STOLEN GENERATIONS ENGLISH/HISTORY 11 MATHEMATICS SCIENCE HEALTH AND PHYSICAL EDUCATION 12 THE ARTS/MUSIC/ART/PERFORMANCE KOORIE CREATION STORIES 13 INITIATION SOCIAL ORGANISATION WALERT GURN (Possum Skin Cloak) BUSH MEDICINE 14 ASTRONOMY ABORIGINAL INVENTIONS TECHNOLOGY TRADE INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS AT WAR 15 POLICIES WRITTEN TEXTS 16 NEWSPAPERS AND JOURNALS CD and DVD list ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 17 GENERAL ACARA Australian Curriculum, Assessment and https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum Reporting Authority http://victoriancurriculum.vcaa.vic.edu.au/static/docs/Learning%20about%20Abori ginal%20and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20Histories%20and%20Cultures.pdf Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Inc. www.vaeai.org.au