The Lexicon Graph Model a Generic Model for Multimodal Lexicon Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Journal.Finfar.Org

ISSN: 2342-2009 Fafnir vol 3, iss 4, pages 7–227–23 Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research journal.finfar.org Speculative Architectures in Comics Francesco-Alessio Ursini Abstract: The present article offers an analysis on how comics authors can employ architecture as a narrative trope, by focusing on the works of Tsutomu Nihei (Blame!, Sidonia no Kishi), and the duo of Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters (Le cités obscures). The article investigates how these authors use architectural tropes to create speculative fictions that develop renditions of cities as complex narrative environments, and “places” with a distinctive role and profile in stories. It is argued that these authors exploit the multimodal nature of comics and the potential of architecture to construct complex worlds and narrative structures. Keywords: architectural tropes, comics, narrative structure, speculative fiction, world-building, multimodality Biography and contact info: Francesco-Alessio Ursini is currently a lecturer in English linguistics and literature at Jönköping University. His works on comics include a special issue on Grant Morrison for the journal ImageTexT, and the forthcoming Visions of the Future in Comics (McFarland Press), both co-edited with Frank Bramlett and Adnan Mahmutović. Speculative fiction and comics have always been tightly connected across different cultural traditions. It has been argued that the “golden era” of manga (Japanese comics) in the 70’s and 80’s is based on the preponderance of works using science/speculative fiction settings (e.g. Akira, Ohsawa 9–26). Similarly, classic works in the “Latin” comic traditions (i.e. Latin American historietas, Italian fumetti, and French/Belgian bande desineés) have long represented an ideal nexus between the speculative fiction genre and the Comics medium, one example being El Eternauta (Page 46–50). -

Transhumanity's Fate

ECLIPSE PHASE: TRANSHUMANITY’S FATE The Fate Conversion Guide for Eclipse Phase RYAN JACK MACKLIN GRAHAM ECLIPSE PHASE: TRANSHUMANITY’S FATE Transhumanity’s Fate: ■ Brings technothriller espionage and horror in a world of upgraded humans to Fate Core. ■ Join Firewall, and defend transhumanity in the aftermath of near annihilation by arti cial intelligence. ■ Requires Fate Core to play. Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Transhumanity’s Fate is © 2016. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License. Fate™ is a trademark of Evil Hat Productions, LLC. The Powered by Fate logo is © Evil Hat Productions, LLC and is used with permission. eclipsephase.com TRANSHUMANITY'S FATE WRITING DEDICATION Jack Graham, Ryan Macklin The Posthumans dedicate this book to Jef Smith, our ADDITIONAL MATERIAL companion of many days & nights around the table. Jef was a tireless organizer in Chicago's science-fiction/ Rob Boyle, Caleb Stokes fantasy fandom, including the Think Galactic reading EDITING group and spin-off convention, Think Galacticon. In Rob Boyle, Jack Graham 2015, he co-published the Sisters of the Revolution: A GRAPHIC DESIGN Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology with PM Press. Adam Jury We will miss Jef's encouragement, wit, and bottomless COVER ART generosity. The person who lives large in the lives of their friends is not soon forgotten. Stephan Martiniere A portion of profits from Transhumanity's Fate will be INTERIOR ART donated to Jef's family. Rich Anderson, Nic Boone, Leanne Buckley, Anna Christenson, Daniel Clarke, Paul Davies, SPECIAL THANKS Alex Drummond, Danijel Firak, Nathan Geppert, Ryan thanks his wife, Lillian, for her support and Zachary Graves, Tariq Hassan, Josu Hernaiz, octomorph shenanigans, and blackcoat for being a font Jason Juta, Sergey Kondratovich, Ian Llanas, of feedback. -

The Tragedy of the Megastructure

105 Megastructures 3 | 2018 | 1 The Tragedy of the Megastructure Valentin Bourdon PhD Candidate École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne [email protected] Valentin Bourdon is a PhD student at the Laboratory of Construction and Conservation (LCC) EPFL since 2017. His research explores the architectural challenges of the common space. In support of significant historical experiences, and contemporary subjects, such a project aims to help overcome the delay taken by architecture comparing to other disciplines in the appropriation of the notion of ‘common’. ABSTRACT Relating the megastructure to the issue of the commons is a useful exercise to understand the success and the disappearance of what Peter Reyner Banham called the “dinosaurs of the Modern Movement”. All these large-scale constructions suffered the same fate: a conflict between the promise of a large shared space and the temptation of its fragmentation. This quantitative quandary is also raised in another field by Garrett Hardin in 1968 as the ‘enclosure dilemma’. The publication of his article “The Tragedy of the Commons” sparked a broad controversy coinciding with the megastructure’s momentum. By assessing a number of theoretical correspondences, the article reexamines the impact of megastructures on the interdisciplinary debates of the time. It also considers the relationship between architecture and property as one of the possible–and tragically coincident–reasons for their success and dissolution. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2611-0075/8523 ISSN 2611-0075 Copyright © 2018 Valentin Bourdon 4.0 KEYWORDS Megastructure; Commons; Ownership; Enclosure; Anti-enclosure. Valentin Bourdon The Tragedy of the Megastructure 106 When the American ecologist Garrett Hardin publishes his famous article entitled “The Tragedy of the Commons”1 in Science, the architectural 1. -

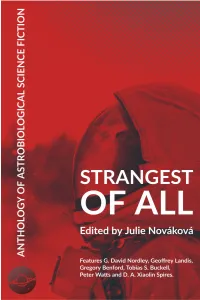

Strangest of All

Strangest of All 1 Strangest of All TRANGEST OF LL AnthologyS of astrobiological science A fiction ed. Julie Nov!"o ! Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute Features G. %avid Nordley& Geoffrey Landis& Gregory 'enford& Tobias S. 'uc"ell& (eter Watts and %. A. *iaolin S#ires. + Strangest of All , Strangest of All Edited originally for the #ur#oses of 'EACON +.+.& a/conference of the Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute 0EA$1. -o#yright 0-- 'Y-N--N% 4..1 +.+. Julie No !"o ! 2ou are free to share this 5or" as a 5hole as long as you gi e the ap#ro#riate credit to its creators. 6o5ever& you are #rohibited fro7 using it for co77ercial #ur#oses or sharing any 7odified or deri ed ersions of it. 8ore about this #articular license at creati eco77ons.org9licenses9by3nc3nd94.0/legalcode. While this 5or" as a 5hole is under the -reati eCo77ons Attribution3 NonCo77ercial3No%eri ati es 4.0 $nternational license, note that all authors retain usual co#yright for the indi idual wor"s. :$ntroduction; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :)ar& $ce& Egg& =ni erse; < +..+ by G. %a id Nordley :$nto The 'lue Abyss; < 1>>> by Geoffrey A. Landis :'ac"scatter; < +.1, by Gregory 'enford :A Jar of Good5ill; < +.1. by Tobias S. 'uc"ell :The $sland; < +..> by (eter )atts :SET$ for (rofit; < +..? by Gregory 'enford :'ut& Still& $ S7ile; < +.1> by %. A. Xiaolin S#ires :After5ord; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :8artian Fe er; < +.1> by Julie No !"o ! 4 Strangest of All :@this strangest of all things that ever ca7e to earth fro7 outer space 7ust ha e fallen 5hile $ 5as sitting there, isible to 7e had $ only loo"ed u# as it #assed.; A H. -

Strategy and Spell Art As Infrastructural Change

Strategy and Spell Art as Infrastructural Change Luiza Crosman, MA in Art and Culture Researcher at The Terraforming Strelka Institute The essay “Strategy and Spell: Art as Infrastructural Change” is an investi- gation of the performative force art spaces have on the field of art and on various infrastructures at large. It is also a strategic proposition on how to envision a position for action and from which to gain leverage within the current neoliberal global context. Drawing from contemporary art, design and media theory on systemic thinking, and the post-contemporary time complex, the essay reflects on two personal projects: the exhibition space casamata (2014–2017), and the project TRAMA, developed for the 33rd São Paulo Biennial – Affective Affinities (2018). Favoring a speculative approach that tackles large-scale problematics and collective organization, it demon- strates how there are many potentialities contained in exhibition spaces and how such potentialities could, through an understanding of a contemporary art megastructure and art practice as infrastructural change, operate new experiments for the art system. Introduction Why is contemporary art’s internal operational system still one of power inequality and economic precarity despite its visual and discursive pro- duction being critical of political injustices and social stratification? This essay will argue that there is an overpowering system in place, which is not affected by the current visual or discursive production, and which can actually benefit from it. Because of that, the question becomes, how can art production engage with the world not only as a symbolic or visual system, but also through its potent infrastructure? PASSEPARTOUT—NEW INFRASTRUCTURES 29 This essay will think through transformative action propositions by way of two personal reflections derived from my own artistic practice, and extricate from these instructable examples that can be used, in abstract terms, as a way to propose a base model from which to work upon as an artist. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Conditions of the Hong Kong Section: Spatial History and Regulatory Environment of Vertically Integrated Developments Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/43t4721n Author Tan, Zheng Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Conditions of the Hong Kong Section: Spatial History and Regulatory Environment of Vertically Integrated Developments A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Zheng Tan 2014 © Copyright by Zheng Tan 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Conditions of the Hong Kong Section: Spatial History and Regulatory Environment of Vertically Integrated Developments by Zheng Tan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Dana Cuff, Chair This dissertation explores the urbanism of Hong Kong between 1967 and 1997, tracing the history of Hong Kong’s vertically integrated developments. It inquires into a Hong Kong myth: How can minimum state intervention gather social resources to build collective urban form? Roughly around the MacLehose Era, Hong Kong began to consciously assume a new vertical order in urban restructuring in order to address the issue of over-crowding and social unrest. British modernist planning provided rich approaches and visions which were borrowed by Hong Kong to achieve its own planning goals. The new town plan and infrastructural development ii transformed Hong Kong from a colonial city concentrated on the Victoria Harbor to a multi-nucleated metropolitan area. The implementation of the R+P development model around 1980 deepened the intermingling between urban infrastructure and superstructure and extended the vertical urbanity to large interior spaces: the shopping centers. -

Megastructures

n.3 2018 vol.I Megastructures Dominique Rouillard edited by Wolfgang Fiel Dominique Rouillard Xavier Van Rooyen Anna Rosellini Francesco Zuddas Lorenzo Ciccarelli Lorenzo Diana Beatrice Lampariello Valentin Bourdon Scientific Commitee Editorial Team Nicholas Adams (Vassar College), Micaela Antonucci Histories of Ruth Baumeister (Aarhus School abstract and paper submission editor of Architecture), Francesco Benelli Stefano Ascari (Università di Bologna), Eve Blau graphic and design editor Postwar (Harvard University), Federico Bucci, Politecnico di Milano, Matteo Cassani Simonetti Maristella Casciato (Getty images manager Architecture Research Institute), Pepa Cassinello Lorenzo Ciccarelli (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid), editorial assistant ISSN 2611-0075 Carola Hein (Delft University of https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2611-0075/v1-n3-2018 Technology), Helene Janniere Elena Formia (Université Rennes 2), Giovanni communication manager Leoni (Università di Bologna), Beatrice Lampariello Thomas Leslie (Iowa State editorial assistant University), Mary Caroline McLeod (Columbia University), Daniel J. Sofia Nannini Naegele (Iowa State University), editorial assistant Joan Ockman (Penn University), Gabriele Neri Antoine Picon (Harvard Graduate editorial assistant School of Design), Antonio Pizza (Escola Tècnica Superior Anna Rosellini paper review and publishing editor under the auspices of d’Arquitectura de Barcelona), Dominique Rouillard (Ecole Matteo Sintini Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture journal manager de Paris Malaquais), Paolo Scrivano (Xi’an Jiaotong University - Ines Tolic University of Liverpool), Laurant abstract and paper submission editor Stalder (ETH Zurich), Martino AISU Stierli (MoMA), Rosa Tamborrino, Associazione Italiana di Storia Urbana Politecnico di Torino, André Carinha Tavares (Universidade do Minho), Letizia Tedeschi, (Archivio del Moderno, Università della Svizzera Italiana), Herman van Bergeijk, AISTARCH (Delft University of Technology), Società Italiana di Storia dell’Architettura Christophe van Gerrewey (EPFL). -

Searches for Life and Intelligence Beyond Earth

Technologies of Perception: Searches for Life and Intelligence Beyond Earth by Claire Isabel Webb Bachelor of Arts, cum laude Vassar College, 2010 Submitted to the Program in Science, Technology and Society in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2020 © 2020 Claire Isabel Webb. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________________ History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society August 24, 2020 Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ David Kaiser Germeshausen Professor of the History of Science (STS) Professor of Physics Thesis Supervisor Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ Stefan Helmreich Elting E. Morison Professor of Anthropology Thesis Committee Member Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ Sally Haslanger Ford Professor of Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies Thesis Committee Member Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________ Graham Jones Associate Professor of Anthropology Director of Graduate Studies, History, Anthropology, and STS Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________ -

Warp-Drive-KIC8462852-Part2.Pd

Is the Natario warp drive a valid candidate for an interstellar voyage to the star system KIC8462852??-Part II Fernando Loup To cite this version: Fernando Loup. Is the Natario warp drive a valid candidate for an interstellar voyage to the star system KIC8462852??-Part II. [Research Report] Residencia de Estudantes Universitas. 2016. hal-01351011 HAL Id: hal-01351011 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01351011 Submitted on 2 Aug 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Is the Natario warp drive a valid candidate for an interstellar voyage to the star system KIC8462852??-Part II Fernando Loup ∗ Residencia de Estudantes Universitas Lisboa Portugal August 2, 2016 Abstract In 2009 the Kepler Space Telescope was launched into space to look for extra-solar planets around distant stars. The portion of the sky covered by the Kepler Space Telescope was(and still is) a small region between the constellations of Cygnus and Lyra.When the Kepler analyzed the star KIC8462852 an anomaly was detected in the starlight distribution with an occultation that reduces the flux of light by 20 percent. Such anomaly as far as we know cannot be explained by natural causes. -

Takis Zenetos's Electronic Urbanism and Tele-Activities

Article Takis Zenetos’s Electronic Urbanism and Tele-Activities: Minimizing Transportation as Social Aspiration Marianna Charitonidou 1,2,3 1 Chair of the History and Theory of Urban Design, Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), Department of Architecture, ETH Zurich, CH 8093 Zürich, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 School of Architecture, National Technical University of Athens, 42 Patission Street, 106 82 Athens, Greece 3 Faculty of Art History and Theory, Athens School of Fine Arts, 42 Patission Street, 106 82 Athens, Greece Abstract: Takis Zenetos was enthusiastic about the idea of working from home, and believed that both architecture and urban planning should be reshaped in order to respond to this. He supported the design of special public spaces in residential units, aiming to accommodate the inhabitants during working hours. This article argues that Zenetos’s design for “Electronic Urbanism” was more prophetic, and more pragmatic, than his peers such as Archigram and Constant Nieuwenhuys. Despite the fact that they shared an optimism towards technological developments and megastruc- ture, a main difference between Zenetos’s view and the perspectives of his peers is his rejection of a generalised enthusiasm concerning increasing mobility of people. In opposition with Archigram, Zenetos insisted in minimizing citizens’ mobility and supported the replacement of daily transport with the use advanced information technologies, using terms such as “tele-activity”. Zenetos was convinced that “Electronic Urbanism” would help citizens save the time that they normally used to commute to work, and would allow them to spend this time on more creative activities, at or near their homes. -

System Engineering Analysis of Terraforming Mars with an Emphasis on Resource Importation Technology

LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 System Engineering Analysis of Terraforming Mars with an Emphasis on Resource Importation Technology Brandon Wong Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd Part of the Systems Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Wong, Brandon, "System Engineering Analysis of Terraforming Mars with an Emphasis on Resource Importation Technology" (2018). LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations. 888. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd/888 This Research Projects is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. System Engineering Analysis of Terraforming Mars with an Emphasis on Resource Importation Technology Loyola Marymount University, Systems Engineering Leadership Program Capstone Project Abstract This project uses System Engineering principles to delve into the viability of different methods for Terraforming Mars, with a comparison between Paraterraforming, Terraforming and Bioforming. It will then examine one subsystem that will be integral to the terraforming process, which is the space infrastructure necessary to import enough gases to recreate Earth’s atmosphere on Mars. It will analyze the viability of Chemical Rockets, Nuclear Rockets, Space -

Alien Megastructures: the Possibility of Extraterrestrial Life and the Rhetoric of Hope in the Anthropocene

Alien Megastructures: The Possibility of Extraterrestrial Life and the Rhetoric of Hope in the Anthropocene Andrew Pilsch Today I want to discuss the relationship between hope, climate change, geo-engineering and the possibility of alien civilization. Moreover, I want to think of the latter two phenomenon as emblematic of a rhetoric of hope in the age of dire climate emergency. Specifically, I want to talk about the phenomenon surrounding Tabby’s Star. Officially designated KIC 8462852, Tabby’s Star was identified by Planet Hunters, a group of citizen scientists sifting large quantities of astronomical data for evidence of exo-planets, and has since gained a reputation as “the most mysterious star in the universe,” as Tabetha Boyajian, the star’s namesake and lead scientific investigator, has declared. Tabby’s Star, an F-class sun (bigger and hotter than our own) 1500 light-years from Earth in SLOW DOWN 2 the Cygnus constellation, periodically dims. Periodic dimming is often the sign of exoplanets, as the planets move in front of the particular star and this is why Kepler, the space telescope set up to look for these phenomena, first noticed Tabby’s Star. What makes Tabby’s Star so particularly compelling is that it periodically dims at a rate much greater than what would be seen with orbiting planets. While this would have, and still is, a major boon for academic astronomy research, with numerous papers speculating on the natural phenomenon that could be causing the dimming of Tabby’s Star, one paper, published in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement by a team at Penn State, speculated that the mysterious periodic dimming of Tabby’s Star could be the result of a Dyson sphere.