UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENIDO Por AUTOR

ÍNDICE de CONTENIDO por AUTOR Arquitectos de México Autor Artículo No Pg A Abud, Antonio Casa habitación 04/5 44 Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y una breve descripción. Abud, Antonio Casa habitación (2) 04/05 48 Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y una breve descripción. Abud, Antonio Edificio de apartamentos 04/05 52 Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y una breve descripción. Abud Nacif, Edificio de productos en la 11 56 Antonio Ciudad de México Explica el problema y la solución, ilustrado con plantas arquitectónicas y una fotografía. Almeida, Héctor F. Residencia en el Pedregal de 11 24 San Ángel Plantas arquitectónicas y fotografías con una breve explicación. Alvarado, Carlos, Conjunto habitacional en 04/05 54 Simón Bali, Jardín Balbuena Ramón Dodero y Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y Germán Herrasti. descripción. Álvarez, Augusto H. Edificio de oficinas en Paseo de 24 52 la Reforma Explica el problema y la solución ilustrado con planos y fotografías. Arai, Alberto T. Edificio de la Asociación México 08 30 – japonesa Explica el problema y el proyecto, ilustrado con planos arquitectónicos y fotografías. Arnal, José María Cripta. 07 38 y Carlos Diener Describen los objetivos del proyecto ilustrado con planta arquitectónica y una fotografía. 11 Autor Artículo No Pg Arrigheti, Arrigo Barrio San Ambrogio, Milán 26 18 Describe el problema y el proyecto, ilustrado con planos y fotografías. Artigas Francisco Residencia en Los Angeles, 12 34 Calif. Explica el proyecto ilustrado con plantas arquitectónicas y fotografías. Artigas, Francisco Mausoleo a Jorge Negrete 09/10 17 Una foto con un pensamiento de Carlos Pellicer. Artigas, Francisco 13 casas habitación 09/10 18 Risco 240, Agua 350, Prior 32 (Casa del arquitecto Artigas), Carmen 70, Agua 868, Paseo del Pedregal 511, Agua 833, Paseo del Pedregal 421, Reforma 2355, Cerrada del Risco 151, Picacho 420, Nubes 309 y Tepic 82 Todas en la Ciudad de México ilustradas con planta arquitectónica y fotografías. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

HYATT REGENCY HONG KONG, SHA TIN 18 Chak Cheung Street, Sha Tin, New Territories, Hong Kong, People’S Republic of China

HYATT REGENCY HONG KONG, SHA TIN 18 Chak Cheung Street, Sha Tin, New Territories, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China T: +852 3723 1234 F: +852 3723 1235 E: [email protected] hyattregencyhongkongshatin.com ACCOMMODATION RECREATIONAL FACILITIES • 430 guestrooms and suites with harbour and mountain views • Melo Spa and “Melo Moments” for sparties • 132 specially designed rooms and suites for extended stays • Fitness centre, sauna and steam rooms • Wall-mounted retractable LCD TV • Outdoor swimming pool with sundeck and whirlpool • In-room safe • Camp Hyatt for children, tennis court, and bicycle rental service • Complimentary Wi-Fi RESTAURANTS & BARS SERVICES & FACILITIES • Sha Tin 18 — serves Peking Duck and homestyle Chinese cuisine • 24-hour Room Service and concierge • Cafe • Babysitting service with prior arrangement • Pool Bar • Business centre and florist • Tin Tin Bar — presents cocktails with live music entertainment • Car parking facilities • Patisserie — serves homemade pastries 24 hours • Laundry services • Limousine MEETING & EVENT SPACE • Regency Club™ • Over 750 sq m of indoor and outdoor meeting and event space • A 430-sq m pillar-less ballroom with a 6.2-m ceiling and prefunction area • Three indoor Salons with natural daylight and connecting outdoor terrace • Nine meeting rooms on the Regency Club™ floors • Landscaped garden • Sha Tin 18 outdoor terrace LOCATION POINTS OF INTEREST Hong Kong • Situated adjacent to the University • Che Kung Temple Science Park MTR Station • Hong Kong Heritage Museum T O Sai Kung • -

Fudge Space Opera

Fudge Space Opera Version 0.3.0 2006-August-11 by Omar http://www.pobox.com/~rknop/Omar/fudge/spop Coprights, Trademarks, and Licences Fudge Space Opera is licenced under the Open Gaming Licence, version 1.0a; see Appendex A. Open Game License v 1.0 Copyright 2000, Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Fudge System Reference Document Copyright 2005, Grey Ghost Press, Inc.; Authors Steffan O’Sullivan, Ann Dupuis, with additional material by other authors as indicated within the text. Available for use under the Open Game License (see Appendix I) Fudge Space Opera Copyright 2005, Robert A. Knop Jr. Open Gaming Content Designation of Product Identity: Nothing herein is designated as Product Identity as outlined in section 1(e) of the Open Gaming License. Designation of Open Gaming Content: Everything herein is designated as Open Game Content as outlined in seciton 1(d) of the Open Gaming License. Fudge Space Opera -ii- Fudge Space Opera CONTENTS Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Why “Space Opera”? . ......... 1 1.2 WhatisHere ........................................ .......... 2 1.3 TheMostImportantThing .............................. ............ 2 2 Character Creation 3 2.1 GeneralNotes........................................ .......... 3 2.2 5-PointFudge....................................... ........... 3 3 Combat 7 3.1 Default Combat Options . .......... 7 3.2 Basic Armor and Weapon Mechanics . ........... 7 3.3 Cross-WeaponScaleAttacks. .............. 8 3.4 Suggested Weapon Scales . ........ 9 3.5 DamagetoPassengers ................................. ............ 9 3.6 GiantSpaceBeasts.................................... ........... 9 3.7 When To Use Fudge Scale .......................................... 10 3.8 RangedWeapons....................................... ......... 11 3.9 Explosions........................................ ............ 12 3.10 Missiles and Point Defense . .............. 12 -iii- Fudge Space Opera CONTENTS 3.11 Doing Too Many Things at Once . -

Living in the Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture

Living in The Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture Kacmaz Erk, G. (2016). Living in The Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture. The International Journal of New Media, Technology and the Arts, 13-25. Published in: The International Journal of New Media, Technology and the Arts Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2016 Gul Kacmaz Erk. Available under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The use of this material is permitted for non-commercial use provided the creator(s) and publisher receive attribution. No derivatives of this version are permitted. Official terms of this public license apply as indicated here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Pok Fu Lam Road Bus-Bus Interchange Scheme

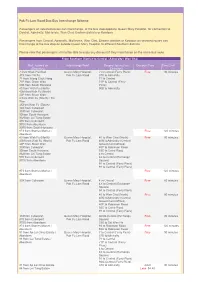

Pok Fu Lam Road Bus-Bus Interchange Scheme Passengers on selected routes can interchange, at the bus stop opposite Queen Mary Hospital, for connection to Central, Admiralty, Mid-levels, Wan Chai, Eastern districts or Kowloon. Passengers from Central, Admiralty, Mid-levels, Wan Chai, Eastern districts or Kowloon on selected routes can interchange at the bus stop on outside Queen Mary Hospital, to different Southern districts. Please note that passengers will not be able to enjoy any discount if they interchange on the same bus route. From Southern District to Central / Admiralty / Wan Chai First Journey on Interchange Point Second Journey on Discount Fare Time Limit (Direction) (Direction) 7 from Shek Pai Wan Queen Mary Hospital, 7 to Central (Ferry Piers) Free 90 minutes 37X from Chi Fu Pok Fu Lam Road 37X to Admiralty 71 from Wong Chuk Hang 71 to Central 71P from Sham Wan 71P to Central (Ferry 90B from South Horizons Piers) 40 from Wah Fu (North) 90B to Admiralty 40M fromWah Fu (North) 40P from Sham Wan 4 from Wah Fu (South) / Tin Wan 4Xfrom Wah Fu (South) 30X from Cyberport 33Xfrom Cyberport 93from South Horizons 93Afrom Lei Tung Estate 970 from Cyberport 970X from Aberdeen X970 from South Horizons 973 from Stanley Market / Free 120 minutes Aberdeen 40 from Wah Fu (North) Queen Mary Hospital, 40 to Wan Chai (North) Free 90 minutes 40M from Wah Fu (North) Pok Fu Lam Road 40M toAdmiralty (Central 40P from Sham Wan Government Offices) 33X from Cyberport 40P to Robinson Road 93from South Horizons 93C to Caine Road 93Afrom Lei Tung Estate -

CT Catalyst Air Purification Service Job Reference of Residence

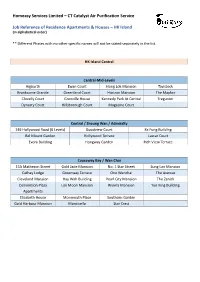

Homeasy Services Limited – CT Catalyst Air Purification Service Job Reference of Residence Apartments & Houses – HK Island (in alphabetical order) ** Different Phases with no other specific names will not be stated separately in the list. HK Island Central Central-Mid-Levels Aigburth Ewan Court Hong Lok Mansion Tavistock Branksome Grande Greenland Court Horizon Mansion The Mayfair Clovelly Court Grenville House Kennedy Park At Central Tregunter Dynasty Court Hillsborough Court Magazine Court Central / Sheung Wan / Admiralty 149 Hollywood Road (6 Levels) Goodview Court Ka Fung Building Bel Mount Garden Hollywood Terrace Lascar Court Evora Building Hongway Garden Rich View Terrace Causeway Bay / Wan Chai 15A Matheson Street Gold Jade Mansion No. 1 Star Street Sung Lan Mansion Cathay Lodge Greenway Terrave One Wanchai The Avenue Cleveland Mansion Hay Wah Building Pearl City Mansion The Zenith Convention Plaza Lok Moon Mansion Riviera Mansion Yue King Building Apartments Elizabeth House Monmouth Place Southorn Garden Gold Harbour Mansion Monticello Star Crest Happy Valley / East-Mid-Levels / Tai Hang 99 Wong Nai Chung Rd High Cliff Serenade Village Garden Beverly Hill Illumination Terrace Tai Hang Terrace Village Terrace Cavendish Heights Jardine's Lookout The Broadville Wah Fung Mansion Garden Mansion Celeste Court Malibu Garden The Legend Winfield Building Dragon Centre Nicholson Tower The Leighton Hill Wing On Lodge Flora Garden Richery Palace The Signature Wun Sha Tower Greenville Gardens Ronsdale Garden Tung Shan Terrace Hang Fung Building -

Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Journal.Finfar.Org

ISSN: 2342-2009 Fafnir vol 3, iss 4, pages 7–227–23 Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research journal.finfar.org Speculative Architectures in Comics Francesco-Alessio Ursini Abstract: The present article offers an analysis on how comics authors can employ architecture as a narrative trope, by focusing on the works of Tsutomu Nihei (Blame!, Sidonia no Kishi), and the duo of Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters (Le cités obscures). The article investigates how these authors use architectural tropes to create speculative fictions that develop renditions of cities as complex narrative environments, and “places” with a distinctive role and profile in stories. It is argued that these authors exploit the multimodal nature of comics and the potential of architecture to construct complex worlds and narrative structures. Keywords: architectural tropes, comics, narrative structure, speculative fiction, world-building, multimodality Biography and contact info: Francesco-Alessio Ursini is currently a lecturer in English linguistics and literature at Jönköping University. His works on comics include a special issue on Grant Morrison for the journal ImageTexT, and the forthcoming Visions of the Future in Comics (McFarland Press), both co-edited with Frank Bramlett and Adnan Mahmutović. Speculative fiction and comics have always been tightly connected across different cultural traditions. It has been argued that the “golden era” of manga (Japanese comics) in the 70’s and 80’s is based on the preponderance of works using science/speculative fiction settings (e.g. Akira, Ohsawa 9–26). Similarly, classic works in the “Latin” comic traditions (i.e. Latin American historietas, Italian fumetti, and French/Belgian bande desineés) have long represented an ideal nexus between the speculative fiction genre and the Comics medium, one example being El Eternauta (Page 46–50). -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Designing Cities, Planning for People

Designing cities, planning for people The guide books of Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon Minna Chudoba Tampere University of Technology School of Architecture [email protected] Abstract Urban theorists and critics write with an individual knowledge of the good urban life. Recently, writing about such life has boldly called for smart cities or even happy cities, stressing the importance of social connections and nearness to nature, or social and environmental capital. Although modernist planning has often been blamed for many current urban problems, the social and the environmental dimensions were not completely absent from earlier 20th century approaches to urban planning. Links can be found between the urban utopia of today and the mid-20th century ideas about good urban life. Changes in the ideas of what constitutes good urban life are investigated in this paper through two texts by two different 20th century planners: Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon. Both were taught by the Finnish planner Eliel Saarinen, and according to their teacher’s example, also wrote about their planning ideas. Meurman’s guide book for planners was published in 1947, and was a major influence on Finnish post-war planning. In Meurman’s case, the book answered a pedagogical need, as planners were trained to meet the demands of the structural changes of society and the needs of rapidly growing Finnish cities. Bacon, in a different context, stressed the importance of an urban design attitude even when planning the movement systems of a modern metropolis. Bacon’s book from 1967 was meant for both designers and city dwellers, exploring the dynamic nature of modern urbanity. -

Transhumanity's Fate

ECLIPSE PHASE: TRANSHUMANITY’S FATE The Fate Conversion Guide for Eclipse Phase RYAN JACK MACKLIN GRAHAM ECLIPSE PHASE: TRANSHUMANITY’S FATE Transhumanity’s Fate: ■ Brings technothriller espionage and horror in a world of upgraded humans to Fate Core. ■ Join Firewall, and defend transhumanity in the aftermath of near annihilation by arti cial intelligence. ■ Requires Fate Core to play. Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Transhumanity’s Fate is © 2016. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License. Fate™ is a trademark of Evil Hat Productions, LLC. The Powered by Fate logo is © Evil Hat Productions, LLC and is used with permission. eclipsephase.com TRANSHUMANITY'S FATE WRITING DEDICATION Jack Graham, Ryan Macklin The Posthumans dedicate this book to Jef Smith, our ADDITIONAL MATERIAL companion of many days & nights around the table. Jef was a tireless organizer in Chicago's science-fiction/ Rob Boyle, Caleb Stokes fantasy fandom, including the Think Galactic reading EDITING group and spin-off convention, Think Galacticon. In Rob Boyle, Jack Graham 2015, he co-published the Sisters of the Revolution: A GRAPHIC DESIGN Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology with PM Press. Adam Jury We will miss Jef's encouragement, wit, and bottomless COVER ART generosity. The person who lives large in the lives of their friends is not soon forgotten. Stephan Martiniere A portion of profits from Transhumanity's Fate will be INTERIOR ART donated to Jef's family. Rich Anderson, Nic Boone, Leanne Buckley, Anna Christenson, Daniel Clarke, Paul Davies, SPECIAL THANKS Alex Drummond, Danijel Firak, Nathan Geppert, Ryan thanks his wife, Lillian, for her support and Zachary Graves, Tariq Hassan, Josu Hernaiz, octomorph shenanigans, and blackcoat for being a font Jason Juta, Sergey Kondratovich, Ian Llanas, of feedback. -

Restaurant List

Restaurant List (updated 1 July 2020) Island Cafeholic Shop No.23, Ground Floor, Fu Tung Plaza, Fu Tung Estate, 6 Fu Tung Street, Tung Chung First Korean Restaurant Shop 102B, 1/F, Block A, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, Lantau Island Grand Kitchen Shop G10-101, G/F, JoysMark Shopping Centre, Mung Tung Estate, Tung Chung Gyu-Kaku Jinan-Bou Shop 706, 7th Floor, Citygate Outlets, Tung Chung HANNOSUKE (Tung Chung Citygate Outlets) Shop 101A, 1st Floor, Citygate, 18-20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Hung Fook Tong Shop No. 32, Ground Floor, Yat Tung Shopping Centre, Yat Tung Estate, 8 Yat Tung Street, Tung Chung Island Café Shop 105A, 1/F, Block A, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, Lantau Island Itamomo Shop No.2, G/F, Ying Tung Shopping Centre, Ying Tung Estate, 1 Ying Tung Road, Lantau Island, Tung Chung KYO WATAMI (Tung Chung Citygate Outlets) Shop B13, B1/F, Citygate Outlets, 20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island Moon Lok Chiu Chow Unit G22, G/F, Citygate, 20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island Mun Tung Café Shop 11, G/F, JoysMark Shopping Centre, Mun Tung Estate, Tung Chung Paradise Dynasty Shop 326A, 3/F, Citygate, 18-20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island Shanghai Breeze Shop 104A, 1/F, Block A, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, Lantau Island The Sixties Restaurant No. 34, Ground Floor, Commercial Centre 2, Yat Tung Estate, 8 Yat Tung Street, Tung Chung 十足風味 Shop N, G/F, Seaview Crescent, Tung Chung Waterfront Road, Tung Chung Kowloon City Yu Mai SHOP 6B G/F, Amazing World, 121 Baker Street, Site 1, Whampoa Garden, Hung Hom CAFÉ ABERDEEN Shop Nos.