Alien Megastructures: the Possibility of Extraterrestrial Life and the Rhetoric of Hope in the Anthropocene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Exoplanet Populations with NASA's Kepler Mission

SPECIAL FEATURE: PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE SPECIAL FEATURE: Exploring exoplanet populations with NASA’s Kepler Mission Natalie M. Batalha1 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, 94035 CA Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board June 3, 2014 (received for review January 15, 2014) The Kepler Mission is exploring the diversity of planets and planetary systems. Its legacy will be a catalog of discoveries sufficient for computing planet occurrence rates as a function of size, orbital period, star type, and insolation flux.The mission has made significant progress toward achieving that goal. Over 3,500 transiting exoplanets have been identified from the analysis of the first 3 y of data, 100 planets of which are in the habitable zone. The catalog has a high reliability rate (85–90% averaged over the period/radius plane), which is improving as follow-up observations continue. Dynamical (e.g., velocimetry and transit timing) and statistical methods have confirmed and characterized hundreds of planets over a large range of sizes and compositions for both single- and multiple-star systems. Population studies suggest that planets abound in our galaxy and that small planets are particularly frequent. Here, I report on the progress Kepler has made measuring the prevalence of exoplanets orbiting within one astronomical unit of their host stars in support of the National Aeronautics and Space Admin- istration’s long-term goal of finding habitable environments beyond the solar system. planet detection | transit photometry Searching for evidence of life beyond Earth is the Sun would produce an 84-ppm signal Translating Kepler’s discovery catalog into one of the primary goals of science agencies lasting ∼13 h. -

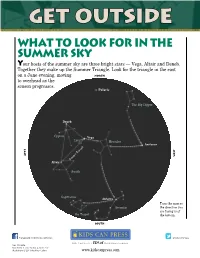

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your Hosts of the Summer Sky Are Three Bright Stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your hosts of the summer sky are three bright stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb. Together they make up the Summer Triangle. Look for the triangle in the east on a June evening, moving NORTH to overhead as the season progresses. Polaris The Big Dipper Deneb Cygnus Vega Lyra Hercules Arcturus EaST West Summer Triangle Altair Aquila Sagittarius Antares Turn the map so Scorpius the direction you are facing is at the Teapot the bottom. south facebook.com/KidsCanBooks @KidsCanPress GET OUTSIDE Text © 2013 Jane Drake & Ann Love Illustrations © 2013 Heather Collins www.kidscanpress.com Get Outside Vega The Keystone The brightest star in the Between Vega and Arcturus, Summer Triangle, Vega is look for four stars in a wedge or The summer bluish white. It is in the keystone shape. This is the body solstice constellation Lyra, the Harp. of Hercules, the Strongman. His feet are to the north and Every day from late Altair his arms to the south, making December to June, the The second-brightest star in his figure kneel Sun rises and sets a little the triangle, Altair is white. upside down farther north along the Altair is in the constellation in the sky. horizon. But about June Aquila, the Eagle. 21, the Sun seems to stop Keystone moving north. It rises in Deneb the northeast and sets in The dimmest star of the the northwest, seemingly Summer Triangle, Deneb would in the same spots for be the brightest if it were not so Hercules several days. -

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk Marcus Janni Pivato Many people seem to think that William Gibson invented The cyberpunk genre in 1984, but in fact the cyberpunk aesthetic was alive well before Neuromancer (1984). For example, in my opinion, Ridley Scott's 1982 movie, Blade Runner, captures the quintessence of the cyberpunk aesthetic: a juxtaposition of high technology with social decay as a troubling allegory of the relationship between humanity and machines ---in particular, artificially intelligent machines. I believe the aesthetic of the movie originates from Scott's own vision, because I didn't really find it in the Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968), upon which the movie is (very loosely) based. Neuromancer made a big splash not because it was the "first" cyberpunk novel, but rather, because it perfectly captured the Zeitgeist of anxiety and wonder that prevailed at the dawning of the present era of globalized economics, digital telecommunications, and exponential technological progress --things which we now take for granted but which, in the early 1980s were still new and frightening. For example, Gibson's novels exhibit a fascination with the "Japanification" of Western culture --then a major concern, but now a forgotten and laughable anxiety. This is also visible in the futuristic Los Angeles of Scott’s Blade Runner. Another early cyberpunk author is K.W. Jeter, whose imaginative and disturbing novels Dr. Adder (1984) and The Glass Hammer (1985) exemplify the dark underside of the genre. Some people also identify Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling as progenitors of cyberpunk. -

Summer Constellations

Night Sky 101: Summer Constellations The Summer Triangle Photo Credit: Smoky Mountain Astronomical Society The Summer Triangle is made up of three bright stars—Altair, in the constellation Aquila (the eagle), Deneb in Cygnus (the swan), and Vega Lyra (the lyre, or harp). Also called “The Northern Cross” or “The Backbone of the Milky Way,” Cygnus is a horizontal cross of five bright stars. In very dark skies, Cygnus helps viewers find the Milky Way. Albireo, the last star in Cygnus’s tail, is actually made up of two stars (a binary star). The separate stars can be seen with a 30 power telescope. The Ring Nebula, part of the constellation Lyra, can also be seen with this magnification. In Japanese mythology, Vega, the celestial princess and goddess, fell in love Altair. Her father did not approve of Altair, since he was a mortal. They were forbidden from seeing each other. The two lovers were placed in the sky, where they were separated by the Celestial River, repre- sented by the Milky Way. According to the legend, once a year, a bridge of magpies form, rep- resented by Cygnus, to reunite the lovers. Photo credit: Unknown Scorpius Also called Scorpio, Scorpius is one of the 12 Zodiac constellations, which are used in reading horoscopes. Scorpius represents those born during October 23 to November 21. Scorpio is easy to spot in the summer sky. It is made up of a long string bright stars, which are visible in most lights, especially Antares, because of its distinctly red color. Antares is about 850 times bigger than our sun and is a red giant. -

Fudge Space Opera

Fudge Space Opera Version 0.3.0 2006-August-11 by Omar http://www.pobox.com/~rknop/Omar/fudge/spop Coprights, Trademarks, and Licences Fudge Space Opera is licenced under the Open Gaming Licence, version 1.0a; see Appendex A. Open Game License v 1.0 Copyright 2000, Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Fudge System Reference Document Copyright 2005, Grey Ghost Press, Inc.; Authors Steffan O’Sullivan, Ann Dupuis, with additional material by other authors as indicated within the text. Available for use under the Open Game License (see Appendix I) Fudge Space Opera Copyright 2005, Robert A. Knop Jr. Open Gaming Content Designation of Product Identity: Nothing herein is designated as Product Identity as outlined in section 1(e) of the Open Gaming License. Designation of Open Gaming Content: Everything herein is designated as Open Game Content as outlined in seciton 1(d) of the Open Gaming License. Fudge Space Opera -ii- Fudge Space Opera CONTENTS Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Why “Space Opera”? . ......... 1 1.2 WhatisHere ........................................ .......... 2 1.3 TheMostImportantThing .............................. ............ 2 2 Character Creation 3 2.1 GeneralNotes........................................ .......... 3 2.2 5-PointFudge....................................... ........... 3 3 Combat 7 3.1 Default Combat Options . .......... 7 3.2 Basic Armor and Weapon Mechanics . ........... 7 3.3 Cross-WeaponScaleAttacks. .............. 8 3.4 Suggested Weapon Scales . ........ 9 3.5 DamagetoPassengers ................................. ............ 9 3.6 GiantSpaceBeasts.................................... ........... 9 3.7 When To Use Fudge Scale .......................................... 10 3.8 RangedWeapons....................................... ......... 11 3.9 Explosions........................................ ............ 12 3.10 Missiles and Point Defense . .............. 12 -iii- Fudge Space Opera CONTENTS 3.11 Doing Too Many Things at Once . -

New Idea for Dyson Sphere Proposed 30 March 2015, by Bob Yirka

New idea for Dyson sphere proposed 30 March 2015, by Bob Yirka that the massive amount of material needed to build such a sphere would be untenable, thus, a more likely scenario would be a civilization building a ring of energy capturing satellites which could be continually expanded. But the notion of the sphere persists and so some scientists continue to look for one, believing that if such a sphere were built, the process of capturing the energy from the interior sun would cause an unmistakable infrared signature, allowing us to notice its presence. But thus far, no such signatures have been found. That might be because we are alone in the universe, or, as Semiz and O?ur argue, it might be because we are looking at the wrong types of stars. They suggest that it would seem to make more sense for an advanced civilization to build their sphere around a white A Dyson Sphere with 1 AU radius in Sol system. Credit: dwarf, rather than a star that is in its main arXiv:1503.04376 [physics.pop-ph] sequence, such as our sun—not only would the sphere be smaller (they have even calculated an estimate for a sphere just one meter thick—1023 (Phys.org)—A pair of Turkish space scientists with kilograms of matter) but the gravity at its surface Bogazici University has proposed that researchers would be similar to their home planet (assuming it looking for the existence of Dyson spheres might were similar to ours). be looking at the wrong objects. ?brahim Semiz and Salim O?ur have written a paper and uploaded Unfortunately, if Semiz and O?ur are right, we may it to the preprint server arXiv, in which they suggest not be able to prove it for many years, as the that if an advanced civilization were to build a luminosity of a white dwarf is much less than other Dyson sphere, it would make the most sense to stars, making it extremely difficult to determine if build it around a white dwarf. -

Pyramid Volume 3 in These Issues (A Compilation of Tables of Contents and in This Issue Sections) Contents Name # Month Tools Of

Pyramid Volume 3 In These Issues (A compilation of tables of contents and In This Issue sections) Contents Name # Month Name # Month Tools of the Trade: Wizards 1 2008-11 Noir 42 2012-04 Looks Like a Job for… Superheroes 2 2008-12 Thaumatology III 43 2012-05 Venturing into the Badlands: Post- Alternate GURPS II 44 2012-06 3 2009-01 Apocalypse Monsters 45 2012-07 Magic on the Battlefield 4 2009-02 Weird Science 46 2012-08 Horror & Spies 5 2009-03 The Rogue's Life 47 2012-09 Space Colony Alpha 6 2009-04 Secret Magic 48 2012-10 Urban Fantasy [I] 7 2009-05 World-Hopping 49 2012-11 Cliffhangers 8 2009-06 Dungeon Fantasy II 50 2012-12 Space Opera 9 2009-07 Tech and Toys III 51 2013-01 Crime and Grime 10 2009-08 Low-Tech II 52 2013-02 Cinematic Locations 11 2009-09 Action [I] 53 2013-03 Tech and Toys [I] 12 2009-10 Social Engineering 54 2013-04 Thaumatology [I] 13 2009-11 Military Sci-Fi 55 2013-05 Martial Arts 14 2009-12 Prehistory 56 2013-06 Transhuman Space [I] 15 2010-01 Gunplay 57 2013-07 Historical Exploration 16 2010-02 Urban Fantasy II 58 2013-08 Modern Exploration 17 2010-03 Conspiracies 59 2013-09 Space Exploration 18 2010-04 Dungeon Fantasy III 60 2013-10 Tools of the Trade: Clerics 19 2010-05 Way of the Warrior 61 2013-11 Infinite Worlds [I] 20 2010-06 Transhuman Space II 62 2013-12 Cyberpunk 21 2010-07 Infinite Worlds II 63 2014-01 Banestorm 22 2010-08 Pirates and Swashbucklers 64 2014-02 Action Adventures 23 2010-09 Alternate GURPS III 65 2014-03 Bio-Tech 24 2010-10 The Laws of Magic 66 2014-04 Epic Magic 25 2010-11 Tools of the -

Constellation at Your Fingertips: Cygnus

The National Optical Astronomy Observatory’s Dark Skies and Energy Education Program Constellation at Your Fingertips: Cygnus (Cygnus version adapted from Constellation at Your Fingertips: Orion at www.globeatnight.org) Grades: 3rd - 8th grade Overview: Constellation at Your Fingertips introduces the novice constellation hunter to a method for spotting the main stars in the constellation, Cygnus, the swan. Students will make an outline of the constellation used to locate the stars in Cygnus and visualize its shape. This lesson will engage children and first-time night sky viewers in observations of the night sky. The lesson links history, Greek mythology, literature, and astronomy. Once the constellation is identified, it may be easy to find the summer triangle. The simplicity of Cygnus makes locating and observing it exciting for young learners. More on Cygnus is at the Great World Wide Star Count at http://www.starcount.org. Materials for another citizen-science star hunt, Globe at Night, are available at http://www.globeatnight.org. Purpose: Students will use the this activity to visualize the constellation of Cygnus. This will help them more easily participate in the Great World Wide Star Count citizen-science campaign. The campaign asks participants to match one of 7 different charts of Cygnus with what the participant sees toward Cygnus. Chart 1 has only a few stars. Chart 7 has many. What they will be recording for the campaign is the chart with the faintest star they see. In many cases, observations over years will build knowledge of how light pollution changes over time. Why is this important to astronomers? What causes the variation year to year? The focus is on light pollution and the options we have as consumers when purchasing outdoor lighting and shields. -

Astronomy 330 Classes Final Papers Final

Astronomy 330 Classes •! CHP allows $100 for informal get togethers. •! We are meeting Thursday to watch a movie and order some pizza. •! Still want Armageddon? Music: Space Race is Over – Billy Bragg Final Papers Final •! Final papers due on May 3rd. •! Take-home final –! At the beginning of class... •! Will email it out on the last class. •! You must turn final paper in with the graded •! Will consist of: rough draft. –! 2 large essays •! If you are happy with your rough draft grade as –! 2 short essays you final paper grade, then don’t worry about it. –! 5-8 short answers •! Due May 11th, hardcopy, by 5pm in my mailbox or office. Online ICES Outline •! What is the future for interstellar travel? •! ICES forms are available online. •! Fermi’s Paradox– Where are they? •! I appreciate you filling them out! –! In addition to campus honors thingy •! Please make sure to leave written comments. I find these comments the most useful, and typically that’s where I make the most changes to the course. Drake Equation Warp Drives Frank That’s 22,181 advanced civs!!! Drake •! Again, science fiction is influencing science. •! Due to great distance between the stars and the speed limit of c, sci-fi had to resort to “Warp Drive” that allows faster-than-light speeds. N = R* ! fp ! ne ! fl ! fi ! fc ! L •! Currently, this is impossible. # of # of •! It is speculation that requires a Star Fraction Fraction advanced Earthlike Fraction Fraction Lifetime of formation of stars that revolution in physics civilizations planets on which that evolve advanced rate with commun- we can per life arises intelligence civilizations –! It is science fiction! planets icate contact in system •! But, we have been surprised our Galaxy 6 before… today 15 0.65 1.3 x 0.1 0.125 0.175 .8 1x10 •! Unfortunately new physics usually = 0.13 intel./ comm./ yrs/ http://www.filmjerk.com/images/warp.gif stars/ systems/ life/ adds constraints not removes them. -

Location: NT-13 “Lamprey” Dyson Sphere Station (Incomplete), Edge of Terran Protectorate Shift Timestamp: 01:58 February, 30

Location: NT-13 “Lamprey” Dyson Sphere Station (Incomplete), Edge of Terran Protectorate Shift Timestamp: 01:58 February, 30, 2560 ‘The amazing part is,’ a voice in my head spoke up as I slipped through yet another set of maintenance shafts and corridors that looked exactly the same as the last ones I’d just ducked out of, ‘the whole power grid is still working.’ I nodded at that, and got back to work slapping wall mounted Security flashers onto the walls, outright using some Clown’s SUPER Glue to get the job done in as short a time as I could. It didn’t stop the robots from using the damn places, but at least it kept the more biological threats from trying their hands at rooting me out personally. Waking up in this life had been not good. … Azure ‘starlight’ seeps like syrup though cracks in the glass ceiling, through which a massive sapphire blue ‘star’ could easily be observed from the viens the station that were the maintenance halls. The floor shudders in time with the churning of machinery somewhere far beneath my feet. The air, if I were to pull off my hermetically sealed helmet off for a moment, has the strange tang of unknown chemicals and over-processed air that speaks of any space station, but the undertones of copper and something wholly unpleasant, something like rot and excrement and worse, are unique to this place. I stopped as a door opened in the distance and without even thinking I unholstered the gun from my chest sling. -

Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Journal.Finfar.Org

ISSN: 2342-2009 Fafnir vol 3, iss 4, pages 7–227–23 Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research journal.finfar.org Speculative Architectures in Comics Francesco-Alessio Ursini Abstract: The present article offers an analysis on how comics authors can employ architecture as a narrative trope, by focusing on the works of Tsutomu Nihei (Blame!, Sidonia no Kishi), and the duo of Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters (Le cités obscures). The article investigates how these authors use architectural tropes to create speculative fictions that develop renditions of cities as complex narrative environments, and “places” with a distinctive role and profile in stories. It is argued that these authors exploit the multimodal nature of comics and the potential of architecture to construct complex worlds and narrative structures. Keywords: architectural tropes, comics, narrative structure, speculative fiction, world-building, multimodality Biography and contact info: Francesco-Alessio Ursini is currently a lecturer in English linguistics and literature at Jönköping University. His works on comics include a special issue on Grant Morrison for the journal ImageTexT, and the forthcoming Visions of the Future in Comics (McFarland Press), both co-edited with Frank Bramlett and Adnan Mahmutović. Speculative fiction and comics have always been tightly connected across different cultural traditions. It has been argued that the “golden era” of manga (Japanese comics) in the 70’s and 80’s is based on the preponderance of works using science/speculative fiction settings (e.g. Akira, Ohsawa 9–26). Similarly, classic works in the “Latin” comic traditions (i.e. Latin American historietas, Italian fumetti, and French/Belgian bande desineés) have long represented an ideal nexus between the speculative fiction genre and the Comics medium, one example being El Eternauta (Page 46–50). -

The Kepler Characterization of the Variability Among A- and F-Type Stars I

A&A 534, A125 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117368 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics The Kepler characterization of the variability among A- and F-type stars I. General overview K. Uytterhoeven1,2,3,A.Moya4, A. Grigahcène5,J.A.Guzik6, J. Gutiérrez-Soto7,8,9, B. Smalley10, G. Handler11,12, L. A. Balona13,E.Niemczura14, L. Fox Machado15,S.Benatti16,17, E. Chapellier18, A. Tkachenko19, R. Szabó20, J. C. Suárez7,V.Ripepi21, J. Pascual7, P. Mathias22, S. Martín-Ruíz7,H.Lehmann23, J. Jackiewicz24,S.Hekker25,26, M. Gruberbauer27,11,R.A.García1, X. Dumusque5,28,D.Díaz-Fraile7,P.Bradley29, V. Antoci11,M.Roth2,B.Leroy8, S. J. Murphy30,P.DeCat31, J. Cuypers31, H. Kjeldsen32, J. Christensen-Dalsgaard32 ,M.Breger11,33, A. Pigulski14, L. L. Kiss20,34, M. Still35, S. E. Thompson36,andJ.VanCleve36 (Affiliations can be found after the references) Received 30 May 2011 / Accepted 29 June 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The Kepler spacecraft is providing time series of photometric data with micromagnitude precision for hundreds of A-F type stars. Aims. We present a first general characterization of the pulsational behaviour of A-F type stars as observed in the Kepler light curves of a sample of 750 candidate A-F type stars, and observationally investigate the relation between γ Doradus (γ Dor), δ Scuti (δ Sct), and hybrid stars. Methods. We compile a database of physical parameters for the sample stars from the literature and new ground-based observations. We analyse the Kepler light curve of each star and extract the pulsational frequencies using different frequency analysis methods.