Imagining Urban Futures Imagining Urbanfutures Cities in Science Fiction and What We Might Learn from Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dark Council of the Sith Empire

The Force Shall Free Me Dark Council of the Sith Empire “Peace is a lie; there is only passion. Through passion, I gain strength. Through strength, I gain power. Through power, I gain victory. Through victory, my chains are broken. The Force shall free me.” —The Sith Code Contents Letter from the Director ................................................................................................... 4 Mandate .......................................................................................................................... 5 Background ...................................................................................................................... 6 History .................................................................................................................. 6 Imperial Government Structure ............................................................................. 8 Key Planets to Know ............................................................................................. 8 Topics for Discussion ..................................................................................................... 10 Imperial Alliances ................................................................................................ 10 Sith and Non-Sith ................................................................................................ 12 Corruption .......................................................................................................... 14 Positions ....................................................................................................................... -

Touristic Disaster: Spectacle and Recovery in Post-Katrina New Orleans

Geoforum 86 (2017) 127–135 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geoforum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geoforum Touristic disaster: Spectacle and recovery in Post-Katrina New Orleans MARK Kevin Fox Gotham Tulane University, Newcomb Hall, Room 215, New Orleans, LA 70118, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keyword: This paper develops the concept touristic disaster as a heuristic device to examine the conflictual and contra- Spectacle disaster recovery tourism tours dictory aspects of showcasing disaster-devastated neighborhoods as tourist attractions. Touristic disaster refers to the application of tourism modes of staging, visualization, and discourse to reenchant the money making deterrents (stigma) of “destruction” and “ruin” and re-signify disaster to indicate “recovery” and “rebirth.” This paper uses empirical examples from New Orleans to examine the transition from “disaster tourism” to “recovery tourism” in tourism framings of post-Katrina rebuilding. The concept of touristic disaster views disaster-deva- stated neighborhoods as sites and arenas of contestation in which opposing groups and interests battle to control representations of urban space. The paper illustrates the motivations, processes, and paradoxical impacts of the commodification and global representation of “disaster” and “recovery” and provides insights into the ways in which people can use spectacle to contest marginalization. 1. Introduction the burgeoning growth of trauma-related and misery-laden attractions and their interconnection with different political, social, and cultural This paper investigates the conflictual and contradictory aspects of institutions and processes. showcasing disaster-devastated neighborhoods as tourist attractions, For decades, New Orleans has been one of the world’s most popular using a case study of the post-Katrina rebuilding process in New tourist and convention destinations, drawing approximately nine mil- Orleans. -

Star Wars: the Fascism Awakens Representation and Its Failure from the Weimar Republic to the Galactic Senate Chapman Rackaway University of West Georgia

STAR WARS: THE FASCISM AWAKENS 7 Star Wars: The Fascism Awakens Representation and its Failure from the Weimar Republic to the Galactic Senate Chapman Rackaway University of West Georgia Whether in science fiction or the establishment of an earthly democracy, constitutional design matters especially in the realm of representation. Democracies, no matter how strong or fragile, can fail under the influence of a poorly constructed representation plan. Two strong examples of representational failure emerge from the post-WWI Weimar Republic and the Galactic Republic’s Senate from the Star Wars saga. Both legislatures featured a combination of overbroad representation without minimum thresholds for minor parties to be elected to the legislature and multiple non- citizen constituencies represented in the body. As a result both the Weimar Reichstag and the Galactic Senate fell prey to a power-hungry manipulating zealot who used the divisions within their legislature to accumulate power. As a result, both democracies failed and became tyrannical governments under despotic leaders who eventually would be removed but only after wars of massive casualties. Representation matters, and both the Weimer legislature and Galactic Senate show the problems in designing democratic governments to fairly represent diverse populations while simultaneously limiting the ability of fringe groups to emerge. “The only thing necessary for the triumph of representative democracies. A poor evil is for good men to do nothing.” constitutional design can even lead to tyranny. – Edmund Burke (1848) Among the flaws most potentially damaging to a republic is a faulty representational “So this is how liberty dies … with structure. Republics can actually build too thunderous applause.” - Padme Amidala (Star much representation into their structures, the Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith, 2005) result of which is tyranny as a byproduct of democratic failure. -

Disaster Tourism the Role of Tourism in Post-Disaster Period of Great East Japan Earthquake

Disaster Tourism The Role of Tourism in Post-Disaster Period of Great East Japan Earthquake A Research Paper presented by: Noriyuki Nagai (JAPAN) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Specialization: Local Development Strategy (LDS) Members of the Examining Committee: Georgina Mercedes Gomez Erhard Berner The Hague, The Netherlands December 2012 ii Acknowledgement My deeply appreciation goes to my supervisor Dr Georgina Mercedes Gomez. Without her meticulous comments and consulting, there was no achievement. Special thanks also go to second reader Dr Erhard Berner whose insightful comments were an enormous help to me. I have greatly benefited from my discussants, Ika Kristiana Widyaningrum, Marco Antonio Bermudez Gonzalez and Alba Ximena Garcia Gutierrez, who provided helpful feedback. Discus- sion with Windawaty Pangaribuan and Oribie Sato; and proofreading of Grac- sious Ncube were also extremely beneficial. I would like to deeply appreciate interviewees in Tohoku, Japan. They provided my inspiration by beneficial comments. I truly hope for the earliest reconstruction of the affected area. I would also like to express my gratitude to my family and my wife Sayoko for their ungrudging support and encouragements. iii Contents List of Tables vi List of Figures vi List of Maps vi List of Appendices vi List of Acronyms vii Abstract viii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1-1 Background of Great East Japan Earthquake 1 1-2 How to Grasp Disaster Tourism in This Study 5 Chapter 2 -

American Rock with a European Twist: the Institutionalization of Rock’N’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20Th Century)❧

75 American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century)❧ Maria Kouvarou Universidad de Durham (Reino Unido). doi: dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit57.2015.05 Artículo recibido: 29 de septiembre de 2014 · Aprobado: 03 de febrero de 2015 · Modificado: 03 de marzo de 2015 Resumen: Este artículo evalúa las prácticas desarrolladas en Francia, Italia, Grecia y Alemania para adaptar la música rock’n’roll y acercarla más a sus propios estilos de música y normas societales, como se escucha en los primeros intentos de las respectivas industrias de música en crear sus propias versiones de él. El trabajo aborda estas prácticas, como instancias en los contextos francés, alemán, griego e italiano, de institucionalizar el rock’n’roll de acuerdo con sus propias posiciones frente a Estados Unidos, sus situaciones históricas y políticas y su pasado y presente cultural y musical. Palabras clave: Rock’n’roll, Europe, Guerra Fría, institucionalización, industria de música. American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century) Abstract: This paper assesses the practices developed in France, Italy, Greece, and Germany in order to accommodate rock’n’roll music and bring it closer to their own music styles and societal norms, as these are heard in the initial attempts of their music industries to create their own versions of it. The paper deals with these practices as instances of the French, German, Greek and Italian contexts to institutionalize rock’n’roll according to their positions regarding the USA, their historical and political situations, and their cultural and musical past and present. -

Alastair Reynolds

Alastair Reynolds Born in 1966, Alastair Reynolds trained as an astronomer before working for the European Space Agency on a variety of science projects. He started publishing science fiction in 1990, and has now produced more than sixty short stories, as well as fourteen solo novels. His recent books include the Poseidon's Children trilogy, a Doctor Who novel, and a collaboration with Stephen Baxter, entitled The Medusa Chronicles. He has won the BSFA, Sidewise, Seiun and European Science Fiction Society awards, and has been a finalist for the Hugo, Arthur C Clarke, Locus and Sturgeon awards. After a long residence in the Netherlands, he now lives with his wife in the Welsh valleys, not too far from his place of birth. Other than writing, he enjoys hillwalking, astronomy, birdwatching, guitars, and indulging his passion for steam trains. Agents Robert Kirby Associate Agent 0203 214 0800 Kate Walsh [email protected] 020 3214 0884 Publications Fiction Publication Notes Details United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Elysium Fire Featuring Inspector Dreyfus - one of Alastair Reynolds most popular characters - 2018 this is a fast paced SF crime story, combining a futuristic setting with a gripping Gollancz tale of technology, revolution and revenge. One citizen died a fortnight ago. Two a week ago. Four died yesterday . and unless the cause can be found - and stopped - within the next four months, everyone will be dead. For the Prefects, the hunt for a silent, hidden killer is on . -

Homo Sapiens Ethicus: Life, Death, Reincarnation, and Ascension

Homo Sapiens Ethicus Life, Death, Reincarnation and Ascension Part 3 of the Anthropology Series on the Hidden Origin of Homo Sapiens --daniel Introduction In order to understand how the created, Cro-Magnon man differs from other evolved life on our world, an investigation into the structure of life, itself, is a necessary prerequisite. Once the natural norm is defined, deviations from that norm can be investigated and consequences determined. This paper will cover two basic concepts, as energetic consequences: life and death, along with the evolution of these processes: reincarnation and ascension. Life, as a natural consequence of the postulates of the Reciprocal System, is covered in detail by Dewey Larson in his book, Beyond Space and Time.1 In hopes of defining the basic pattern of what causes natural death and what happens during, and after, the death of the physical body, the concepts of death, reincarnation and ascension are extrapolated from the core concepts of cultural mythology and theology, correlated to corresponding concepts in a framework of a universe of motion. This information can then be extrapolated to see where mankind, as a species, is heading. The pretext of this paper, based on the concepts proposed in Geochronology2 and New World Religion,3 is that Cro-Magnon man, from which modern man is a direct descendant, is a hybrid of the evolving life on the planet plus an “extra-terrestrial” or “divine” influence that was introduced by a species collectively referred to as the “SMs” that colonized the planet in ancient times, creating the Mu and Atlantean epochs.4 The progenitors of this hybrid species of man are commonly referred to as the Biblical Adam and Eve, so this hybrid approach is a mix between Darwinian views and theological ones—both are correct. -

SF Commentary 41-42

S F COMMENTARY 41/42 Brian De Palma (dir): GET TO KNOW YOUR RABBIT Bruce Gillespie: I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (86) . ■ (SFC 40) (96) Philip Dick (13, -18-19, 37, 45, 66, 80-82, 89- Bruce Gillespie (ed): S F COMMENTARY 30/31 (81, 91, 96-98) 95) Philip Dick: AUTOFAC (15) Dian Girard: EAT, DRINK AND BE MERRY (64) Philip Dick: FLOW MY TEARS THE POLICEMAN SAID Victor Gollancz Ltd (9-11, 73) (18-19) Paul Goodman (14). Gordon Dickson: THINGS WHICH ARE CAESAR'S (87) Giles Gordon (9) Thomas Disch (18, 54, 71, 81) John Gordon (75) Thomas Disch: EMANCIPATION (96) Betsey & David Gorman (95) Thomas Disch: THE RIGHT WAY TO FIGURE PLUMBING Granada Publishing (8) (7-8, 11) Gunter Grass: THE TIN DRUM (46) Thomas Disch: 334 (61-64, 71, 74) Thomas Gray: ELEGY WRITTEN IN A COUNTRY CHURCH Thomas Disch: THINGS LOST (87) YARD (19) Thomas Disch: A VACATION ON EARTH (8) Gene Hackman (86) Anatoliy Dneprov: THE ISLAND OF CRABS (15) Joe Haldeman: HERO (87) Stanley Donen (dir): SINGING IN THE RAIN (84- Joe Haldeman: POWER COMPLEX (87) 85) Knut Hamsun: MYSTERIES (83) John Donne (78) Carey Handfield (3, 8) Gardner Dozois: THE LAST DAY OF JULY (89) Lee Harding: FALLEN SPACEMAN (11) Gardner Dozois: A SPECIAL KIND OF MORNING (95- Lee Harding (ed): SPACE AGE NEWSLETTER (11) 96) Eric Harries-Harris (7) Eastercon 73 (47-54, 57-60, 82) Harry Harrison: BY THE FALLS (8) EAST LYNNE (80) Harry Harrison: MAKE ROOM! MAKE ROOM! (62) Heinz Edelman & George Dunning (dirs): YELLOW Harry Harrison: ONE STEP FROM EARTH (11) SUBMARINE (85) Harry Harrison & Brian Aldiss (eds): THE -

Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal

DANIELA CAPPELLO | 1 Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal Daniela Cappello Abstract: In this paper I look at four examples of Bengali SF (science fiction) comics by two great authors and illustrators of sequential art: Mayukh Chaudhuri (Yātrī, Smārak) and Narayan Debnath (Ḍrāgoner thābā, Ajānā deśe). Departing from a con- ventional understanding of SF as a fixed genre, I aim at showing that the SF comic is a ‘mode’ rather than a ‘genre’, building on a very fluid notion of boundaries between narrative styles, themes, and tropes formally associated with fixed genres. In these Bengali comics, it is especially the visual space of the comic that allows for blending and ‘contamination’ with other typical features drawn from adventure and detective fiction. Moreover, a dominant thematic thread that cross-cuts the narratives here examined are the tropes of the ‘other’ and the ‘unknown’, which are in fact central images of both adventure and SF: the exploration and encounter with ‘unknown’ (ajānā) worlds and ‘strange’ species (adbhut jāti) is mirrored in the usage of a lan- guage that expresses ‘otherness’ and strangeness. These examples show that the medium of the comic framing the SF story adds further possibilities of reading ‘genre hybridity’ as constitutive of the genre of SF as such. WHAT’S IN A COMIC? Before addressing SF comics in West Bengal, I will first look at some interna- tional definitions of comic to outline the main problematics that have been raised in the literature on this subject. In one of the first books introducing the world of comics to artists and academics, Will Eisner looks at the me- chanics of ‘sequential art’ (a term coined by Eisner himself) describing it as a dual ‘form of reading’ (Eisner 1985: 8): The format of the comic book presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretive skills. -

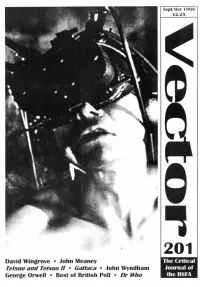

Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters the Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M

Sept/Oct 1998 £2.25 David Wingrove • John Meaney The Critical Tetsuo and Tetsuo II • Gattaca • John Wyndham Journal of George Orwell • Best of British Poll • Dr Who the BSFA Editorial Team Production and General Editing Tony Cullen - 16 Weaver's Way, Camden, London NW1 OXE Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters The Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M. Butler - 33 Brook View Drive, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5JN Email: [email protected] Contents Gary Dalkin - 5 Lydford Road, Bournemouth, 3 Editorial - The View from Hangar 23 Dorset, BH11 8SN by Andrew Butler Book Reviews 4 TO Paul Kincaid 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Letters to Vector Kent CT19 5AZ 5 Red Shift Email: [email protected] Corrections and Clarifications Printed by: 5 Afterthoughts: Reflections on having finished PDC Copyprint, 11 Jeffries Passage, Guildford, Chung Kuo Surrey GU1 4AP .by David Wingrove |The British Science Fiction Association Ltd. 6 Emergent Property An Interview with John Meaney by Maureen Kincaid Limited by guarantee. Company No. 921500. Registered Speller Address: 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Kent. CT19 5AZ 9 The Cohenstewart Discontinuity: Science in the | BSFA Membership Third Millennium by lohn Meaney UK Residents: £19 or £12 (unwaged) per year. 11 Man-Sized Monsters Please enquire for overseas rates by Colin Odell and Mitch Le Blanc 13 Gattaca: A scientific (queer) romance Renewals and New Members - Paul Billinger , 1 Long Row Close , Everdon, Daventry, Northants NN11 3BE by Andrew M Butler 15 -

SF COMMENTARY 101 February 2020 129 Pages

SF COMMENTARY 101 February 2020 129 pages JAMES ‘JOCKO’ ALLEN * GEOFF ALLSHORN * JENNY BLACKFORD * RUSSELL BLACKFORD * STEPHEN CAMPBELL * ELAINE COCHRANE * BRUCE GILLESPIE * DICK JENSSEN * EILEEN KERNAGHAN * DAVID RUSSELL * STEVE STILES * TIM TRAIN * CASEY JUNE WOLF * AND MANY MANY OTHERS Cover: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘Trumped!’. S F Commentary 101 February 2020 129 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 101, February 2020, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. DISTRIBUTION: Either portrait (print equivalent) or landscape .PDF file from eFanzines.com: http://efanzines.com or from my email address: [email protected]. FRONT COVER: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘Tumped!’. BACK COVER: Steve Stiles (classic reprint from cover of SF Commentary 91.) PHOTOGRAPHS: Elaine Cochrane (p. 7); Stephen Silvert (p. 11); Helena Binns (pp. 14, 16); Cat Sparks (p. 31); Leigh Edmonds (pp. 62, 63); Casey Wolf (p. 81); Richard Hyrckiewicz (p. 113); Werner Koopmann (pp. 127, 128). ILLUSTRATIONS: Steve Stiles (pp. 11, 12, 23); Stephen Campbell (pp. 51, 58); Chris Gregory (p. 78); David Russell (pp. 107, 128) Contents 30 RUSSELL BLACKFORD 41 TIM TRAIN SCIENCE FICTION AS A LENS INTO THE FUTURE MY PHILIP K. DICK BENDER 40 JENNY BLACKFORD 44 CASEY JUNE WOLF INTERVIEWS WRITING WORKSHOPS AT THE MUSLIM SCHOOL EILEEN KERNAGHAN 2 4 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY 20 BRUCE GILLESPIE FRIENDS The postal path to penury 4 BRUCE GILLESPIE The future is now! 51 LETTERS OF COMMENT 6 BRUCE GILLESPIE AND ELAINE COCHRANE Leanne Frahm :: Gerald Smith :: Stephen Camp- Farewell to the old ruler. Meet the new rulers. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction.