Fafnir Cover Page 1:2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906 B Culture and Society: Gothic and Horror Prerequisite(s): 1.0 credit in ENGL at the 1000 level or permission of the Department Tuesdays 6:05 – 8:55 pm 182 Unicentre Instructor: Aalya Ahmad, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Office: 1422 Dunton Tower Office Hours: please email me for an appointment Course Description: This course is an overview of Gothic and Horror fiction as literary genres or fictional modes that reflect and play with prevalent cultural fears and anxieties. Reading short stories that range from excerpts from the eighteenth-century Gothic novels to mid-century weird fiction to contemporary splatterpunk stories, students will also draw upon a wide range of literary and cultural studies theories that analyze and interpret Gothic and horror texts. By the end of this course, students should have a good grasp of the Gothic and Horror field, of its principal theoretical concepts, and be able to apply those concepts to texts more generally. Trigger Warning: This course examines graphic and potentially disturbing material. If you are triggered by anything you experience during this course and require assistance, please see me. Texts: All readings are available through the library or on ARES. Please note: where excerpts are indicated, students are also encouraged to read the entire text. Evaluation: 15% Journal (4 pages plus works cited list) due January 31 This assignment is designed to provide you with early feedback. In a short journal, please reflect on what you personally have found compelling about Gothic or horror fiction, including a short discussion of a favourite or memorable text(s). -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

THE FINNISH FANDOM All You Need to Know About It

THE FINNISH FANDOM all you need to know about it Pasi Karppanen What is this crazy Finnish fandom that seems to be bursting with energy, keeps organizing free cons, and now and then is even coaxed to organize the Worldcon? This article aims for an overview of the Finnish fandom. It is originally based on Ben Roimola’s “Short Look at Finnish Fandom” from 1995. A previous version of the article, updated by Pasi Karppanen and Shimo Suntila, was published in Cosmos Pen’s previous English special in 2003. The origins of Finnish fandom unoffi cial sf/f, anime and role playing ning and made Finnish fandom what clubs and zines. it is today. The fi rst signs of a phenomenon Finnish fandom has all the charac- Another thing that should be called fandom can be seen in Fin- teristics of fandom everywhere else. mentioned when speaking of Fin- land during 1950’s. However, it took There are societies, zines, awards, nish fandom is that there has never over two decades before fandom as cons, gatherings and all the other been that big a diff erence between we know it started to emerge. The things that together make up the science fi ction and fantasy. Every- reasons for this are various. In 1950’s thing that’s called fandom. On the body of course understands the dif- Finland was barely getting back on other hand, there are also couple of ferences between genres, but basi- its feet, economical resources were features in Finnish fandom that make cally the fans and writers of science limited and urbanisation was only it somewhat diff erent from other fi ction and fantasy, as far as Finnish beginning. -

Check All That Apply)

Form Version: February 2001 EFFECTIVE TERM: Fall 2003 PALOMAR COLLEGE COURSE OUTLINE OF RECORD FOR DEGREE CREDIT COURSE X Transfer Course X A.A. Degree applicable course (check all that apply) COURSE NUMBER AND TITLE: ENG 290 -- Comic Books As Literature UNIT VALUE: 3 MINIMUM NUMBER OF SEMESTER HOURS: 48 BASIC SKILLS REQUIREMENTS: Appropriate Language Skills ENTRANCE REQUIREMENTS PREREQUISITE: Eligibility for ENG 100 COREQUISITE: NONE RECOMMENDED PREPARATION: NONE SCOPE OF COURSE: An analysis of the comic book in terms of its unique poetics (the complicated interplay of word and image); the themes that are suggested in various works; the history and development of the form and its subgenres; and the expectations of comic book readers. Examines the influence of history, culture, and economics on comic book artists and writers. Explores definitions of “literature,” how these definitions apply to comic books, and the tensions that arise from such applications. SPECIFIC COURSE OBJECTIVES: The successful student will: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the unique poetics of comic books and how that poetics differs from other media, such as prose and film. 2. Analyze representative works in order to interpret their styles, themes, and audience expectations, and compare and contrast the styles, themes, and audience expectations of works by several different artists/writers. 3. Demonstrate knowledge about the history and development of the comic book as an artistic, narrative form. 4. Demonstrate knowledge about the characteristics of and developments in the various subgenres of comic books (e.g., war comics, horror comics, superhero comics, underground comics). 5. Identify important historical, cultural, and economic factors that have influenced comic book artists/writers. -

Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal

DANIELA CAPPELLO | 1 Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal Daniela Cappello Abstract: In this paper I look at four examples of Bengali SF (science fiction) comics by two great authors and illustrators of sequential art: Mayukh Chaudhuri (Yātrī, Smārak) and Narayan Debnath (Ḍrāgoner thābā, Ajānā deśe). Departing from a con- ventional understanding of SF as a fixed genre, I aim at showing that the SF comic is a ‘mode’ rather than a ‘genre’, building on a very fluid notion of boundaries between narrative styles, themes, and tropes formally associated with fixed genres. In these Bengali comics, it is especially the visual space of the comic that allows for blending and ‘contamination’ with other typical features drawn from adventure and detective fiction. Moreover, a dominant thematic thread that cross-cuts the narratives here examined are the tropes of the ‘other’ and the ‘unknown’, which are in fact central images of both adventure and SF: the exploration and encounter with ‘unknown’ (ajānā) worlds and ‘strange’ species (adbhut jāti) is mirrored in the usage of a lan- guage that expresses ‘otherness’ and strangeness. These examples show that the medium of the comic framing the SF story adds further possibilities of reading ‘genre hybridity’ as constitutive of the genre of SF as such. WHAT’S IN A COMIC? Before addressing SF comics in West Bengal, I will first look at some interna- tional definitions of comic to outline the main problematics that have been raised in the literature on this subject. In one of the first books introducing the world of comics to artists and academics, Will Eisner looks at the me- chanics of ‘sequential art’ (a term coined by Eisner himself) describing it as a dual ‘form of reading’ (Eisner 1985: 8): The format of the comic book presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretive skills. -

Art Spiegelman's Experiments in Pornography

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Art Spiegelman’s ‘Little Signs of Passion’ and the Emergence of Hard-Core Pornographic Feature Film AUTHORS Williams, PG JOURNAL Textual Practice DEPOSITED IN ORE 20 August 2018 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/33778 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Art Spiegelman’s ‘Little Signs of Passion’ and the emergence of hard-core pornographic feature film Paul Williams In 1973 Bob Schneider and the underground comix1 creator Art Spiegelman compiled Whole Grains: A Book of Quotations. One of the aphorisms included in their book came from D. H. Lawrence: ‘What is pornography to one man is the laughter of genius to another’.2 Taking a cue from this I will explore how Spiegelman’s comic ‘Little Signs of Passion’ (1974) turned sexually explicit subject matter into an exuberant narratological experiment. This three-page text begins by juxtaposing romance comics against hard-core pornography,3 the former appearing predictable and artificial, the latter raw and shocking, but this initial contrast breaks down; rebutting the defenders of pornography who argued that it represented a welcome liberation from repressive sexual morality, ‘Little Signs of Passion’ reveals how hard-core filmmakers turned fellatio and the so-called money shot (a close-up of visible penile ejaculation) into standardised narrative conventions yielding lucrative returns at the box office. -

Joe Rosochacki - Poems

Poetry Series Joe Rosochacki - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joe Rosochacki(April 8,1954) Although I am a musician, (BM in guitar performance & MA in Music Theory- literature, Eastern Michigan University) guitarist-composer- teacher, I often dabbled with lyrics and continued with my observations that I had written before in the mid-eighties My Observations are mostly prose with poetic lilt. Observations include historical facts, conjecture, objective and subjective views and things that perplex me in life. The Observations that I write are more or less Op. Ed. in format. Although I grew up in Hamtramck, Michigan in the US my current residence is now in Cumby, Texas and I am happily married to my wife, Judy. I invite to listen to my guitar works www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Dead Hand You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, Know when to walk away and know when to run. You never count your money when you're sittin at the table. There'll be time enough for countin' when the dealins' done. David Reese too young to fold, David Reese a popular jack of all trades when it came to poker, The bluffing, the betting, the skill that he played poker, - was his ace of his sleeve. He played poker without deuces wild, not needing Jokers. To bad his lungs were not flushed out for him to breathe, Was is the casino smoke? Or was it his lifestyle in general? But whatever the circumstance was, he cashed out to soon, he had gone to see his maker, He was relatively young far from being too old. -

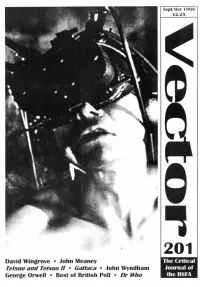

Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters the Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M

Sept/Oct 1998 £2.25 David Wingrove • John Meaney The Critical Tetsuo and Tetsuo II • Gattaca • John Wyndham Journal of George Orwell • Best of British Poll • Dr Who the BSFA Editorial Team Production and General Editing Tony Cullen - 16 Weaver's Way, Camden, London NW1 OXE Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters The Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M. Butler - 33 Brook View Drive, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5JN Email: [email protected] Contents Gary Dalkin - 5 Lydford Road, Bournemouth, 3 Editorial - The View from Hangar 23 Dorset, BH11 8SN by Andrew Butler Book Reviews 4 TO Paul Kincaid 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Letters to Vector Kent CT19 5AZ 5 Red Shift Email: [email protected] Corrections and Clarifications Printed by: 5 Afterthoughts: Reflections on having finished PDC Copyprint, 11 Jeffries Passage, Guildford, Chung Kuo Surrey GU1 4AP .by David Wingrove |The British Science Fiction Association Ltd. 6 Emergent Property An Interview with John Meaney by Maureen Kincaid Limited by guarantee. Company No. 921500. Registered Speller Address: 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Kent. CT19 5AZ 9 The Cohenstewart Discontinuity: Science in the | BSFA Membership Third Millennium by lohn Meaney UK Residents: £19 or £12 (unwaged) per year. 11 Man-Sized Monsters Please enquire for overseas rates by Colin Odell and Mitch Le Blanc 13 Gattaca: A scientific (queer) romance Renewals and New Members - Paul Billinger , 1 Long Row Close , Everdon, Daventry, Northants NN11 3BE by Andrew M Butler 15 -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

BERNARD BAILY Vol

Roy Thomas’ Star-Bedecked $ Comics Fanzine JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT 8.95 YOU KNEW EVERYTHING THERE In the USA WAS TO KNOW ABOUT THE No.109 May JUSTICE 2012 SOCIETY ofAMERICA!™ 5 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 Art © DC Comics; Justice Society of America TM & © 2012 DC Comics. Plus: SPECTRE & HOUR-MAN 6 2 8 Co-Creator 1 BERNARD BAILY Vol. 3, No. 109 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck AT LAST! Comic Crypt Editor ALL IN Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll COLOR FOR $8.95! Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artist Contents George Pérez Writer/Editorial: An All-Star Cast—Of Mind. 2 Cover Colorist Bernard Baily: The Early Years . 3 Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Ken Quattro examines the career of the artist who co-created The Spectre and Hour-Man. “Fairytales Can Come True…” . 17 Rob Allen Roger Hill The Roy Thomas/Michael Bair 1980s JSA retro-series that didn’t quite happen! Heidi Amash Allan Holtz Dave Armstrong Carmine Infantino What If All-Star Comics Had Sported A Variant Line-up? . 25 Amy Baily William B. Jones, Jr. Eugene Baily Jim Kealy Hurricane Heeran imagines different 1940s JSA memberships—and rivals! Jill Baily Kirk Kimball “Will” Power. 33 Regina Baily Paul Levitz Stephen Baily Mark Lewis Pages from that legendary “lost” Golden Age JSA epic—in color for the first time ever! Michael Bair Bob Lubbers “I Absolutely Love What I’m Doing!” . -

BARKER, Clive

BARKER, Clive Geboren: Liverpool, Engeland, 1952 Woont met zijn partner, fotograaf David Armstrong en hun dochter Nicole in Californië, USA (foto: David Armstrong/Tangled Web) detective: Harry D’Amour , privé-detective, New York Harry D’Amour/The Book of Art: The Great and Secret Show: De Grote Geheime Show: The First Book of the Art 1989 Het eerste boek van de kunst 1990 Luitingh~Sijthoff Everville: The Second Book of the Art 1994 Everville 1995 Luitingh~Sijthoff korte verhalen: “The Last Illusion” in: Clive Barker’s Books of Blood, vol 6 1985 “Lost Souls” in: Time Out 1985 Verloren zielen 1988 Luitingh Imajica: Imajica 1991 Imagica 1992 Luitingh~Sijthoff Imajica: The Fifth Dominion 1995 Imajica: The Reconciliation 1995 Abarat: 1. Abarat. The First Book of Hours 2002 1. Abarat 2004 Luitingh~Sijthoff 2. Days of Magic, Nights of War 2004 2. Dagen vol magie, nachten vol strijd 2004 Luitingh 3. Absolute Midnight 2007 andere crimetitels: The Damnation Game 1985 Duivelsspel 1989 Luitingh~Sijthoff Weaveworld 1987 Weefwereld 1988 Luitingh Cabal: The Night Breed 1988 Kabal 1989 Luitingh The Art 1989 De kunst 1995 Luitingh~Sijthoff Hellraiser eerder verschenen in Comic Books 1989-94 The Thief of Always (jun) 1992 De dief van altijd 1995 Luitingh~Sijthoff Sacrament 1996 Sacrament 1997 Luitingh~Sijthoff Galilee 1998 Galilee 1999 Luitingh~Sijthoff Cold Heart Canyon 2001 Coldheart Canyon 2002 Luitingh~Sijthoff Mister B. Gone 2007 Meneer W.E.G. Wezen 2008 Luitingh Fantasy korte verhalen: Books of Blood (Vol I & II) # 1984 Tunnel van de dood en andere