{FREE} Breton Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Correspondence Between the Rev. John Heckewelder, of Bethlehem

m ! 3Mm (forfrr ^IWfon Ctlmun iGtiTuiit^ntOcrstttt 1 n r . if «a • .. .\ > P * I 1 \ . / f \ i -^Jc v% • ho L TRANSACTIONS OF THE HISTORICAL % LITERARY COMMITTEE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY, HELD AT PHILADELPHIA, FOR PROMOTING USEFUL KNOWLEDGE. VOL. I. domestica vobis ; Invenies illic et facta legendus avus.—Ovid. Sxpe tibi pater est, ssepe PHILADELPHIA: Small, Printed and Published by Abraham No. 112, Chesnut Street, 1819. m y ^^1 oSlft, L I i No. II. CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN THE REV. JOHN HECKEWELDER, OF BETHLEHEM, AND PETER S. DUPONCEAU, ESQ. CORRESPONDING SECRETARY OF THE HISTORICAL AND LITERARY COMMITTEE OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCffiTY, RESPECTING The Languages of the American Indians, " ll, II I' ' ! i CONTENTS OF NO. II. INTRODUCTION Page 355 357 Letter I.—Mr. Duponceau to Mr. Heckewelder, 9th January, 1806, 358 II—Dr. C. Wistar to Mr. Heckewelder, (same date) 360 1X1.—Mr. Heckewelder to Dr. Wistar, 24th March, 363 IV.—The Same to the Same, 3d April, 364 V.—Mr. Duponceau to Dr. Wistar, 14th May, 364 VI.—Dr. Wistar to Mr Heckewelder, 21st May, 366 VII.— Mr. Heckewelder to Mr. Duponceau, 27th May, VIII.—Mr. Duponceau to Mr. Heckewelder, 10th June, 369 375 IX.—The Same to the Same, 13th June, 377 X.—Mr. Heckewelder to Mr. Duponceau, 20th June, 382 XI.—The Same to the Same, 24th June, XII.—Mr Duponceau to Mr. Heckewelder, 13th July, 383 387 XIII.—The Same to the Same, 18th July, 22d July, . XIV.—Mr Heckewelder to Mr. Duponceau, 392 • XV.—The Same to the Same, 24th July, 31st July, 396 . XVI.—Mr. -

Ф-Feature Agreement: the Distribution of the Breton Bare and Prepositional Infinitives with the Preposition Da

Ф-feature agreement: the distribution of the Breton bare and prepositional infinitives with the preposition da MÉLANIE JOUITTEAU Abstract This article investigates the hypothesis that infinitive clauses in Breton are case-filtered. This hypothesis makes a straightforward prediction for the distribution of infinitive clauses: bare infinitives appear in positions where direct case is available to them; prepositional infinitives appear as a last resort, in positions where no case is available. In these environments, da, homophonous with a preposition, appears at the left-edge of the infinitive clause. I propose that da realizes inherent case. I show that once the paradigms of semantically motivated preposition insertion are set apart, the hypothesis shows correct for control and ECM structures, with both intervening subjects and objects, purpose clauses and their alternation paradigms, including some preposition tripling paradigms. Larger infinitive structures in narrative matrix infinitives and concessive clauses are not case- -filtered. This makes Breton similar to English, where only perception and causative structures are case-filtered, whereas other infinitive structures are not (Hornstein, Martins & Nunes 2008). Keywords: Prepositional infinitives, bare infinitives, inherent case, Celtic, last resort 1. Introduction The literature reports a strange paradigm of preposition insertion at the left- -edge of small-clauses in Breton, as in the purpose clause in (1). Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 11-1 (2012), 99-119 ISSN 1645-4537 100 Mélanie Jouitteau (1) Reit din ur bluenn vat da Yann da skrivañ aesoc’h a se. give to-me a quill good P Yann to write easily-more of it ‘Give me a good quill, for Yann to write more easily.’ Treger, Tallerman (1997), cited from Stephens (1990) Hendrick (1988) proposes that the higher da in (1) is a prepositional complementizer. -

Negation, Referentiality and Boundedness In

WECATfON, REFERENTLALm ANT) BOUNDEDNESS flV BRETON A CASE STUDY Dl MARKEDNESS ANI) ASYMMETRY Nathalie Simone rMarie Schapansky B.A. (French), %=on Fraser University 1990 M.A. (Linguistics), Simon Fraser university 1992 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIEiEMEN'I'S FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Linguistics @Nathalie Simone Marie Schapansky, 1996 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY November 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. BibiiotMque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliogra~hicServices Branch des services bibiiographiques Your hie Vorre rbference Our hle Notre r6Orence The author has granted an k'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable nsn-exclusive f icence irtct5vocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of perrnettant a la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, prgttor, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque rnaniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes interessees. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial these. Ni la these ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent &re imprimes ou his/her permission. -

Practices and Perceptions Around Breton As a Regional Language Of

New speaker language and identity: Practices and perceptions around Breton as a regional language of France Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Merryn Davies-Deacon B.A., M.A. February, 2020 School of Arts, English, and Languages Abstract This thesis focuses on the lexicon of Breton, a minoritised Celtic language traditionally spoken in western Brittany, in north-west France. For the past thirty years, much work on Breton has highlighted various apparent differences between two groups of speak- ers, roughly equivalent to the categories of new speakers and traditional speakers that have emerged more universally in more recent work. In the case of Breton, the concep- tualisation of these two categories entails a number of linguistic and non-linguistic ste- reotypes; one of the most salient concerns the lexicon, specifically issues around newer and more technical vocabulary. Traditional speakers are said to use French borrowings in such cases, influenced by the dominance of French in the wider environment, while new speakers are portrayed as eschewing these in favour of a “purer” form of Breton, which instead more closely reflects the language’s membership of the Celtic family, in- volving in particular the use of neologisms based on existing Breton roots. This thesis interrogates this stereotypical divide by focusing on the language of new speakers in particular, examining language used in the media, a context where new speakers are likely to be highly represented. The bulk of the analysis presented in this work refers to a corpus of Breton gathered from media sources, comprising radio broadcasts, social media and print publications. -

Minority Language Survival: Code-Mixing in Welsh

Minority Language Survival: Code-mixing in Welsh Margaret Deuchar University of Wales, Bangor 1. Introduction The aim of this paper is to report on the results of some preliminary analysis of Welsh-English code-mixing data, in order to determine which structural pattern of code-mixing is predominant. This is the first step of a more wide-ranging analysis which will deal with a larger amount of data and will contribute to the issue of which linguistic and extralinguistic factors may influence the occurrence of one type of code-mixing rather than another. A secondary aim of this study is to test the viability of a typological approach by developing a methodological tool to identify the dominant pattern of code- mixing based on diagnostic features The term code-mixing is used following Muysken (2000:1) to refer “to all cases where lexical items and grammatical features from two languages appear in one sentence” and the focus of interest will be on “intrasentential mixing” or mixing where elements from both languages appear in the same sentence. Many authors use the term code-switching to refer to the same phenomenon. 2. Previous research 2.1 On code-mixing in general Previous research on code-mixing has followed three main trends: (a) the search for universal constraints, typified by the seminal work of Poplack (1980); (b) the assumption of asymmetry, initiated by Joshi (1985) and developed by Myers-Scotton (1993) and (c) the typological approach, advocated by Muysken (2000). Muysken suggests that instead of one code-mixing model serving for all language pairs, there are three main types of code-mixing: insertional, alternational and congruent lexicalization. -

ON the ROLE of the COPULAR PARTICLE: EVIDENCE from WELSH Celtic Linguistics Conference 7, Rennes, June 22-23, 2012

1 Ora Matushansky, UiL OTS/Utrecht University/CNRS/Université Paris-8 email: O.M.Mаtushа[email protected] homepage: http://www.let.uu.nl/~Ora.Matushansky/personal/ ON THE ROLE OF THE COPULAR PARTICLE: EVIDENCE FROM WELSH Celtic Linguistics Conference 7, Rennes, June 22-23, 2012 1. INTRODUCTION: THE SYNTACTIC THEORY OF MEDIATED PREDICATION Bowers 1993, 2001: all predication must be mediated by a functional head Pred0 (originally, Pr°). The small clause is a projection of this head (PredP). (1) VP V0 PredP = small clause consider DP Pred Marie Pred0 AP ø proud of her work Empirical evidence: predicate case-marking (Bailyn and Rubin 1991, Bailyn and Citko 1999, Bailyn 2001, 2002) and copular particles, as well as some finer details of small-clause syntax The semantic function of Pred is to create a predicate out of an entity-correlate (or some such construct): APs, NPs and PPs are hypothesized to not denote predicates, and therefore require conversion into predicates (Bowers 1993 citing Chierchia 1985, Chierchia and Turner 1988) NB: Both Bowers 1993, 2001 and den Dikken 2006 take the extreme position, though for different reasons: verbal predication must also be mediated by a functional head. We will not address this complication here. Bowers 1993, Baker 2003: the Welsh particle yn is an overt realization of Pred° 2. WELSH COPULAR PARTICLE Initial confirmation: yn clearly appears in small clauses Primary predication: (2) a. Mae Siôn *(yn) ddedwydd. Rouveret 1996:128 is Siôn PRT happy Siôn is happy. b. Y mae Siôn *(yn) feddyg. PRT is Siôn PRT doctor Siôn is a doctor. -

Chapter 17 Culture and Language

Chapter 17 Culture and Language Each language sets certain limits to the spirit of those who speak it; it assumes a certain direction and, by doing so, excludes many others. — Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) Learning a language represents training in the delusions of that language. — Frank Herbert, Whipping Star There are about 6000 languages in the world, not counting the ones that have existed in the past but are dead now. I've said that before, haven't i? There are 6000 different languages in the world, and one of the ways in which they differ is in how they correlate with reality. Reality is represen- ted in different languages in different ways. But now, think about this: How do we talk about reality? How do we think about reality? Obviously, we can't talk about reality without using lan- guage, some language or other. So the way a given language represents reality obviously affects how we talk about reality — if we're using that particular language. But let's bear in mind an important theme underlying this semester's work: Language is a social phenomenon. In some sense, a language belongs to the community of people that use it. If the fact that i am speaking English affects the way i talk and think about reality, then presumably it should have roughly the same affect on everybody else who uses English — the entire English- speaking (or at least English-using) community. And, given the differences between English and the Chinese languages, that may be a little bit different from the way a Chinese-speaking commu- nity like yours is accustomed to representing reality. -

Rule-Based Breton to French Machine Translation

[EAMT May 2010 St Raphael, France] Rule-based Breton to French machine translation Francis M. Tyers Departament de Llenguatges i Sistemes Informatics` Universitat d’Alacant E-03070 Alacant [email protected] Abstract Speakers of minority or regional languages typ- ically differ from the majority in being bilingual, This paper describes a rule-based machine speaking both their language, and the language translation system from Breton to French of the majority. In contrast, a majority language intended for producing gisting translations. speaker does not usually speak the minority or re- The paper presents a summary of the ongo- gional language. This has some implications for ing development of the system, along with the requirements society will put on machine trans- an evaluation of two versions, and some lation systems. reflection on the use of MT systems for Applications of machine translation system can lesser-resourced or minority languages. be divided in two main groups: assimilation, that is, to enable a user to understand what the text is 1 Introduction about; and dissemination, that is, to help in the task of translating a text to be published. The require- This paper describes the development of a “gist- ments of either group of applications is different. ing” machine translation system between Breton Assimilation may be possible even when the and French.1 The first section will give a general text is far from being grammatically correct; how- overview of the two languages in question and de- ever, for dissemination, the effort needed to correct scribe the aims for the current system. The subse- (post-edit) the text must not be so high that it is quent sections will describe some of the develop- preferable to translate it manually from scratch. -

Orthographies and Ideologies in Revived Cornish

Orthographies and ideologies in revived Cornish Merryn Sophie Davies-Deacon MA by research University of York Language and Linguistic Science September 2016 Abstract While orthography development involves detailed linguistic work, it is particularly subject to non-linguistic influences, including beliefs relating to group identity, as well as political context and the level of available state support. This thesis investigates the development of orthographies for Cornish, a minority language spoken in the UK. Cornish is a revived language: while it is now used by several hundred people, it underwent language death in the early modern era, with the result that no one orthography ever came to take precedence naturally. During the revival, a number of orthographies have been created, following different principles. This thesis begins by giving an account of the development of these different orthographies, focusing on the context in which this took place and how contextual factors affected their implementation and reception. Following this, the situation of Cornish is compared to that of Breton, its closest linguistic neighbour and a minority language which has experienced revitalisation, and the creation of multiple orthographies, over the same period. Factors affecting both languages are identified, reinforcing the importance of certain contextual influences. After this, materials related to both languages, including language policy, examinations, and learning resources, are investigated in order to determine the extent to which they acknowledge the multiplicity of orthographies in Cornish and Breton. The results of this investigation indicate that while a certain orthography appears to have been established as a standard in the case of Breton, this cannot be said for Cornish, despite significant amounts of language planning work in this domain in recent years. -

1 the Celts and Their Languages

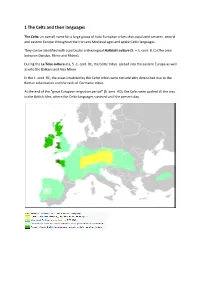

1 The Celts and their languages The Celts: an overall name for a large group of Indo-European tribes that populated western, central and eastern Europe throughout the Iron and Medieval ages and spoke Celtic languages. They can be identified with a particular archeological Hallstatt culture (8. – 5. cent. B. C) (The area between Danube, Rhine and Rhône). During the La Tène culture era, 5.-1. cent. BC, the Celtic tribes spread into the eastern Europe as well as into the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the 1. cent. BC, the areas inhabited by the Celtic tribes were considerably diminished due to the Roman colonization and the raids of Germanic tribes. At the end of the “great European migration period” (6. cent. AD), the Celts were pushed all the way to the British Isles, where the Celtic languages survived until the present day. The oldest roots of the Celtic languages can be traced back into the first half of the 2. millennium BC. This rich ethnic group was probably created by a few pre-existing cultures merging together. The Celts shared a common language, culture and beliefs, but they never created a unified state. The first time the Celts were mentioned in the classical Greek text was in the 6th cent. BC, in the text called Ora maritima written by Hecateo of Mileto (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC). He placed the main Celtic settlements into the area of the spring of the river Danube and further west. The ethnic name Kelto… (Herodotus), Kšltai (Strabo), Celtae (Caesar), KeltŇj (Callimachus), is usually etymologically explainedwith the ie. -

Practices and Perceptions Around Breton As a Regional Language of France

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY New speaker language and identity: Practices and perceptions around Breton as a regional language of France Davies-Deacon, Merryn Award date: 2020 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. -

The Preverbal Position in Breton and Relational Visibility

THE PREVERBAL POSITION IN BRETON AND RELATIONAL VISIBILITY Nathalie Simone Marie Schapansky B .A. (French), Simon Fraser University, 1990 THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (LINGUISTICS) in the Department of Linguistics @ Nathalie Simone Marie Schapansky, 1992 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY February 1992 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author Approval NAME: Nathalie Simone Marie Schapansky DEGREE: Master Degree of Arts (Linguistics) TITLE OF THESIS: The Preverbal Position in Breton and Relational Visibility EXAMINING COMMITIEE: Chair: Dr. N. Hedberg Assistant Professor, Linguistics and Cognitive Science V Dr. D.B. Gerdts Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. E.W. Roberts Prdessor Dr. P.L. wragner Professor Emeritus, Geography External Examiner DATE APPROVED: Fp&- ,, \, 9r( 2 -3 , i i PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay he- ?cr v~-rhulTo51 b1011 in arcton ancl Author: .