Social Structure of Accumulation in Turkey (1963 – 2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue:March 2020 #1

CATALOGUE: MARCH 2020 #1 - A large collection of over 500 mostly pulp novels and magazines in Ottoman language, influenced by the Western roaring 20s, especially by the Silent Movies. - Books on the early 20th Century Magic and Supernatural from the Islamic World. - A series of books by the most prominent representative of Turkish avantgarde Nâzım Hikmet. - Turkish Mid Century book and poster design - Slovenian books by contemporary artists - And Much More… www.pahor.de Antiquariat Daša Pahor GbR Alexander Johnson, Ph.D. & Daša Pahor, Ph.D. Jakob-Klar-Str. 12 Germany - 80796 München +49 89 27 37 23 52 www.pahor.de [email protected] ANSWERS TO THE MOST COMMON QUESTIONS - We offer worldwide free shipping. - We cover the customs fees, provide all the paperwork and deal with the customs. We send outside the EU daily and we are used to taking over the control of exporting and importing. - For all the manuscripts, ordered from outside the EU, please give us approximately 10 days to deal with the additional paperwork. - We offer a 20% institutional discount. - In case you spot an item, that you like, but the end of the fiscal year is approaching, please do not be afraid to ask. We would be glad to put any objects from our offer aside for you and deal with it at your convenience. - We offer original researches and high resolution scans of our maps and prints, which we are happy to forward to the buyers and researchers on request. - For any questions, please e-mail us at: [email protected]. In 2019 we would like to invite you to our stand at the ASEEES Annual Convention in San Francisco, from November 23rd to 26th. -

Taksim Square As 'Heritage Site' and the 2013 Gezi Protests

Whitehead C, Bozoğlu G. Protest, Bodies, and the Grounds of Memory: Taksim Square as 'heritage site' and the 2013 Gezi Protests. Heritage and Society (2017) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/2159032X.2017.1301084 Copyright: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Heritage and Society on 30/03/2017, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/2159032X.2017.1301084 Date deposited: 11/04/2017 Embargo release date: 30 September 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Heritage and Society on 30/04/2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2159032X.2017.1301084 Protest, Bodies and the Grounds of Memory: Taksim Square as ‘heritage site’ and the 2013 Gezi Protests Christopher Whitehead and Gönül Bozoğlu Media, Culture, Heritage, Newcastle University Place incarnates the experiences and aspirations of a people. Place is not only a fact to be explained in the broader frame of space, but it is also a reality to be clarified and understood from the perspectives of the people who have given it meaning. (Yi-Fu Tuan Space and Place, 1979: 387) The current protest movement isn’t about the past; it is about today and tomorrow. It started because a new generation wanted to defend Gezi Park, a public green space, against the violent, abusive manner in which the government sought to sacrifice it to the gods of neo-liberalism and neo- Ottomanism with a plan to build a replica of Ottoman barracks, a shopping mall and apartments (Edhem Eldem, ‘Turkey’s False Nostalgia’, New York Times, 2013). -

THERE IS POWER in a PLAZA: SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, DEMOCRACY, and SPATIAL POLITICS by Kaitlin Kelly-Thompson

THERE IS POWER IN A PLAZA: SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, DEMOCRACY, AND SPATIAL POLITICS by Kaitlin Kelly-Thompson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science West Lafayette, Indiana August 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. S. Laurel Weldon, Chair Department of Political Science Dr. Valeria Sinclair-Chapman Department of Political Science Dr. Rachel L. Einwohner Department of Sociology Dr. Mary Scudder Department of Political Science Approved by: Dr. Cherie D. Maestas 2 For my sister, Stryker, for being my reason to try to make a better world, and for doing more than I ever could to get us there. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Just as cities can facilitate the development of inclusive social movements, my community provided both the material and intellectual support for me while I developed and wrote this dissertation. From the colleagues and mentors who pushed me to develop my theoretical framework to the friends and family who let me couch surf while conducting fieldwork, I could not have finished this without your support and solidarity. First and foremost, this dissertation would not have come into being without the support of my advisor S. Laurel Weldon. Your guidance led me to find my intellectual home, and your inspiring chaos has taught me to think big. Throughout this process, you have modelled the best kind of productive critique pushing both me and the project to become the best it could possibly be, while reminding me to not bury important findings with my own tendency to downplay the positives. -

The Proceedings of the International History of Public Relations Conference 2014

THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL HISTORY OF PUBLIC RELATIONS CONFERENCE 2014 Held at Bournemouth University July 2-3, 2014 Conference Chair: Professor Tom Watson Deputy Chair: Dr Tasos Theofilou Proceedings edited by Professor Tom Watson PROCEEDINGS INDEX Author(s) Title Gülşah Aydin, Pelin Hürmeriç & Duygu Transformation of Turkish Printed Newspapers’ Corporate Aydın Aslaner Cultures Günter Bentele 165 years Public Relations History of a Company: the Case of KRUPP, Germany [Abstract] Thomas H. Bivins When symbols clash: The vanishing myth of woman-as-nation and the rise of woman-as-marketing-metaphor in the early 20th century [Abstract] Carolina Andrea Carbone & Manuel Argentinean public relations: 100 years of constant growth Montaner Rodríguez Edward J. Downes “The (Very Deep) Evolution of the Congressional Press Secretary and the Importance (or Lack Thereof) of an Informed Democracy Ferdinando Fasce Dramatizing Free Enterprise: The National Association of Manufacturers’ Public Relations Campaign in WWII [Abstract] Robert L. Heath & Daymion Waymer John Brown, Public Relations, Terrorism, and Social Capital: “His Truth Goes Marching On” [Abstract] Tom Isaacson Word-of-mouth communication: A historical and modern review of its impact on public relations [Abstract] Paula Keaveney Slavery and the Celebrity Book Tour Susan Kinnear 'One People': National Persuasion and Creativity in early 20th century New Zealand [Abstract] Jan Niklas Kocks & Juliana Raupp ‘Socialist Public Relations’ – a contradictio in adiecto? Rachel Kovacs Nation-Building -

Reframing the Urban Transformation of Çinçin Through Muhtars, Houseworkers, the Usta, and the Kabadayi

DIVERSE LANDSCAPES, DIVERSE WORKS: REFRAMING THE URBAN TRANSFORMATION OF ÇİNÇİN THROUGH MUHTARS, HOUSEWORKERS, THE USTA, AND THE KABADAYI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY GÜLŞAH AYKAÇ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHİLOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE MARCH 2020 Approval of the thesis: DIVERSE LANDSCAPES, DIVERSE WORKS: REFRAMING THE URBAN TRANSFORMATION OF ÇİNÇİN THROUGH MUHTARS, HOUSEWORKERS, THE USTA, AND THE KABADAYI submitted by GÜLŞAH AYKAÇ in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture Department, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Halil Kalıpçılar Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Cânâ Bilsel Head of Department, Architecture Prof. Dr. Güven Arif Sargın Supervisor, Architecture, METU Examining Committee Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ela Alanyalı Aral Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Güven Arif Sargın Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Namık Günay Erkal Architecture, TEDU Prof. Dr. Helga Rittersberger-Tılıç Sociology, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nurbin Paker Kahvecioğlu Architecture, ITU Date: 13.03.2020 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Surname: Gülşah Aykaç Signature: iv ABSTRACT DIVERSE -

Moral Qualities of Space, Historical Consciousness and Symbolic Boundaries in the Beyoğlu District of Istanbul

Moral Qualities of Space, Historical Consciousness and Symbolic Boundaries in the Beyoğlu District of Istanbul Pekka Tuominen Research Series in Anthropology University of Helsinki Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 2 (2016) Social and Cultural Anthropology To be presented for public examination with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki, in Auditorium XV, Main Building of the University of Helsinki on February 27, 2016 at 10. © Pekka Tuominen Cover photo: Pekka Tuominen Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ books@unigrafia.fi PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN 1458-3186 ISBN 978-951-51-1049-7 (Paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-1050-3 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2016 ii Table of Contents List of illustrations vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction Explosive Encounters 1 Spatial Divisions and Appropriate Moral Frameworks 4 Historical Consciousness – Between Grand Narratives and Cultural Intimacy 6 Dynamics of Modernity and Urban Transformation 8 The Structure of the Thesis 10 Fieldwork and Methodology 13 Chapter 1: The Mahalle and the Urban Sphere 20 Defining Urban Spaces 26 Social Organization and Spatial Order of the Mahalle 31 The Boulevard and Egalitarian Urbanity 37 Chapter 2: Qualities of Boundaries and Moral Frameworks of Urbanity 45 Ambiguous Historical Divides – The Historical Peninsula and Beyoğlu 46 Boundaries and Lived Realities 54 Anthropology of Boundaries and Moral Frameworks 62 Access and Safe Passage 67 iii Chapter 3: Becoming an Istanbulite -

The Protestors of Gezi Park Analyzing Discursive Clashes

AUGUST 24TH 2014 THE PROTESTORS OF GEZI PARK ANALYZING DISCURSIVE CLASHES AT THE EDGE OF EUROPE NIKLAS DAVID SOMMER S1195832 BSC EUROPEAN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION BACHELOR THESIS SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT & GOVERNANCE EXAMINATION COMMITTEE DR MARINUS OSSEWAARDE SEDEF TURPER (MA) 1 Abstract The Gezi protests that sparked off in May 2013 in Istanbul turned out to be largest uprising in the history of the Turkish Republic. Especially in terms of the EU candidate country’s secular- Islamic divide, the protests have, in academia, thus far been rather marginally scrutinized. Drawing on this Kulturkampf from a discursive perspective, I will investigate the extent to which the Gezi protestors’ discursive practices show a dialectics of the two clashing discourses in this field - Kemalism and political Islam. Moreover, an inquiry will be made on whether the protest discourse can be considered as a cosmopolitan – a European discourse. After identifying the conceptual traits of the discourses under study, I proceed by conducting a critical discourse analysis (CDA). Deriving my cases from randomly sampled protest texts, the findings eventually show that the Gezi discourse earmarked a cosmopolitan transition from Kemalism to post-Kemalism which, mainly due to the discursive impact of political Islam, further deepened social cleavages in Turkey. Keywords: Gezi protests; Discourses; Kemalism; political Islam; cosmopolitanism 2 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................. -

READING the CRISIS of TURKISH PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACY THROUGH CARL SCHMITT: 1971-1980

READING the CRISIS of TURKISH PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACY THROUGH CARL SCHMITT: 1971-1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY DOLUNAY BULUT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE JULY 2013 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science/Arts / Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Raşit Kaya Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science/Arts/Doctor of Philosophy. (Title and Name) Doç. Dr. Aslı Çırakman Co-Supervisor Supervisor Examining Committee Members (first name belongs to the chairperson of the jury and the second name belongs to supervisor) Prof. Dr. Ayşe Ayata (METU,ADM) Doç. Dr. Aslı Çırakman (METU,ADM) Y.Doç.Dr. Fatma Umut Beşpınar (METU,SOC) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Surname: Dolunay BULUT Signature: iii ABSTRACT CRISIS of TURKISH PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACY THROUGH CARL SCHMITT: 1971-1980 Bulut, Dolunay M.S., Department of Political Science and Public Administration Supervisor : Assoc. -

Stream 5 Article Nº 5-010

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE From CONTESTED_CITIES to Global Urban Justice Stream 5 Article nº 5-010 MAKING THE HETEROTOPIA; GEZI PARK OCCUPY MOVEMENT MERIÇ DEMIR KAHRAMAN BURAK PA KRIS SCHEERLINCK MAKING THE HETEROTOPIA; GEZI PARK OCCUPY MOVEMENT Meriç Demir Kahraman, Ph.D. Candidate Istanbul Technical University – Department of Urban and Regional Planning [email protected] ABSTRACT Following the crisis of 2007-2008, the world witnessed civil protests against socio- economic inequality in numerous cities, from Madrid to Tahrir and from New York to Istanbul. These contemporary social movements represented similarities regarding their demands, their claims to the right to the city, as well as the ways in which they occupied the representational spaces in these cities. Among the cities which gave birth to various Occupy Movements, Istanbul is an important global hub suffering from massive neoliberal urban development projects threatening the natural resources as well as the public spaces of the city (Batuman, 2015). In relation to this context, May 2013 Occupy Gezi Movement was one of the major Occupy protests in the world, emerged as a reaction against the construction of a shopping mall over Gezi Park, one of the few public green spaces left in the heart of the city. Reflecting structural and semantical development process of Gezi Park, as the main contribution of this paper, we situate Occupy Gezi Movement in the conceptual background of “heterotopia” discussing it from both Foucauldian (1967) and Lefebvrian (1970) perspectives and its relevance as a Heterotopic space for future urban practices about making collective space (Foucault, 1967; Lefebvre, 1970; de Solà-Morales, 1992; Avermaete, 2007: Scheerlinck, 2013). -

Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

University of Bath PHD A Political Economy of Insecurity? State and Socio-Economic Actors in the Making of Industrial Relations in Modern Turkey Ozkiziltan, Didem Award date: 2014 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 A Political Economy of Insecurity? State and Socio-Economic Actors in the Making of Industrial Relations in Modern Turkey Didem Ozkiziltan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Social and Policy Sciences September 2013 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with the author. A copy of this thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author. -

Addicted to Teargas After Gezi Nothing Is the Same

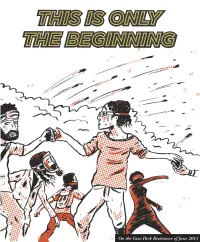

Dancing at the Gezi Commune May 28, 2013 those who had been long-involved Onin defending Gezi Park were clinging to trees, desperately trying to stop the bulldozers, mostly out of blind-conviction and definitely not because they thought they actually had a winning chance. But the days which followed not only blew apart their reality, and every single other person’s in Turkey, but also ushered in the largest, most diffuse and popular rebellion in the country’s history. As the defining moment for a generation in Turkey, the Gezi Park uprising was inundated with a collective form of joy particular to such rebellions. It manifested itself spontaneously with new twists at every turn. While at the time of this publication it might appear that it has lost steam, there is no question that a daring and mischievious spirit of rebellion and resistance has been released into Turkey’s society with consequences still unknown. The following pages contain four pieces written on the Gezi Resistance. The first two were written by Ali Bektaş during the uprising and some of their faults can be attributed to their immediacy. The anonymous contribution to Rolling Thunder #11 and that by Ali B. for Occupied London #5, were written in August 2013. Many thanks to Antonis, Başak, Brian, Dimitris, Emo, Jack, Jami, Lauren, Liam, Maik, Mustafa, Üner, Tim, Wendy, Yiğit and Zeyno for their support. October 2013 5 Burnt-out media trucks in front of the Atatürk Cultural Center CNN Turkey chose to broadcast documentaries about penguins instead of reporting on what was happening on the ground during the first few days of the rebellion. -

The Combined and Uneven Development of Working-Class Capacities in Turkey, 1960–2016

Labor History ISSN: 0023-656X (Print) 1469-9702 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/clah20 The combined and uneven development of working-class capacities in Turkey, 1960–2016 Efe Can Gürcan & Berk Mete To cite this article: Efe Can Gürcan & Berk Mete (2018): The combined and uneven development of working-class capacities in Turkey, 1960–2016, Labor History, DOI: 10.1080/0023656X.2019.1537027 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2019.1537027 Published online: 24 Oct 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 40 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=clah20 LABOR HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2019.1537027 The combined and uneven development of working-class capacities in Turkey, 1960–2016 Efe Can Gürcana and Berk Meteb aSchool for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Coquitlam, Canada; bDepartment of Sociology, Maltepe University, Istanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY How have Turkey’s working-class capacities been evolving since the Received 11 December 2017 1960s? What have been the peculiarities of Turkey’s import-substitution- Accepted 6 August 2018 alist model and later integration into the neoliberal economic landscape, KEYWORDS as they pertain to the transformation of the Turkish working class? Our Class capacities; combined aim here is two-fold: (i) to contribute to a systematic understanding of and uneven development; the historical development of Turkey’s working class; and (ii) to develop a import substitutionalism; new conceptual lens for class-capacity analysis from a combined and neoliberalism; unionism uneven development perspective.