Canada's Quest for New Submarines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Canadian Armed Forces in Nova Scotia Information

2019/2020 THE CANADIAN ARMED FORCES IN NOVA SCOTIA INFORMATION DIRECTORY AND SHOPPING GUIDE LES FORCES ARMÉES CANADIENNES DANS LA NOUVELLE ÉCOSSE RÉPERTOIRE D’INFORMATIONS ET GUIDE À L’INTENTION DES CONSOMMATEURS photo by Frank Grummett Welcome aboard HMCS Sackville, Canada’s offi cial Naval Memorial since 1985, and experience living history in a Second World War Convoy Escort! HMCS Sackville was built in Saint John, New Brunswick and named after the Town of Sackville, NB. She was part of a large ship-building programme to respond to the threat posed by German U-boats in the North Atlantic, and was commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy in December 1941. HMCS Sackville is the last of Canada’s 123 wartime corvettes that played a major role in the Allies winning the pivotal Battle of the Atlantic (1939-1945). HMCS Sackville, her sister corvettes and other ships of the rapidly expanded Royal Canadian Navy, operating out of Halifax, St John’s and other East Coast ports, were front and centre during the lengthy war at sea. HMCS Sackville’s most memorable encounter occurred in August 1942 when she engaged three U-boats in a 24-hour period while escorting a convoy that was attacked near the Grand Banks. She put two of the U-boats out of action before they were able to escape. A year later, when another convoy was attacked by U-boats, HMCS Sackville engaged one U-boat with depth charges; however several merchant vessels and four naval escorts – including HMCS St. Croix - were torpedoed and sunk with heavy loss of life. -

RCN Fleet Poster

/// VESSELS IN SERVICE /// VESSELS IN DEVELOPMENT HMCS HALIFAX 330 HMCS HARRY DEWOLF 430 HALIFAX CLASS MULTI-ROLE PATROL FRIGATE (FFH) HARRY DEWOLF ARCTIC AND OFFSHORE PATROL VESSEL HMCS VANCOUVER 331 CLASS (AOPV) HMCS MARGARET BROOKE 431 HMCS VILLE DE QUÉBEC 332 Standard Displacement 4,770 tonnes Length 134.1 metres HMCS MAX BERNAYS 432 Standard Displacement 6,440 tonnes Length 103 metres HMCS TORONTO 333 Beam 16.4 metres Complement 225 personnel HMCS WILLIAM HALL 433 HMCS REGINA 334 Beam 19 metres Complement 65 personnel HMCS FRÉDÉRICK ROLETTE 434 Armament: Phalanx 20mm CIWS, ESSM SAMs, Bofors 57mm gun, Harpoon HMCS CALGARY 335 SSMs, twin MK 46 torpedo tubes, heavy (.50 cal) machine guns Armament: BAE Mk 38 Mod 2 gun, heavy (.50 cal) machine guns HMCS MONTRÉAL 336 HMCS FREDERICTON 337 In 2016, the last of the 12 Halifax-class helicopter-carrying frigates, the core of Scheduled for delivery in 2018, the Harry DeWolf-class Arctic and Offshore Patrol HMCS WINNIPEG 338 the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) fleet, completed the Halifax-Class Modernization Vessels will be ice-capable ships enabling armed sea-borne surveillance of HMCS CHARLOTTETOWN 339 project. This involved the installation of state-of-the-art radars, defences and arma- Canada’s waters, including the Arctic, providing government situational aware- /// HALIFAX CLASS ness of activities and events in these remote regions. The Harry DeWolf class, HMCS ST. JOHN’S 340 ments. The armaments combine anti-submarine, anti-surface and anti-air systems to deal with threats below, on and above the sea surface. MULTI-ROLE PATROL FRIGATE (FFH) in cooperation with other partners in the Canadian Armed Forces and other gov- HMCS OTTAWA 341 ernment departments, will be able to assert and enforce Canadian sovereignty, when and where necessary. -

Winter 2015 ARGONAUTA

ARGONAUTA The Newsletter of The Canadian Nautical Research Society / Société canadienne pour la recherche nautique Volume XXXII Number 1 Winter 2015 ARGONAUTA Founded 1984 by Kenneth MacKenzie ISSN No. 2291-5427 Editors Isabel Campbell and Colleen McKee Jean Martin ~ French Editor Winston (Kip) Scoville ~ Production/Distribution Manager Argonauta Editorial Office c/o Isabel Campbell 2067 Alta Vista Dr. Ottawa ON K1H 7L4 e-mail submissions to: [email protected] or [email protected] ARGONAUTA is published four times a year—Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn Executive Officers President: Chris Madsen, North Vancouver, BC Past President: Maurice Smith, Kingston, ON 1st Vice President: Roger Sarty, Kitchener, ON 2nd Vice President: Richard Mayne, Trenton, ON Treasurer: Errolyn Humphreys, Ottawa, ON Secretary: Rob Davison, Waterloo, ON Membership Secretary: Faye Kert, Ottawa, ON Councillor: Walter Lewis, Grafton, ON Councillor: Vacant Councillor: Vacant Councillor: Vacant Membership Business: 200 Fifth Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 2N2, Canada e-mail: [email protected] Annual Membership including four issues of ARGONAUTA and four issues of THE NORTHERN MARINER/LE MARIN DU NORD: Within Canada: Individuals, $70.00; Institutions, $95.00; Students, $25.00 International: Individuals, $80.00; Institutions, $105.00; Students, $35.00 Our Website: http://www.cnrs-scrn.org Copyright © CNRS/SCRN and all original copyright holders In this issue of the Argonauta Editorial 1 President’s Corner 3 The More Northerly Route - Looking Back 70 Years 5 -

Canada's Northern Strategy Under Prime Minister Stephen Harper

Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security Canada’s Northern Strategy under Prime Minister Stephen Harper: Key Speeches and Documents, 2005-15 P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Ryan Dean Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security (DCASS) ISSN 2368-4569 Series Editors: P. Whitney Lackenbauer Adam Lajeunesse Managing Editor: Ryan Dean Canada’s Northern Strategy under the Harper Conservatives: Key Speeches and Documents on Sovereignty, Security, and Governance, 2005-15 P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Ryan Dean DCASS Number 6, 2016 Front Cover: Rt. Hon. Stephen Harper speaking during Op NANOOK 2012, Combat Camera photo IS2012-5105-06. Back Cover: Rt. Hon. Stephen Harper speaking during Op LANCASTER 2006, Combat Camera photo AS2006-0491a. Centre for Military, Security and Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Strategic Studies St. Jerome’s University University of Calgary 290 Westmount Road N. 2500 University Dr. N.W. Waterloo, ON N2L 3G3 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 519.884.8110 ext. 28233 Tel: 403.220.4030 www.sju.ca/cfpf www.cmss.ucalgary.ca Arctic Institute of North America University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW, ES-1040 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403-220-7515 http://arctic.ucalgary.ca/ Copyright © the authors/editors, 2016 Permission policies are outlined on our website http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/research/arctic-document-series Canada’s Northern Strategy under the Harper Government: Key Speeches and Documents on Sovereignty, Security, and Governance, 2005-15 P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. and Ryan Dean, M.A. Contents List of Acronyms ..................................................................................................... xx Introduction ......................................................................................................... xxv Appendix: Federal Cabinet Ministers with Arctic Responsibilities, 2006- 2015 ........................................................................................................ xlvi 1. -

Once Beleaguered Canadian Submarines Now a Potent International Force

Once beleaguered Canadian submarines now a potent international force They run silent and they run deep. But, the problem with Canadian submarines being largely out-of-sight, out-of-mind and overshadowed by the army in Afghanistan is that Canadians can’t connect with the notion that Canada’s submarines have emerged as a potent force on the international stage. Unfortunately, to date, the biggest news story involving Canada’s four diesel-electric Victoria Class submarines – taken over from the United Kingdom in a 1998 eight-year lease-to-buy agreement – was the October 2004 fire aboard HMCS Chicoutimi while in transit from Britain, killing one Canadian submariner and injuring nine others. There is good reason why the lethal fire received the negative news coverage: a fire is one of the absolute worst things that could ever happen aboard a submarine and it did. But, coupled with the mostly-unfair criticism they received for being acquired second-hand from the British who launched them between 1990 and 1992, many likened them to used-car lemons. The British mothballed them in 1994 and 1995 in favor of nuclear submarines and there were numerous technical problems bringing them back into service for the transit between Britain and Canada, let alone their retrofitting for Mark-48 torpedoes and Canadian communications and sonar equipment. But, seeing HMCS Victoria, formerly HMS Unseen, in dry dock in Esquimalt, B.C., while it was in retrofit in May 2004 was a little overwhelming for this prairie resident who had only seen diagrams and pictures of them. No one picture captures the breath-taking size of the nearly seven-storey tall Leviathans, let alone their three-quarters-the-size-of-a-football-field length. -

PUBLICATIONS SPP Research Paper

PUBLICATIONS SPP Research Paper Volume 10:22 September 2017 2016 STATUS REPORT ON MAJOR EQUIPMENT PROCUREMENT David G. Perry SUMMARY The Department of National Defence made some progress in procurement in 2016 despite obstacles that included a continued drop in spending, the advent of a new federal Liberal government and uncertainty over the outcome of the Defence Policy Review. Four trends affected defence acquisitions in 2016. These include an ongoing slippage in recapitalizing the Canadian Armed Forces, some encouraging moves made on the shipbuilding and fighter jet files, mixed progress on implementing the 2014 Defence Procurement Strategy, and uncertainty over the Defence Policy Review. It is also too early to tell how the Trudeau government’s Policy on Results, known as the “deliverology” approach, will play out for defence procurement. However, Budget 2016’s major focus was not on defence, and it shifted some funding for capital equipment to a new endpoint of 2045. This suggests that delay in the overall defence procurement program continues. While the Liberals kept their pledge to make investment in the Royal Canadian Navy a priority, they also made good last year on a negative promise – not to purchase the F-35 stealth fighter bomber. However, further slowing things is the Liberals’ refusal to launch a competition to replace it until the Defence Policy Review is published. The government has made this situation more fraught with its intention to buy 18 Boeing Super Hornet fighter jets as interim aircraft, since Liberal policy requires the Royal Canadian Air Force to be capable of meeting both NORAD’s and NATO’s operational needs simultaneously. -

2021-06-28-13

Monday June 28, 2021 Volume 55, Issue 13 www.tridentnewspaper.com Operation CARIBBE continues The coxswain of HMCS Shawinigan watches over the bridge wing as the ship departs from Miami, Florida to take part in Operation CARIBBE on June 10. Note the individual pictured and the photographer are not named to preserve operational security. CAF PHOTO 2 TRIDENT NEWS JUNE 28, 2021 www.tridentnewspaper.com Making waves: Trio of HMCS Halifax sailors write music and perform together Editor: Ryan Melanson [email protected] By Joanie Veitch, (902) 427-4235 Trident Staff Reporter: Joanie Veitch [email protected] When Sailor Third Class John Sty- — while playing guitar in the Junior College in Ottawa, he offered to help out (902) 427-4238 miest left on a six-month deployment Ranks mess. with production and sound. with HMCS Halifax on January 1st, S3 Stymiest’s rap and hip-hop style “He started playing with us...and Editorial Advisor: Margaret Conway [email protected] he brought his acoustic guitar, figur- blends with S1 van der Kamp’s sing- integrated perfectly. As he is more of 902-721-0560 ing it would help pass the time on his er-songwriter background to come up a producer he gave us advice on that first deployment. He had no idea that with something they describe as “folk side which is incredibly appreciated as Editorial Advisor: Ariane Guay-Jadah in just a few weeks he would not only rap” — “think Dallas Green meets sometimes that’s what you need to not [email protected] find two other sailors to jam with, the Classified meets Linkin Park,” said S3 get too carried away,” said S1 van der 902-721-8341 trio would create original music and Stymiest, who goes by the stage name Kamp, who plays under the moniker www.tridentnewspaper.com play at an event in front of the entire Johnny GASH, in a nod to his navy VDK. -

2015 Status Report on Major Defence Equipment Procurements

2015 Status Report on Major Defence Equipment Procurements by David Perry December, 2015 formerly Canadian Defence & Foreign Affairs Institute (CDFAI) POLICY PAPER 2015 STATUS REPORT ON MAJOR DEFENCE EQUIPMENT PROCUREMENTS by David Perry Senior Analyst, CGAI December, 2015 Executive Summary FederalCanada elections is struggling may be to good fully for develop, democracy, sell but and the move campaigns its energy — particularly resources the. Thislengthy is onea dramatic recently heldchange in Canadafrom the — recent can be pastcrippling where for the plans U.S. to has better provided arm our stable military. growth Just inbefore demand the election for energy was called,supplied there by were the publicprovinces, signs offrom important hydrocarbons progress being to electricity made in what. Current has long circumstances been a frustratingly now slowchallenge and bureaucratically this relationship, complex adding procurement environmental, process. policy But and then economic the campaign hurdles left thatthe Department exacerbate ofthe National impact ofDefence fluctuations and other in world federal demand departments and pricing. unable to secure approvals from either a defence minister or the Treasury Board, until the election ended and the new prime minister appointed the In addition, competitive interaction between provinces, aboriginal land owners and special currentinterest cabinet. groups complicate and compound the issues of royalty returns, regulatory authority and Theredirection, had alreadyland-use been management upheaval prior and to long that:- termIn the marketfirst seven opportunities months of 2015, for Canadianthe three seniorcompanies leaders. There is no strategic document guiding the country’s energy future. at the Canadian Forces and the Defence Department (including the minister) had been replaced, along withAs the many steward other peopleof one criticalof the tolargest, the procurement most diverse process. -

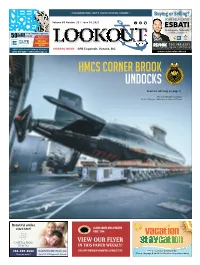

Hmcs Corner Brook Undocks

NEED • CANADIAN MILITARY’S TRUSTED NEWS SOURCE • Buying or Selling? I CAN HELP! CHRIS NEEDMORE Volume 66 Number 23 | June 14, 2021 ESBATI MORE Knowledgeable, Trustworthy SPACE? and Dedicated Service SPACE?FOR RENTAL PERIODS! % OFF 2 *Some restrictons apply PLUS... Receive a SPACE?50 military discount: 10% OFF EACH FOLLOWING newspaper.com MONTH 250.744.3301 [email protected] 4402 Westshore Parkway, Victoria MARPAC NEWS CFB Esquimalt, Victoria, B.C. (778) 817-1293 • eliteselfstorage.ca www.victoriaforsale.ca 4402 Westshore Parkway, Victoria (778) 817-1293 • eliteselfstorage.ca HMCS CORNER BROOK UNDOCKS Read the full story on page 3. Photo credit: James Charsley, Project Manager Submarines, Babcock Canada Beautiful smiles start here! Island Owned and Operated since 1984. VacatLon Capital Park VIEW OUR FLYER StaycatLon Dental IN THIS PAPER WEEKLY! 250-590-8566 CapitalParkDental.com check out our newly renovated esquimalt store Enjoy a summer holiday in BC. Français aussi ! Suite 110, 525 Superior St, Victoria Check out page 8 and 9 for Vacation Staycation ideas! 2 • LOOKOUT Canadian Military’s trusted news sourCe • CeleBratinG 77 years ProVidinG rCn news June 14, 2021 #NPSW CURTIS ROD MIKE HAMILTON WOOD MCLEAN Service Desk Officer, Main Warehouse Manager Chief Fire Prevention Base Information Services, (Naval Supply Depot), Officer, Client Services Base Logistics, Colwood CFB Esquimalt Fire Rescue How long have you been working as a public servant? How long have you been working as a public servant? How long have you been working as a public servant? 16 years I started June 20, 2000 as an STS 3 Term employee. 13 years What’s the best part of your job? What’s the best part of your job? What’s the best part of your job? Being able to resolve members’ IT issues. -

By Eric Wertheim

Copyright © 2010, Proceedings, U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland (410) 268-6110 www.usni.org By Eric Wertheim rom counter-piracy patrols off the coast of Somalia to navies of the world have proven once again that in the age of hy- ballistic-missile defense off the waters of North Korea, brid warfare, maritime forces are at the helm, leading the way. Fthe past year of naval operations has highlighted the flex- This review of the world’s navies presents a snapshot of activities ibility of global maritime power. As militaries around the globe and developments during the past year. It is arranged by region, with face conventional threats mixed with asymmetric challenges, the nations discussed alphabetically under each subheading. Australia and Asia research and mine-countermeasures capa- took part in an around-the-world tour that No one can accuse Australia of under- bilities are planned, as are new maritime included a successful anti-piracy patrol off reaching when it comes to current patrol aircraft, unmanned aerial ve- Yemen and Somalia. During the exercises and future defense planning. hicles, and helicopters. she showcased her impressive modernized During 2009 Australia’s On the amphibious front, weapons including the recent addition government released a new the two Canberra-class of an eight-tube vertical-launch missile white paper calling for vast 27,800-ton large-deck am- system carrying 32 ESSM missiles. The naval enhancements during phibious ships are being newly modernized warships also retain the course of the next 20 built in Spain with even- the capability to carry two helicopters years. -

Canadian Military Journal, Issue 14, No 3

Vol. 14, No. 3, Summer 2014 CONTENTS 3 EDITOR’S CORNER 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR CANADA’S NAVY 7 Does Canada Need Submarines? by Michael Byers 15 The Contribution of Submarines to Canada’s Freedom of Action on the Cover World Stage Landing of the First Canadian by Paul T. Mitchell Division at Saint-Nazaire, by Edgar Bundy Rutherford MILITARY INTELLIGENCE Canadian War Museum 19710261-0110 26 The Past, Present and Future of Chinese Cyber Operations by Jonathan Racicot SENIOR CIVIL SERVANTS AND NATIONAL DEFENCE 38 Unelected, Unarmed Servants of the State: The Changing Role of Senior Civil Servants inside Canada’s National Defence by Daniel Gosselin MILITARY HISTORY 53 Know Your Ground: A Look at Military Geographic Intelligence and Planning in the Second World War by Lori Sumner 64 The Colonial Militia of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1853–1871 Does Canada Need by Adam Goulet Submarines? VIEWS AND OPINIONS 70 The Duty to Remember is an Integral Part of Bilateral Relations by Marcel Cloutier 73 Whatever Happened to Mission Command in the CAF? by Allan English 76 Compulsory Release and Duty of Fairness by Kostyantyn Grygoryev COMMENTARY 80 The Aurora Chronicles by Martin Shadwick JOURNAL REVIEW ESSAY The Past, Present and 85 Situational Awareness Depends upon Intelligence Gathering, but Good Future of Chinese Preparation Depends upon Knowledge of the Issues Cyber Operations by Sylvain Chalifour 86 BOOK REVIEWS Canadian Military Journal / Revue militaire canadienne is the official professional journal of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence. It is published quarterly under authority of the Minister of National Defence. -

Peace-Time Attrition Expectations for Naval Fleets an Analysis of Post-WWII Maritime Incidents

CAN UNCLASSIFIED Peace-time attrition expectations for naval fleets An analysis of post-WWII maritime incidents David W. Mason DRDC – Centre for Operational Research and Analysis Defence Research and Development Canada Reference Document DRDC-RDDC-2017-D086 May 2018 CAN UNCLASSIFIED CAN UNCLASSIFIED IMPORTANT INFORMATIVE STATEMENTS Disclaimer: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada (Department of National Defence) makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, of any kind whatsoever, and assumes no liability for the accuracy, reliability, completeness, currency or usefulness of any information, product, process or material included in this document. Nothing in this document should be interpreted as an endorsement for the specific use of any tool, technique or process examined in it. Any reliance on, or use of, any information, product, process or material included in this document is at the sole risk of the person so using it or relying on it. Canada does not assume any liability in respect of any damages or losses arising out of or in connection with the use of, or reliance on, any information, product, process or material included in this document. This document was reviewed for Controlled Goods by Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) using the Schedule to the Defence Production Act. Endorsement statement: This publication has been published by the Editorial Office of Defence Research and Development Canada, an agency of the Department of National Defence of Canada. Inquiries can be sent to: [email protected]. This document refers to an attachment. To request access to this attachment, please email [email protected], citing the DRDC document number.