CNR) Is a “Not-For-Profit” the Content Diversity and High Quality “Feel” Presently Publication Depending Upon Its Subscription Base, the Found in the Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Instruction Sheet (.Pdf)

Belcher Bits Decal BD17: Seafire, Firefly, Sea Fury & Tracker 1/72 In December 1945, the Naval Air branch of the Royal Canadian Navy was estab- lished and initially equipped with the Supermarine Seafire XV and Fairy Firefly FR.1. By 1949, the Seafire had been replaced by the Hawker Sea Fury, and the original batch of Fireflies upgraded to FR IV and AS.5, being phased out a year later by the Grumman TBM. These aircraft represent the first stages of the RCN Naval Air branch as it was being developed from its Fleet Air Arm roots. By the mid-50s, Canada’s operational role was changing and becoming more closely linked with the US, and the final group of aircraft used by the RCN were all US designs (F2H Banshee and S2F Tracker) This decal sheet allows the modeller to build a Seafire XV and Firefly FR.1 in either of the operational schemes in which they served. It also provides markings for the first carrier based operational scheme for the Sea Fury. Some of the Sea Furies were originally delivered and used in the current FAA scheme of EDSG over Sky, but that scheme was not common. Finally, this sheet provides markings for Grumman Trackers in RCN service. Although this aircraft lasted well past the RCN era, this sheet covers the inital schemes. Unlike many Belcher Bits decals, this sheet is not generic, and specific aircraft are covered, although common lettering sizes mean some other Seafires and Fireflies are possible with a bit of mixing and matching. Specific schemes illustrated are: 1. -

The Canadian Armed Forces in Nova Scotia Information

2019/2020 THE CANADIAN ARMED FORCES IN NOVA SCOTIA INFORMATION DIRECTORY AND SHOPPING GUIDE LES FORCES ARMÉES CANADIENNES DANS LA NOUVELLE ÉCOSSE RÉPERTOIRE D’INFORMATIONS ET GUIDE À L’INTENTION DES CONSOMMATEURS photo by Frank Grummett Welcome aboard HMCS Sackville, Canada’s offi cial Naval Memorial since 1985, and experience living history in a Second World War Convoy Escort! HMCS Sackville was built in Saint John, New Brunswick and named after the Town of Sackville, NB. She was part of a large ship-building programme to respond to the threat posed by German U-boats in the North Atlantic, and was commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy in December 1941. HMCS Sackville is the last of Canada’s 123 wartime corvettes that played a major role in the Allies winning the pivotal Battle of the Atlantic (1939-1945). HMCS Sackville, her sister corvettes and other ships of the rapidly expanded Royal Canadian Navy, operating out of Halifax, St John’s and other East Coast ports, were front and centre during the lengthy war at sea. HMCS Sackville’s most memorable encounter occurred in August 1942 when she engaged three U-boats in a 24-hour period while escorting a convoy that was attacked near the Grand Banks. She put two of the U-boats out of action before they were able to escape. A year later, when another convoy was attacked by U-boats, HMCS Sackville engaged one U-boat with depth charges; however several merchant vessels and four naval escorts – including HMCS St. Croix - were torpedoed and sunk with heavy loss of life. -

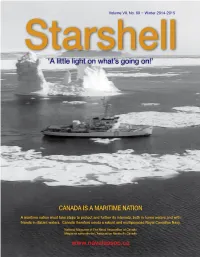

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 69 ~ Winter 2014-2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… To date, the Royal Canadian Navy’s only purpose-built, ice-capable Arctic Patrol Vessel, HMCS Labrador, commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy July 8th, 1954, ‘poses’ in her frozen natural element, date unknown. She was a state-of-the- Starshell art diesel electric icebreaker similar in design to the US Coast Guard’s Wind-class ISSN-1191-1166 icebreakers, however, was modified to include a suite of scientific instruments so it could serve as an exploration vessel rather than a warship like the American Coast National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Guard vessels. She was the first ship to circumnavigate North America when, in Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada 1954, she transited the Northwest Passage and returned to Halifax through the Panama Canal. When DND decided to reduce spending by cancelling the Arctic patrols, Labrador was transferred to the Department of Transport becoming the www.navalassoc.ca CGSS Labrador until being paid off and sold for scrap in 1987. Royal Canadian Navy photo/University of Calgary PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele In this edition… PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] NAC Conference – Canada’s Third Ocean 3 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] The Editor’s Desk 4 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] The Bridge 4 The Front Desk 6 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] NAC Regalia Sales 6 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

Okanagan Nation E-News

S Y I L X OKANAGAN NATION E-NEWS April 2010 Okanagan Nation Jr. Girls Bring Home Provincial Championship Table of Contents HMCS Okanagan 2 Syilx Youth Unity Run 3 Browns Creek 4 Update Child & Family 6 NRLUT Update FN Leaders 7 Denounce Fed Funding Cuts Health Hub 8 Columbia River 9 93,000 Sockeye 10 Released Sturgeon 11 Gathering AA Roundup 12 Photo: Team Mng Lisa Reid, Ashley McGinnis, Dina Brown, Jasmine Reid, Janessa Lambert, Coach Peter Waardenburg, Erica Swan, Jade Waardenburg, Nicola Terbasket, Coach Amanda Montgomery, Kirsten Lindley, Front: Jade Sargent Family 13 Missing Courtney Louie Intervention The Syilx, Okanagan Nation, Jr Girls basketball ball it was stolen by Reid, passed to Sargent and Society Conf ONA Bursary 14 team brought home the Championship and she did a lay in to win the game. Most Sportsmanlike Team after playing 8 R Native Voice 15 “Okanagan girls were full value for the win, University Camp 16 games in Prince Rupert during Spring Break. hard working and all the class in the world.” Fish Lake 17 The final four games were all nail biters, said said Kitimat coach Keith Nyce. What’s Reid; the gym was vibrating with the fans from Happening 18 Other awards included MVP, Jade Toll Free all the villages cheering on their nations. Waardenburg, Best Defense and All Star In the final game against Kitimat there was only 1-866-662-9609 Jasmine Reid, and All Star Ashley McGinnis 9 seconds left, Okanagan down by 2, when Waardenburg drew the foal that would take The Okanagan Nation will host the 2011 Jr All her to the free throw line. -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

Forget Retail! Buy Wholesale Direct! Over $10.6 Million Inventory Available Same Day

Forget Retail! Buy Wholesale Direct! Over $10.6 million inventory available same day. Family owned for more than 40 years. Value to premium parts available. 902-423-7127 | WWW.CANDRAUTOSUPPLY.CA | 2513 AGRICOLA ST., HALIFAX 144518 Monday, June 25, 2018 Volume 52, Issue 13 www.tridentnewspaper.com CAF members send Canada Day greetings from the flight deck of HMCS St. John’s during Op REASSURANCE. CPL TONY CHAND, FIS Happy Canada Day from HMCS St. John’s RCAF Honorary Colonel HMCS Haida designated Kayak trip supports Atlantic Regional conference Pg. 7 RCN Flagship Pg. 9 HMCS Sackville Pg. 12 Powerlifting Pg. 20 CAF Veterans who completed Basic Training and are Honorably Discharged are eligible for the CANEX No Interest Credit Plan. (OAC) CANADA’S MILITARY STORE LE MAGASIN MILITAIRE DU CANADA Canex Windsor Park | 902-465-5414 152268 2 TRIDENT NEWS JUNE 25, 2018 Former NESOPs welcomed back to RCN through Skilled Re-enrollment Initiative By Ryan Melanson, ance in some cases, was a factor in Trident Staff bringing him back to the Navy. “It was something I was consider- The RCN has been making an extra ing, but I was still enjoying my time effort to bring recently retired sailors with my family and I wasn’t sure back to the organization, and the two about it. When I got the letter and first members to take advantage of heard about this, that definitely had this Skilled Re-enrollment Initiative an impact on my decision.” have now made it official. In addressing the brand new re- LS Kenneth Squibb and LS Steven cruits at the ceremony, RAdm Baines Auchu, both NESOPs with sailing recalled his own enrollment in the experience, who each retired from CAF nearly 31 years ago, and the un- the Navy less than two years ago, will certainty that came with it. -

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ Volume XII, No. 54 Spring 2011 National Magazine of the Naval Officers Association of Canada Magazine nationale de l’association des officiers de la marine du Canada In this issue The editor’s cabin 2 Our cover and the Editor’s Cabin There is insufficient space here to adequately describe the 3 Where Land Ends, Life Begins trials that befell my miniscule publishing ‘empire’ following SPRING 2011 4 Commentary: ‘You heard it hear first’ the last issue of Starshell. The old Mac G4 that housed all my 6 Naval Syllogisms for Canada page layout software (including an ancient version of Adobe 8 Shipboard Tactical Data Systems Pagemaker) as well as all my newsletter templates (I publish four 10 View from the Bridge other periodicals besides this one), graphics, fonts, etc., suffered 10 The Front Desk a hard drive crash and the aforementioned was forever lost! Sensing such a calamity STARSHELL 11 Mail Call could well be in the offing, I had purchased a new Apple iMac computer last year, 12 The Briefing Room but had been putting off the substantial investment in new publishing software. The 13 Schober’s Quiz #53 hard drive crash effectively put me out of business; a trip to the local Apple com- 13 NOAC Regalia puter dealer was no longer an option. So—as evidenced by a much lighter wallet—I 15 The Edwards’ Files: ‘Captain’s Beer’ am now armed with the latest versions of Adobe In Design, Photoshop, Illustrator 16 Broadsides: ‘Honking Big Ships’ and Acrobat Pro. -

HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and Life in the West Coast Reserve Fleet, 1913-1918

Canadian Military History Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 2 2010 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Richard O. Mayne "“For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918." Canadian Military History 19, 1 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne n 30 October 1918, Arthur for all activities related to Canada’s Ashdown Green, a wireless Abstract: HMCS Galiano is remembered oceans and inland waters including O mainly for being the Royal Canadian operator on Triangle Island, British Navy’s only loss during the First World the maintenance of navigation Columbia, received a bone-chilling War. However, a close examination aids, enforcement of regulations signal from a foundering ship. of this ship’s history not only reveals and the upkeep of hydrographical “Hold’s full of water,” Michael John important insights into the origins and requirements. Protecting Canadian identity of the West Coast’s seagoing Neary, the ship’s wireless operator sovereignty and fisheries was also naval reserve, but also the hazards and desperately transmitted, “For God’s navigational challenges that confronted one of the department’s key roles, Sake send help.” Nothing further the men who served in these waters. -

ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018

HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018 Action Stations Winter 2018 1 Volume 37 - Issue 1 ACTION STATIONS! Winter 2018 Editor and design: Our Cover LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup, RCN Chair - Commemorations, CNMT [email protected] Editorial Committee LS ret’d Steve Rowland, RCN Cdr ret’d Len Canfield, RCN - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas, RCN - Exec. Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Officer Editorial Associates Major ret’d Peter Holmes, RCAF Tanya Cowbrough Carl Anderson CPO Dean Boettger, RCN webmaster: Steve Rowland Permanently moored in the Thames close to London Bridge, HMS Belfast was commissioned into the Royal Photographers Navy in August 1939. In late 1942 she was assigned for duty in the North Atlantic where she played a key role Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart, RCN in the battle of North Cape, which ended in the sinking Cdr ret’d Bill Gard, RCN of the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst. In June 1944 Doug Struthers HMS Belfast led the naval bombardment off Normandy in Cdr ret’d Heather Armstrong, RCN support of the Allied landings of D-Day. She last fired her guns in anger during the Korean War, when she earned the name “that straight-shooting ship”. HMS Belfast is Garry Weir now part of the Imperial War Museum and along with http://www.forposterityssake.ca/ HMCS Sackville, a member of the Historical Naval Ships Association. HMS Belfast turns 80 in 2018 and is open Roger Litwiller: daily to visitors. http://www.rogerlitwiller.com/ HMS Belfast photograph courtesy of the Imperial -

100 Years of Submarines in the RCN!

Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ Volume VII, No. 65 ~ Winter 2013-14 Public Archives of Canada 100 years of submarines in the RCN! National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca Please help us put printing and postage costs to more efficient use by opting not to receive a printed copy of Starshell, choosing instead to read the FULL COLOUR PDF e-version posted on our web site at http:www.nava- Winter 2013-14 lassoc.ca/starshell When each issue is posted, a notice will | Starshell be sent to all Branch Presidents asking them to notify their ISSN 1191-1166 members accordingly. You will also find back issues posted there. To opt out of the printed copy in favour of reading National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Starshell the e-Starshell version on our website, please contact the Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada Executive Director at [email protected] today. Thanks! www.navalassoc.ca PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh OUR COVER RCN SUBMARINE CENTENNIAL HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele The two RCN H-Class submarines CH14 and CH15 dressed overall, ca. 1920-22. Built in the US, they were offered to the • RCN by the Admiralty as they were surplus to British needs. PRESIDENT Jim Carruthers, [email protected] See: “100 Years of Submarines in the RCN” beginning on page 4. PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] TREASURER • Derek Greer, [email protected] IN THIS EDITION BOARD MEMBERS • Branch Presidents NAVAL AFFAIRS • Richard Archer, [email protected] 4 100 Years of Submarines in the RCN HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

A HISTORY of GARRISON CALGARY and the MILITARY MUSEUMS of CALGARY

A HISTORY OF GARRISON CALGARY and The MILITARY MUSEUMS of CALGARY by Terry Thompson 1932-2016 Terry joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1951, where he served primarily as a pilot. Following retirement in 1981 at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, he worked for Westin Hotels, the CBC for the 1984 Papal visit, EXPO 86, the 1988 Winter Olympic Games and the 1990 Goodwill Games. Following these busy years, he worked in real estate and volunteered with the Naval Museum of Alberta. Terry is the author of 'Warriors and the Battle Within'. CHAPTER EIGHT THE ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY In 2010, the Royal Canadian Navy celebrated its 100th anniversary. Since 1910, men and women in Canada's navy have served with distinction in two World Wars, the Korean conflict, the Gulf Wars, Afghanistan and Libyan war and numerous peace keeping operations since the 1960s. Prior to the 20th Century, the dominions of the British Empire enjoyed naval protection from the Royal Navy, the world's finest sea power. Canadians devoted to the service of their country served with the RN from England to India, and Canada to Australia. British ships patrolled the oceans, protecting commerce and the interests of the British Empire around the globe. In the early 1900s, however, Germany was threatening Great Britain's dominance of the seas, and with the First World War brewing, the ships of the Royal Navy would be required closer to home. The dominions of Great Britain were now being given the option of either providing funding or manpower to the Royal Navy, or forming a naval force of their own. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Page Certificate of Examination I

The End of the Big Ship Navy: The Trudeau Government, the Defence Policy Review and the Decommissioning of the HMCS Bonaventure by Hugh Avi Gordon B.A.H., Queen’s University at Kingston, 2001. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ______________________________________________________________ Dr. D.K. Zimmerman, Supervisor (Department of History) ______________________________________________________________ Dr. P.E. Roy, Departmental Member (Department of History) ______________________________________________________________ Dr. E.W. Sager, Departmental Member (Department of History) ______________________________________________________________ Dr. J.A. Boutilier, External Examiner (Department of National Defence) © Hugh Avi Gordon, 2003 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisor: Dr. David Zimmerman ABSTRACT As part of a major defence review meant to streamline and re-prioritize the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), in 1969, the Trudeau government decommissioned Canada’s last aircraft carrier, HMCS Bonaventure. The carrier represented a major part of Maritime Command’s NATO oriented anti- submarine warfare (ASW) effort. There were three main reasons for the government’s decision. First, the carrier’s yearly cost of $20 million was too much for the government to afford. Second, several defence experts challenged the ability of the Bonaventure to fulfill its ASW role. Third, members of the government and sections of the public believed that an aircraft carrier was a luxury that Canada did not require for its defence. There was a perception that the carrier was the wrong ship used for the wrong role.