TABLE of CONTENTS Page Certificate of Examination I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

Harry George Dewolf 1903 - 2000

The Poppy Design is a registered trademark of The Royal Canadian Legion, Dominion Command and is used under licence. Le coquelicot est une marque de commerce enregistrée de La Direction nationale de La Légion royale canadienne, employée Le coquelicot est une marque de commerce enregistrée La Direction nationale sous licence. de La Légion royale canadienne, Dominion Command and is used under licence. The Royal Canadian Legion, Design is a registered trademark of The Poppy © DeWolf family collection - Collection de la famille DeWolf © DeWolf HARRY GEORGE DEWOLF 1903 - 2000 HOMETOWN HERO HÉROS DE CHEZ NOUS Born in Bedford, Nova Scotia, Harry DeWolf developed a passion for Originaire de Bedford en Nouvelle-Écosse, Harry DeWolf se passionne pour the sea as a youth by sailing in Halifax Harbour and Bedford Basin, later la mer dès sa jeunesse en naviguant dans le port d’Halifax et le bassin de pursuing a 42-year career in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). Bedford, ce qui l’amènera à poursuivre une carrière de 42 ans au sein de la Marine royale du Canada (MRC). During the Second World War, he earned a reputation as a skilled, courageous officer. As captain of HMCS St Laurent, in 1940 DeWolf Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il se fait une réputation d’officier ordered the RCN’s first shots fired during the early stages of the war. de marine compétent et courageux. À la barre du NCSM St Laurent en CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military© Image Museum 2011.022.012 courtesy of the Beament collection, © Image Collection Beanment 2011.022.012 avec l’aimable autorisation du Musée naval et militaire de la BFC Esquimalt, He led one of the largest rescues when his ship saved more than 850 1940, DeWolf ordonne les premiers tirs de la MRC au début de la guerre. -

The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2020 A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983 Garison Ma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Political History Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Ma, Garison, "A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983" (2020). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 2330. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983 by Garison Ma BA History, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2018 THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of History in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Master of Arts in History Wilfrid Laurier University © Garison Ma 2020 To my parents, Gary and Eppie and my little brother, Edgar. II Abstract In December 1977, the Liberal government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau authorized the Department of National Defence (DND) to begin the acquisition of new warships for the navy. The decision to acquire fully combat capable warships was a shocking decision which marked the conclusion of a remarkable turnaround in Canadian defence policy. -

Capable Arctic Offshore Patrol Ship NOPEC

VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3 (2015) The Case for a More Combat- Capable Arctic Offshore Patrol Ship NOPEC: A Game Worth Playing? Interoperability and the Future of the Royal Canadian Navy A Clash of Naval Strategies in the Asia-Pacific Region VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3 (2015) CANADIAN NAVAL REVIEW I Winter_2015_PRESS.indd 1 15-01-26 1:46 PM Our Sponsors and Supporters Canadian Naval Review (CNR) is a ‘not-for-profit’ corporate support CNR would not be able to maintain publication depending for funding upon its subscription its content diversity and its high quality. Corporate and base, the generosity of a small number of corporate institutional support also makes it possible to put copies sponsors, and support from the Department of National of CNR in the hands of Canadian political decision- Defence and the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies at makers. The help of all our supporters allows CNR to Dalhousie University. In addition, CNR is helped in continue the extensive outreach program established to meeting its objectives through the support of several further public awareness of naval and maritime security professional and charitable organizations. Without that and oceans issues in Canada. (www.canadasnavalmemorial.ca) (www.navyleague.ca) Naval Association of Canada (www.navalassoc.ca) To receive more information about the corporate sponsorship plan or to find out more about supporting CNR in other ways, such as through subscription donations and bulk institutional subscriptions, please contact us at [email protected]. i CANADIAN NAVAL REVIEW VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3 (2015) Winter_2015_PRESS.indd 1 15-01-26 1:46 PM Cpl Services Bastien, Imaging Credit: Services MARPAC Michael MARPAC Imaging Our Sponsors and Supporters VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3 (2015) Bastien, Editorial Board Dr. -

LABARGE, Raymond Clement, Lieutenant-Commander

' L ' LABARGE, Raymond Clement, Lieutenant-Commander (SB) - Member - Order of the British Empire (MBE) - RCNVR / Deputy Director of Special Services - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 5 January 1946 and London Gazette of 1 January 1946. Home: Ottawa, Ontario. LABARGE. Raymond Clement , 0-39790, Lt(SB)(Temp) [19.10.42] LCdr(SB)(Temp) [1.1.45] Demobilized [1.12.45] MBE ~[5.1.46] "Lieutenant-Commander Labarge, as Deputy Director of Special Services, has contributed greatly to the welfare of the Canadian Naval Service. Through his zeal, energy and tact, recreational facilities and comforts were successfully distributed to ships at sea and to Shore Establishments at home and Overseas, thus aiding in a great measure to keep up the high morale of Naval personnel." * * * * * * LABELLE, Rowel Joseph, Petty Officer Telegraphist (V-6282) - Mention in Despatches - RCNVR - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 6 January 1945 and London Gazette of 1 January 1945. Home: Ottawa, Ontario. LABELLE. Rowel Joseph , V-6282, PO/Tel, RCNVR, MID ~[6.1.45] "As Senior Telegraphist rating on the staff of an ocean escort group, this rating has by his keen, cheerful leadership in the training of communication ratings of the ships of the group, been largely responsible for maintaining the efficiency of the communications at a consistently high level." * * * * * * LA COUVEE, Reginald James, Commissioned Engineer - Member - Order of the British Empire (MBE) - RCNR - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 9 January 1943 and London Gazette of 1 January 1943. Home: Vancouver, British Columbia. La COUVEE. Reginald James , 0-39820, A/Wt(E)(Temp) [15.7.40] RCNR HMCS PRINCE HENRY (F70) amc, stand by, (2.9.40-3.12.40) HMCS PRINCE HENRY (F70) amc, (4.12.40-?) Lt(E)(Temp) [1.1.43] HMCS PRINCE ROBERT (F56) a/a ship, (2.2.43-?) MBE ~[9.1.43] Lt(E)(Temp) [1.1.42] HMCS WOLF (Z16)(P) p/v, (2.1.45-?) Demobilized [27.10.45] "Whilst serving in one of HMC Auxiliary Cruisers over a considerable period of time, Mr. -

The Case for Canadian Naval Ballistic Missile Defence Mahan And

VOLUME 14, NUMBER 3 (2019) Winner of the 2018 CNMT Essay Competition The Case for Canadian Naval Ballistic Missile Defence Mahan and Understanding the Future of Naval Competition in the Arctic Ocean China’s Arctic Policy and its Potential Impact on Canada’s Arctic Security Technology and Growth: The RCN During the Battle of the Atlantic Our Sponsors and Supporters Canadian Naval Review (CNR) is a ‘not-for-profi t’ pub- not be able to maintain its content diversity and its high lication depending for funding upon its subscription base, quality. Corporate and institutional support also makes the generosity of a small number of corporate sponsors, it possible to put copies of CNR in the hands of Canadian and support from the Department of National Defence. political decision-makers. Th e help of all our supporters In addition, CNR is helped in meeting its objectives allows CNR to continue the extensive outreach program through the support of several professional and charitable established to further public awareness of naval and organizations. Without that corporate support CNR would maritime security and oceans issues in Canada. (www.navalassoc.ca) (www.canadasnavalmemorial.ca) (www.navyleague.ca) To receive more information about the corporate sponsorship plan or to fi nd out more about supporting CNR in other ways, such as through subscription donations and bulk institutional subscriptions, please contact us at [email protected]. i CANADIAN NAVAL REVIEW VOLUME 14, NUMBER 3 (2019) VOLUME 14, NO. 3 (2019) Editorial Board Dr. Andrea Charron, Tim Choi, Vice-Admiral (Ret’d) Gary Credit: Cpl Donna McDonald Garnett, Dr. -

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 72, Autumn 2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… The Kingston-class Maritime Coastal Defence Vessel (MCDV) HMCS Whitehorse conducts maneuverability exercises off the west coast. NAVAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA ASSOCIATION NAVALE DU CANADA (See: “One Navy and the Naval Reserve” beginning on page 9.) Royal Canadian Navy photo. Starshell ISSN-1191-1166 In this edition… National magazine of the Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada From the Editor 4 www.navalassoc.ca From the Front Desk 4 PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh NAC Regalia Sales 5 HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele From the Bridge 6 PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] Maritime Affairs: “Another Step Forward” 8 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] One Navy and Naval Reserve 9 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] NORPLOY ‘74 12 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] Mail Call 18 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. Alec Douglas, [email protected] The Briefing Room 18 HONORARY COUNSEL • Donald Grant, [email protected] Schober’s Quiz #69 20 ARCHIVIST • Fred Herrndorf, [email protected] This Will Have to Do – Part 9 – RAdm Welland’s Memoirs 20 AUSN LIAISON • Fred F. -

HMCS Chicoutimi

Submariners Association of Canada-West Newsletter Angles & Dangles HMCS Chicoutimi www.saocwest.ca SAOC-WEST www .saocwest.ca Fall 2020 Page 2 IN THIS ISSUE: Page 1 Cover HMCS Chicoutimi Page 2 Index President Page 3 From the Bridge Report Wade Berglund 778-425-2936 Page 4 HMCS Chicoutimi [email protected] Page 5-6 RCN Submariners Receive Metals Page 7 -8 China’s Submarines Can Now Launch A Nuclear War Against America Page 9-10 Regan Carrier Strike Group Vice-President Patrick Hunt Page 11-12 US, Japan, Australia Team Up 250-213-1358 [email protected] Page 13-14 China’s Strategic Interest in the Artic Page 15 Royal Navy Officer ‘Sent Home” Page 16-17 Watch a Drone Supply Secretary Page 18-20 Cdn Navy Enters New Era Warship Lloyd Barnes 250-658-4746 Page 21-23 Are Chinese Submarines Coming [email protected] Page 24-25 Lithium-ion Batteries Page 26 A Submariner’s Perspective Page 27-28 Iran’s New Submarine Debuts Treasurer & Membership Page 29 Media-Books Chris Parkes 250-658-2249 Page 30 VJ Day– Japan 1945 Chris [email protected] Page 31 Priest Sent To Prison Page 32 Award Presentation Page 33 Eternal Patrol Page 34 Below Deck’s & Lest We Forget Angles & Dangles Newsletter Editor Valerie Brauschweig [email protected] The SAOC-W newsletter is produced with acknowledgement & appreciation to the authors of articles, writers and photographers, Cover Photo: stories submitted and photos sourced . HMCS Chicoutimi Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of SAOC-W. Fall 2020 SAOC-WEST Page 3 review the Constitution and Bylaws, and a decision as The Voice Pipe to holding member meetings was made. -

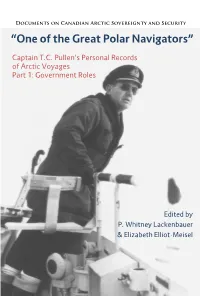

"One of the Great Polar Navigators": Captain T.C. Pullen's Personal

Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security “One of the Great Polar Navigators” Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages Part 1: Government Roles Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer & Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security (DCASS) ISSN 2368-4569 Series Editors: P. Whitney Lackenbauer Adam Lajeunesse Managing Editor: Ryan Dean “One of the Great Polar Navigators”: Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages, Volume 1: Official Roles P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel DCASS Number 12, 2018 Cover: Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage, BIOG P: Pullen, Thomas Charles, file 2004/55, folder 1. Cover design: Whitney Lackenbauer Centre for Military, Security and Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Strategic Studies St. Jerome’s University University of Calgary 290 Westmount Road N. 2500 University Dr. N.W. Waterloo, ON N2L 3G3 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 519.884.8110 ext. 28233 Tel: 403.220.4030 www.sju.ca/cfpf www.cmss.ucalgary.ca Arctic Institute of North America University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW, ES-1040 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403-220-7515 http://arctic.ucalgary.ca/ Copyright © the authors/editors, 2018 Permission policies are outlined on our website http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/research/arctic-document-series “One of the Great Polar Navigators”: Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages Volume 1: Official Roles P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. and Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel, Ph.D. Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. i Acronyms ............................................................................................................... xlv Part 1: H.M.C.S. -

UNTDA-UC Newsletter V03

SPRING EDITION MARCH 2001 EDITOR Robert Williamson ISSN 1480 - 0470 Being university students, UNTiIDies could at one moment be the model of intelligent dedication and naval discipline, or play silly tricks as a measure of disrespect for authority. This cadet squad at HMCS Stadacona in 1955 is “Dressing by the right” or Undressing as the case may be. The exposed cadet in the rear rank did not stay the course, although his twin brother received his navy commission and became a Medical Photo courtesy Lt, P Neroutsos, OStJ, CD, RCNR (Ret.), Victoria, Doctor. UNTD Assoc Newsletter - 2001 March - page 1 of 12 NAVAL HISTORIAN - SPEAKER Congratulations to Bob Willson and the UNTD At Eleventh Annual UNTD Reunion Dinner Association for continuing to provide high caliber and memorable Reunion Mess Dinner Forty-five former UNTDs assembled in the speakers. We can look forward to next year’s Wardroom of HMCS YORK on Saturday evening reunion dinner, which will follow a Dine Your November 18, 2000. Some guests had traveled Sweetheart format with a mystery V.1.P. speaker from as far away as Calgary and Missouri to that might be a woman. Jack Kilgour / Editor attend this eleventh annual event. The first dinner was held at the Canadian Forces Staff Editors Note College in 1989. For those diners who would like to recall Norm Balfour's memorable dinner performance and for he Bob Willson, the President of the dinner ran a the benefit of those who could not be there, well organized program and invited diners to has written out the words to “Please Oblige Us participate by sharing their favorite song or With A Bren Gun,” by Noel Coward. -

Welcome to HMC Dockyard the First Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS), HMCS Harry Dewolf, Was Delivered to the Government of Canada on July 31, 2020, in Halifax

Monday August 10, 2020 Volume 54, Issue 16 www.tridentnewspaper.com Welcome to HMC Dockyard The first Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS), HMCS Harry DeWolf, was delivered to the Government of Canada on July 31, 2020, in Halifax. This is an historic milestone for the RCN, as it is the first ship in the largest fleet recapitalization in Canada’s peacetime history. MONA GHIZ, MARLANT PA 2 TRIDENT NEWS AUGUST 10, 2020 Members of HMCS Harry DeWolf formed up on the new jetty at HMC Dockyard before boarding their ship for the first time. MONA GHIZ, MARLANT PA Next generation of RCN ships begins with delivery of HMCS Harry DeWolf By Ryan Melanson, Trident Staff The Royal Canadian Navy’s Arc- in an age of profound climate change. various small vehicles and deployable on board, and will continue working tic and Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS) As these ships begin getting delivered, multi-role rescue boats and landing with simulators to get accustomed to program, as well as the wider National there will be much work for them to craft that are new to the RCN. The the new integrated bridge system, all Shipbuilding Strategy, has reached its do.” class also brings new technology in while preparing to go to sea. Harry De- most significant milestone yet. HMCS In addition to the first crew of Harry the way of weapons, firefighting sys- Wolf’s first sail will be a short 10-day Harry DeWolf, the first ship of the DeWolf and Navy leadership, the deliv- tems, and bridge integration, meaning training mission in the local area. -

Circumpolar Military Facilities of the Arctic Five

CIRCUMPOLAR MILITARY FACILITIES OF THE ARCTIC FIVE Ernie Regehr, O.C. Senior Fellow in Arctic Security and Defence The Simons Foundation Canada and Michelle Jackett, M.A. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Circumpolar Military Facilities of the Arctic Five – updated: July 2018 Ernie Regehr, O.C., and Michelle Jackett, M.A. Circumpolar Military Facilities of the Arctic Five Introduction This compilation of current military facilities in the circumpolar region1 continues to be offered as an aid to addressing a key question posed by the Canadian Senate more than five years ago: “Is the [Arctic] region again becoming militarized?”2 If anything, that question has become more interesting and relevant in the intervening years, with commentators divided on the meaning of the demonstrably accelerated military developments in the Arctic – some arguing that they are primarily a reflection of increasing military responsibilities in aiding civil authorities in surveillance and search and rescue, some noting that Russia’s increasing military presence is consistent with its need to respond to increased risks of things like illegal resource extraction, terrorism, and disasters along its frontier and the northern sea route, and others warning that the Arctic could indeed be headed once again for direct strategic confrontation.3 While a simple listing of military bases, facilities, and equipment, either based