A HISTORY of GARRISON CALGARY and the MILITARY MUSEUMS of CALGARY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

Cover: During World War I, convoys carried almost two million men to Europe. In this 1920 oil painting “A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole, the destroyer USS Allen (DD-66) is shown escorting USS Leviathan (SP-1326). Throughout the course of the war, Leviathan transported more than 98,000 troops. Naval History and Heritage Command 1 United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922 Frank A. Blazich Jr., PhD Naval History and Heritage Command Introduction This document is intended to provide readers with a chronological progression of the activities of the United States Navy and its involvement with World War I as an outside observer, active participant, and victor engaged in the war’s lingering effects in the postwar period. The document is not a comprehensive timeline of every action, policy decision, or ship movement. What is provided is a glimpse into how the 20th century’s first global conflict influenced the Navy and its evolution throughout the conflict and the immediate aftermath. The source base is predominately composed of the published records of the Navy and the primary materials gathered under the supervision of Captain Dudley Knox in the Historical Section in the Office of Naval Records and Library. A thorough chronology remains to be written on the Navy’s actions in regard to World War I. The nationality of all vessels, unless otherwise listed, is the United States. All errors and omissions are solely those of the author. Table of Contents 1914..................................................................................................................................................1 -

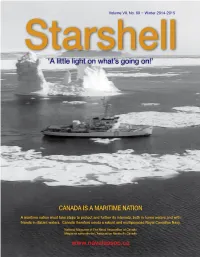

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 69 ~ Winter 2014-2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… To date, the Royal Canadian Navy’s only purpose-built, ice-capable Arctic Patrol Vessel, HMCS Labrador, commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy July 8th, 1954, ‘poses’ in her frozen natural element, date unknown. She was a state-of-the- Starshell art diesel electric icebreaker similar in design to the US Coast Guard’s Wind-class ISSN-1191-1166 icebreakers, however, was modified to include a suite of scientific instruments so it could serve as an exploration vessel rather than a warship like the American Coast National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Guard vessels. She was the first ship to circumnavigate North America when, in Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada 1954, she transited the Northwest Passage and returned to Halifax through the Panama Canal. When DND decided to reduce spending by cancelling the Arctic patrols, Labrador was transferred to the Department of Transport becoming the www.navalassoc.ca CGSS Labrador until being paid off and sold for scrap in 1987. Royal Canadian Navy photo/University of Calgary PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele In this edition… PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] NAC Conference – Canada’s Third Ocean 3 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] The Editor’s Desk 4 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] The Bridge 4 The Front Desk 6 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] NAC Regalia Sales 6 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

The Trade Journal Newsletter Editor the Older You Get, the More Important Hon

DS T H E T R A D E 257 JOURNAL 9 Derbyshire Submariners Newsletter Issue Number 257 March 2021 Freedom of the City of Derby to RN Submarine Service Granted 28 April 2002 Page/s Subject EDITORIAL 01 CONTENT & EDITORIAL Sad that Anzac Day, the Australian equivalent of 02 WELFARE our Remembrance Sunday has had to be severely scaled down due to CV, and also that in this country 03/04 POLITICALLY INCORRECT PAGES major events for July-Sept are 05 JEFF BACON © TWO TIFFS also being ‘pulled’. We have 06 WIDOW OF WWI S/M VC OBITUARY been advised the Spring Notts Vets meeting is cancelled and I 07 COMAUSSUBRON ONE REMEMBERED am awaiting the thoughts on 08 K13 & CREW REMEMBERED 2021 Stanley Bomber Memorial on 3 09-10 HMS URGE LOCATION CLAIMS July which may have to be postponed until the 60th 11 SPEARFISH TORPEDOS CONTRACT Anniversary in 2022? Sorry, I 12 USA & ASIA SUBMARINE NEWS could not give a damn about not 13 WAR WIDOWS OFFER COOK BOOK being able to have a summer holiday this year, as I believe more important things in life matter more, 14 RARE MAPS & QEII DESIG FLAG namely loved ones staying safe, and also my many 15 GENERAL WELFARE TOPICS friends both in this country and abroad matters 16 WORLD UNDERWATER NEWS more. I feel justified in saying this having been confined at home since 3 Dec 2019 as prior to 17-18 BZ AMBUSH + S/M DIVISION NL Lockdown1 I was confined to home in recuperation 19 NEWSLETTER FEEDBACK / RNBT following surgery! At the time of the release of this 20 TRAF MEDICAL CHEST / S/M NEWS newsletter I will have had my Covid jab and from members reports now progressing into the 60+ age 21 FASLANE PORN / HMS TALENT NEWS bracket. -

HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and Life in the West Coast Reserve Fleet, 1913-1918

Canadian Military History Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 2 2010 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Richard O. Mayne "“For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918." Canadian Military History 19, 1 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne n 30 October 1918, Arthur for all activities related to Canada’s Ashdown Green, a wireless Abstract: HMCS Galiano is remembered oceans and inland waters including O mainly for being the Royal Canadian operator on Triangle Island, British Navy’s only loss during the First World the maintenance of navigation Columbia, received a bone-chilling War. However, a close examination aids, enforcement of regulations signal from a foundering ship. of this ship’s history not only reveals and the upkeep of hydrographical “Hold’s full of water,” Michael John important insights into the origins and requirements. Protecting Canadian identity of the West Coast’s seagoing Neary, the ship’s wireless operator sovereignty and fisheries was also naval reserve, but also the hazards and desperately transmitted, “For God’s navigational challenges that confronted one of the department’s key roles, Sake send help.” Nothing further the men who served in these waters. -

1 ' F ' FAFARD, Charles Omar, Signalman (V-4147)

' F ' FAFARD, Charles Omar, Signalman (V-4147) - Mention in Despatches - RCNVR / HMCS Columbia - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 29 May 1943 and London Gazette of 5 October 1943. Home: Montreal, Quebec HMCS Columbia was a Town Class Destroyer (I49) (ex-USS Haraden) FAFARD. Charles Omar, V-4147, Sigmn, RCNVR, MID~[29.5.43] "This rating showed devotion to duty and was alert, cheerful and resourceful when performing duties in connection with the salvaging of S.S. Matthew Luckenbach. "For good services in connection with the salvage of S.S. Matthew Luckenbach while serving in HMCS Columbia (London Gazette)." * * * * * * 1 FAHRNI, Gordon Paton, Surgeon Lieutenant - Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) - RCNVR / HMS Fitzroy - Awarded as per London Gazette of 30 July 1942 (no Canada Gazette). Home: Winnipeg, Manitoba. Medical Graduate of the University of Manitoba in 1940. He earned his Fellowship (FRCS) in Surgery after the war and was a general surgeon at the Winnipeg General and the Winnipeg Children’s Hospitals. FAHRNI. Gordon Paton, 0-22780, Surg/LCdr(Temp) [7.10.39] RCNVR DSC~[30.7.42] Surg/LCdr [14.1.47] RCN(R) HMCS CHIPPAWA Winnipeg Naval Division, (25.5.48-?) Surg/Cdr [1.1.51] "For great bravery and devotion to duty. For great gallantry, daring and skill in the attack on the German Naval Base at St. Nazaire." HMS Fitzroy (J03 - Hunt Class Minesweeper) was sunk on 27 May 1942 by a mine 40 miles north-east of Great Yarmouth in position 52.39N, 2.46E. It was most likely sunk by a British mine! It had been commissioned on 01 July 1919. -

Ahoy Shipmate RNA Torbay Newsletter

Ahoy Shipmate RNA Torbay Newsletter Volume 4 Issue 3 May 2015 In this issue Editorial Editorial ................................ 1 By Shipmate Norrie Millen Chairman’s Corner .................. 2 Hi! Shipmates, Stuffed Shirt Attitude .............. 2 RNA Welfare Seminar .......... 3 -4 I am completely fed up; as indeed I know you all Cooks to the galley ................. 5 are, with Torbay Councils decision not to China Fleet Club Part 3 ........ 6 -9 include or invite us to participate in the HM S/M Torbay - Freedom 10 -11 Freedom of Torbay granted to submarine crew President’s Patter .................. 11 of HM S/M Torbay. Given the fact, we are the Silke’s Story ................... 12 -14 only naval association in Torbay (unless you US Navy’s Laser Weapon ........ 15 include RNA Brixham) and our close liaison with the submarine begs the question “What Back and forth . were they thinking?” or were they thinking at all! Back and forth . Speaking to some of our members, I can fully understand the In and out . frustration and anger this has caused and I personally do not intend to let the matter rest. My major shortcoming is I have low In and out . diplomatic skills and prefer to call a spade a shovel. You might A little to the right. say I am one-faced! A little to the left . The most important point though is that we have missed a She could feel the sweat on her massive golden opportunity to broadcast our presence and the forehead . Down her chest. chance for some free PR and recruiting advertising. Wouldn’t it have been nice to form up at the end of march with our Branch And, trickling down the small of her back . -

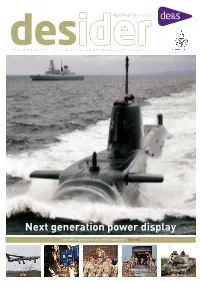

Next Generation Power Display

Apr/May 10 Issue 24 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Next generation power display Latest DE&S organisation chart and PACE supplement See inside Parc Chain Dress for Welcome Keeping life gang success home on track Picture: BAE Systems NEWS 5 4 Keeping on track Armoured vehicles in Afghanistan will be kept on track after DE&S extended the contract to provide metal tracks the vehicles run on. 8 UK Apache proves its worth The UK Apache attack helicopter fleet has reached the landmark of 20,000 flying hours in support of Operation Herrick 8 Just what the doctor ordered! DE&S’ Chief Operating Officer has visited the 2010 y Nimrod MRA4 programme at Woodford and has A given the aircraft the thumbs up after a flight. /M 13 Triumph makes T-boat history The final refit and refuel on a Trafalgar class nuclear submarine has been completed in Devonport, a pril four-year programme of work costing £300 million. A 17 Transport will make UK forces agile New equipment trailers are ready for tank transporter units on the front line to enable tracked vehicles to cope better with difficult terrain. 20 Enhancement to a soldier’s ‘black bag’ Troops in Afghanistan will receive a boost to their personal kit this spring with the introduction of cover image innovative quick-drying towels and head torches. 22 New system is now operational Astute and Dauntless, two of the most advanced naval A new command system which is central to the ship’s fighting capability against all kinds of threats vessels in the world, are pictured together for the first time is now operational on a Royal Navy Type 23 frigate. -

Official Lineages, Volume 2, Part 1: Extant Commissioned Ships

A-AD-267-000/AF-002 THE INSIGNIA AND LINEAGES OF THE CANADIAN FORCES Volume 2, Part 1 EXTANT COMMISSIONED SHIPS LES INSIGNES ET LIGNÉES DES FORCES CANADIENNES Tome2,Partie1 NAVIRES MIS EN SERVICE EXISTANT ENCORE A CANADIAN FORCES HERITAGE PUBLICATION UNE PUBLICATION DU PATRIMOINE DES FORCES CANADIENNES National Défense A-AD-267-000/AF-002 Defence nationale THE INSIGNIA AND LINEAGES OF THE CANADIAN FORCES VOLUME 2, PART 1 – EXTANT COMMISSIONED SHIPS (BILINGUAL) (Supersedes A-AD-267-000/AF-000 dated 1975-09-23) LES INSIGNES ET LIGNÉES DES FORCES CANADIENNES TOME 2, PARTIE 1 – NAVIRES MIS EN SERVICE EXISTANT ENCORE (BILINGUE) (Remplace l’A-AD-267-000/AF-000 de 1975-09-23) Issued on Authority of the Chief of the Defence Staff Publiée avec l’autorisation du Chef d’état-major de la Défense OPI: DHH BPR : DHP 2001-01-08 Canada A-AD-267-000/AF-002 LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES ÉTAT DES PAGES EN VIGUEUR Insert latest changed pages, dispose of superseded Insérer les pages le plus récemment modifiées et pages with applicable orders. disposer de celles qu'elles remplacent conformément aux instructions applicables. NOTE NOTA The portion of the text affected by the latest La partie du texte touchée par le plus récent change is indicated by a black vertical line in modificatif est indiquée par une ligne verticale the margin of the page. Changes to dans la marge. Les modifications aux illustrations are indicated by miniature pointing illustrations sont indiquées par des mains hands or black vertical lines. miniatures à l'index pointé ou des lignes verticales noires. -

In Peril on the Sea – Episode Two Chapter 1Part 1

In Peril on the Sea – Episode Two Chapter 1Part 1 CANADA AND THE SEA: 1600 - 1918 Flagship of the Fleet: The Old "Nobbler" An armoured cruiser, HMCS Niobe was commissioned in the RN in 1898 and transferred to the infant Canadian Naval Service in 1910. She displaced 11,000 tons, carried a crew of 677 and was armed with sixteen 6-inch guns, twelve 12-pdr. guns, five 3-pdr. quick-firing guns and two 18-inch torpedo tubes. Despite the British penchant for naming major warships after dis- tinguished admirals or figures from classical mythology, sailors had their own, much less glamorous, nicknames for their vessels and Niobe was always "Nobbler" to her crew. Niobe served until 1920 when she was sold for scrap. (Courtesy, National Archives of Canada, PA 177136) At sea, Sunday, 13 September 1942 The burial service took place on the quarterdeck just before sunset. The sky was overcast with a definite threat of rain but only a moderate sea was running and the wind force was just 3 or about 10 miles per hour. All members of the crew of the destroyer HMCS Ottawa not on watch were in at- tendance in pusser rig, their best dress, although the commanding -officer, Lieutenant Commander Clark Rutherford, RCN, remained on the bridge. The convoy he was escorting, ON 127 out of Lough Foyle in Ireland bound for Halifax, had lost seven merchantmen in the last three days, and though the arrival of air cover from Newfoundland that morning was cause for optimism, the danger was far from over. -

HMCS Prince Henry (Ex-North Star) Escapes the St Lawrence Before Freeze-Up 1940

CHAPTER 8 HMCS Prince Henry (ex-North Star) escapes the St Lawrence before freeze-up 1940 CLARKE SHIPS GO TO WAR - AND WAR COMES TO THE ST LAWRENCE On Friday, September 1, 1939, the North Star, was in the middle of her final cruise of the summer, from New York to Montreal, at Bonne Bay, Newfoundland. The New Northland, on her sixth cruise of the season, was in the "Kingdom of the Saguenay." Both are places of great beauty. Passengers looked forward to a calm and peaceful day, but the news from Europe was anything but that. Germany had just invaded Poland. Two days later, on Sunday, September 3, with Germany having ignored a deadline set by the United Kingdom and France to withdraw from Poland, the world would be at war. On the day that war was declared, Donaldson Line's Athenia was a day out from Liverpool, en route from Glasgow to Montreal by way of the Strait of Belle Isle. But she would never reach Canada. Instead, she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-30, whose captain supposedly mistook her for a warship. Some 118 lives were lost in this, the first Allied merchant ship loss of the war. Luckily, conditions allowed 1,300 survivors to be rescued by two cargo ships, one American and one Norwegian, the Swedish yacht Southern Cross and the British destroyers HMS Electra, Escort and Fame. The 5,749- ton Knute Nelson landed 449 survivors at Galway Bay in Ireland, while the Southern Cross rescued 376 and transferred 236 of them to the 4,963-ton City of Flint, which took them on to Halifax. -

Rnshs Virtual Plaque Series: H.M.C.S

RNSHS VIRTUAL PLAQUE SERIES: H.M.C.S. NIOBE’S ARRIVAL IN HALIFAX 1910 1 H.M.C.S. NIOBE’S ARRIVAL IN HALIFAX, 21 OCTOBER 1910 Through the first three decades after Confederation most Canadians assumed that they had no need of a navy of their own. With their Arctic waters safeguarded by ice and the Atlantic and Pacific coasts patrolled by vessels of the Royal Navy, Canada could concentrate on such land-based objectives as settlement of the prairie West and development of an urban-industrial core elsewhere. The only exception to this inward-looking orientation was provided by the Department of Marine and Fisheries (DMF), which operated several inshore patrol vessels designated to protect Canadian fishing grounds from American encroachment and also maintain the lighthouses and other aids to navigation strung along both our salt and fresh water shores. The decisive factor transforming benign neglect into vigorous self-assertion with respect to naval matters was the shifting balance of power at sea in Europe. By 1902 British assumptions about their capacity to maintain that nation’s status as the world’s preeminent naval power were in retreat. Con- struction of ever more formidable high seas fleets by the United States, Japan and especially Germany, forced the London government to reassess its naval strategy. In 1906 fleet consolidation in home waters brought about the abandonment of Halifax as an imperial military base and led to virtual elimi- nation of the Royal Navy’s peacetime presence in Canadian waters. Admiralty planners, despairing of Canadian assistance, had begun to assume that if war broke out protection of the sea approaches to Canada would have to be assigned to vessels of the American and Japanese navies. -

Crowsnest Issue 4-2.Qxd

Special Navy Centennial Issue CCrroowwssnneesstt Vol. 4, No. 2 Summer 2010 Chief of the Maritime Staff Sailors march through the streets of Halifax during a Freedom of the City parade May 4. NNaavvyy cceelleebbrraatteess 110000 yyeeaarrss ooff pprroouudd sseerrvviiccee Photo: Cpl Rick Ayer INSIDE HMCS Fredericton Reservists make home from dive history in THIS overseas mission the North ISSUE PAGE 10 PAGE 12 www.navy.forces.gc.ca Committing to the next 100 years he navy is now 100 years old. Under the authority of the Naval Services Act, the T Canadian Naval Service was created May 4, 1910. In August 1911 it was designated the Royal Canadian Navy by King George V until 1968 when it became Maritime Command within the Canadian Armed Forces. During the navy’s first century of service, Canada sent 850 warships to sea under a naval ensign. To mark the navy’s 100th anniversary, Canadian Naval Centennial (CNC) teams in Halifax, Ottawa, Esquimalt, 24 Naval Reserve Divisions across the Photo: MCpl Serge Tremblay country, and friends of the navy created an exciting Chief of the Maritime Staff Vice-Admiral Dean McFadden, program of national, regional and local events with left; Marie Lemay, Chief Executive Officer of the National the goal of bringing the navy to Canadians. Many of Capital Commission (NCC); and Russell Mills, Chair of these events culminated May 4, 100 years to the day the NCC’s Board of Directors, participate in a sod-turning that Canada’s navy was born. ceremony May 4 for the Canadian Navy Monument to be The centennial slogan, “Commemorate, Celebrate, built at Richmond Landing behind Library and Archives Commit”, reflects on a century of proud history, the Canada on the Ottawa River.