Civic Genealogy from Brunetto to Dante

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Hell of a City: Dante's Inferno on the Road to Rome ([email protected]) DANTE's WORKS Rime (Rhymes): D.'S Lyrical Poems, Cons

A Hell of a City: Dante’s Inferno on the Road to Rome ([email protected]) DANTE’S WORKS Rime (Rhymes): D.'s lyrical poems, consisting of sonnets, canzoni, ballate, and sestine, written between 1283 [?] and 1308 [?]. A large proportion of these belong to the Vita Nuova, and a few to the Convivio; the rest appear to be independent pieces, though the rime petrose (or “stony poems,” Rime c-ciii), so called from the frequent recurrence in them of the word pietra, form a special group, as does the six sonnet tenzone with Forese Donati: http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp/rime.html (Testo critico della Societa' Dantesca Italiana; Florence: Societa' Dantesca Italiana, 1960. Edited by Michele Barbi. Translated by K. Foster and P. Boyde.) Vita nova (The New Life): Thirty-one of Dante's lyrics surrounded by an unprecedented self-commentary forming a narrative of his love for Beatrice (1293?). D.'s New Life, i.e. according to some his 'young life', but more probably his 'life made new' by his love for Beatrice. The work is written in Italian, partly in prose partly in verse (prosimetron), the prose text being a vehicle for the introduction, the narrative of his love story, and the interpretation of the poems. The work features 25 sonnets (of which 2 are irregular), 5 canzoni (2 of which are imperfect), and 1 ballata: http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp/vnuova.html (Testo critico della Società Dantesca Italiana; Florence: Società Dantesca Italiana, 1960. Edited by Michele Barbi. Translated by Mark Musa.) In the Vita Nuova, which is addressed to his 'first friend', Guido Cavalcanti, D. -

The Political Persecution of a Poet: a Detail of Dante's Exile

Parkland College A with Honors Projects Honors Program 2012 The olitP ical Persecution of a Poet: A Detail of Dante's Exile Jason Ader Parkland College Recommended Citation Ader, Jason, "The oP litical Persecution of a Poet: A Detail of Dante's Exile" (2012). A with Honors Projects. 44. http://spark.parkland.edu/ah/44 Open access to this Article is brought to you by Parkland College's institutional repository, SPARK: Scholarship at Parkland. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICAL PERSECUTION OF A POET A Detail of Dante's Exile By Jason Ader John Poling History 101 April 2012 Durante degli Alighieri, known throughout the world as simply Dante, was a fourteenth century Italian poet, philosopher, literary theorist, and politician. He is best known for his epic Commedia, which was later dubbed The Divine Comedy. Commedia is generally considered the greatest Italian literary work and a masterpiece of world literature.1 Due to the turbulent political atmosphere of his time and place, Dante spent over a third of his life living in exile. This paper will explore the details of Dante's exile and the influence that it had upon his work. Dante was born in Florence around 1265 to an aristocratic family of moderate wealth and status. Dante's father was a notary, and Dante was the only child of his father's first marriage. Dante's mother died when he was about thirteen years old. His father then remarried and his second wife bore another son and two daughters before he too died when Dante was about eighteen.2 It is thought that at around six years of age Dante entered school. -

II EDIZIONE Bambini E Gli Adolescenti Come “Individui”

Con il patrocinio di La data ricorda il giorno in cui l' Assemblea Partecipano al Progetto In collaborazione con la Commizssione 7 Generale delle Nazioni Unite adottò, nel 1989, di Firenze la convenzione ONU sui diritti dell'infanzia e dell'adolescenza. In collaborazione con Con il contributo di La “Carta dei Diritti del Bambino” fu scritta già nel 1923 da Eglantyne Jebb, dama della Croce Rossa. Ancora oggi molti sono i bambini e gli adolescenti, anche in Italia, vittime di violenza, abusi, discriminazioni, che vivono situazioni di trascuratezza sociale – psicologica nonché scolastica e culturale. Tutti abbiamo il dovere di prendere coscienza dell'importanza di trattare i II EDIZIONE bambini e gli adolescenti come “individui”. Il tema Giornata Mondiale è particolarmente sentito dagli Artisti Fiesolani che operano affinché “l'Arte e la Cultura” possano dei Diritti dell'Infanzia mantenere il primato tra le attività umane. e dell'Adolescenza Artisti in esposizione: Fiamma Antoni Ciotti Irina Meniailova Mariangela Bartoloni Valerio Mirannalti Francesco Beccastrini Lorenzo Montagni Stefania Biagioni Susanna Pellegrini Istituto Comprensivo “Coverciano” Via Salvi Cristiani, 3 – 50135 Firenze Fernando Cardenas Scuola Primaria S.Maria a Coverciano Francesco Perna Barbara Cascini Puccio Pucci Alessandro Ciappi COMUNE DI GAMBASSI TERME ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO STATALE Matteo Rimi E DI MONTAIONE “Ernesto BALDUCCI” Roberto Coccoloni Mariadonata Sirleo Andrea Sole Costa Roberto D’Angelo Sanja Spasic Laura Felici Paola Stazzoni Alessandro Goggioli Sara -

[email protected] [email protected] NUMERI UTILI / / UTILI NUMERI User Numbers User

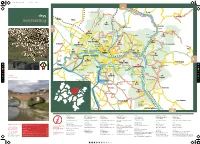

A3-Map-Pontassieve.pdf 1 03/12/19 19:24 ✟ CONVENTO ✟ PIEVE DI S. GIOVANNI MAGGIORE di Bilancino DI BOSCO AI FRATI Villore CAFAGGIOLO Borgo S. Lorenzo BOLOGNA Le Croci di Calenzano Vicchio Map S. Godenzo Pontassieve Agliana PRATO A1 Legri Vaglia CONVENTO Dicomano PISA DI MONTE SENARIO Frascole Rincine Pratolino Contea Calenzano Olmo Acone VILLA DEMIDOFF S. Brigida Cercina Londa A11 Colonnata Scopeti Capalle LA PETRAIA Caldine Sesto Fiorentino CASTELLO Monteloro Pomino Carmignano ✟ PIEVE DI S. BARTOLOMEO Campi Bisenzio AEROPORTO Fiesole Molin del Piano DI FIRENZE Careggi Stia S. Donnino Sieci Signa Pratovecchio Vinci Badia a Settimo FIRENZE Settignano Pontassieve Diacceto FI-PI-LI Castra Pelago Rosano RAVENNA Lastra a Signa Cerreto Guidi ✟ Villamagna Ponte a Cappiano Limite Scandicci Tosi Galluzzo Montemignaio Sovigliana Bagno a Ripoli S. Ellero C Capraia Ponte a Ema Fucecchio Mosciano Certosa Vallombrosa M Grassina S. Croce sull’Arno Rignano sull’Arno ✟ PIEVE Saltino Antella A PITIANA Poppi Y Ginestra Fiorentina S. Donato Empoli in Collina CM Tavarnuzze Chiesanuova Leccio MY Castelfranco di sotto Firenze e torrente Pesa S. Vincenzo a Torri CY Ponte a Elsa Impruneta Area Fiorentina Cerbaia A1 Reggello CMY FI-PI-LI S. Miniato ✟ S. Casciano in Val di Pesa FIRENZE-SIENA PIEVE DI CASCIA K S. Polo in Chianti Baccaiano Montopoli in Val d’Arno Il Ferrone Strada in Chianti Incisa Poppiano Montespertoli Mercatale in Val di Pesa Pian di Scò Cambiano Castelnuovo d’Elsa Cintoia Figline Passo dei Pecorai Palaia Dudda Greve in Chianti Loro Ciuffenna Gaville ✟ PIEVE DI Mura S. ROMOLO S. Giovanni Valdarno Tavarnelle in Val di Pesa AREZZO Terranuova Bracciolini Montaione ✟ Peccioli Certaldo S. -

Quaderni D'italianistica : Revue Officielle De La Société Canadienne

Elio Costa From locus amoris to Infernal Pentecost: the Sin of Brunetto Latini The fame of Brunetto Latini was until recently tied to his role in Inferno 15 rather than to the intrinsic literary or philosophical merit of his own works.' Leaving aside, for the moment, the complex question of Latini's influence on the author of the Commedia, the encounter, and particularly the words "che 'n la mente m' è fìtta, e or m'accora, / la cara e buona imagine paterna / di voi quando nel mondo ad ora ad ora / m'insegnavate come l'uom s'ettema" (82-85) do seem to acknowledge a profound debt by the pilgrim towards the old notary. Only one other figure in the Inferno is addressed with a similar expression of gratitude, and that is, of course, Virgil: Tu se' lo mio maestro e'I mio autore; tu se' solo colui da cu' io tolsi lo bello stilo che m'ha fatto onore. {Inf. 1.85-87) If Virgil is antonomastically the teacher, what facet of Dante's cre- ative personality was affected by Latini? The encounter between the notary and the pilgrim in Inferno 15 is made all the more intriguing by the use of the same phrase "lo mio maestro" (97) to refer to Virgil, silent throughout the episode except for his single utterance "Bene ascolta chi la nota" (99). That it is the poet and not the pilgrim who thus refers to Virgil at this point, when the two magisterial figures, one leading forward to Beatrice and the other backward to the city of strife, conflict and exile, provides a clear hint of tension between "present" and "past" teachers. -

De Vulgari Eloquentia

The De vulgari eloquentia, written by Dante in the early years of the fourteenth century, is the only known work of medieval literary theory to have been produced by a practising poet, and the first to assert the intrinsic superiority of living, vernacular languages over Latin. Its opening consideration of language as a sign-system includes foreshadowings of twentieth-century semiotics, and later sections contain the first serious effort at literary criticism based on close ana- lytical reading since the classical era. Steven Botterill here offers an accurate Latin text and a readable English translation of the treatise, together with notes and introductory material, thus making available a work which is relevant not only to Dante's poetry and the history of Italian literature, but to our whole understanding of late medieval poetics, linguistics and literary practice. Cambridge Medieval Classics General editor PETER DRONKE, FBA Professor of Medieval Latin Literature, University of Cambridge This series is designed to provide bilingual editions of medieval Latin and Greek works of prose, poetry, and drama dating from the period c. 350 - c. 1350. The original texts are offered on left-hand pages, with facing-page versions in lively modern English, newly translated for the series. There are introductions, and explanatory and textual notes. The Cambridge Medieval Classics series allows access, often for the first time, to out- standing writing of the Middle Ages, with an emphasis on texts that are representative of key literary traditions and which offer penetrating insights into the culture of med- ieval Europe. Medieval politics, society, humour, and religion are all represented in the range of editions produced here. -

The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians (Vol

1 Chapter I. Chapter II. Chapter III. Chapter I. Chapter II. Chapter III. Chapter IV. Chapter V. Chapter VI. Chapter I. Chapter II. Chapter I. Chapter II. Chapter III. Chapter IV. Chapter I. Chapter II. Chapter III. Chapter I. Chapter II. The Ancient History of the Egyptians, 2 Chapter III. Chapter IV. Chapter V. Chapter VI. Chapter I. Chapter II. Chapter I. Chapter II. Chapter III. Chapter IV. The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians (Vol. 1 of 6) by Charles Rollin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians (Vol. 1 of 6) Author: Charles Rollin Release Date: April 11, 2009 [Ebook #28558] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO 8859-1 The Ancient History of the Egyptians, 3 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE EGYPTIANS, CARTHAGINIANS, ASSYRIANS, BABYLONIANS, MEDES AND PERSIANS, MACEDONIANS AND GRECIANS (VOL. 1 OF 6)*** The Ancient History Of The Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians By Charles Rollin Late Principal of the University of Paris Professor of Eloquence in The Royal College And Member of the Royal Academy Of Inscriptions and Belles Letters Translated From The French In Six Volumes Vol. -

Dante's Political Life

Bibliotheca Dantesca: Journal of Dante Studies Volume 3 Article 1 2020 Dante's Political Life Guy P. Raffa University of Texas at Austin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Italian Language and Literature Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Raffa, Guy P. (2020) "Dante's Political Life," Bibliotheca Dantesca: Journal of Dante Studies: Vol. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant/vol3/iss1/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant/vol3/iss1/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Raffa: Dante's Political Life Bibliotheca Dantesca, 3 (2020): 1-25 DANTE’S POLITICAL LIFE GUY P. RAFFA, The University of Texas at Austin The approach of the seven-hundredth anniversary of Dante’s death is a propi- tious time to recall the events that drove him from his native Florence and marked his life in various Italian cities before he found his final refuge in Ra- venna, where he died and was buried in 1321. Drawing on early chronicles and biographies, modern historical research and biographical criticism, and the poet’s own writings, I construct this narrative of “Dante’s Political Life” for the milestone commemoration of his death. The poet’s politically-motivated exile, this biographical essay shows, was destined to become one of the world’s most fortunate misfortunes. Keywords: Dante, Exile, Florence, Biography The proliferation of biographical and historical scholarship on Dante in recent years, after a relative paucity of such work through much of the twentieth century, prompted a welcome cluster of re- flections on this critical genre in a recent volume of Dante Studies. -

Purgatório Político”: a Concepção De Poder Unitário De Dante Alighieri Na Florença Do Século Xiv

“PURGATÓRIO POLÍTICO”: A CONCEPÇÃO DE PODER UNITÁRIO DE DANTE ALIGHIERI NA FLORENÇA DO SÉCULO XIV “POLITICAL PURGATORY”: DANTE ALIGHIERI’S CONCEPTION OF UNITARY POWER IN THE 14TH CENTURY FLORENCE “PURGATORIO POLÍTICO”: EL CONCEPTO DE PODER UNITARIO DE DANTE ALIGUIERI EN LA FLORENCIA DEL SIGLO XIV Rodrigo Peixoto de Lima1 Mariana Bonat Trevisan2 Resumo Através desse estudo buscamos compreender as concepções políticas defendidas por Dante Alighieri, pensador laico florentino do século XIV, em suas obras. Particularmente, pretendemos analisar as voltadas à valorização do pensamento e do poder laicos (o poder temporal em comparação com o poder espiritual) presentes em sua obra Divina Comédia (em específico, no texto referente ao Purgatório), traçando comparativos com outro escrito do autor: De Monarchia. Palavras-chave: Dante Alighieri. Divina Comédia. Da Monarquia. Pensamento político na Baixa Idade Média. Abstract Through this study, we seek to understand the political conceptions defended by Dante Alighieri, a 14th century Florentine secular thinker, in his works. In particular, we intend to analyze the political conceptions aimed at valuing secular thought and power (the temporal power in comparison with the spiritual power) present in his work Divine Comedy (specifically, in the text referring to Purgatory), drawing comparisons with another writing by the author: De Monarchia. Keywords: Dante Alighieri. The Divine Comedy. The Monarchy. Political thought in the Late Middle Age. Resumen A través de este estudio tratamos de comprender las concepciones políticas defendidas por Dante Aliguieri, pensador laico florentino del siglo XIV, en sus obras. Particularmente, pretendemos analizar aquellas dirigidas a la valoración del pensamiento y poder laicos (el poder temporal en comparación con el poder espiritual) presente en su obra Divina Comedia (en específico, en el texto referido al Purgatorio), estableciendo comparaciones con otro escrito del autor: De la Monarquía. -

Emotional Minds and Bodies in the Suicide Narratives of Dante's Inferno

Emotional Minds and Bodies in the Suicide Narratives of Dante’s Inferno Emma Louise Barlow University of Technology Sydney Abstract: Suicide plays a dynamic role in both the narrative and structure of Dante’s Inferno, and yet, in accordance with there being no term for the act in European languages until the 1600s, the poet mentions it only euphemistically: Dido ‘slew herself for love’ (Inf. 5.61), Pier della Vigna describes suicide as a process in which ‘the ferocious soul deserts the body / after it has wrenched up its own roots’ (Inf. 13.94–95), and the anonymous Florentine suicide simply ‘made [his] house into [his] gallows’ (Inf. 13.151). It is thus unsurprising that the notion of mental health in connection with suicide is eQually absent in explicit terms. Reading between the lines of Dante’s poetry, however, it becomes clear that the emotive language and embodied hybridity associated with the suicides within Dante’s oltremondo, and of Dante the pilgrim as he responds to their narratives, highlights a heterogeneous yet shared experience of loss and despair, mirroring contemporary understandings of mental health issues. Through an analysis of the emotive language associated with the narratives of a number of Dante’s suicides, and the hybrid embodiment of numerous suicides inscribed in Dante’s text, this paper hopes to explore the ways in which, even inadvertently, Dante reflects on the distancing of the suicides from the civic bodies of their communities, from their own physical bodies, and from the vital rationality of their human minds, and thus to investigate the ways in which the lack of emotional wellbeing experienced by the suicides forces them to the edges of society’s, and their own, consciousness. -

Thomas Ricklin, « Filosofia Non È Altro Che Amistanza a Sapienza » Nadja

Thomas Ricklin, « Filosofia non è altro che amistanza a sapienza » Abstract: This is the opening speech of the SIEPM world Congress held in Freising in August 2012. It illustrates the general theme of the Congress – The Pleasure of Knowledge – by referring mainly to the Roman (Cicero, Seneca) and the medieval Latin and vernacular tradition (William of Conches, Robert Grosseteste, Albert the Great, Brunetto Latini), with a special emphasis on Dante’s Convivio. Nadja Germann, Logic as the Path to Happiness: Al-Fa-ra-bı- and the Divisions of the Sciences Abstract: Divisions of the sciences have been popular objects of study ever since antiquity. One reason for this esteem might be their potential to reveal in a succinct manner how scholars, schools or entire societies thought about the body of knowledge available at their time and its specific structure. However, what do classifications tell us about thepleasures of knowledge? Occasionally, quite a lot, par- ticularly in a setting where the acquisition of knowledge is considered to be the only path leading to the pleasures of ultimate happiness. This is the case for al-Fa-ra-b-ı (d. 950), who is at the center of this paper. He is particularly interesting for a study such as this because he actually does believe that humanity’s final goal consists in the attainment of happiness through the acquisition of knowledge; and he wrote several treatises, not only on the classification of the sciences as such, but also on the underlying epistemological reasons for this division. Thus he offers excellent insight into a 10th-century theory of what knowledge essentially is and how it may be acquired, a theory which underlies any further discussion on the topic throughout the classical period of Islamic thought. -

Appendix A: Selective Chronology of Historical Events

APPENDIX A: SELECTIVE CHRONOLOGY OF HIsTORICaL EVENTs 1190 Piero della Vigna born in Capua. 1212 Manente (“Farinata”) degli Uberti born in Florence. 1215 The Buondelmonte (Guelf) and Amidei (Ghibelline) feud begins in Florence. It lasts thirty-three years and stirs parti- san political conflict in Florence for decades thereafter. 1220 Brunetto Latini born in Florence. Piero della Vigna named notary and scribe in the court of Frederick II. 1222 Pisa and Florence wage their first war. 1223 Guido da Montefeltro born in San Leo. 1225 Piero appointed Judex Magnae Curia, judge of the great court of Frederick. 1227 Emperor Frederick II appoints Ezzelino da Romano as commander of forces against the Guelfs in the March of Verona. 1228 Pisa defeats the forces of Florence and Lucca at Barga. 1231 Piero completes the Liber Augustalis, a new legal code for the Kingdom of Sicily. 1233 The cities of the Veronese March, a frontier district of The Holy Roman Empire, transact the peace of Paquara, which lasts only a few days. © The Author(s) 2020 249 R. A. Belliotti, Dante’s Inferno, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40771-1 250 AppeNDiX A: Selective ChrONOlOgY Of HistOrical EveNts 1234 Pisa renews war against Genoa. 1235 Frederick announces his design for a Holy Roman Empire at a general assembly at Piacenza. 1236 Frederick assumes command against the Lombard League (originally including Padua, Vicenza, Venice, Crema, Cremona, Mantua, Piacenza, Bergamo, Brescia, Milan, Genoa, Bologna, Modena, Reggio Emilia, Treviso, Vercelli, Lodi, Parma, Ferrara, and a few others). Ezzelino da Romano controls Verona, Vicenza, and Padua.