MJT 8-2 Full OK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song of the Beauforts

Song of the Beauforts Song of the Beauforts No 100 SQUADRON RAAF AND BEAUFORT BOMBER OPERATIONS SECOND EDITION Colin M. King Air Power Development Centre © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Approval has been received from the owners where appropriate for their material to be reproduced in this work. Copyright for all photographs and illustrations is held by the individuals or organisations as identified in the List of Illustrations. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release, distribution unlimited. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. First published 2004 Second edition 2008 Published by the Air Power Development Centre National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: King, Colin M. Title: Song of the Beauforts : No 100 Squadron RAAF and the Beaufort bomber operations / author, Colin M. King. Edition: 2nd ed. Publisher: Tuggeranong, A.C.T. : Air Power Development Centre, 2007. ISBN: 9781920800246 (pbk.) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Beaufort (Bomber)--History. Bombers--Australia--History World War, 1939-1945--Aerial operations, Australian--History. -

Type X Pottery) Morobe Province) Papua New Guinea: Petrography and Possible Micronesian Relationships

Type X Pottery) Morobe Province) Papua New Guinea: Petrography and Possible Micronesian Relationships JIM SPECHT, IAN LILLEY, AND WILLIAM R. DICKINSON THE STUDY OF PREHISTORIC INTERACTION BETWEEN ISLANDS AND ARCHIPEL agoes of the Pacific has been largely concerned with processes of colonization and the development of exchange networks, both of which involved a complex flow of people, goods, knowledge, languages and genes. As Gosden and Pavlides (1994: 163) point out, however, this does not mean that "Pacific societies ... were in contact over vast distances all the time," and there must have been occa sions when interaction was not planned, predictable, or sustained, nor did it in volve the large-scale relocation of people. Such contacts no doubt contributed to the complex archaeological and ethnographic picture in many areas, but some might have left little or no expression in the archaeological record (cf. Rainbird 2004: 246; Spriggs 1997: 190). We discuss here a possible example of this on Huon Peninsula on the north coast of New Guinea, where aspects of a prehistoric pottery known as Type X suggest contact between the peninsula and the Palau Islands of western Micronesia about 1000 years ago. Throughout the article, we use the term "Micronesia" solely in a geographical sense, without cultural impli cations (cf. Rainbird 2004). Prehistoric links involving both colonization and the transfer of technologies between the island groups of Melanesia-West Polynesia and various parts of cen tral and eastern Micronesia seem well established through the evidence of linguis tics (e.g., Bayard 1976; Blust 1986; Pawley 1967; Shutler and Marck 1975: 101), archaeology (e.g., Athens 1990a:29, 1990b:173, 1995:268; Ayres 1990:191, 203; Intoh 1996,1997,1999), biological anthropology (e.g., Swindler and Weis ler 2000; Weisler and Swindler 2002), and cultural practices such as kava drinking (Crowley 1994). -

Terra Australis 26

terra australis 26 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land. -

Iota Directory of Islands Regional List British Isles

IOTA DIRECTORY OF ISLANDS sheet 1 IOTA DIRECTORY – QSL COLLECTION Last Update: 22 February 2009 DISCLAIMER: The IOTA list is copyrighted to the Radio Society of Great Britain. To allow us to maintain an up-to-date QSL reference file and to fill gaps in that file the Society's IOTA Committee, a Sponsor Member of QSL COLLECTION, has kindly allowed us to show the list of qualifying islands for each IOTA group on our web-site. To discourage unauthorized use an essential part of the listing, namely the geographical coordinates, has been omitted and some minor but significant alterations have also been made to the list. No part of this list may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise. A shortened version of the IOTA list is available on the IOTA web-site at http://www.rsgbiota.org - there are no restrictions on its use. Islands documented with QSLs in our IOTA Collection are highlighted in bold letters. Cards from all other Islands are wanted. Sometimes call letters indicate which operators/operations are filed. All other QSLs of these operations are needed. EUROPE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN # ENGLAND / SCOTLAND / WALES B EU-005 G, GM, a. GREAT BRITAIN (includeing England, Brownsea, Canvey, Carna, Foulness, Hayling, Mersea, Mullion, Sheppey, Walney; in GW, M, Scotland, Burnt Isls, Davaar, Ewe, Luing, Martin, Neave, Ristol, Seil; and in Wales, Anglesey; in each case include other islands not MM, MW qualifying for groups listed below): Cramond, Easdale, Litte Ross, ENGLAND B EU-120 G, M a. -

Teacher Education in Papua New Guinea: Policy and Practice 1946-1996

TEACHER EDUCATION IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: POLICY AND PRACTICE 1946-1996 VOLUME I Pamela Anne Quartermaine, T.C.(W.Aust.), A.I.Ed.(London), M.A.(M.S.U.) SQ...c cu-· o\ ci ~ <:J<-0 < ?c ~ ~ · Cc.v.,.. .p 0 \sot ~ £cl0 c._ Q...b 00 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania at Launceston June 2001 DECLARATION I certify that this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma in any university or other institution and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis . o---LI Pamela Anne Quartermaine 2.$"'. b· ..200/ AUTHORITY OF ACCESS This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Pamela Anne Quartermaine 2.S-. b. z_ool ABSTRACT This was a study in Papua New Guinea (PNG) of the planning and implementation of a new three-year teacher education programme, the Diploma in Teaching (Primary). What the indigenous staff in the nine residential colleges did to introduce the programme between 1991 and 1993, was seen at the outset by the writer to be an important culmination of all that preceded the innovation. The context, therefore, is detailed historically for the 50 years from 1946 to 1996, indicating teacher training and teacher education policy development, the process of staff localisation (indigenisation) and college programme evolution. The pioneering work of indigenous PNG school teachers was a significant contribution to the country's development, consequently the way they were prepared for their work and roles was a useful investigation. -

Trobib 2011.Pdf

1 A Trobriand/Massim Bibliography Seventh Edition: July 2011 Allan C. Darrah Jay B. Crain The DEPTH Project: Department of Anthropology CSUS In 1965 Crain created the first Trobriand Bibliography which was updated in 1993 by Gardener and Darrah and expanded to include materials from other islands in the Massim. The 1995 edition was compiled by Darrah with the help of Claire Chiu and the members of the Trobriand Seminar at CSUS. In 1999 and again in 2000 Darrah was responsible for the updates. Darrah and Crain have completed this 2011 update. This bibliography is very much a work in progress, containing a few incomplete citations and no doubt many errors. Anyone who would like to make additions or corrections should contact Darrah [email protected] or Crain [email protected]. Criteria for inclusion of materials has been flexible in terms of both geography and subject matter. The geographic focus has always been the Trobriand Islands and neighboring societies associated with the kula; however, there are also items which focus on Milne Bay Province and Papua New Guinea. Even though there have been no limitations for inclusion based on subject matter the main thrust has been ethnography. One major exception to the geographic criteria has been made; works by and about major Massim scholars, which contain little or no information about the Massim, are included. The compilers wish to acknowledge major contributions made by Macintyre (1983) and more recently Hide (2000) and most especially the superb PNG bibliography of Terrance Hays (http://www.papuaweb.org/bib/hays/ng/index.html.) Important contributions were also made by Leach, J. -

Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea

AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Working Paper No. 3 WEST SEPIK PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, R.L. Hide, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes, T. Nen, E. Nirsie, J. Risimeri and M. Woruba Department of Human Geography, The Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia. REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 Correct Citation: Bourke, R.M., Allen, B.J., Hide, R.L., Fritsch, D., Grau, R., Lowes, E., Nen, T., Nirsie, E., Risimeri, J. and Woruba, M. (2002). West Sepik Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No. 3. Land Management Group, Department of Human Geography, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra. Revised edition. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry: West Sepik Province: text summaries, maps, code lists and village identification. Rev. ed. ISBN 0 9579381 3 6 1. Agricultural systems – Papua New Guinea – West Sepik Province. 2. Agricultural geography – Papua New Guinea – West Sepik Province. 3. Agricultural mapping – Papua New Guinea – West Sepik Province. I. Bourke, R.M. (Richard Michael). II. Australian National University. Land Management Group. (Series: Agricultural systems of Papua New Guinea working paper; no. 3). 630.99577 Cover Photograph: The late Gore Gabriel clearing undergrowth from a pandanus nut grove in the Sinasina area, Simbu Province (R.L. Hide). ii PREFACE Acknowledgments The following organizations have contributed financial support to this project: The Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University; The Australian Agency for International Development; the Papua New Guinea-Australia Colloquium through the International Development Program of Australian Universities and Colleges and the Papua New Guinea National Research Institute; the Papua New Guinea Department of Agriculture and Livestock; the University of Papua New Guinea; and the National Geographic Society, Washington DC. -

Coastal Mobility and Lithic Supply Lines in Northeast New Guinea

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0713-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Coastal mobility and lithic supply lines in northeast New Guinea Dylan Gaffney1,2 & Glenn R. Summerhayes3,4 Received: 1 August 2018 /Accepted: 17 September 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract This paper investigates how coastal mobility and a community’s place within regional trade networks intersect with technological organisation. To do this, we identified different types of lithic production and exchange during the late pre-colonial period at three coastal sites around Madang in northeast New Guinea. The study is the first major technological and sourcing study in this area. Consistent with terrestrial models, lithic technological analysis crucially shows that groups with higher levels of coastal mobility (1) were reducing a wider range of lithic materials and (2) reduced material less intensively than groups with indirect access. Conversely, groups with lower coastal mobility levels (1) were flaking a restricted range of lithic materials and (2) reduced material more intensively. Geochemical analysis, using X-ray fluorescence, shows that at all three sites obsidian artefacts exclusively derived from Kutau/Bao (Talasea) in West New Britain. This indicates that, by about 600 years ago through to the late nineteenth century, the Kutau/Bao source had become a specialised export product, being fed into major distribution conduits operational along the northeast coast. Importantly, there is no evidence for exchange with other sources such as Admiralties or Fergusson Island obsidian. This is contrastive to the Sepik coast, where obsidian from the Admiralties Islands featured promi- nently alongside West New Britain obsidian, and suggests the emergence of different coastal supply lines feeding the northeast Madang coast and the north Sepik coast. -

Primary Schools

Batch Payment by Bank and School for Selected Sector Grouping Payment: 1 Batch No: 1 Status: Batch Payment Finalized Sector: PRI Bank: BSP Province: ALL Total Previously Sent To Be Sent School Name Code Province Sector Enrolments Amounts Enrolment Amount Total Total Bank BSB Branch Name Account No Account Name Enrolment Amount PRI Sector Schools Nangananga Primary School 65425 ENBP PRI 496 58,384.16 496 0 496 58,384.16 BSP 088964 Kokopo 68719732 NANGANANGA COMMUNITY Tapo Primary School 65450 ENBP PRI 440 51,792.40 440 0 440 51,792.40 BSP 088964 Kokopo 1001388496 TAPO PRIMARY Vatara Primary School 65372 ENBP PRI 146 17,185.66 146 0 146 17,185.66 BSP 088964 Kokopo 1000639050 VATARA COMMUNITY St Theresa Primary School (Drekikier) 61417 ESP PRI 173 20,363.83 173 0 173 20,363.83 BSP 088333 Maprik 1000777354 DREKIKIR CATHOLIC PRIMARY Mendo Primary School 56023 SHP PRI 498 58,619.58 498 0 498 58,619.58 BSP 088315 Mendi 1000911351 Mendo Community School Kongola Primary School 67044 AROB PRI 139 16,361.69 139 0 139 16,361.69 BSP 088336 Buka 1004093868 KONGOLA PRIMARY SCHOOL Sangera Primary School 61219 ESP PRI 250 23,542.00 0 0 250 23,542.00 BSP 088306 Wewak 1000782063 SANGERA PRIMARY Naveo Primary School 65427 ENBP PRI 133 15,655.43 133 0 133 15,655.43 BSP 088965 Rabaul 1000182112 NAVEO PRIMARY Sikut Primary School 65383 ENBP PRI 98 11,535.58 98 0 98 11,535.58 BSP 088964 Kokopo 1000641717 SIKUT COMMUNITY Tavilo Primary School 65023 ENBP PRI 188 22,129.48 188 0 188 22,129.48 BSP 088964 Kokopo 1000638932 TAVILO PRIMARY St Mary'S Kangri Primary School -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

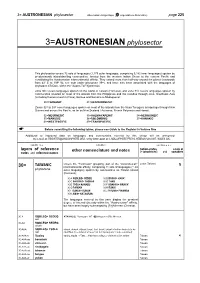

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 225 3=AUSTRONESIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector covers 72 sets of languages (1,179 outer languages, comprising 3,182 inner languages) spoken by predominantly island-dwelling communities, located from the western Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific and constituting the Austronesian intercontinental affinity. They extend more than half-way around the planet (eastwards from 43º E to 109º W; see note under phylozone 39=), and have also been associated with the languages of phylozone 47=Daic, within the "Austro-Tai" hypothesis. Zone 30= covers languages spoken on the island of Taiwan (Formosa), and zone 31= covers languages spoken by communities situated on most of the islands from the Philippines and the Celebes through Java, Southeast Asia (including Hainan island in China), Borneo and Sumatra to Madagascar: 30=TAIWANIC 31=HESPERONESIC Zones 32= to 39= cover languages spoken on most of the islands from the Nusa Tenggera archipelago through New Guinea and across the Pacific, as far as New Zealand / Aotearoa, French Polynesia and Hawaii: 32=MESONESIC 33=HALMAYAPENIC 34=NEOGUINEIC 35=MANUSIC 36=SOLOMONIC 37=KANAKIC 38=WESTPACIFIC 39=TRANSPACIFIC Before consulting the following tables, please see Guide to the Register in Volume One Les données supplémentaires -

3=AUSTRONESIAN Phylosector

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 225 3=AUSTRONESIAN phylosector This phylosector covers 72 sets of languages (1,179 outer languages, comprising 3,182 inner languages) spoken by predominantly island-dwelling communities, located from the western Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific and constituting the Austronesian intercontinental affinity. They extend more than half-way around the planet (eastwards from 43º E to 109º W; see note under phylozone 39=), and have also been associated with the languages of phylozone 47=Daic, within the "Austro-Tai" hypothesis. Zone 30= covers languages spoken on the island of Taiwan (Formosa), and zone 31= covers languages spoken by communities situated on most of the islands from the Philippines and the Celebes through Java, Southeast Asia (including Hainan island in China), Borneo and Sumatra to Madagascar: 30=TAIWANIC 31=HESPERONESIC Zones 32= to 39= cover languages spoken on most of the islands from the Nusa Tenggera archipelago through New Guinea and across the Pacific, as far as New Zealand / Aotearoa, French Polynesia and Hawaii: 32=MESONESIC 33=HALMAYAPENIC 34=NEOGUINEIC 35=MANUSIC 36=SOLOMONIC 37=KANAKIC 38=WESTPACIFIC 39=TRANSPACIFIC ☛ Before consulting the following tables, please see Guide to the Register in Volume One Additional or improved data on languages and communities covered by this sector will be welcomed by e-mail at: [email protected], or by letter-post at: LINGUASPHERE PRESS, HEBRON SA34 0XT, WALES (UK). COLUMN 1 & 2 COLUMN 3 -

Confronting Fiji Futures

Index A’ana, 6, 7, 29, 57, 59 America, 56; early contacts Ponape, 73; Administration: changes to New Guinea influence on Nanpei, 78; Republican protectorate, 20; of Marshall Islands, ideas Ponape, 75, 90; war with Spain, 19; of New Guinea, 19; Ponape, role 779; Lauaki’s call to, 58, 61; partition in crushing revolt, 10613; see also of Samoa, 31; resistance to German Colonial administration; District ad sovereignty Samoa, 18, 28; settler ministration claims to land Samoa, 26 Admiralty, B & G, 169 American Board of Commissioners for Admiralty Islands, 22, 125, 140, 194, Foreign Missions, see Boston Missionary 20910; description of, 1523; pacifica Society tion of, 1528 American Samoa, see Samoa, American Advisory council: New Guinea, to American traders, see Traders Governor, 161; Ponape, Nanpei’s, Ancestors, New Guinea, Germans mis 901, 92, 98, 115, 116, 203, 209, 220; taken for, 164 see also Puin en lolokon\ Samoa, to Anchorite Islands, 125 Governor, 53 A ngala, see ‘Big m an’ Africa, 21, 22, 34, 71, 99 Angaur, 112, 118 African colonies, 21 Angoram, 195 Agreement, Spain and Germany 1885, 79 Annexation: Caroline Islands, 74; New Agriculture: New Guinea, expanding, Guinea, 1256, 164 140; Ponape, potential, 80; Samoa, 51, Ant Islands, 78, 89, 90, 91, 93, 115 (extent 1914) 70, (limitations) 39; see Anut, 163, 168 also Plantations Apalberg, 109 Ahi people, 191 Apia, 18, 26, 27, 30, 49, 53, 56, 57, 59, A’iga, 7, 60, 62 61, 71; base for Godeffroys, 16; de Aimeliik, 118 scription of, 4, 27; see also Municipality Aitape, 22, 161, 170, 183, 192, 194, Apolima, 3, 6 195 Arcona, SMS, 63 Aleniang, 75, 76 Arms trade: New Guinea (New Ireland) Alexishafen, 186 138, (part of copra trade) 120, 123; Ali’i, 6 , 11 Ponape, 77, 83; Samoa, 35, (growth Ali’i Sili, 34, 38, 55, 57, 67, 69, 71, 214, in) 268 218; question of succession, 556; Asiata Taetoloa, 62, 63 solution to succession, 679; see also Astrolabe Bay, 163, 164, 167, 173, 177 Paramount chieftaincy.