Song of the Beauforts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Military and Veterans' Health

Volume 16 Number 1 October 2007 Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health Deployment Health Surveillance Australian Defence Force Personnel Rehabilitation Blast Lung Injury and Lung Assist Devices Shell Shock The Journal of the Australian Military Medicine Association Every emergency is unique System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. We focus on providing innovative products developed with the user in mind. The result is a range of products that are tough, perfectly coordinated with each other and adaptable for every rescue operation. Weinmann (Australia) Pty. Ltd. – Melbourne T: +61-(0)3-95 43 91 97 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Weinmann (New Zealand) Ltd. – New Plymouth T: +64-(0)6-7 59 22 10 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Emergency_A4_4c_EN.indd 1 06.08.2007 9:29:06 Uhr Table of contents Editorial Inside this edition . 3 President’s message . 4 Editor’s message . 5 Commentary Initiating an Australian Deployment Health Surveillance Program . 6 Myers – The dawn of a new era . 8 Original Articles The Australian Defence Deployment Health Surveillance Program – InterFET Pilot Project . 9 Review Articles Rehabilitation of injured or ill ADF Members . 14 What is the effectiveness of lung assist devices in blast injury: A literature review . .17 Short Communications Unusual Poisons: Socrates’ Curse . 25 Reprinted Articles A contribution to the study of shell shock . 27 Every emergency is unique Operation Sumatra Assist Two . 32 System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Biography Surgeon Rear Admiral Lionel Lockwood . 35 Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. -

RUSI of NSW Article

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article USI Vol61 No2 Jun10:USI Vol55 No4/2005 21/05/10 1:31 PM Page 24 CONTRIBUTED ESSAY Conflict in command during the Kokoda campaign of 1942: did General Blamey deserve the blame? Rowan Tracey General Sir Thomas Blamey was commander-in-chief of the Australian Military Forces during World War II. Tough and decisive, he did not resile from sacking ineffective senior commanders when the situation demanded. He has been widely criticised by more recent historians for his role in the sackings of Lieutenant-General S. F. Rowell, Major-General A. S. Allen and Brigadier A. W. Potts during the Kokoda Campaign of 1942. Rowan Tracey examines each sacking and concludes that Blameyʼs actions in each case were justified. On 16 September 1950, a small crowd assembled in High Command in Australia in 1942 the sunroom of the west wing of the Repatriation In September 1938, Blamey was appointed General Hospital at Heidelberg in Melbourne. The chairman of the Commonwealth’s Manpower group consisted of official military representatives, Committee and controller-general of recruiting on the wartime associates and personal guests of the central recommendation of Frederick Shedden, secretary of figure, who was wheelchair bound – Thomas Albert the Department of Defence, and with the assent of Blamey. -

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

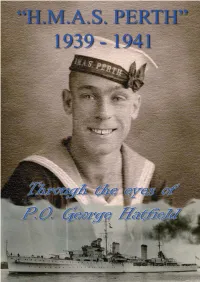

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Fighter Squadron

REGISTERED FOR POSTING AS A PERIODICAL CATEGORY B JOURNAL AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA PRICE $1.55 A new $500,000 overseas departure and transit lounge at Perth Inter national Airport was officially opened on 6 February, greatly improving facilities at the airport for International passengers. The lounge can handle MONTH LY 500 passengers per hour and will allow for better security measures to be taken at the airport. The next two Boeing 727—200 for Ansett and TAA will be registered NOTES VH-RMK and VH—TBM respectively. TAA have already retired,on 14 February 1976^Boeing 727 VH-TJA "James Cook" (c/n 18741) which has flown 37,643 hours. To mark the anniversary of Ansett Airways first commercial flight, Ansett Airlines of Australia carried out a special Melbourne-Hamilton return flight on Tuesday, 17 February, 1976. The initial flight was made on CIVIL 17 February 1936 in a Fokker Universal VH-UTO (c/n 422) piloted by Captain Vern Cerche, During Ansett's anniversary year, a replica of VH—UTO is being displayed at Melbourne Airport, Tullamarine. Fokker Friendship The Federal Government will increase air navigation charges by 15 per VH—FNU (c/n 10334) piloted by Captain John Raby was used for the cent, the increase to apply from 1 December 1975. The Transport Minister, re-enactment flight, and passengers Included Captain Cec Long, one of Mr. Nixon, said the rise was unavoidable because of losses in operating and Ansett's first pilots, and three of the passengers on the 1936 flight. A maintaining air facilities. -

AHSA 1999 AH Vol 30 No 02.Pdf

m I 1 '1: tfM / 1. I iWPi I 1 I i 1 I i I liililfifi •1 E iiiS » fe ■'ll 1 1 #■'m II ill II The Journal of the Aviation Historical Society of Australia Inc . A0033653P Volume 30 Number 2 March 1999 PslS liim^ II iwiiiiiiH Wiij^ ■ smi WtK^M -'•V| mmm ii»i . if II I ii K i If I I : I I iiiiiiii 1:1: ■ ■W I I ■i:, Warners Wooden Wonders i 1 I Milton A. yoe) Taylor i gsg^rnmmtmv^^ Paddy Heffernan ~ Series ~ Part 8 A.H.S.A. 40™ ANNIVERSARY 1959M 999 .fill i 1' ■ The Journal of the AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY of ACSTRALIA Inc. A00336533P Volume 30 - Number 2 - March 1999 EDITORIAL EDITORS, DESIGN & PRODUCTION I have believed for some considerable time that we must capture our Aviation history NOW before it all goes. It is true Bill and Judith Baker to say that every day we loose bits of it. So seize the day and Address all correspondence to; do something about it. You must be interested in this subject The Editor, AHSA, or you would not be a member or be reading this. P.O. Box 2007, South Melbourne 3205 Victoria, Australia. We have a wide variety of topics in this issue and includes 03 9583 4072 Phone & Fax two new types - ‘Seen at’, which comes from a personal Subscription Rates; photographic album, and ‘Final Report’ which comes Australia A$40, originally from a RAAF report and is quite interesting. These Rest of World A$50. Surface Mail two could be duplicated anyone with a few photos or access A$65. -

September 2006 Vol

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 ListeningListeningTHE AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2006 VOL. 29 No.4 PostPost The official journal of THE RETURNED & SERVICES LEAGUE OF AUSTRALIA POSTAGE PAID SURFACE WA Branch Incorporated • PO Box Y3023 Perth 6832 • Established 1920 AUSTRALIA MAIL Viet-NamViet-Nam –– 4040 YearsYears OnOn Battle of Long-Tan Page 9 90th Anniversary – Annual Report Page 11 The “official” commencement date for the increased Australian commitment, this commitment “A Tribute to Australian involvement in Viet-Nam is set at 23 grew to involve the Army, Navy and Air Force as well May 1962, the date on which the (then) as civilian support, such as medical / surgical aid Minister for External Affairs announced the teams, war correspondents and officially sponsored Australia’s decision to send military instructors to entertainers. Vietnam. The first Australian troops At its peak in 1968, the Australian commitment Involvement in committed to Viet-Nam arrived in Saigon on amounted to some 83,000 service men and women. 3rd August 1962. This group of advisers were A Government study in 1977 identified some 59,036 Troops complete mission Viet-Nam collectively known as the “Australian Army males and 484 females as having met its definition of and depart Camp Smitty Training Team” (AATTV). “Viet-Nam Veterans”. Page 15 1962 – 1972 As the conflict escalated, so did pressure for Continue Page 5. 2 THE LISTENING POST August/September 2006 FULLY LOADED DEALS DRIVE AWAY NO MORE TO PAY $41,623* Metallic paint (as depicted) $240 extra. (Price applies to ‘05 build models) * NISSAN X-TRAIL ST-S $ , PATHFINDER ST Manual 40th Anniversary Special Edition 27 336 2.5 TURBO DIESEL PETROL AUTOMATIC 7 SEAT • Powerful 2.5L DOHC engine • Dual SRS airbags • ABS brakes • 128kW of power/403nm Torque • 3,000kg towing capacity PLUS Free alloy wheels • Free sunroof • Free fog lamps (trailer with brakes)• Alloy wheels • 5 speed automatic FREE ALLOY WHEEL, POWER WINDOWS * $ DRIVE AWAY AND LUXURY SEAT TRIM. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

Australia's Naval Shipbuilding Enterprise

AUSTRALIA’S NAVAL SHIPBUILDING ENTERPRISE Preparing for the 21st Century JOHN BIRKLER JOHN F. SCHANK MARK V. ARENA EDWARD G. KEATING JOEL B. PREDD JAMES BLACK IRINA DANESCU DAN JENKINS JAMES G. KALLIMANI GORDON T. LEE ROGER LOUGH ROBERT MURPHY DAVID NICHOLLS GIACOMO PERSI PAOLI DEBORAH PEETZ BRIAN PERKINSON JERRY M. SOLLINGER SHANE TIERNEY OBAID YOUNOSSI C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1093 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9029-4 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Australian government will produce a new Defence White Paper in 2015 that will outline Australia’s strategic defense objectives and how those objectives will be achieved. -

Moshe Goldberg Eulogy 2

EULOGY FOR MOSHE (MORRY) GOLDBERG GIVEN AT HIS FUNERAL ON SUNDAY 20 JANUARY 2013 Morry Asher GOLDBERG was born at Jerusalem, Palestine on 12 APRIL,1926 and originally enlisted and served in the Militia as N479345 prior to enlisting and serving as NX178973 PRIVATE Morry GOLDBERG in the 2nd/48th Australian Infantry Battalion AIF at Cowra NSW on 1st July 1944, then just 18 years of age. During his service with the Battalion, Morry was promoted to Corporal, taking part in its heavy fighting against the Japanese on Tarakan as part of Operation ‘Oboe’ in the South West Pacific Theatre. Morry was discharged on 10th March, 1947. The 2/48th Battalion AIF was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army raised in August 1940 at the Wayville Showgrounds in Adelaide, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Victor Windeyer, (later Major General Sir Victor Windeyer, KBE, CB, DSO and Bar, PC KC) a former Militia officer 9and later a Judge of the high Court of Australia) who had previously commanded the Sydney University Regiment. Together with the 2/23rd and 2/24th Battalions the 2/48th Battalion formed part of the 26th Brigade and was initially assigned to the 7th Division, although it was later transferred to the 9th Division in 1941 when it was deployed to the Middle East. While there, it saw action during the siege of Tobruk where it suffered the loss of 38 men killed in action and another 18 who died of their wounds and the Second Battle of El Alamein before being returned to Australia in order to take part in the fighting in New Guinea following Japan’s entry into the war. -

The Combat Effectiveness of Australian and American Infantry Battalions in Papua in 1942-1943 Bryce Michael Fraser University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 The combat effectiveness of Australian and American infantry battalions in Papua in 1942-1943 Bryce Michael Fraser University of Wollongong Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Faculty of Arts School of History and Politics The combat effectiveness of Australian and American infantry battalions in Papua in 1942-1943 Bryce Michael Fraser, BA. This thesis is presented as the requirement for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong March 2013 CERTIFICATION I, Bryce Michael Fraser, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. B M Fraser 25 March 2013 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES iv ABBREVIATIONS vii ABSTRACT viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Theory and methodology 13 Chapter 2: The campaign and the armies in Papua 53 Chapter 3: Review of literature and sources 75 Chapter 4 : The combat readiness of the battalions in the 14th Brigade 99 Chapter 5: Reinterpreting the site and the narrative of the battle of Ioribaiwa 135 Chapter 6: Ioribaiwa battle analysis 185 Chapter 7: Introduction to the Sanananda road 211 Chapter 8: American and Australian infantry battalions in attacks at the South West Sector on the Sanananda road 249 Chapter 9: Australian Militia and AIF battalions in the attacks at the South West Sector on the Sanananda road. -

9 Australian Infantry Division (1941-42)

14 January 2019 [9 AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1940 – 42)] th 9 Australian Infantry Division (1) Advanced Headquarters, 9th Australian Division, Signals & Employment Platoon Rear Headquarters, 9th Australian Division & Signals th 20 Australian Infantry Brigade (2) Headquarters, 20th Australian Infantry Brigade, ‘J’ Section Signals & 58th Light Aid Detachment 2nd/13th Australian Infantry Battalion 2nd/15th Australian Infantry Battalion 2nd/17th Australian Infantry Battalion 20th Australian Infantry Brigade Anti-Tank Company 24th Australian Infantry Brigade Headquarters, 24th Australian Infantry Brigade, ‘J’ Section Signals & 76th Light Aid Detachment 2nd/28th Australian Infantry Battalion nd nd 2 /32 Australian Infantry Battalion (3) 2nd/43rd Australian Infantry Battalion 24th Australian Infantry Brigade Anti-Tank Company 26th Australian Infantry Brigade Headquarters, 26th Australian Infantry Brigade, ‘J’ Section Signals & 78th Light Aid Detachment 2nd/23rd Australian Infantry Battalion 2nd/24th Australian Infantry Battalion 2nd/48th Australian Infantry Battalion 26th Australian Infantry Brigade Anti-Tank Company Divisional Troops th 9 Australian Divisional Cavalry Regiment (3) 82nd Light Aid Detachment nd nd 2 /2 Australian Machine Gun Battalion (3) © w w w . BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 14 January 2019 [9 AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1940 – 42)] th Headquarters, Royal Australian Artillery, 9 Australian Division 2nd/7th Australian Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery 2nd/8th Australian Field Regiment, Royal Australian -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly. the Australian Fleet Air

We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………………………………………………….. Abstract This thesis examines a small component of the Australian Navy, the Fleet Air Arm. Naval aviators have been contributing to Australian military history since 1914 but they remain relatively unheard of in the wider community and in some instances, in Australian military circles. Aviation within the maritime environment was, and remains, a versatile weapon in any modern navy but the struggle to initiate an aviation branch within the Royal Australian Navy was a protracted one. Finally coming into existence in 1947, the Australian Fleet Air Arm operated from the largest of all naval vessels in the post battle ship era; aircraft carriers. HMAS Albatross, Sydney, Vengeance and Melbourne carried, operated and fully maintained various fixed-wing aircraft and the naval personnel needed for operational deployments until 1982. These deployments included contributions to national and multinational combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. With the Australian government’s decision not to replace the last of the aging aircraft carriers, HMAS Melbourne, in 1982, the survival of the Australian Fleet Air Arm, and its highly trained personnel, was in grave doubt. This was a major turning point for Australian Naval Aviation; these versatile flyers and the maintenance and technical crews who supported them retrained on rotary aircraft, or helicopters, and adapted to flight operations utilising small compact ships.