A Demonstration of Organized Hypocrisy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Waves

Making Waves Sea Blindness and Australia’s Second Sea Navy (RAN), HMAS Stirling, at Garden Island, off Fre- Brian K. Wentzell mantle, Western Australia. The base is now the home of all Collins-class submarines, five Anzac frigates and a It is interesting to examine countries with coasts on more single fleet tanker. There is also a heliport to support he- than one ocean. Which coast is emphasized illustrates licopters assigned to the ships. Other resources, includ- much about the country’s history. Thus in Canada, the ing the landing ships, air warfare destroyers, coastal pa- focus has historically been on the Atlantic Ocean. Only trol vessels and mine warfare forces would have to deploy recently has focus changed to the Pacific coast and even from the east coast and northern areas to counter a major more recently the Arctic coast. For Australia the focus has maritime threat in the eastern Indian Ocean. been on the Pacific Ocean, and not the Indian Ocean. The Royal Australian Air Force has three air bases, two of David Brewster, writing for the Australian Strategic Policy which are in a maintained but inactive status in the north Institute, has highlighted the importance of the Indian coast area of Western Australia, and the other is a training Ocean as a waterway to world markets from the west and airfield shared with the Republic of Singapore Air Force northwest of the Australian continent. His article, entitled near Perth, which is on the southwest coast. Aside from “Australia’s Second Sea: Facing Our Multipolar Future in two training squadrons, there are no dedicated combat, the Indian Ocean,” exposes Australia’s national blindness early warning, maritime patrol or cargo aircraft based in to the importance of this ocean to the economy and secur- the region. -

EURASIA Black Sea Fleet Commander Takes Over Northern Fleet

EURASIA Black Sea Fleet Commander takes over Northern Fleet OE Watch Commentary: Vice Admiral Aleksandr Alexsanderevich Moiseev has been a fast-burner in the Russian submarine service and has spent much of that time beneath Arctic ice. He is no stranger to the Northern Fleet. Aside from the expected achievements of an up-and-coming submariner, in 1998, his submarine launched two German commercial satellites into orbit while submerged. It was the first commercial space launch for the Russian Navy and the first commercial payload launched from a submarine. His involvement in the November 2018 Kerch Strait incident has done nothing to slow down his meteoric career. As the accompanying passage from the Barents Sea Independent Observer discusses, he is replacing Nikolay Yevmenov, who is promoted to command the Russian Navy. End OE Watch Commentary (Grau) “Aleksandr Moiseev served 29 years onboard nuclear submarines. Now, he is the new commander in charge of Russia’s most powerful fleet.” Map of Russian Northern Fleet bases. Source: Kallemax at English Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Northern_Fleet_bases.png, Public domain Source: Atle Staalesen, “Putin appoints new leader of Northern Fleet,” Barents Sea Independent Observer, 8 May 2019. https:// thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2019/05/putin-appoints-new-leader-northern-fleet Putin appoints new leader of Northern Fleet The decree from President Vladimir Putin was signed on the 3rd of May. But the news was made public by the Armed Forces only six days later as thousands of Navy officers were marching in the streets on Victory Day May 9th. The person who has headed the Northern Fleet for the past three years, Nikolay Yevmenov, is promoted to command the Russian Navy. -

Confronting the Russian Challenge: a New Approach for the U.S

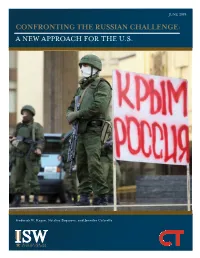

JUNE 2019 CONFRONTING THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE: A NEW APPROACH FOR THE U.S. Frederick W. Kagan, Nataliya Bugayova, and Jennifer Cafarella Frederick W. Kagan, Nataliya Bugayova, and Jennifer Cafarella CONFRONTING THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE: A NEW APPROACH FOR THE U.S. Cover: SIMFEROPOL, UKRAINE - MARCH 01: Heavily-armed soldiers without identifying insignia guard the Crimean parliament building next to a sign that reads: “Crimea Russia” after taking up positions there earlier in the day on March 1, 2014 in Simferopol, Ukraine. The soldiers’ arrival comes the day after soldiers in similar uniforms stationed themselves at Simferopol International Airport and Russian soldiers occupied the airport at nearby Sevastapol in moves that are raising tensions between Russia and the new Kiev government. Crimea has a majority Russian population and armed, pro-Russian groups have occupied government buildings in Simferopol. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images) All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing or from the publisher. ©2019 by the Institute for the Study of War and the Critical Threats Project. Published in 2019 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War and the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 1789 Massachusetts Avenue, NW | Washington, DC 20036 understandingwar.org criticalthreats.org ABOUT THE INSTITUTE ISW is a non-partisan and non-profit public policy research organization. -

Ukrainian President's Posts and Modern Political

Przegląd Strategiczny 2020, Issue 13 Nataliia STEBLYNA DOI : 10.14746/ps.2020.1.19 Pylyp Orlyk Institute for Democracy, Kyiv https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9799-9786 SELLING INSECURITY VIA TWITTER: UKRAINIAN PRESIDENT’S POSTS AND MODERN POLITICAL DISCOURSE War and military conflict have been effectively framed by politicians in the 21st century, beginning with the War on Terror (Entman, 2003). Social networks provide politicians with additional means to influence citizens’ attitudes towards war, and spread the politics of resentment (Fukuyama, 2018). There is thus a strong need to study politicians’ representations of war and conflicts on social networks on both aca- demic and media-critical levels. Modern scholars are deeply concerned about Trump’s Twitter case; Twitter, Fa- cebook and Instagram accounts of other Western leaders are also studied. However, political communication in the so-called developing countries isn’t so well-researched. Thus, quite different approaches towards communication via social networks may be discovered. Among these countries, Ukraine, – a post-Soviet state that faced annexa- tion and occupation of its territories, – is a particularly interesting one. In Ukraine, social networks, especially Russian Vkontakte, Facebook and Twitter, were employed as fields of harsh discussions, both for information and for propaganda spreading during the Euromaidan. Ukrainian and international politicians, experts, journalists, and activists were deeply involved in the discussion. As a result, many new charismatic leaders emerged, – such as officials elected to the Ukrainian parlia- ment – Verkhovna Rada – in 2015, – while others influenced Ukrainian politics as active members of civil society. The participation of American and Russian political technologists (Manafort, Surkov and others) increased the level of tensions, exploiting potentials of social networks to disseminate manipulative messages, fakes, calls to vio- lence; bot armies were also involved. -

Kerch Strait Incident

EaP Think №6 November, 2018 Bridge Eastern Partnership мonthly analytical digest Kerch Strait incident and its implications for regional security It would be easy to say that the whole situation in the Kerch Strait was just an overreaction of the Russian coastal guard, if not details of the attack and consequences of events EaP Think Bridge Issue 6 November, 2018 Is it time to worry? The incident in the Kerch Strait is a game changer in the Kremlin’s “hybrid” war. For the first time Russia openly attacked Ukraine, not hiding behind “polite green men” or “local protesters”. And this escalation is dangerous not only for Ukraine. EaP Think Bridge is a platform uniting expert Whether the security of the Eastern Partnership countries is threatened, which le- communities in the gal and political implications have been already caused by the aggression and which countries of Eastern are still getting underway, Hanna Shelest analyzed. Partnership region to Western politicians and world leading experts are already concerned about the fillthe gap in distributing security in the region. Thus, it is no coincidence that, first time ever, the Munich analytical products for Security Conference, the most authoritative international forum, held a meeting of stakeholders the Core Group in Eastern Europe. Whatthey discussed and, most importantly, what they failed to agree upon in Minsk, Yauheni Preiherman shared. And in the meantime Belarus itself arranged military cooperation and the supply of weapons to Azerbaijan. Concurrently, the rest of the region is still absorbed in the electoral process and has pushed security issues to the background. -

2:15-3:45 Security and Foreign Policy One of the Largest Challenges Ukraine's Next President Will Face Is the Security Of

2:15-3:45 Security and Foreign Policy One of the largest challenges Ukraine’s next president will face is the security of the country against Russian aggression. The 2018 Kerch Strait incident not only demonstrated the relentlessness of Russia’s continued incursions on Ukrainian sovereignty, but raised questions as to how Ukraine and the West should act in light of such attacks. Whoever wins the spring 2019 presidential elections will face important strategic decisions in the war effort and cooperation with international allies. This panel will be moderated by FSI Director and former Ambassador Michael McFaul. This discussion is designed to gather prominent voices in the foreign policy community in order to: ● Highlight Ukraine’s foreign policy priorities for the next five years; ● Position Ukraine within the larger geopolitical context; ● Demonstrate that Ukraine’s sovereignty is an international priority, especially in regards to European security. Dr. Michael Carpenter Senior Director of the Penn Biden Center Dr. Michael Carpenter is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. He is also senior director of the Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Carpenter is a former deputy assistant secretary of defense with responsibility for Russia, Ukraine, Eurasia, the Balkans, and Conventional Arms Control. Prior to joining the Department of Defense, Dr. Carpenter served in the White House as a foreign policy adviser to Vice President Joe Biden and as director for Russia at the National Security Council. Previously, he was a career foreign service officer with the State Department, where he worked in a number of different positions, including deputy director of the Office of Russian Affairs, speechwriter to the under-secretary of political affairs, and adviser on the South Caucasus. -

Drama in the Kerch Strait: Teasing the Russian Bear

Drama in the Kerch Strait: Teasing the Russian Bear By Pepe Escobar Region: Europe, Russia and FSU Global Research, November 28, 2018 Theme: Militarization and WMD, US NATO Asia Times 27 November 2018 War Agenda In-depth Report: UKRAINE REPORT When the Ukrainian navy sent a tugboat and two small gunboats on Sunday to force their way through the Kerch Strait into the Sea of Azov, it knew in advance the Russian response would be swift and merciless. After all, Kiev was entering waters claimed by Russia with military vessels without clarifying their intent. The intent, though, was clear; to raise the stakes in the militarization of the Sea of Azov. The Kerch Strait connects the Sea of Azov with the Black Sea. To reach Mariupol, a key city in the Sea of Azov very close to the dangerous dividing line between Ukraine’s army and the pro-Russian militias in Donbass, the Ukrainian navy needs to go through the Kerch. Yet since Russia retook control of Crimea via a 2014 referendum, the waters around Kerch are de facto Russian territorial waters. Kiev announced this past summer it would build a naval base in the Sea of Azov by the end of 2018. That’s an absolute red line for Moscow. Kiev may have to trade access to Mariupol, which, incidentally, also trades closely with the People’s Republic of Donetsk. But forget about military access. And most of all, forget about supplying a Ukrainian military fleet in the port of Berdyansk capable of sabotaging the immensely successful, Russian-built Crimean bridge. -

Jemadu, Aleksius “Realisme Sebagai Teori Dan Penerapannya.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY Books : Jemadu, Aleksius “Realisme Sebagai Teori dan Penerapannya.” (Realism as Theory and its Practice) In Politik Global Dalam Teori dan Praktik (Global Politics in Theory and Practice), 20-35, Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Suluh Media, 2017 Kamasa, Frassminggi. “EKONOMI, KEUANGAN, DAN PERBANKAN RUSIA” (Russia’s Economy, Finance, and Banking). In POLITIK dan EKONOMI RUSIA Selepas Komunisme (Russian Post-Communism Politics and Economy) , 147-182. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Calpulis. 2016 Kuzion, Taras and D’Anieri, Paul. “Annexation and Hybrid Warfare in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine”. In The Sources of Russia’s Great Power Politics, 86-113. Bristol, England: E-International Relations Publishing, 2018 Marples, David R. “Crimea: Recapping Five Months of Change in Ukraine.” In Ukraine in Conflict: An Analytical Chronicle, 41-46. Bristol, England: E- International Relations Publishing, 2017 Marples, David R. “Ethnic and Social of Ukraine’s Regions and Voting Patterns.” In Ukraine in Conflict: An Analytical Chronicle, 122-130. Bristol, England: E-International Relations Publishing, 2017 Menon, Rajan, and Rumer, Eugene B.. 2015. “Ukraine’s Prospects” In Conflict in Ukraine : The Unwinding of the Post--Cold War Order. 145-155 Cambridge: MIT Press. Accessed May 1, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central. Morgenthau, Hans J. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle For Power and Peace fifth edition, revised. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc, 1978. Neuman, W. Lawrence. Social Research Methods: Qualitative And Quantitative Approaches. 7th ed. Pearson. 2013 Rutland, Peter. “An Unnecessary War: The Geopolitical Roots of the Ukraine Crisis.” In Ukraine and Russia People, Politics, Propaganda, and Perspectives, edited by Agniezka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Richard Sakwa, 122-133. Bristol, England: E-International Relations Publishing, 2016 Uehling, Greta. -

The Kremlin's Malign Legal Operations on the Black Sea

The Kremlin’s Malign Legal Operations on the Black Sea: Analyzing the Exploitation of Public International Law Against Ukraine Author(s): Brad Fisher Source: Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal 5 (2019): 193–223 Published by: National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy http://kmlpj.ukma.edu.ua/ The Kremlin’s Malign Legal Operations on the Black Sea: Analyzing the Exploitation of Public International Law Against Ukraine Brad Fisher PhD Student, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Ukraine Major, United States Air Force The views expressed are written solely in the author’s personal capacity and do not represent those of the United States government or National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in any capacity. Abstract This article seeks to analyze the asymmetric manipulation and exploitation of legal domains to achieve political objectives. A multidisciplinary analysis is offered to explore the perversion of the law to shape legitimacy, contain adversaries, justify violations, escape obligations, and ultimately to advantageously revise the international and domestic rule of law. Colloquially known as lawfare, this article offers a discourse analysis of the term and asserts that a more doctrinally appropriate phrase exists to describe this phenomenon; Malign Legal Operations (MALOPs). Furthermore, this article asserts that MALOPs are the root of contemporary hybrid warfare and that all other hybrid means are secondary. In particular, the Russian Federation’s behavior towards Ukraine in the Black Sea region is used as a case study to determine the extent of these MALOPs and to explore what measures can be taken to defend the rule of law. The primary example offered is Russia’s November 25th, 2018 attack on three Ukrainian Naval vessels in the Kerch Strait and its capture of 24 sailors. -

Security & Defence

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE CONTENT π 1-2 (177-178) THE WAR IN DONBAS: REALITIES AND PROSPECTS OF SETTLEMENT ................2 2019 1. GEOPOLITICAL ASPECTS OF CONFLICT IN DONBAS ............................................3 Founded and published by: 1.1. Russia’s “hybrid” aggression: geopolitical dimension ................................................ 3 1.2. Russian intervention in Donbas: goals and specifics .................................................. 6 1.3. Role and impact of the West in settling the conflict in Donbas .................................12 1.4. Ukraine’s policy for Donbas ......................................................................................24 2. OCCUPATION OF DONBAS: CURRENT SITUATION AND TRENDS ........................35 UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES 2.1. Military component of Donbas occupation ...............................................................35 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV 2.2. Socio-economic situation in the occupied territories ................................................42 Director General Anatoliy Rachok 2.3. Energy aspect of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine .......................................................50 Editor-in-Chief Yuriy Yakymenko 2.4. Ideology and information policy in “DPR-LPR” .........................................................56 2.5. Environmental situation in the occupied territories ...................................................62 Editor Hanna Pashkova 3. DONBAS: SCENARIOS OF DEVELOPMENTS Halyna Balanovych AND PROSPECTS -

The Black Sea Kerch Strait Incident: Between Maritime Law and Psychology Drama Triangle 2021

Critical Rethinking of Public Administration Contribution ID: 46 Típus: International Studies The Black Sea Kerch Strait Incident: Between Maritime Law and Psychology Drama Triangle 2021. április 10., szombat 12:00 (15 perc) This empirical study addresses the reasons behind differing interpretations of international rules intheas- sessment of the 2018 Kerch Strait incident, in which Russian vessels implemented military action towards Ukrainian vessels. The article is significant, because it concerns the EU neighbourhood, Russia-NATO dynam- ics, the role of Turkey, and Ukraine. The first perspective explores the challenges of the Black Sea maritime security in the framework of UN Law of the Sea 1982 and the Montreux Convention 1936. The findings show that the Kerch Strait Incident could be solved according to the international law only if the law is accepted by all involved states. The major difficulty comes from the interpretation of Russia, as the control oftheKerch Strait allows access of NATO to its internal territory through Azov Sea, endangering its internal security. The territorial waters of Crimea refer to its land, therefore Kerch can be judged only after agreement to whom Crimea belongs through political agreement or through new maritime law. The second perspective examines psychology drama triangle, where the long-lasting historical competition over Crimea moves between victim- villain-rescuer triangle. In this case, it is found that the core problem is Ukraine’s role of a victim who changes its perception to different actors over time, seeing them once as rescuers, second time as villains. Therefore, the solution is in assuring constant and stable policy of Ukraine. -

H. Res. 755, Articles of Impeachment Against President Donald J. Trump Volume Xi

MARKUP OF: H. RES. 755, ARTICLES OF IMPEACHMENT AGAINST PRESIDENT DONALD J. TRUMP VOLUME XI HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DECEMBER 11–13, 2019 Serial No. 116–69 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available http://judiciary.house.gov or www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 39–411 WASHINGTON : 2020 VerDate Sep 11 2014 18:18 Jan 21, 2020 Jkt 039411 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\39411P1.XXX 39411P1 tkelley on DSKBCP9HB2PROD with HEARING COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JERROLD NADLER, New York, Chairman ZOE LOFGREN, California DOUG COLLINS, Georgia, Ranking Member SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., STEVE COHEN, Tennessee Wisconsin HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas KAREN BASS, California JIM JORDAN, Ohio CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana KEN BUCK, Colorado HAKEEM S. JEFFRIES, New York JOHN RATCLIFFE, Texas DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island MARTHA ROBY, Alabama ERIC SWALWELL, California MATT GAETZ, Florida TED LIEU, California MIKE JOHNSON, Louisiana JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland ANDY BIGGS, Arizona PRAMILA JAYAPAL, Washington TOM MCCLINTOCK, California VAL BUTLER DEMINGS, Florida DEBBIE LESKO, Arizona J. LUIS CORREA, California GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania MARY GAY SCANLON, Pennsylvania, BEN CLINE, Virginia Vice-Chair KELLY ARMSTRONG, North Dakota SYLVIA R. GARCIA, Texas W. GREGORY STEUBE, Florida JOE NEGUSE, Colorado LUCY MCBATH, Georgia GREG STANTON, Arizona MADELEINE DEAN, Pennsylvania DEBBIE MUCARSEL-POWELL, Florida VERONICA ESCOBAR, Texas PERRY APELBAUM, Majority Staff Director & Chief Counsel BRENDAN BELAIR, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 18:18 Jan 21, 2020 Jkt 039411 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 E:\HR\OC\39411P1.XXX 39411P1 tkelley on DSKBCP9HB2PROD with HEARING C O N T E N T S VOLUME XI DECEMBER 11–13, 2019 A.