A Feminist Analysis of Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gone with the Wind

Gone With The Wind by Margaret Mitchell STYLED BY LIMPIDSOFT Contents PART ONE4 CHAPTER I.................... 5 CHAPTER II.................... 42 CHAPTER III................... 77 CHAPTER IV................... 119 CHAPTER V.................... 144 CHAPTER VI................... 180 CHAPTER VII................... 248 PART TWO 266 CHAPTER VIII.................. 267 CHAPTER IX................... 305 CHAPTER X.................... 373 CHAPTER XI................... 397 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER XII................... 411 CHAPTER XIII.................. 448 CHAPTER XIV.................. 478 CHAPTER XV................... 501 CHAPTER XVI.................. 528 PART THREE 547 CHAPTER XVII.................. 548 CHAPTER XVIII................. 591 CHAPTER XIX.................. 621 CHAPTER XX................... 650 CHAPTER XXI.................. 667 CHAPTER XXII.................. 696 CHAPTER XXIII................. 709 CHAPTER XXIV................. 746 CHAPTER XXV.................. 802 CHAPTER XXVI................. 829 CHAPTER XXVII................. 871 CHAPTER XXVIII................ 895 CHAPTER XXIX................. 926 CHAPTER XXX.................. 952 3 CONTENTS PART FOUR 983 CHAPTER XXXI................. 984 CHAPTER XXXII................. 1017 CHAPTER XXXIII................ 1047 CHAPTER XXXIV................ 1076 CHAPTER XXXV................. 1117 CHAPTER XXXVI................ 1164 CHAPTER XXXVII................ 1226 CHAPTER XXXVIII............... 1258 CHAPTER XXXIX................ 1311 CHAPTER XL................... 1342 CHAPTER XLI.................. 1377 CHAPTER -

Gone with the Wind Part 1

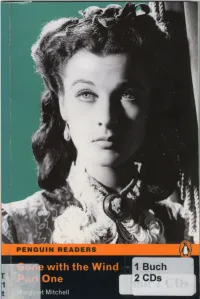

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Museum of History and Holocaust Education Legacy Series Jean Ousley Interview Conducted by Adina Langer January 29, 2018 Transcribed by Adina Langer

Museum of History and Holocaust Education Legacy Series Jean Ousley Interview Conducted by Adina Langer January 29, 2018 Transcribed by Adina Langer Born in 1945, Jean Ousley met her father for the first time after he returned from service in World War II. Her mother worked at the Kellogg Plant in Battle Creek, Michigan, and then as a welder at a factory in California. As an adult, Ousley led the Georgia chapter of the American Rosie the Riveter Association because of her mother’s contributions to the war effort. Full Transcript Interviewer: Today is January 29, 2018. My name is Adina Langer, and I'm the curator of the Museum of History and Holocaust Education at Kennesaw State University, and I'm here at the Sturgis Library with Jean Ousley. First of all, do you agree to this interview? Ousley: Yes, absolutely. Interviewer: Could you please state your full name? Ousley: Interesting, because I told you I'm Jean, but remember, my story is that I'm Gloria Jean. I was named because my grandmother wanted my name to be Gloria, but then I think my mother was trying to exert her independence, and she never called me Gloria. So Jean is—Gloria Jean Spriggs Ousley. Interviewer: OK. And what's your birthday? Ousley: April 22, 1945. Interviewer: And where were you born? Ousley: I was born in Gainesville in the Hall County Hospital in Gainesville, Georgia. Interviewer: So, before we talk about your childhood, I'd like to go back a bit further and talk about your parents. What were your parents' names? Ousley: My father was Samuel Eldo Spriggs—the middle name kind of unusual—from basically Gwinnett County, Georgia, I guess. -

Gone with the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy

Gone With the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy (Tara is the beautiful homeland of Scarlett, who is now talking with the twins, Brent and Stew, at the door step.) BRENT What do we care if we were expelled from college, Scarlett. The war is going to start any day now so we would have left college anyhow. STEW Oh, isn't it exciting, Scarlett? You know those poor Yankees actually want a war? BRENT We'll show 'em. SCARLETT Fiddle-dee-dee. War, war, war. This war talk is spoiling all the fun at every party this spring. I get so bored I could scream. Besides, there isn't going to be any war. BRENT Not going to be any war? STEW Ah, buddy, of course there's going to be a war. SCARLETT If either of you boys says "war" just once again, I'll go in the house and slam the door. BRENT But Scarlett honey.. STEW Don't you want us to have a war? BRENT Wait a minute, Scarlett... STEW We'll talk about this... BRENT No please, we'll do anything you say... SCARLETT Well- but remember I warned you. BRENT I've got an idea. We'll talk about the barbecue the Wilkes are giving over at Twelve Oaks tomorrow. STEW That's a good idea. You're eating barbecue with us, aren't you, Scarlett? SCARLETT Well, I hadn't thought about that yet, I'll...I'll think about that tomorrow. STEW And we want all your waltzes, there's first Brent, then me, then Brent, then me again, then Saul. -

Cottonwood Estates

255 Vaughan Drive • Alpharetta, GA 30009 • Phone (678) 242-0334 • www.seniorlivinginstyle.com JUNE 2021 Men’s Breakfast Group Outing COTTONWOOD ESTATES STAFF On June 16th, our Men’s Breakfast Managers ............. CHRIS & SALLY BLANCHARD Group that meets Executive Chef ........................ JONATHAN ELAM once a month for Marketing ..................................SEÃN JOHNSON coffee and breakfast Activity Coordinator .................... JOHN CARSON is finally going out Maintenance ������������������������������� MARK SIMMS for a field trip and Transportation ......................... THOMAS BABER breakfast. It has been a long-time coming. After spending lots of time reviewing and TRANSPORTATION researching several Monday, 9:30 a.m.: Windward Pkwy. Shopping places to go for the Monday, 2 p.m.: Windward Pkwy. Shopping outing, a decision was made. Drum roll, please! John, the Tuesday, 9 a.m.-2 p.m.: Doctor Appointments Activity Coordinator, decided to take our Men’s Breakfast Wednesday, 10:30 a.m.: Outing Group for hearty breakfast at the Red Eyed Mule, which Thursday, 9 a.m.-2 p.m.: Doctor Appointments is a local favorite of the residents of Kennesaw, Georgia. Friday, 9:30 a.m. .: Northpoint Pkwy. Shopping After breakfast, the men will be treated to visiting The Friday, 2 p.m.: Northpoint Pkwy. Shopping Southern Museum of the Civil War and Locomotive History in old town Kennesaw, Georgia. The men will have the opportunity to look over a significant collection of company records, engineering drawings, blueprints, glass plate negatives, photographs and correspondence from various American businesses representing the railroad industry in the South after the Civil War. Also, they can look over a major collection of Civil War letters, diaries, and official records from that time period. -

Thematic Analysis of Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.7 Issue 1 An International Peer Reviewed (Refereed) Journal 2020 Impact Factor (SJIF) 4.092 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE THEMATIC ANALYSIS OF MARGARET MITCHELL’S GONE WITH THE WIND Mrs.P.Rajisha Menon (Assistant Professor-in-English, CVR College of Engineering, Humanities and Social Sciences (English), Hyderabad, India.) Email:[email protected] DOI: 10.333329/joell.7.1.62 ABSTRACT Gone with the Wind written by Margaret Mitchell illustrates the aftermath effects of the Civil War. The protagonist is Scarlett O’Hara, who victoriously survives the war. She is a gorgeous girl in the area. She is in love with Ashley Wilkes. She loses temper when she comes to know that he is going to marry his cousin Melanie Hamilton. As a vendetta she decides to marry Melanie’s brother. The effect of war is severe. Men go to the battle thinking that it will only last a few weeks but continue for a longer period of time. Scarlett who is living in Atlanta witnesses the ravages that war brings. She also gets reacquainted with Rhett Butler, whom she had first met at the Wilkes barbecue. Though a widow, she still strives to get the attention of the married Ashley and dreams of his return. They lose the civil war and she is compelled to return to Tara and experiences the hardship of keeping her family together and Tara, the plantation from being sold. She is hardened and bitter with the circumstances which she faces. There is a drastic transformation in her. -

November – December 13

VOLUME XXVII—NUMBER XI I Official Publication of the Georgia Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans November / December 2013 Confederacy. ANNUAL GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE Immediately following the program, the first Ex- ecutive Council meeting of the calendar year will be COMMEMORATIVE EVENT held, all are invited to attend. The posters for April January 18, 2014 at 10:30 am depicting the year of 1864 with GA in the cross hairs The Gen. Robert E. Lee of the War will be available. We need to get them in Birthday Commemorative is the schools and libraries around the Division, often scheduled for Jan. 18, 2014 at times this is the only time the students will be exposed the Old Capitol Building, 201 to the truth about the War. So come pick yours up, we E. Greene St., Milledgeville, need to attempt to get these out and into places where the public and especially the youth can see and read at GA. The parade route will as- least a little about the real reasons and consequences semble at 10:30 a.m. at the Old of the War of Northern Aggression. Governor's Mansion on W. Hancock Street and proceed We enter a new year, 2014, 150 years ago the War through downtown to the Old started its march to Georgia, the early months were Capitol on East Greene St. Commander's Report. somewhat quiet in our home state but the dark cloud Those able to march in the of Billy the Torch was on its way. Take time this year Greetings my fellow Compatriots, parade are asked to dress ac- to remember the civilians, men, women, children, cordingly (uniform, period young and old, of all races who were to fall at the I hope you all had a very Merry dress preferred but not neces- hands of the dreaded yankee. -

Gone with the Wind – Part Two Book Key D Some Negro Men Are Rude and Insulting to White 1 a Blockader, Convict, Confederate, Mammy, Negro, Pa, People

LEVEL 4 Answer keys Teacher Support Programme Gone With The Wind – Part Two Book key d Some negro men are rude and insulting to white 1 a blockader, convict, confederate, Mammy, negro, Pa, people. prostitute, slave, trash, Yankee e Rhett Butler is in prison for killing a negro. He has b carriage, wagon stolen some confederate money. c cheek, nail 7 She visits Rhett in prison, telling him everything is fine 2 a Scarlett has lost her husband and friends in the civil in Tara. Everything is not fine in Tara and she actually war. She has to pay high taxes to Northerners. She wants Rhett’s money. is clever, strong and independent. Scarlett wants 8–9 open answers Ashley, but he does not love her. Rhett is handsome, 10 a F dangerous, wealthy and rich. Melanie is a loyal friend b T to Scarlett. c T b Before the war, negro slaves had been made to d T work hard for rich white plantation owners. At e F the end of the civil war, negro slaves were freed. 11 a hang However, many negroes did not know how to live b dishonest as free men so they continued to work as before. c Suellen Negroes were often threatened by the Ku Klux Klan. d Yankees c Carpetbaggers were men who came from the e sign North. They came south to demand money from 12 a Scarlett marries him because he has wealth and can southerners or buy their land cheaply. provide opportunities to make more money. d The northern Yankees beat the southerners in the b Scarlett didn’t realise that Rhett was very wealthy civil war. -

Gone with the Wind Is Di Smissed by Many Critics As a Racist Film, and Therefore, Unworthy of Discussion

A N I L L U M I N E D I L L U S I O N S E S S A Y B Y I A N C . B L O O M GG OO NN EE WW II TT HH TT HH EE WW II NN DD Directed by Victor Fleming Produced by David O. Selznick Distributed by Metro - Goldwyn - Mayer Released in 1939 ead a different dictionary, get a different definition of racism. Variously, it could be (and R is) defined as a p rejudice of dislike/disdain/distrust against a person of a particular race, because of his race and not the person, himself. Or it is reckoned to be manifested in one person's dislike/disdain/distrust of another person even though the object - person's race is not a contributing factor to the supposed - bigot's view. Alternatively, it could be discerned in the words of a person who is making a sweeping statement attributing to a race of people a defining or frequently - observed characteristic (even if positive ). Or, an accusation of racism need not, perhaps, be justified at all; it is merely the 'gotcha' word that wins an argument by default. For if the speaker is successfully maligned, his argument will be dismissed out of hand. Gone With The Wind is di smissed by many critics as a racist film, and therefore, unworthy of discussion. Given that neither blacks, slavery, nor emancipation are a central focus of the film, it is difficult to describe the entire production as racist. However, the film may very well betray racist tendencies in how it handles — or ignores — black characters. -

Plot Overview

Plot Overview It is the spring of 1861. Scarlett O’Hara, a pretty Southern belle, lives on Tara, a large plantation in Georgia. She concerns herself only with her numerous suitors and her desire to marry Ashley Wilkes. One day she hears that Ashley is engaged to Melanie Hamilton, his frail, plain cousin from Atlanta. At a barbecue at the Wilkes plantation the next day, Scarlett confesses her feelings to Ashley. He tells her that he does love her but that he is marrying Melanie because she is similar to him, whereas he and Scarlett are very different. Scarlett slaps Ashley and he leaves the room. Suddenly Scarlett realizes that she is not alone. Rhett Butler, a scandalous but dashing adventurer, has been watching the whole scene, and he compliments Scarlett on being unladylike. The Civil War begins. Charles Hamilton, Melanie’s timid, dull brother, proposes to Scarlett. She spitefully agrees to marry him, hoping to hurt Ashley. Over the course of two months, Scarlett and Charles marry, Charles joins the army and dies of the measles, and Scarlett learns that she is pregnant. After Scarlett gives birth to a son, Wade, she becomes bored and unhappy. She makes a long trip to Atlanta to stay with Melanie and Melanie’s aunt, Pittypat. The busy city agrees with Scarlett’s temperament, and she begins to see a great deal of Rhett. Rhett infuriates Scarlett with his bluntness and mockery, but he also encourages her to flout the severely restrictive social requirements for mourning Southern widows. As the war progresses, food and clothing run scarce in Atlanta. -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE GUMBO BANAHA STORIES: LOUISIANA INDIGENIETIES AND THE TRNASNATIONAL SOUTH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By LETHA RAIN ALICIA CRANFORD-GOMÉZ Norman, Oklahoma 2014 GUMBO BANAHA STORIES: LOUISIANA INDIGENITIES AND THE TRANSNATIONAL SOUTH A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY ______________________________ Dr. Geary Hobson, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Kimberly Roppolo ______________________________ Dr. Joshua Nelson ______________________________ Dr. Rhonda Harris Taylor ______________________________ Dr. Andrew Jolivétte © Copyright by LETHA RAIN ALICIA CRANFORD GOMÉZ 2014 All Rights Reserved. This dissertation is dedicated to the Indigenous Peoples of Louisiana be they federally recognized, state recognized, or struggling for recognition… The completing of writing of a dissertation is a community-building activity. It is assuredly an act of cooperation, negotiation, and family-making. My ability to weave from a multiplicity of communities, to make meaning from them in languages known, forgotten, alphanumerical, sung, tactile, material, and silenced would not be possible without the people and communities that have surrounded me. These people have come together from academia, homespaces, Gulf-shores, bayous, prairies, Southern plains, Pacific coasts (from the relocation diaspora), Great Lakes, and in the whispered words of memory (from ancestors who have walked on). I take this time to thank them now. Dr. Geary Hobson, my professor, mentor, and dissertation chair, your encouragement and support has meant the world to me. You are a living legend in American Indian literature as a literary critic and an author, as well as a molder of academics and creative writers. -

MARGARET MITCHELL: a LINK to ATLANTA and the WORLD a Teacher’S Guide to the Author of Gone with the Wind MARGARET MITCHELL: a LINK to ATLANTA and the WORLD

MARGARET MITCHELL: A LINK TO ATLANTA AND THE WORLD A Teacher’s Guide to the Author of Gone With the Wind MARGARET MITCHELL: A LINK TO ATLANTA AND THE WORLD TITLE PAGE . 2 COPYRIGHT PAGE . 3 WELCOME . 4 MUSEUM GOALS & EDUCATION OBJECTIVES. 5 PART I – MARGARET MITCHELL: HER EARLY YEARS. 6 PART II – MARGARET MITCHELL: JOURNALISM CAREER . 12 PART III – WRITING THE NOVEL GONE WITH THE WIND . 18 PART IV – MARGARET MITCHELL: HER LATER YEARS . .23 PART V – THE MOVIE GONE WITH THE WIND . 28 PART VI – THE MARGARET MITCHELL HOUSE – 17 CRESCENT AVENUE . 32 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 36 Cover image: Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center 1 MARGARET MITCHELL: A LINK TO ATLANTA AND THE WORLD A Teacher’s Guide to the Author of Gone With the Wind Anita P. Davis The Charles A. Dana Professor of Education Converse College Spartanburg, South Carolina 2 COPYRIGHT 2006 The Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. Margaret Mitchell House and The Atlanta History Center This publication was made possible through a grant from Barnes and Noble, and with assistance from Converse College, Spartanburg, South Carolina, and support from the Margaret Mitchell House, Atlanta, Georgia. 3 WELCOME TO THE MARGARET MITCHELL HOUSE CURRICULUM GUIDE Author: Anita Price Davis Editors and Contributors: Julie Bookman, Karen Kelly, Mary Wilson, and Bonnie Garvin Designer: Barry Watts Dear Educator: The Atlanta History Center and the Margaret Mitchell House hope you will enjoy and use this guide to the working life of Margaret Mitchell and the residence in which she lived while writing the 1936 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Gone With the Wind.