American Traditional Music in Max Steiner's Score for Gone with the Wind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Joy Harjo Reads from 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library

Joy Harjo Reads From 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library [0:00:05] Podcast Announcer: Welcome to the Seattle Public Library's podcasts of author readings and Library events; a series of readings, performances, lectures and discussions. Library podcasts are brought to you by the Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts visit our website at www.spl.org. To learn how you can help the Library Foundation support the Seattle Public Library go to foundation.spl.org. [0:00:40] Marion Scichilone: Thank you for joining us for an evening with Joy Harjo who is here with her new book Crazy Brave. Thank you to Elliot Bay Book Company for inviting us to co-present this event, to the Seattle Times for generous promotional support for library programs. We thank our authors series sponsor Gary Kunis. Now, I'm going to turn the podium over to Karen Maeda Allman from Elliott Bay Book Company to introduce our special guest. Thank you. [0:01:22] Karen Maeda Allman: Thanks Marion. And thank you all for coming this evening. I know this is one of the readings I've most look forward to this summer. And as I know many of you and I know that many of you have been reading Joy Harjo's poetry for many many years. And, so is exciting to finally, not only get to hear her read, but also to hear her play her music. Joy Harjo is of Muscogee Creek and also a Cherokee descent. And she is a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa. -

A Study on Scarlet O' Hara's Ambitions in Margaret Mitchell's Gone

Chapter 3 The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions and Her Ways to Obtain Them I begin the analysis by revealing the factors of O’Hara’s two ambitions, namely the willingness to rebuild Tara and the desire to win Wilkes’ love. I divide this chapter into two main subchapters. The first subchapter is about the factors of the two ambitions that Scarlett O’Hara has, whereas the second subchapter explains how she tries to accomplish those ambitions. 3.1. The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions The main female character in Gone with the Wind has two great ambitions; her desires to preserve the family plantation called Tara, and to win Ashley Wilkes’ love by supporting his family’s needs. Scarlett O’Hara herself confesses that “Every part of her, almost everything she had ever done, striven after, attained, belonged to Ashley, were done because she loved him. Ashley and Tara, she belonged to them” (Mitchell, 1936, p.826). I am convinced that there are many factors which stimulate O’Hara to get these two ambitions. Thus, I use the literary tools: the theories of characterization, conflict and setting to analyze the factors. 3.1.1. The Ambition to Preserve Tara Scarlett O’Hara’s ambition to preserve the family’s plantation is stimulated by many factors within her life. I divide the factors that incite Scarlett O’Hara’s ambitions into two parts, the factors found before the war and after. The factors before the war are the sense of belonging to her land, the Southern tradition, and Tara which becomes the source of income. -

VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 MARCH—MAY, 2010 IRISHMAN of the YEAR the Louisiana State Board of Federal Narcotics Enforcement the Ancient Order of Hiber- Taskforce

THE CRESCENT HARP THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN LOUISIANA VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 MARCH—MAY, 2010 IRISHMAN OF THE YEAR The Louisiana State Board of Federal Narcotics Enforcement the Ancient Order of Hiber- taskforce. Upon his retire- nians, Philip M. Hannan, Car- ment from the Police Depart- dinal Gibbons, Acadian, and ment, he has continued to Republic of West Florida Divi- serve on the board of the Po- sions proudly announce Joseph lice Federal Credit Union. James Cronin Sr. as Irishman Cronin is a member of the of the Year for 2010. A re- Veterans of Foreign Wars Post FOLLOW THE LOUISIANA tired longshoreman and vet- 6640 and American Legion AOH ON-LINE eran of the New Orleans Po- Post 267. He is a parishioner www.aohla.com lice Department, Brother Cro- at St. Benilde Church in Met- FACEBOOK nin was born in New Orleans airie where he was recently Louisiana State Board of in 1924, the son of the late honoured as a senior great- the Ancient Order of Hibernians Michael R. Cronin and Alice grandfather. McMullen Cronin. A native of Cronin was married to the UPCOMING EVENTS: the Irish Channel, he attended Navy Seabees from 1943-46. late Hilda Conzonire Cronin Redemptorist School and is a Upon his return from the from 1942 to 1960 and is cur- Irish Channel 1943 graduate of St. Aloysius war, Cronin joined the Clerks rently married to the former St. Patrick’s Day High School where he was Local Longshoreman’s Union Judy Whitney since 1963. He Mass and Parade named second team All-Prep Number 1497 and then gradu- is the father of six children, SATURDAY, MARCH 13 as a member of the football ated from the New Orleans twelve grandchildren, and two 12 noon team. -

MUSIC and MOVEMENT in PIXAR: the TSU's AS an ANALYTICAL RESOURCE

Revis ta de Comunicación Vivat Academia ISSN: 1575-2844 Septiembre 2016 Año XIX Nº 136 pp 82-94 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2016.136.82-94 INVESTIGACIÓN/RESEARCH Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 MUSIC AND MOVEMENT IN PIXAR: THE TSU’s AS AN ANALYTICAL RESOURCE Diego Calderón Garrido1: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Josep Gustems Carncier: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Jaume Duran Castells: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] ABSTRACT The music for the animation cinema is closely linked with the characters’ movement and the narrative action. This paper presents the Temporary Semiotic Units (TSU’s) proposed by Delalande, as a multimodal tool for the music analysis of the actions in cartoons, following the tradition of the Mickey Mousing. For this, a profile with the applicability of the nineteen TSU’s was applied to the fourteen Pixar movies produced between 1995-2013. The results allow us to state the convenience of the use of the TSU’s for the music comprehension in these films, especially in regard to the subject matter and the characterization of the characters and as a support to the visual narrative of this genre. KEY WORDS Animation cinema, Music – Pixar - Temporary Semiotic Units - Mickey Mousing - Audiovisual Narrative – Multimodality 1 Diego Calderón Garrido: Doctor in History of Art, titled superior in Modern Music and Jazz music teacher and sound in the degree of Audiovisual Communication at the University of Barcelona. -

Academy Committees 19~5 - 19~6

ACADEMY COMMITTEES 19~5 - 19~6 Jean Hersholt, president and Margaret Gledhill, Executive Secretary, ex officio members of all committees. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE SPECIAL DOCUMENTARY Harry Brand COMMITTEE lBTH AWARDS will i am Do z i e r Sidney Solow, Chairman Ray Heindorf William Dozier Frank Lloyd Philip Dunne Mary C. McCall, Jr. James Wong Howe Thomas T. Moulton Nunnally Johnson James Stewart William Cameron Menzies Harriet Parsons FINANCE COMMITTEE Anne Revere Joseph Si strom John LeRoy Johnston, Chairman Frank Tuttle Gordon Hollingshead wi a rd I h n en · SPECIAL COMMITTEE 18TH AWARDS PRESENTATION FILM VIEWING COMMITTEE Farciot Edouart, Chairman William Dozier, Chairman Charles Brackett Joan Harrison Will i am Do z i e r Howard Koch Hal E1 ias Dore Schary A. Arnold Gillespie Johnny Green SHORT SUBJECTS EXECUTIVE Bernard Herzbrun COMMI TTEE Gordon Hollingshead Wiard Ihnen Jules white, Chairman John LeRoy Johnston Gordon Ho11 ingshead St acy Keach Walter Lantz Hal Kern Louis Notarius Robert Lees Pete Smith Fred MacMu rray Mary C. McCall, Jr. MUSIC BRANCH EXECUTIVE Lou i s Mesenkop COMMITTEE Victor Milner Thomas T. Moulton Mario Caste1nuovo-Tedesco Clem Portman Adolph Deutsch Fred Ri chards Ray Heindorf Frederick Rinaldo Louis Lipstone Sidney Solow Abe Meyer Alfred Newman Herbert Stothart INTERNATIONAL AWARD Ned Washington COMM I TTEE Charles Boyer MUSIC BRANCH HOLLYWOOD Walt Disney BOWL CONCERT COMMITTEE wi 11 i am Gordon Luigi Luraschi Johnny Green, Chairman Robert Riskin Adolph Deutsch Carl Schaefer Ray Heindorf Robert Vogel Edward B. Powell Morris Stoloff Charles Wolcott ACADEMY FOUNDATION TRUSTEES Victor Young Charles Brackett Michael Curtiz MUSIC BRANCH ACTIVITIES Farc i ot Edouart COMMITTEE Nat Finston Jean Hersholt Franz Waxman, Chairman Y. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

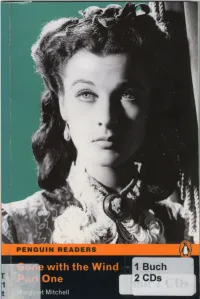

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Youth Musical Theater Company

Youth Musical Theater Company FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Inquiries: Laura Soble/YMTC Phone: 510-847-6128 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ymtcbayarea.org (media resources) YMTC TO STAGE GUYS & DOLLS, NOVEMBER 4-12, IN EL CERRITO Berkeley, California. September 12, 2017—YMTC (Youth Musical Theater Company) opens its 13th season with the celebrated musical comedy, Guys and Dolls. Set in Damon Runyon’s mythical New York City, it tells the story of gambler Nathan Detroit, his long- time girlfriend Adelaide, fellow gambler Sky Masterson, and strait-laced missionary Sarah Brown. The show moves from the heart of Times Square to the cafes of Havana, and even into the sewers of New York City. But eventually everyone ends up right where they belong. Frank Loesser’s bold, brassy songs light up this hilarious romp, populated by memorable characters with good intentions and hearts of gold. Guys and Dolls opens Saturday, November 4, at El Cerrito High School Performing Arts Theater, 540 Ashbury Avenue, El Cerrito, and runs for two weekends. Performances include three matinees at 2:00 p.m. on 11/5, 11/11, and 11/12 and three evening performances at 7:30 p.m. on 11/4, 11/10, and 11/11. Tickets are available online at www.ymtcbayarea.org or at the door one hour before curtain. Ticket prices are $15–$28, with discounts for students, seniors, military, teachers, and groups. Subscriptions to all four shows in YMTC’s 13th season at the El Cerrito High School Performing Arts Theater can also be purchased online. In addition to Guys and Dolls, the season includes A Chorus Line, Next to Normal, and Parade. -

Narcocorridos As a Symptomatic Lens for Modern Mexico

UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Vol. 1, No. 2 “Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro “The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic Fetishism and Fan Engagement with and Anthropological Lens to the War Horror Scores” on Drugs in Mexico” Spencer Slayton Samantha Cabral “Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s “This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Extremity in Thomas Adès’s The Acceptance in Shrek the Musical” Exterminating Angel” Clarina Dimayuga Lori McMahan “Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema” Liv Slaby Spring 2020 Editor-in-Chief J.W. Clark Managing Editor Liv Slaby Review Editor Gabriel Deibel Technical Editors Torrey Bubien Alana Chester Matthew Gilbert Karen Thantrakul Graphic Designer Alexa Baruch Faculty Advisor Dr. Elisabeth Le Guin 1 UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1, Number 2 Spring 2020 Contents Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement 2 with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s Extremity in Thomas Adès’s 10 The Exterminating Angel Lori McMahan The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic and Anthropological Lens to 18 the War on Drugs in Mexico Samantha Cabral This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Acceptance in Shrek the 28 Musical Clarina Dimayuga Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema 38 Liv Slaby Contributors 50 Closing notes 51 2 Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton he horror genre is in the midst of a renaissance. The slasher craze of the late 70s and early 80s, revitalized in the mid-90s, is once again a popular genre for Treinterpretation by today’s filmmakers and film composers. -

Background Dates for Popular Music Studies

1 Background dates for Popular Music Studies Collected and prepared by Philip Tagg, Dave Harker and Matt Kelly -4000 to -1 c.4000 End of palaeolithic period in Mediterranean manism) and caste system. China: rational philoso- c.4000 Sumerians settle on site of Babylon phy of Chou dynasty gains over mysticism of earlier 3500-2800: King Menes the Fighter unites Upper and Shang (Yin) dynasty. Chinese textbook of maths Lower Egypt; 1st and 2nd dynasties and physics 3500-3000: Neolithic period in western Europe — Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (ends 1700 BC) — Iron and steel production in Indo-Caucasian culture — Harps, flutes, lyres, double clarinets played in Egypt — Greeks settle in Spain, Southern Italy, Sicily. First 3000-2500: Old Kingdom of Egypt (3rd to 6th dynasty), Greek iron utensils including Cheops (4th dynasty: 2700-2675 BC), — Pentatonic and heptatonic scales in Babylonian mu- whose pyramid conforms in layout and dimension to sic. Earliest recorded music - hymn on a tablet in astronomical measurements. Sphinx built. Egyp- Sumeria (cuneiform). Greece: devel of choral and tians invade Palestine. Bronze Age in Bohemia. Sys- dramtic music. Rome founded (Ab urbe condita - tematic astronomical observations in Egypt, 753 BC) Babylonia, India and China — Kung Tu-tzu (Confucius, b. -551) dies 3000-2000 ‘Sage Kings’ in China, then the Yao, Shun and — Sappho of Lesbos. Lao-tse (Chinese philosopher). Hsai (-2000 to -1760) dynasties Israel in Babylon. Massilia (Marseille) founded 3000-2500: Chinese court musician Ling-Lun cuts first c 600 Shih Ching (Book of Songs) compiles material from bamboo pipe. Pentatonic scale formalised (2500- Hsia and Shang dynasties (2205-1122 BC) 2000).