Joy Harjo Reads from 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fools Crow, James Welch

by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Office of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov Cover: #955-523, Putting up Tepee poles, Blackfeet Indians [no date]; Photograph courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, MT. by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Ofce of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov #X1937.01.03, Elk Head Kills a Buffalo Horse Stolen From the Whites, Graphite on paper, 1883-1885; digital image courtesy of the Montana Historical Society, Helena, MT. Anchor Text Welch, James. Fools Crow. New York: Viking/Penguin, 1986. Highly Recommended Teacher Companion Text Goebel, Bruce A. Reading Native American Literature: A Teacher’s Guide. National Council of Teachers of English, 2004. Fast Facts Genre Historical Fiction Suggested Grade Level Grades 9-12 Tribes Blackfeet (Pikuni), Crow Place North and South-central Montana territory Time 1869-1870 Overview Length of Time: To make full use of accompanying non-fiction texts and opportunities for activities that meet the Common Core Standards, Fools Crow is best taught as a four-to-five week English unit—and history if possible-- with Title I support for students who have difficulty reading. Teaching and Learning Objectives: Through reading Fools Crow and participating in this unit, students can develop lasting understandings such as these: a. -

MUSIC and MOVEMENT in PIXAR: the TSU's AS an ANALYTICAL RESOURCE

Revis ta de Comunicación Vivat Academia ISSN: 1575-2844 Septiembre 2016 Año XIX Nº 136 pp 82-94 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2016.136.82-94 INVESTIGACIÓN/RESEARCH Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 MUSIC AND MOVEMENT IN PIXAR: THE TSU’s AS AN ANALYTICAL RESOURCE Diego Calderón Garrido1: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Josep Gustems Carncier: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Jaume Duran Castells: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] ABSTRACT The music for the animation cinema is closely linked with the characters’ movement and the narrative action. This paper presents the Temporary Semiotic Units (TSU’s) proposed by Delalande, as a multimodal tool for the music analysis of the actions in cartoons, following the tradition of the Mickey Mousing. For this, a profile with the applicability of the nineteen TSU’s was applied to the fourteen Pixar movies produced between 1995-2013. The results allow us to state the convenience of the use of the TSU’s for the music comprehension in these films, especially in regard to the subject matter and the characterization of the characters and as a support to the visual narrative of this genre. KEY WORDS Animation cinema, Music – Pixar - Temporary Semiotic Units - Mickey Mousing - Audiovisual Narrative – Multimodality 1 Diego Calderón Garrido: Doctor in History of Art, titled superior in Modern Music and Jazz music teacher and sound in the degree of Audiovisual Communication at the University of Barcelona. -

Brave Waiting No

Sermon #1371 Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit 1 BRAVE WAITING NO. 1371 A SERMON DELIVERED ON LORDS-DAY MORNING, AUGUST 26, 1877, BY C. H. SPURGEON, AT THE METROPOLITAN TABERNACLE, NEWINGTON. “Wait on the Lord: be of good courage and He shall strengthen your heart: wait, I say, on the Lord.” Psalm 27:14. THE Christian’s life is no child’s play. All who have gone on pilgrimage to the celestial city have found a rough road, sloughs of despond and hills of difficulty, giants to fight and tempters to shun. Hence there are two perils to which Christians are exposed—the one is that under heavy pressure they should start away from the path which they ought to pursue—the other is lest they should grow fearful of failure and so become faint-hearted in their holy course. Both these dangers had evidently occurred to David and in the text he is led by the Holy Spirit to speak about them. “Do not,” he seems to say, “do not think that you are mistaken in keeping to the way of faith. Do not turn aside to crooked policy. Do not begin to trust in an arm of flesh, but wait upon the Lord.” And, as if this were a duty in which we are doubly apt to fail, he repeats the exhortation and makes it more emphatic the second time, “Wait, I say, on the Lord.” Hold on with your faith in God. Persevere in walking according to His will. Let nothing seduce you from your integrity—let it never be said of you, “You ran well, what did hinder you that you did not obey the truth?” And lest we should be faint in our minds, which was the second danger, the psalmist says, “Be of good courage, and He shall strengthen your heart.” There is really nothing to be depressed about. -

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

English 233: Tradition and Renewal in American Indian Literature

ENGLISH 233 Tradition and Renewal in American Indian Literature COURSE DESCRIPTION English 233 is an introduction to North American Indian verbal art. This course is designed to satisfy the General Education literary studies ("FSLT") requirement. FSLT courses are supposed to concentrate on textual interpretation; they are supposed to prompt you to analyze how meaning is (or, at least, may be) constructed by verbal artists and their audiences. Such courses are also supposed to give significant attention to how texts are created and received, to the historical and cultural contexts in which they are created and received, and to the relationship of texts to one another. In this course you will be doing all these things as you study both oral and written texts representative of emerging Native American literary tradition. You will be introduced to three interrelated kinds of "text": oral texts (in the form of videotapes of live traditional storytelling performances), ethnographic texts (in the form of transcriptions of the sorts of verbal artistry covered above), and "literary" texts (poetry and novels) written by Native Americans within the past 30 years that derive much of their authority from oral tradition. The primary focus of the course will be on analyzing the ways that meaning gets constructed in these oral and print texts. Additionally, in order to remain consistent with the objectives of the FSLT requirement, you will be expected to pay attention to some other matters that these particular texts raise and/or illustrate. These other concerns include (a) the shaping influence of various cultural and historical contexts in which representative Native American works are embedded; (b) the various literary techniques Native American writers use to carry storyteller-audience intersubjectivity over into print texts; and (c) the role that language plays as a generative, reality-inducing force in Native American cultural traditions. -

A Brave New World (PDF)

Dear Reader: In Spring 2005, as part of Cochise College’s 40th anniversary celebration, we published the first installment of Cochise College: A Brave Beginning by retired faculty member Jack Ziegler. Our reason for doing so was to capture for a new generation the founding of Cochise College and to acknowledge the contributions of those who established the College’s foundation of teaching and learning. A second, major watershed event in the life of the College was the establishment of the Sierra Vista Campus. Dr. Ziegler has once again conducted interviews and researched archived news paper accounts to create a history of the Sierra Vista Campus. As with the first edition of A Brave Beginning, what follows is intended to be informative and entertaining, capturing not only the recorded events but also the memories of those who were part of expanding Cochise College. Dr. Karen Nicodemus As the community of Sierra Vista celebrates its 50th anniversary, the College takes great pleas ure in sharing the establishment of the Cochise College Sierra Vista Campus. Most importantly, as we celebrate the success of our 2006 graduates, we affirm our commitment to providing accessible and affordable higher education throughout Cochise County. For those currently at the College, we look forward to building on the work of those who pio neered the Douglas and Sierra Vista campuses through the College’s emerging districtwide master facilities plan. We remain committed to being your “community” college – a place where teaching and learning is the highest priority and where we are creating opportunities and changing lives. Karen A. -

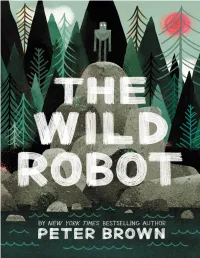

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

American Literature Association a Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25-28, 2017 Conference Director Olivia Carr Edenfield Georgia Southern University Program Draft as of April 25, 2017 This on-line draft of the program is designed to provide information to participants in our 28th conference and provide them with an opportunity to make corrections. Participants should check the description of their papers and panels to ensure that names and titles and other information are spelled appropriately. Organizers of Panels should verify that all sessions are listed properly, including business meetings that have been requested. It may be possible to add a business meeting. Also, organizers must make sure that they have contacted each of their panelists about registering for the conference. Please see below the important information regarding conference registration. Times of Panels: If there is a conflict in the program (i.e., someone is booked to appear in two places at the same time), please let me know immediately. The program indicates that a few slots for business meetings are still open, but it will be difficult to make other changes. You can presume that the day of your panel is now fixed in stone (and it will not change without the concurrence of every person on that panel) but it may be necessary to make minor changes in the time of a panel. Audio-Visual Equipment: The program makes note of all sessions that have requested AV. Please understand that it may be difficult or impossible to add any audio-visual requests at this point, but individuals may make such requests. -

Brave-Esampler-Margie.Pdf

Margie sets herself apart with a powerful and inspiring message, paired with her energetic, down-to-earth and disarming delivery. Margie’s insights helped me bolster my personal vision for a candid, collaborative and forward-leaning workplace. She provided practical advice on how to challenge ourselves and others to be more courageous, take more risks and find more success. Kathy Calvin, President and CEO, United Nations Foundation Nothing worthwhile is achieved living timidly and avoiding all risk. Brave will help you build the confidence to dare more boldly and live more bravely. Carolyn Cresswell, Company Founder and Managing Director, Carman’s Kitchen Fear and doubt are the two greatest enemies to success in business and life. Written for busy people on the go, this practical and encouraging book will guide you to achieve your greatest goals in work and life. Kate Carnell AO, CEO Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry Brave will help you grow your ‘courage muscles’ to achieve your biggest dreams and wildest ambitions. Read it often. Practise it daily. Emma Isaacs, CEO, Business Chicks If you have ever doubted your ability to achieve these wildly big goals, you don’t need to any longer! Brave needs to become your most valuable book as it will give you useful insight, tips and tricks to ensure you live your life fully! Paul McKeown, Head of Retail, The Body Shop Many people doubt themselves too much, and back themselves too little (particularly us women!). If you want to live more bravely, more boldly, and more fully, this book was written for you! It’s a game changer. -

Brave: the New Face of Princesses? by Aisling Breen May 2015

Brave: The New Face of Princesses? By Aisling Breen May 2015 Page | 1 This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfilment of the BA (Hons) Film degree at Dublin Business School. I confirm that all work included in this thesis is my own unless indicated otherwise. Aisling Breen May 2015 Supervisor: Barnaby Taylor Page | 2 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the help, contribution and support from the following people. I would not have been able to complete this without them: Barnaby Taylor Martin Breen Siobhan Breen Jason Muddiman Shane Hegarty The Disney Store Cast Members DBS Library Brenda Chapman Mark Andrews Thank you so much for your help and support. I appreciate every bit of it. Page | 3 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Page Introduction 5 The History of Animation 6 Chapter 2 Animation 11 Background of the Company 15 Chapter 3 Origins of Brave 19 Chapter 4 The Film 23 About Brave 27 Chapter 5 Responses to the Film 30 To Change or Not to Change 33 Chapter 6 Conclusion 36 References 43 Bibliography 45 Filmography 48 Page | 4 Chapter 1 Introduction The Pixar Animation Studios have been around for many years and in those years it has made some outstanding feature and short films. It has exchanged hands three times but has kept its flare and individuality. It is the company that has created some ground breaking technology that has changed how animation looks and is received today. It is the company that is making history for all the right reasons and makes childhood memorable and creating memories for the adults. -

MLS 589 Syllabus 2014

The Poetry of Earth How Science and Poetry Come Together from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass to Ernesto Cardenal’s Cosmic Canticle MLS 589 - Spring 2015 Steve Phelan (photo by Arthur Jones) Course Description: You’ve heard of science fiction. This course is all about science poetry. It will illustrate the few, but substantial poets, who in the tradition established by Lucretius two millennia ago, have created a new language and way of thinking, representing the human endeavor in the context of the whole earth and the cosmos, using our full and growing knowledge of the universe. Science poetry, then, often stands in contrast with the song of creation (as represented in the mythology of all cultures) and yet it also seems to work in consonance with it. While every poem creates its own place and hence implies its own creation account, Whitman’s masterpiece sets out to create a new Book of Genesis. Leaves of Grass sets the cosmic stage for all the poetry of the Americas and the democracy he imagined would engender the new world. So powerful was his song of creation that many poets to follow, in both North and South America, took heart and followed his grand score, creating ever new oracular voices of the indigenous spirit of the Americas. This course will explore the scientific, religious, and mythological basis of Whitman’s own creation and move forward to modern and contemporary poets of his kind: William Carlos Williams, our finest imagist poet, also wrote a long poem, Paterson, which uses collage techniques to create a modernist epic of place. -

Just As Nature Can Be Perceived Differently by Men and Women, Ethnicity Can Create Equally Distinctive Perceptions of the Natura

Anglo women's perceptions of the nature of the South- west have already received considerable attention of scholars.6 Although Chicanas and Native American women have perhaps been writing about the Southwest for years, only recently has Just as nature can be perceived differently by men and their literature been included in the genre of western and nature women, ethnicity can create equally distinctive perceptions of writing and as a consequence, there is not as much scholarly the natural world. As part of the United States "Frontier," the writing about them.? The predominant literary medium used by Southwest invites exceptional views of nature. In the Southwest Chicanas and Native American women is poetry, although not there is a blend of three distinct cultures: The Native Americans, limited to it. Pat Mora, Gloria Anzaldua, Beverly Silva, Luci who incorporate nature in to their daily lives; the Anglo Ameri- Tapahonso, Leslie Silko and Joy Harjo are all writers who have cans, who came to settle the new American frontier; and finally heen influenced by the Southwest. Some like Pat Mora and the Mestizos or Mexican Americans, who are a combination of (,Ioria Anzaldua were raised in the border area of Texas and 1 Indian and Spanish heritage. In The Desert is No Lady, edited experience these fronteraslborders as part of their daily lives. by Vera Norwood and Janice Monk, the authors conclude that: Beverly Silva, Leslie Silko and Luci Tapahonso, who are all city "women, alienated from their culture, feel lost and seek renewal dwellers, see the landscape through different eyes.s Interesting in the landscape; their search is not based on transcendence but in the work of Joy Harjo is the special attention given to feminist reciprocity, on personal vulnerability rather than heroic domi- thought.9 All these women have drawn their inspiration from the nance.