Doctoral Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

Gone with the Wind

Gone With The Wind by Margaret Mitchell STYLED BY LIMPIDSOFT Contents PART ONE4 CHAPTER I.................... 5 CHAPTER II.................... 42 CHAPTER III................... 77 CHAPTER IV................... 119 CHAPTER V.................... 144 CHAPTER VI................... 180 CHAPTER VII................... 248 PART TWO 266 CHAPTER VIII.................. 267 CHAPTER IX................... 305 CHAPTER X.................... 373 CHAPTER XI................... 397 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER XII................... 411 CHAPTER XIII.................. 448 CHAPTER XIV.................. 478 CHAPTER XV................... 501 CHAPTER XVI.................. 528 PART THREE 547 CHAPTER XVII.................. 548 CHAPTER XVIII................. 591 CHAPTER XIX.................. 621 CHAPTER XX................... 650 CHAPTER XXI.................. 667 CHAPTER XXII.................. 696 CHAPTER XXIII................. 709 CHAPTER XXIV................. 746 CHAPTER XXV.................. 802 CHAPTER XXVI................. 829 CHAPTER XXVII................. 871 CHAPTER XXVIII................ 895 CHAPTER XXIX................. 926 CHAPTER XXX.................. 952 3 CONTENTS PART FOUR 983 CHAPTER XXXI................. 984 CHAPTER XXXII................. 1017 CHAPTER XXXIII................ 1047 CHAPTER XXXIV................ 1076 CHAPTER XXXV................. 1117 CHAPTER XXXVI................ 1164 CHAPTER XXXVII................ 1226 CHAPTER XXXVIII............... 1258 CHAPTER XXXIX................ 1311 CHAPTER XL................... 1342 CHAPTER XLI.................. 1377 CHAPTER -

Wesley Historical Society Editor: E

Proceedings OFTHE Wesley Historical Society Editor: E. ALAN ROSE, B.A. Volume 49 October 1993 CHOSEN BY GOD: THE FEMALE TRAVELLING PREACHERS OF EARLY PRIMITIVE METHODISM The Wesley Historical Society Lecture 1993 t is just over a hundred years since the last Primitive Methodist female travelling preacher died. Elizabeth Bultitude (1809-1890) I had become a travelling preacher in 1832 and she superannuated after 30 years in 1862, dying in 1890. Of all the female itinerants the first, Sarah Kirkland (1794-1880), and the last, Elizabeth Bultitude, are the best known, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. Forty years ago Wesley Swift, wrote in the Proceedings about the female preach ers of Primitive Methodism: We have been able to identify more than forty women itinerants, but the full total must be considerably more.\ This was the starting point of my inquiry. First it is necessary to take a brief look at the whole question of women preaching. The Society of Friends, because they maintained both sexes equally received Inner Light, insisted that anyone who felt so called should be allowed to preach. So it was that many women within the Quaker movement were able to exercise their gifts of preaching without restriction. Many women undertook preaching tours both in this country and abroad, finding release from male-dominated society and religion and equal status with I Proceedings, xxix, p 79. 78 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WFSLEY HISTORICAL SocIETY men in preaching the word of God. For many years female preach ing was, on the whole, limited to the Quakers while the other denominations ignored it as being against Scripture, especially the Pauline injunction about women keeping silence in the church. -

Festiwal Chlebów Świata, 21-23. Marca 2014 Roku

FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA, 21-23. MARCA 2014 ROKU Stowarzyszenie Polskich Mediów, Warszawska Izba Turystyki wraz z Zespołem Szkół nr 11 im. Władysława Grabskiego w Warszawie realizuje projekt FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA 21 - 23 marca 2014 r. Celem tej inicjatywy jest promocja chleba, pokazania jego powszechności, ale i równocześnie różnorodności. Zaplanowaliśmy, że będzie się ona składała się z dwóch segmentów: pierwszy to prezentacja wypieków pieczywa według receptur kultywowanych w różnych częściach świata, drugi to ekspozycja producentów pieczywa oraz związanych z piekarnictwem produktów. Do udziału w żywej prezentacji chlebów świata zaprosiliśmy: Casa Artusi (Dom Ojca Kuchni Włoskiej) z prezentacją piady, producenci pity, macy oraz opłatka wigilijnego, Muzeum Żywego Piernika w Toruniu, Muzeum Rolnictwa w Ciechanowcu z wypiekiem chleba na zakwasie, przedstawiciele ambasad ze wszystkich kontynentów z pokazem własnej tradycji wypieku chleba. Dodatkowym atutem będzie prezentacja chleba astronautów wraz osobistym świadectwem Polskiego Kosmonauty Mirosława Hermaszewskiego. Nie zabraknie też pokazu rodzajów ziarna oraz mąki. Realizacją projektu będzie bezprecedensowa ekspozycja chlebów świata, pozwalająca poznać nie tylko dzieje chleba, ale też wszelkie jego odmiany występujące w różnych regionach świata. Taka prezentacja to podkreślenie uniwersalnego charakteru chleba jako pożywienia, który w znanej czy nieznanej nam dotychczas innej formie można znaleźć w każdym zakątku kuli ziemskiej zamieszkałym przez ludzi. Odkąd istnieje pismo, wzmiankowano na temat chleba, toteż, dodatkowo, jego kultowa i kulturowo – symboliczna wartość jest nie do przecenienia. Inauguracja FESTIWALU CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA planowana jest w piątek, w dniu 21 marca 2014 roku, pierwszym dniu wiosny a potrwa ona do niedzieli tj. do 23.03. 2014 r.. Uczniowie wówczas szukają pomysłów na nieodbywanie typowych zajęć lekcyjnych. My proponujemy bardzo celowe „vagari”- zapraszając uczniów wszystkich typów i poziomów szkoły z opiekunami do spotkania się na Festiwalu. -

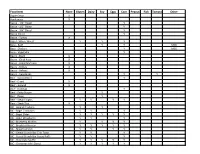

Quick Reference Allergy List

Food Item None Gluten Dairy Soy Eggs Corn Peanut Fish Tomato Other Apple Crisps X Applesauce X Bacon - 1/4" Diced Y Bacon - 1/2" Diced Y Bacon - 3/4" Diced Y Bacon Sliced Y Bacon - Turkey X Bagel - Whole Wheat Y Y Y Base - Beef Y Y MSG Base - Chicken Y MSG Base - Vegetable Y Beans - Black X Beans - Chick Peas X Beans - Great Northern X Beans - Kidney X Beans - Refried X Beans - Vegetarian Y Y Beef - Corned Beef Y Beef - Diced X Beef - Ground X Beef - Hot Dog Y Beef - Patty Burger Y Beef - Roast Y Beef - Steak Fingers Y Y Y Y Beef - Steak Tips X BIC - Animal Crackers Y Y BIC - Bagel Cinnamon Y Y Y BIC - Bagel Slider Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Bagel Strawberry Y Y Y BIC - Blueberry Muffins Y Y Y Y BIC - Breakfast Burrito Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Breakfast Stick Y Y Y Y BIC - Cereal Crunch Bar Cinn Toast Y Y Y BIC - Cereal Crunch Bar Cocoa Puffs Y Y Y BIC - Chocolate Muffin Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Cinnamon Mini Donut Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Early Risers Y Y Y Y BIC - French Toast Sticks Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Pancake in a Bag Y Y Y Y BIC - Pancake on a Stick Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Sausage Bites in a Bag Y Y Y Y BIC - Scooby Snacks Y Y Y BIC - Waffle Bites in a Bag Y Y Y Y Y Bread - Biscuit Y Y Y Bread - Dinner Roll Y Y Bread - English Muffin Y Y MC Y Bread - French Loaf Y Y Y Y Bread - Garlic Toast Y Y Y Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Dinner Roll Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Hamburger Bun Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Hot Dog Bun Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Sandwich Loaf Y Y Bread - Hamburger Bun Y Y Bread - Hoagie Large Y Y Bread - Hoagie Slider Y Y Bread - Hot Dog Bun Y Y Bread - Pita Round Y Y Y Bread - Sandwich/Loaf -

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 3 SUMMER 1991 The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and TERM wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included 1992 President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. 1992 Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 BACK ISSUES 1992 Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 1992 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 1992 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, OH 43068, (614) 861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 1992 Immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 generally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

Rustic Acres Farm SERVICE & PRICING GUIDE CONTENTS

Rustic Acres Farm SERVICE & PRICING GUIDE CONTENTS BE OUR GUEST /01 ABOUT JPC History & Philosophy /02 Amenities & Pricing /04 Ceremonies /05 Farm FAQs /06 CATERING So Much More Than Food /08 MENU Your Choice /11 Savory Family Style /13 Southern BBQ Family Style /17 Elegant Plated Sit Down /20 Chef Stations /25 Appetizer Enhancements /29 Sweet Endings /33 Bar Mixers & Beverage Services /38 CONNECT /40 / BE OUR GUEST BE OUR GUEST A rippling creek, rolling fields of pumpkins and sunflowers, grazing horses, expansive views and wind across the pond… This is Rustic Acres Farm. Founded in April 2011, Rustic Acres is located in the sprawling hills of rural Western Pennsylvania along Route 19 between the quaint village of Volant, and the bustling Grove City Outlet mall. From the majestic and iconic weeping willow, to sweeping pastoral views, a vast array of locations for a stunning wedding day ceremony and celebration exist within the acres of the farm. Managed by the award winning JPC EVENT GROUP, Rustic Acres Farm offers outdoor beauty, fine catering packages in a range of styles and tastes, inclusive equipment, and venue coordination that ensures a stress-free and memorable day for you and your guests. Come & experience life celebrated / 01 JPC HISTORY & PHILOSOPHY / ABOUT JPC HISTORY WE BRING YOUR VISION TO LIFE WITH EFFORTLESS ELEGANCE AND SEAMLESS PLANNING, IN SIGNATURE STYLE. Real people. real design. real food. / 02 ABOUT JPC Our history For over 23 years, we have followed our passion by creating memories for our clients that last a lifetime. We have always believed that quality is more impactful than quantity, and we strive to create events that engage all of your senses with a commitment to sustainability and quality local and seasonal ingredients often grown on our own JPC Willowbrook Farm. -

"I's Not So Wicked As I Use to Was:" the Interplay of Race and Dignity In

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons HON499 projects Honors Program Spring 2018 "I's Not So Wicked as I Use to Was:" The nI terplay of Race and Dignity in Nineteenth-Century American Drama and Blackface Minstrelsy Sam Volosky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects Part of the Acting Commons, African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Volosky, Sam, ""I's Not So Wicked as I Use to Was:" The nI terplay of Race and Dignity in Nineteenth-Century American Drama and Blackface Minstrelsy" (2018). HON499 projects. 16. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects/16 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in HON499 projects by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I’s Not So Wicked as I Use to Was:” The Interplay of Race and Dignity in Nineteenth-Century American Drama and Blackface Minstrelsy By Sam Volosky At the origin of theatrical performance, theatre was used by the ancient Greeks as an efficacious tool to enact social change within their communities. Playwrights used tragedy and comedy in order to sway their audiences so that they might vote in one direction or the other on matters such as war, government, and social structure. -

Rattlesnake Tales 127

Hamell and Fox Rattlesnake Tales 127 Rattlesnake Tales George Hamell and William A. Fox Archaeological evidence from the Northeast and from selected Mississippian sites is presented and combined with ethnographic, historic and linguistic data to investigate the symbolic significance of the rattlesnake to northeastern Native groups. The authors argue that the rattlesnake is, chief and foremost, the pre-eminent shaman with a (gourd) medicine rattle attached to his tail. A strong and pervasive association of serpents, including rattlesnakes, with lightning and rainfall is argued to have resulted in a drought-related ceremo- nial expression among Ontario Iroquoians from circa A.D. 1200 -1450. The Rattlesnake and Associates Personified (Crotalus admanteus) rattlesnake man-being held a special fascination for the Northern Iroquoians Few, if any of the other-than-human kinds of (Figure 2). people that populate the mythical realities of the This is unexpected because the historic range of North American Indians are held in greater the eastern diamondback rattlesnake did not esteem than the rattlesnake man-being,1 a grand- extend northward into the homeland of the father, and the proto-typical shaman and warrior Northern Iroquoians. However, by the later sev- (Hamell 1979:Figures 17, 19-21; 1998:258, enteenth century, the historic range of the 264-266, 270-271; cf. Klauber 1972, II:1116- Northern Iroquoians and the Iroquois proper 1219) (Figure 1). Real humans and the other- extended southward into the homeland of the than-human kinds of people around them con- eastern diamondback rattlesnake. By this time the stitute a social world, a three-dimensional net- Seneca and other Iroquois had also incorporated work of kinsmen, governed by the rule of reci- and assimilated into their identities individuals procity and with the intensity of the reciprocity and families from throughout the Great Lakes correlated with the social, geographical, and region and southward into Virginia and the sometimes mythical distance between them Carolinas. -

The House Nigger in Black American Literature Black American Literature

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI \ 4 / The House Nigger in Black Amer/ican Literature A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS in Literature by Margeretta wa Gacheru NOVEMBER, 1985 This Thesis has been submitted for examination .. with our approval as supervisors: - • ,ees> r . Signed: { ^ \ r' c°v Dr Kimani Gecau5 VSS*vN S igned: Dr. Henry Indangasi UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY This dissertation is my original work and has not been submitted for a degree in any other University. This dissertation has been submitted for examination with my approval as University supervisors: Signed: ■f-* DR. KIMANI GECAU Signed: DR. HENRY INDANGASI LIST O F CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements ... (iv) Abstract (v) 1 Introduction 2. The House Nigger in Black American Literature Black American Literature ... ... 18 3. Ralph Ellison: The Case of a Good House Nigger 77 4. Invisible Man: A House Nigger Masterpiece. 102 5. Conclusion ... 139 6. Footnotes 7. Bibliography ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Kimani Gecau for his consistent concern for the progress of this dissertation, for all the hours of provocative, progressive and constructive discussion, and for his patience as well as his alacrity so often displayed while this work was still in embryo (and when at times it looked like it would be a still birth). I am also most appreciative of the efforts of Dean Micere Mugo whose combined strengths of administrative aptitude and academic excellence have been something of a shining light to me in the long night of this thesis' preparation. -

Wesley Historical Society Editor: E

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: E. ALAN ROSE, B.A. Volume 56 February 2008 CHARLES WESLEY, 'WARTS AND ALL': The Evidence of the Prose Works The Wesley Historical Society Lecture 2007 Introduction ccording to his more famous brother John, Charles Wesley was a man of many talents of which the least was his ability to write A poetry.! This is a view with which few perhaps would today agree, for the writing of poetry, more specifically hymns, is the one thing above all others for which Charles Wesley has been remembered. Anecdotally I am sure that we all recognise that this is the case; and indeed if one were to look Charles up in more or less anyone of the many general biographical dictionaries that include an entry on him one will find it repeated often enough: Charles is portrayed as a poet and a hymn writer; while comparatively little, if any, attention is paid to other aspects of his work. On a more scholarly level too one can find it. Obviously there are exceptions, but in general historians of Methodism in particular and eighteenth-century Church history more widely have painted a picture of Charles that is all too monochrome and Charles' role as the 'Sweet Singer of Methodism' is as unquestioned as his broader significance is undeveloped. The reasons for this lack of full attention being paid to Charles are several and it is not (contrary to what is usually said) simply a matter of Charles being in his much more famous brother's shadow; a lesser light, as it were, belng outshone by a greater one.