Introduction to Instalment 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josquin Des Prez: Master of the Notes

James John Artistic Director P RESENTS Josquin des Prez: Master of the Notes Friday, March 4, 2016, 8 pm Sunday, March 6, 2016, 3pm St. Paul’s Episcopal Church St. Ignatius of Antioch 199 Carroll Street, Brooklyn 87th Street & West End Avenue, Manhattan THE PROGRAM CERDDORION Sopranos Altos Tenors Basses Gaude Virgo Mater Christi Anna Harmon Jamie Carrillo Ralph Bonheim Peter Cobb From “Missa de ‘Beata Virgine’” Erin Lanigan Judith Cobb Stephen Bonime James Crowell Kyrie Jennifer Oates Clare Detko Frank Kamai Jonathan Miller Gloria Jeanette Rodriguez Linnea Johnson Michael Klitsch Michael J. Plant Ellen Schorr Cathy Markoff Christopher Ryan Dean Rainey Praeter Rerum Seriem Myrna Nachman Richard Tucker Tom Reingold From “Missa ‘Pange Lingua’” Ron Scheff Credo Larry Sutter Intermission Ave Maria From “Missa ‘Hercules Dux Ferrarie’” BOARD OF DIRECTORS Sanctus President Ellen Schorr Treasurer Peter Cobb Secretary Jeanette Rodriguez Inviolata Directors Jamie Carrillo Dean Rainey From “Missa Sexti toni L’homme armé’” Michael Klitsch Tom Reingold Agnus Dei III Comment peut avoir joye The members of Cerddorion are grateful to James Kennerley and the Church of Saint Ignatius of Petite Camusette Antioch for providing rehearsal and performance space for this season. Jennifer Oates, soprano; Jamie Carillo, alto; Thanks to Vince Peterson and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church for providing a performance space Chris Ryan, Ralph Bonheim, tenors; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses for this season. Thanks to Cathy Markoff for her publicity efforts. Mille regretz Allégez moy Jennifer Oates, Jeanette Rodriguez, sopranos; Jamie Carillo, alto; PROGRAM CREDITS: Ralph Bonheim, tenor; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses Myrna Nachman wrote the program notes. -

A Conversation with Josquin

A Conversation and a skip later I found myself face to face with a rural to spot, sometimes extremely difficult, in various keys, once more. policemen, who looked perfectly ridiculous in a red with added rests…but the whole thing is always there, “Maurice, this is very good, you’ve done the work of an with Josquin and gold uniform and towering kepi. like in the superius of the Gloria and the “complaint honest artisan. You’ve written in the Franco-Flemish “Your music, please!” machines” in the bass of the Agnus 2.” style, and done the best you could with what you Those bright and beady eyes…why, yes, they were Josquin bent over the score, more and more interested: have.” In the church of Sainte Croix Vallée-Française, I was Josquin’s! He was actually there, and easily recognizable “This notation is wonderful, with the four voices one He winked and slipped away. about to give the starting pitch for the eleven singers in in his high green stockings. And he was obviously very above the other. In my day, we had to count the beats I opened my eyes. My scores were before me, and there the Métamorphoses and Biscantor! ensembles. cross. and really pay attention. When it’s printed like this, were the singers, waiting patiently. The pitch pipe I closed my eyes for a second… “What’s this Chascun me crie ...même Hercule! mass? you can take it easy…even have a snooze from time sounded an “A” and the first notes of the Kyrie from …and when I opened them again…my binder was I never wrote such a thing!” to time!” Hercules could finally plunge me into a marvelous empty! My music had disappeared! My tools, my “Calm down, Josquin…You and a lot of other people And then with great enthusiasm: fountain of youth. -

The University of Oklahoma Graduate College A

THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A CONDUCTOR’S RESOURCE GUIDE TO THE OFFICE OF COMPLINE A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By D. JASON BISHOP Norman, Oklahoma 2006 UMI Number: 3239542 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3239542 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 A CONDUCTOR’S RESOURCE GUIDE TO THE OFFICE OF COMPLINE A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY Dr. Dennis Shrock, Major Professor Dr. Irvin Wagner, Chair Dr. Sanna Pederson, Co-Chair Dr. Roland Barrett Dr. Steven Curtis Dr. Marilyn Ogilvie ' Copyright by D. JASON BISHOP 2006 All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction Purpose of the Study 1 Need for the Study 2 Survey of Related Literature 3 Scope & Limitations of the Study, -

Repertories. Tinctoris, Gaffurio and the Neapolitan Context*

GIANLUCA D'AGOSTINO READING THEORISTS FOR RECOVERING 'GHOST' REPERTORIES. TINCTORIS, GAFFURIO AND THE NEAPOLITAN CONTEXT* In 1478 the Italian theorist Franchino Gaffurio moved to Naples. The two-year stay at the local Aragonese court was essential for his edu cation for he had the opportunity to meet Johannes Tinctoris, who by that time had completed many of his known treatises. It has long been recognized that Tinctoris deeply influenced Gaffurio's thoughts on sever al controversial topics, such as proportions and mensuration signs, and the mensura! treatment of counterpoint.' Echoes, and even literal quotations, of Tinctoris' statements and crit icisms resound in Gaffurio's famous Practica musicae in four books (Mi lan, 1496), and- even more strongly- in his two earlier versions of sin gle books of the Practica (book 2: Musices practicabilis libellus; book 4: Tractatus practicabilium proportionum), compiled as independent treatis es soon after his departure from Naples, in the early 1480s. Many years * This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper read at the Med-Ren Music Conference held in Glagow, July 2004. It is ideally linked to two previous articles on similar topics already appeared in these «Studi Musicali» (:XXVIII-1999; X:XX-2001). Wormest thanks are due to Bonnie J. Blackbum, Margaret Bent and David Fallows, for their many help ful suggestions and improvements. 1 On this subject see: F. ALBERTO GALLO, Le traduzioni dal Greco per Franchino Gaffu rio, «Acta Musicologica», XXXV, 1963, pp. 172-174; ID., Citazioni da un trattato di Du/ay, «Collectanea Historiae Musicae», N, 1966, pp. 149-152; ID., lntrod. -

Harpsichord - Organ - Accordion

UT ORPHEUS EDIZIONI Keyboard Music Piano - Harpsichord - Organ - Accordion Complete Catalogue December 2020 www.utorpheus.com CONTENTS Piano Chamber Music ...............................16 Methods, Studies & Easy Pieces ������������� 3 Concertos .....................................17 Piano solo ...................................... 3 Piano 4 Hands .................................. 9 Organ Piano 6 or more Hands ....................... 9 Methods, Studies & Easy Pieces ������������18 2 Pianos ......................................... 9 Organ solo .....................................18 Concertos .....................................10 Organ 4 Hands ................................22 Books ...........................................10 2 Organs .......................................22 Organ and Violin �����������������������������23 Harpsichord Organ and Flute ..............................23 Methods, Studies & Easy Pieces ������������11 Organ and Voice ..............................23 Harpsichord solo .............................11 Chamber Music ...............................23 Harpsichord 4 Hands .........................15 Concertos .....................................23 2 Harpsichords ................................15 Harmonium....................................24 Harpsichord and Violin ......................16 Harpsichord and Flute .......................16 Accordion Harpsichord and Guitar .....................16 Accordion solo ................................24 Harpsichord and Voice ......................16 Accordion and Orchestra....................24 -

Masterworks from the Flemish Renaissance Saturday, March 14, 2009 PROGRAM

QClevelanduire Peter Bennett, director Masterworks from the Flemish Renaissance Saturday, March 14, 2009 PROGRAM Johannes Ockeghem (ca.1410–1497) Intemerata Dei mater Henricus Isaac (ca.1450–1517) Quis dabit capiti meo aquam Rogamus te (La mi la sol) Josquin Desprez (ca.1450-55–1521) Ave Maria Jean Mouton (ca.1459–1522) Per Lignum Nesciens mater Adrian Willæert (ca.1490–1562) Verbum bonum — Ave, solem genuisti Aures ad nostras Jacques Arcadelt (ca.1507–1568) Pater noster — intermission — Nicolas Gombert (ca.1495–ca.1560) Musæ Iovis Magnificat tertii et octavi toni Jacobus Clemens non Papa (ca.1510–ca.1555) Ego flos campi Sancta Maria Cipriano de Rore (1515/16–1565) Descendi in hortum meum Roland de Lassus (1532–1594) Musica, Dei donum optimi Surrexit Dominus vere Philippe de Monte (1521–1603) O suavitas et dulcedo Upcoming Quire Cleveland Performances Tuesday–Sunday, May 5–10, 2009 CityMusic Cleveland, James Gaffigan, conductor “Heaven & Earth: Schubert & Mozart” — Schubert’s Stabat Mater and Mass in G Major Six concerts in Northeast Ohio. Free admission. Visit www.citymusiccleveland.org for details PROGRAM NOTES All of the composers represented on this concert were Franco-Flemish, by which music historians mean that they were born in the region primarily represented by Belgium today, but were primarily francophone. With the exception of Clemens non Papa, who seems to have stayed around the Low Countries throughout his life, they were all international “superstars,” traveling and working all over Europe, and especially in Italy—in many ways the seat of wealth and culture during the Renaissance. Why were Franco-Flemish composers so successful? It certainly started with the strength of the maîtrises, the choir schools, who were training the most sought-after singers in Europe throughout this period and, in fact, dating back into the fourteenth century. -

1933U6 Nannette Reese Hanslowe, B

79 Maf ?SOO( rn A STUDY OF THE ORIGINS AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE MAJOR SEVENTH CHORD THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ivUSIC By 1933u6 Nannette Reese Hanslowe, B. M. Denton, Texas August, 1951 1933'J$ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page""k, LIST OF TABLES . * . * * . * * " a iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . I v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . , . .a 1 II. THE USE OF TIE I4AJOR SEVENTh CHORD IN THE PHEYGIAN CADENCE . ., ,. 7 III. THE USE OF TEE MAJOR SEVENTH CHORD IN AUTHENTIC CADENCES . 40 IV. THE USE OF THE MAJOR SEVENTH CHORD IN SEQUENCES AND SUSPENSION CHAINS . .. 60 V. THE IRREGULAR USES OF THE MAJOR SEVENTH CHORD * * - - - * - .1 -*.*-0-#-& . & . 1 87 VI. CONCLUSIONS * -.- a a9 a a a9 0 a9 a0 a9 a9 . 107 a 9- 9 0. 9 APPENDIX * 0 - 9 9 9 - , - a a 9 9 0 0 112 BIBLIOGRAPEY *.- * - . .*- . - 9 9 9* . 0 - . 0 . 113 III LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1. Tabulation of the Examples of Irregular Uses of the Major Seventh Chord Mentioned in ChapterV . -a-0-0-0-0**...* - . .*112 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Voice Leading of the hrygian Cadence . 8 2. Johann Sebastian Bach, "Erbarm' Dich Mein, 0 Herre Gott" . * @0 8 3. Georg Frederick Handel, "Sonata No. 4" . 4. Arcangelo Corelli, "Sonata X" . 10 5. Glausulse for "Hec Dies" . - - - . 12 6. Phrygian Cadence circa 1400 . 13 7. Conrad Paumann, Fundamentum organsandi 13 8. Johannes Martini, "La LMartinella" . 14 9. Jakob Hobrecht, "Pleni und Agnus Dei II". -

Jan Pıeterszoon Sweelınck´In Toccata´Larının Klasik Gitar Ile Icra

Hacettepe Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Enstitüsü Piyano Anasanat Dalı JAN PIETERSZOON SWEELINCK´İN TOCCATA´LARININ KLASİK GİTAR İLE İCRA EDİLEBİLMESİ ÜZERİNE BİR ARAŞTIRMA Kerim Özcan DAL N11230441 Yüksek Lisans Tezi Ankara, 2014 i JAN PIETERSZOON SWEELINCK´İN TOCCATA´LARININ KLASİK GİTAR İLE İCRA EDİLEBİLMESİ ÜZERİNE BİR ARAŞTIRMA Kerim Özcan DAL N11230441 Hacettepe Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Enstitüsü Piyano Anasanat Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi Ankara, 2014 iv ÖZET DAL, Kerim Özcan. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck’in Toccataları’nın Klasik Gitar ile İcra Edilebilmesine Yönelik Bir Araştırma, Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara, 2014. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck’in Toccataları’nın Klasik Gitar ile İcra Edilebilmesi bu araştırmanın temelini oluşturmaktadır. “Giriş” kısmında bulgulara yön verecek şekilde bazı tanımlar yapılacak, çeşitli kavramlar açıklığa kavuşturulacak ve problem durumuna değinilecektir. “Yöntem” kısmında araştırmada hangi yöntemlerle kaynak tarandığı ve bulgulara ulaşıldığı açıklanacaktır. Ardından “Bulgular ve Yorumlar” kısmında araştırmanın problem durumuna yönelik bulgular elde edilecek ve bunlar yorumlanacaktır. Son olarak araştırmanın “Sonuç ve Öneriler” kısmında, elde edilen bulgular ışığında ulaşılan sonuçlara yer verilerek öneriler getirilecektir. Anahtar Sözcükler Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Toccata, İki gitar, Klasik gitar v ABSTRACT DAL, Kerim Özcan. A Research About Performing Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck’s Toccatas on Classcical Guitar, Master´s Thesis, Ankara, 2014. The aim of this work is to perform toccatas written for organ by the Renaissance period composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. In the first part, there will be definitions and well-substantiated explanations to cast more light on the findings. The second part will cover the methods of scanning sources to reach findings of the research. The third part will include the findings with their interpretation. Finally, there will be results about the findings obtained, along with suggestions that made in the conclusion of this research. -

A Selective List of Masters' Theses in Musicology

2 A SELECTIVE LIST OF MASTERS’ THESES IN MUSICOLOGY Compiled for The American Musicological Society by Dominique-René de Lerma Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana Denia Press 1970 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 The bibliography 6 Index of proper names 32 Index of topics 36 Index of participating institutions 40 4 INTRODUCTION This bibliography was developed on the request of Professor William S. Newman, president of the American Musicological Society, who shares with his colleagues an awareness that masters’ theses in musicology have not previously been subjected to bibliographic control. Nominations for inclusion were requested of fifty—five American universities by mail in June of 1969. This was supplemented by announcements in the Newsletter of the American Musicological Society (Chapel Hill, February 1970, p.3) and in the Music Library Association’s Notes (Ann Arbor, March 1970, v.26, no.3, p.497—8), and by additional correspondence with the universities in February of 1970. Nominations which were received by May 7, 1970 have been included. The participating institutions were requested to submit bibliographic data on those theses which were regarded as outstanding. Although no limits regarding the number each school might submit were firmly established, it was recommended that between five and ten titles might satisfy the needs. A total of 257 titles were submitted by 36 schools. A few institutions offered an additional list of all theses accepted in musicology as an expression of interest in a comprehensive bibliography. Two schools included citation of papers accepted for the D.M.A. degree, noting that such work is not registered in any existing source. -

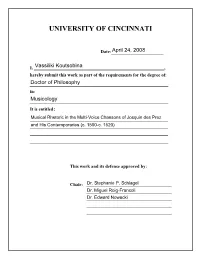

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Musical Rhetoric in the Multi-Voice Chansons of Josquin des Prez and His Contemporaries (c. 1500-c. 1520) A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Division of Composition, Musicology and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music By VASSILIKI KOUTSOBINA B.S., Chemistry University of Athens, Greece, April 1989 M.M., Music History and Literature The Hartt School, University of Hartford, Connecticut, May 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Stephanie P. Schlagel 2008 ABSTRACT The first quarter of the sixteenth century witnessed tightening connections between rhetoric, poetry, and music. In theoretical writings, composers of this period are evaluated according to their ability to reflect successfully the emotions and meaning of the text set in musical terms. The same period also witnessed the rise of the five- and six-voice chanson, whose most important exponents are Josquin des Prez, Pierre de La Rue, and Jean Mouton. The new expanded textures posed several compositional challenges but also offered greater opportunities for text expression. Rhetorical analysis is particularly suitable for this repertory as it is justified by the composers’ contacts with humanistic ideals and the newer text-expressive approach. Especially Josquin’s exposure to humanism must have been extensive during his long-lasting residence in Italy, before returning to Northern France, where he most likely composed his multi- voice chansons. -

M2020104 Ric 430 LA FLEUR DE BIAULTÉ 21X28 WEB.Indd

LYRICS P. 22 16 11 6 P. LYRICS P. DEUTSCH 4 FRANÇAIS P. P. ENGLISH P. TRACKLIST MENU — MENU EN FR DE LYRICS This recording has been made with the support of the Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (Direction générale de la Culture, Service de la Musique) 2 Recording: Leymen (F), église Saint-Léger, September 2020 Artistic direction & recording: Jérôme Lejeune Illustration: Lorenzo Costa (1460-1535), The Reign of Comus,1511 (detail) Paris, Musée du Louvre © Hervé Champollion / akg-images Photos (p. 5 & 36 ) © Elam Rotem JOHANNES MARTINI LYRICS ca 14301497 DE DE FR FR LA FLEUR DE BIAULTÉ — LE MIROIR DE MUSIQUE MENU EN Sabine Lutzenberger & Tessa Roos: mezzo-sopranos 3 David Munderloh & Jacob Lawrence: tenors Matthieu Le Levreur: baritone Tim Scott Whiteley: bass Claire Piganiol: harp & organetto Silke Schulze: shawm & pommer Elizabeth Rumsey: viola d'arco & renaissance viola da gamba Marc Lewon: lute & viola d'arco Henry van Engen: trombone Baptiste Romain: vielle, renaissance violin, rebec, bagpipes & direction www.lemiroirdemusique.com 1. O beate Sebastiane 5'38 2. La Martinella 2'12 3. La Martinelle pittzulo 1'10 4. Letatus sum 3'00 5. Biaulx parle toujours 1'24 6. La fleur de biaulté 1'39 7. Quare fremuerunt gentes 4'47 8. Magnificat tertii toni 9'39 9. Helas comment aves 2'53 10. Que je fasoye 0'46 11. Fortuna desperata 1'19 12. Fortuna disperata – Anonymous (Bologna Q18) 1'20 13. Fortuna d'un gran tempo 3'25 4 14. Scoen kint 4'16 15. Sans riens du mal 5'14 16. J’espoir mieulx 4'13 17. -

Score and Parts / Richard Ayres. - Mainz : Schott ; [Etc.] : [S.N.], Cop

No. 38 : (three small pieces for string quartet) : (2003) : score and parts / Richard Ayres. - Mainz : Schott ; [etc.] : [s.n.], cop. 2011. - 40 p. ; 31 cm + 4 partijen. - (Edition Schott ; 13252) (Zeitgenösschische Musik für Streichquartett = Contemporary music for string quartet = Musique contemporaine pour quatuor à cordes) Tijdsduur: ca. 12 min. Plaatscode: Ks Ayre 1 Sonata : per pianoforte solo : (2001) / Luciana Berio. - Wien : Universal, cop. 2001. - 14 p. ; 31 cm Bron van beschrijving: omslag Tijdsduur: 26 min. Plaatscode: P Beri 6 Concertino : pour saxophone alto et orchestre / E. Bozza ; saxophone et piano. - Paris : Leduc, cop. 1939. - 26 p. : portr. ; 31 cm + 1 partij Jaar van compositie: 1938 Met biografie in het Frans, Duits, Engels en Spaans Delen: 1. Fantasque et léger ; 2. Andantino sostenuto ; 3. Allegro vivo Plaatscode: Sax Bozz 8 Músíca ibéríca : Spanish guitar music of the 19th century = Spanische Gitarremusik des 19. Jh. = Músíca Española para guitarra de siglo XIX / edited by = herausgegeben von = editado por Rafael Catalá. - Wien : Doblinger ; [etc.] : [s.n.], cop. 20..-20.. - ; 30 cm Plaatscode: G Músí 1 Polonaise brillante Opus 3 und Duo concertant : für Klavier und Violoncello = Polonaise brillante op. 3 and Duo concertant : for piano and violoncello / Frédéric Chopin ; herausgegeben von = edited by Ernst- Günter Heinemann ; Fingersatz der Klavierstimme von = fingering of piano part by Andreas Groethuysen ; mit zusätzlicher bezeichneter Violoncellostimme von = with supplementary violoncello part marked by Claus Kanngiesser. - Urtext. - München : Henle, cop. 2006. - VIII, 48 p. ; 31 cm + 1 partij Bevat: Introduktion und Polonaise, op.003 en Grand duo concertant, KK.IIb.1 Met voorwoord in Duits, Engels en Frans van Ernst-Günter Heinemann Kritisch commentaar in Duits en Engels van Ernst-Günter Heinemann Samenvatting: De polonaise brillante schreef Chopin voor een van de dochters van de Poolse Prins Radziwill, Wanda, die het stuk met haar cello spelende vader kon oefenen.