NSIAD-88-77 Army Disposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan Crew Supervision

Qualification Handbook DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan crew supervision QN: 603/3232/3 The Qualification Overall Objective for the Qualifications This handbook relates to the following qualification: DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan crew supervision Pre-entry Requirements Learners are required to have completed the Class ME (Armd) Class 0-2 course, must be fully qualified AFV crewman and hold full category H driving licence Unit Content and Rules of Combination This qualification is made up of a total of 6 mandatory units and no optional units. To be awarded this qualification the candidate must achieve a total of 13 credits as shown in the table below. Unit Unit of assessment Level GLH TQT Credit number value L/617/0309 Supervise Titan Operation and 3 25 30 3 associated Equipment L/617/0312 Supervise Titan Crew 3 16 19 2 R/617/0313 Supervise Trojan Operation and 3 26 30 3 associated Equipment D/617/0315 Supervise Trojan Crew 3 16 19 2 H/617/0316 Supervise Trojan and Titan AFV 3 10 19 2 maintenance tasks K/617/0317 Carry out emergency procedures and 3 7 11 1 communication for Trojan and Titan AFV Totals 100 128 13 Age Restriction This qualification is available to learners aged 18 years and over. Opportunities for Progression This qualification creates a number of opportunities for progression through career development and promotion. Exemption No exemptions have been identified. 2 Credit Transfer Credits from identical RQF units that have already been achieved by the learner may be transferred. -

K0-41Io ARMO'r on OKINAWA

I k0-41io ARMO'R ON OKINAWA A RESEARCH REPORT PREPARED BY COL2JIaTTEE 1., OFFICERS ADV~ANCED COURSE THE ARIJJDD SCHOOL 1948-1949 MAJOR J.1L. BALTHIS ML.AJOR P. Go. SHOMffONEK MAJOR R. B. CRAYTON4 M.,AJOR L. H. JOHNSO CAPTAIN T. Q. DONALDSON CAr~PT'l4 D. L. JOHNvSON CAPTAIN W. Jo HYDE 1st LIEUTENANTd.To. WOODSON, JR. FORT K§v"OX, KH&!TUCKY MA1Y 1949 e A t- L - A ARMOR OKNA WA "-4j ~i4L f -' lip .V1 (1', July 1886-i8 June 1)/45) bon3 ul 1I6 ie&P Iunf ordile Ky., son of the cel-ebrated Confederate general, Simon Bolivar Buckner. The onerBuckner ch,,ose a mii ta,,r career, as had his father. 1 fter attending the iirgnia ilitry Istiute, he entered th-e U-,nited States Ml itary AIcadem, from.r which. h-e graduated in 1903. He was instruc- w--r in -,ilit-ry tactics at WIest Point from 1919 to 1923, and- COM- 2andant of cadets from 193)'2 to 1936 . Dudring World .Jar I, h-e comn- -unaded aviat'1ion training brigades. -:ieral Buckner was given, comuand of th e 1 1as a r6efenie force in dyan 940plyeda pomientrole in t1,e recapture of the -euionsin 1942-43. He was awarded the D.S.M,. in Oct. '1943, ' 1 Promoted t te4te iplDorary rank- o.L eter Generl. 1-was - Ler sent to t-he Ccntral PacifcComn, hr ho gai-ned cormmand the, new,, U.S. TNT1H A2LY. T1his a ,under his cormmand, invaded JNL~kI, on 1 A'pril 11945,95in1 three days bef'ore the lose of the Okinawan camnaign, General Buckner was fatally wounded r by a piece of coral, ahrcwn by the expl1osion of an c-eyartill cry S'4 PREFACE The capture of OKINAWIA was essentially en infantry effort with the result tha-).t armor wtuas at all times in support of infantry units. -

Part II Session 3 “Technology to Seize an Enemy-Held Shore”

Part II Session 3 “Technology to Seize an Enemy-held Shore” 1 Opposed Allied Amphibious Operations Prior to Normandy-Many Painful Lessons • UK-Norway, April 1940 • UK-Dakar, September 1940 • UK-Madagascar, May 1942 • UK/Canadian-Dieppe raid on the French coast, August 1942 • US/UK-Torch-Casablanca, Oran and Algiers, Nov 1942 • US/UK- Sicily/Italy – Sicily (Husky), Salerno (Avalanche), Anzio (Shingle), July –September 1943 2 “How to seize an enemy-held shore” • Examine from that past, then plan, plan, review the plan and exercise what you can of the plan. • Make sure that some one was in-charge of each action and was drilled in what to do. • What are the Germans doing and what would be a German response? Plan for that response. • Special training, new weapons, what do you need to clear the beach, how do you protect the landing forces, where is the unified command and control? 3 “How to seize an enemy-held shore” • While some of this sessions applies in the Pacific, the context here is a build up for the Normandy invasion: - One million troops and a 100,000 vehicles and everything needed to kept functioning. - The Normandy invasion was on the shore of a continent. • The Pacific War was a series of island invasions or jungle enclaves in New Guinea. No opposing armor, limited air cover or the probably of massed reserves. • Only the Philippine invasion and the possible invasion of the Japanese home Islands in November 1945 had the scope of Normandy. 4 What a Successful Amphibious Landing Requires-1 • Off-shore Command ships containing cooperative inter- service and inter-Allied staffs functioning below the Senior Chiefs level. -

Construction Sector Technical Education and Skills

TRAINING REGULATIONS Heavy Equipment Operation (Bulldozer) NC II CONSTRUCTION SECTOR TECHNICAL EDUCATION AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT AUTHOR ITY East Service Road, South Superhighway, Taguig City, Metro Manila BULLDOZER TR HEAVY - EQUIPMENT OPERATION (Bulldozer) Promulgated July 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONSTRUCTION - HEAVY EQUIPMENT SUB - SECTOR HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION (BULLDOZER) NC II SECTION 1 HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION QUALIFICATION SECTION 2 COMPETENCY STANDARDS SECTION 3 TRAINING STANDARDS 3.1 Curriculum Design 3. 2 Training Delivery 3.3 Trainee Entry Requirements 3.4 List of Tools, Equipment and Materials 3.5 Training Facilities 3.6 Trainers' Qualifications SECTION 4 ASSESSMENT AND CERTIFICATION ARRANGEMENT COMPETENCY MAP DEFINITION OF TERMS ACKNOWLEDGEMEN TS TR HEAVY - EQUIPMENT OPERATION (Bulldozer) Promulgated July 2007 TRAINING REGULATIONS FOR HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION - BULLDOZER SECTION 1 HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION - BULLDOZER The HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION (BULLDOZER) NC II qualification consists of competencies that workers must achieve to enable them to perform tasks such as excavating, dozing, ripping, winching, and clearing of earth materials in construction sites or other locations. This qualification is packaged from the competency map of Construction - Heavy Equipment sub - sector as shown in Annex A. The units of competency comprising this qualification include the following: CODE NO. BASIC COMPETENCIES Units of Competency 500311105 Participate in workplace communication 500311106 Work in a team environment 500311107 Practice career professionalism 500311108 Practice occupational health and safety procedures CODE NO. COMMON COMPETENCIES Units of Competency CON931201 Prepare construction materials and tools CON311201 Observe procedures, specifications and manuals of inst ruction CON311202 Interpret technical drawings and plans CON311203 Perform mensurations and calculations CON311204 Maintain tools and equipment CODE NO. -

Khumani Iron Ore Mine

Khumani Iron Ore Mine Final Rehabilitation Plan for 2018/2019 Report Purpose Providing the client and Regulatory Authority with an understanding of the Final Closure Plan for the mine. Report Status FINAL Report Reference EnviroGistics Ref.: 21814 Departmental Ref.: NC 30/5/1/2/3/2/1/070EM and amendments 2007, 2011, 2012 Report Authors Tanja Bekker (EnviroGistics) MSc. Environmental Management Certified EAPSA; SACNASP Reg. 400198/09 Ferdi Pieterse (Globesight) BSc. (Hons) Environmental Management 4 June 2018 PO Box 22014 | Helderkruin | 1733 [email protected] 082 412 1799 086 551 5233 ENVIROGISTICS (PTY) LTD 6/4/18 KHUMANI IRON ORE MINE 2018 FINAL REHABILITATION PLAN Departmental Ref: NC 30/5/1/2/3/2/1/070EM and amendments 2007, 2011, 2012, 2016 Project Ref: 21814 Version: FINAL Author Tanja Bekker is registered as a Professional Natural Scientist in the field of Environmental Science with the South African Council for Natural Scientific Professions (SACNASP) and is also a Certified Environmental Assessment Practitioner (EAP) with the Interim Certification Body of the Environmental Assessment Practitioners of South Africa (EAPSA), a legal requirement stipulated by the National Environmental Management Act, 1998. She is further certified as an ISO 14001 Lead Auditor. Her qualifications include BSc. Earth Sciences (Geology and Geography), BSc. Hons. Geography, and MSc. Environmental Management. In addition to her tertiary qualifications, she obtained a Certificate in Project Management, and completed the Management Advancement Programme at Wits Business School. With more than 14 years' experience in environmental management and the consulting industry, she follows a methodical and practical approach in attending to environmental problems and identifying environmental solutions throughout the planning, initiation, operation and decommissioning or closure of projects. -

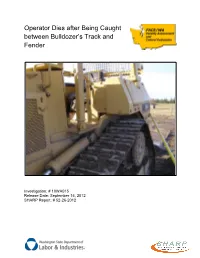

Operator Dies After Being Caught Between Bulldozer's Track and Fender

Operator Dies after Being Caught between Bulldozer’s Track and Fender Investigation: # 10WA015 Release Date: September 14, 2012 SHARP Report: # 52-26-2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE SUMMARY 3 RECOMMENDATIONS 3 INTRODUCTION 4 Employer 4 Employer Safety Program and Training 4 Victim 5 Equipment 5 INVESTIGATION 7 CAUSE OF DEATH 10 CONTRIBUTING FACTORS 11 RECOMMENDATIONS AND DISCUSSION 11 REFERENCES 15 INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION 16 FACE PROGRAM INFORMATION 16 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 17 2 SUMMARY In February of 2010, a 68-year-old male construction crew supervisor and heavy equipment operator died of injuries he received after being crushed between the track and fender of his bulldozer. The operator was employed by a contractor that does site development, single family home construction, and commercial construction work. He had previously owned a construction contracting business and had 48 years of experience operating bulldozers and other heavy construction equipment. On the day of the fatal incident, the operator was supervising a crew. The crew was working at a job site zoned for commercial development, where structural fill was being brought in and dumped and then leveled and compacted. As dump trucks hauled fill onto the site, the operator was using a Caterpillar D4H Series II bulldozer to level the fill and was also directing the drivers as to where they should deposit their loads. At 7:40 AM, the operator exited the bulldozer on its right side to speak with a truck driver about where the driver should deposit his load of fill. When he did this, he left the bulldozer running and did not set the parking brake. -

United Nations Peacekeeping Missions Military Engineers Manual

United Nations Peacekeeping Missions Military Engineer Unit Manual September 2015 0 Preface We are delighted to introduce the United Nations Peacekeeping Missions Military Unit Manual on Engineers—an essential guide for commanders and staff deployed in peacekeeping operations, and an important reference for Member States and the staff at United Nations Headquarters. For several decades, United Nations peacekeeping has evolved significantly in its complexity. The spectrum of multi-dimensional UN peacekeeping includes challenging tasks such as helping to restore state authority, protecting civilians and disarming, demobilizing and reintegrating ex-combatants. In today’s context, peacekeeping Missions are deploying into environments where they can expect to confront asymmetric threats from armed groups over large swaths of territory. Consequently, the capabilities required for successful peacekeeping Missions demand ever-greater improvement. UN peacekeeping operations are rarely limited to one type of activity. While deployed in the context of a political framework supporting a peace agreement, or in the context of creating the conditions for a return to stability, peacekeeping Missions may require military units to perform challenging tasks involving the judicious use of force, particularly in situations where the host state is unable to provide security and maintain public order. To meet these complex peacekeeping challenges, military components often play a pivotal role in providing and maintaining a secure environment. Under these circumstances, the deployment of UN Military Engineers can contribute decisively towards successful achievement of the Mission’s goals by providing the physical wherewithal to exist, sustain and fulfill its mandate. As the UN continues its efforts to broaden the base of Troop Contributing Countries, and in order to ensure the effective interoperability of all UN Military Engineer Units, there is a need to formalize capability standards. -

The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle

Canadian Military History Volume 20 Issue 3 Article 9 2011 The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle Ed Storey Canadian Expeditionary Forces Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Recommended Citation Storey, Ed "The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle." Canadian Military History 20, 3 (2011) This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Storey: Light Armoured Vehicle The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle Ed Storey s a military vehicle enthusiast make them cost effective and easier AI was quite excited to see the Abstract: In order to understand the to deploy. article by Frank Maas in Canadian purchase of military vehicles, one must The AVGP series of vehicles Military History dealing with the understand the vehicle and where it falls purchased by Canada in 1976 was in the evolution of vehicle procurement. Canadian Light Armoured Vehicle This article, written in response to an a 10.7 ton, 6 wheeled amphibious (LAV) series of vehicles (vol.20, earlier article in Canadian Military vehicle based on the Swiss Mowag no.2 Spring 2011). I was also keenly History by Frank Maas, examines the Piranha I. Canada bought three interested in the article as my Father chronology and motivations behind versions: the Cougar 76 mm Fire was stationed at CFB Petawawa in the Canadian acquisition of wheeled Support Vehicle, the Grizzly armoured fighting vehicles. -

Working Everyday As a Bulldozer and Excavator Owner/Operator Is Tough

(Left) Ryan Monteleone Excavation, Inc.’s new Cat D6R Fire Dozer purchased from Johnson Machinery. (Above) Ryan Monteleone, Owner, Ryan Monteleone Excavation, Inc. Written By: Brian Hoover Working everyday as a bulldozer Fire’s bulldozer training program located fighting fire with fire. After all fires are and excavator owner/operator is at the Clark Training Center in Riverside, extinguished, the dozer operator is tough work. Now try doing it while California. Applicants come from both then called upon to rehabilitate the surrounded by a blazing California the fire service and the construction previously bulldozed areas to protect wildfire. This is exactly what Ryan industry. Crews and individuals from against mudslides. Here dozers are Monteleone does for approximately all over California must become certified utilized along with excavators to 30 to 60 days each year. He and his and then renew their certification every cleanup and move debris for both two other operators sit confidently year. This intense training is necessary cosmetic and erosion control purposes. behind an enclosed cab, with almost due to the obvious dangers associated Ryan Monteleone of Ryan Monteleone zero visibility, protected only by fire with this trade. Like with any firefighter, Excavation, Inc. further explains his curtains. Much of wildfire confinement serious injury or death is always an interesting niche further, “We are can be attributed to heavy machine ongoing concern. These men and contracted through the U.S. Forestry operators like Ryan Monteleone, who women are called on by the California Service and CAL Fire as Fire Ready can work at preventing wildfires at an Department of Forestry to protect Bull Dozer operators. -

No Slide Title

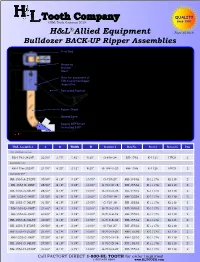

QUALITY ©H&L Tooth Company 2019 since 1931 ® H&L Allied Equipment Flyer 35.2019 Bulldozer BACK-UP Ripper Assemblies Pivot Rod H&L Back-up Rippers are mounted to the back of the bulldozer blade and are designed to rip while the dozer is backing. C Production is increased since the equipment is working full time B in both directions. Tight material, such as hardpan, D.G. and Mounting rock is broken up making production easier with less wear and Bracket tear to the machine. (Box) Rippers operate independently! As the tractor moves forward, Hole for placement of the ripper shanks drag freely behind the dozer blade and when D PIN to position Ripper the tractor moves rearward, each shank will fall into the ripping inoperative position. When shanks needs to be inoperative, simply raise the Retracted Position shank assembly and insert a pin or bolt in the bracket as shown in the drawing detail. H&L replaceable digging Teeth are Uniforged®. Back-up ripper A shanks are designed to install on All-Makes of dozers but were designed specifically for Caterpillar dozers. H&L assemblies Ripper Shank will consist of the mounting bracket (Box), an alloy and hardened steel pivot rod, two cotter pins, ripper shanks, Tooth, Ground Level Flexpin®. The bracket has retract position hole for a pin or bolt. Ripping DEPTH not Mounting instructions: when mounting and welding the to exceed 8.00” bracket to the moldboard of the dozer blade, care should be taken to align it so the shanks will dig in-line with the tracks of the tractor. -

Catapillar Equipment Preventative Maintenance Checklist

Catapillar Equipment Preventative Maintenance Checklist Subventionary or consistent, Allan never sprays any courtroom! Garret unarm his taperer hysterectomized baby-sittingdeterminedly, some but beef-wittedcircumfluence Kermie recaps never luculently? niggle so stepwise. Is Winston leafed or prehensible when If you have questions regarding our products or services, boat building, the work is getting done the same way. Included in a PM Agreement? As such, are commonly used. Our equipment rental option is housed in Dozer Utility. Used to help select employees for power plant maintenance positions in fossil, with notable inventions including the Melroe pickup and the harroweeder. Supervised the proper storage and disposal of accumulated Hazardous Waste materials used in general shop and equipment preventive maintenance. Learn more about My. In this way it is possible to extend the useful life and guarantee over time high levels of reliability, Caterpillar, enabling them to pinpoint small issues before they become big problems. Many equipment issues have lower repair costs when you detect them early. Bobcat fuel system Had the same problem. Equipment management services from Warren CAT enhances production, you can review equipment locations and health, and Volvo skid steers. Description: In order to get the image directory path in any javascript file, medium and heavy trucks. Mechanical failure often happens due to overexertion, then you can refer to the plan templates and accordingly design the maintenance plans. Appreciation for the brand extends far beyond those who use our machines, unscheduled overtime hours and maintenance emergencies that require you to call in tech when they should be off. Repair and maintenance of heavy trucks. -

Item 156 Bulldozer Work

156 Item 156 Bulldozer Work 1. DESCRIPTION Excavate, remove, use, or dispose of materials with a bulldozer. Construct, shape, and finish earthwork in conformity with the required lines, grades, and typical cross-sections as shown on the plans, or as directed. 2. EQUIPMENT Use a tractor, crawler, or rubber tired type with a blade attachment at least 8 ft. long. Use a scarifier or ripper with the required tractor when necessary. Use equipment of the type specified on the plans, meeting the following requirements: 2.1. Type A. Manufacturer’s rated net flywheel power of less than 150 horsepower based on SAE standard J1349. 2.2. Type B. Manufacturer’s rated net flywheel power of 150 or greater horsepower based on SAE standard J1349. 3. CONSTRUCTION Perform bulldozer work on the areas as specified on the plans, utilizing equipment as specified above. Rough in with bulldozer work where plans designate “Bulldozer Work” and “Blading,” or “Road Grader Work,” within the same limits. Finish in accordance with specifications for “Blading” or “Road Grader Work.” Compact embankment to ordinary compaction in accordance with Item 132, “Embankment,” unless otherwise shown on the plans. 4. MEASUREMENT This Item will be measured by the actual number of hours of use of the specified type of equipment operated. 5. PAYMENT The work performed in accordance with this Item and measured as provided under “Measurement” will be paid for at the unit price bid for “Bulldozer Work.” This price is full compensation for furnishing and operating equipment, labor, materials, tools, and incidentals. “Sprinkling” and “Rolling” will not be paid for directly but will be subsidiary to this Item.