Filming Pakistan in Zero Budget

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Elite Culture by Pakistani Tv Channels ______

PROMOTING ELITE CULTURE BY PAKISTANI TV CHANNELS ___________________________________________________ _____ BY MUNHAM SHEHZAD REGISTRATION # 11020216227 PhD Centre for Media and Communication Studies University of Gujrat Session 2015-18 (Page 1 of 133) PROMOTING ELITE CULTURE BY PAKISTANI TV CHANNELS A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of Degree of PhD In Mass Communications & Media By MUNHAM SHEHZAD REGISTRATION # 11020216227 Centre for Media & Communication Studies (Page 2 of 133) University of Gujrat Session 2015-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am very thankful to Almighty Allah for giving me strength and the opportunity to complete this research despite my arduous office work, and continuous personal obligations. I am grateful to Dr. Zahid Yousaf, Associate Professor /Chairperson, Centre for Media & Communication Studies, University of Gujrat as my Supervisor for his advice, constructive comments and support. I am thankful to Dr Malik Adnan, Assistant Professor, Department of Media Studies, Islamia University Bahawalpur as my Ex-Supervisor. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Farish Ullah, Dean, Faculty of Arts, whose deep knowledge about Television dramas helped and guided me to complete my study. I profoundly thankful to Dr. Arshad Ali, Mehmood Ahmad, Shamas Suleman, and Ehtesham Ali for extending their help and always pushed me to complete my thesis. I am thankful to my colleagues for their guidance and support in completion of this study. I am very grateful to my beloved Sister, Brothers and In-Laws for -

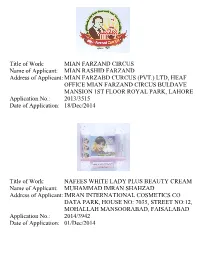

Mian Farzabd Curcus

Title of Work: MIAN FARZAND CIRCUS Name of Applicant: MIAN RASHID FARZAND Address of Applicant: MIAN FARZABD CURCUS (PVT.) LTD, HEAF OFFICE MIAN FARZAND CIRCUS BULDAVE MANSION 1ST FLOOR ROYAL PARK, LAHORE Application No.: 2013/3515 Date of Application: 18/Dec/2014 Title of Work: NAFEES WHITE LADY PLUS BEAUTY CREAM Name of Applicant: MUHAMMAD IMRAN SHAHZAD Address of Applicant: IMRAN INTERNATIONAL COSMETICS CO DATA PARK, HOUSE NO: 7035, STREET NO:12, MOHALLAH MANSOORABAD, FAISALABAD Application No.: 2014/3942 Date of Application: 01/Dec/2014 Title of Work: WHITE LADY BEAUTY CREAM Name of Applicant: MUHAMMAD IMRAN SHAHZAD Address of Applicant: WHITE LADY INTERNATIONAL DATA PARK, HOUSE NO: 7035, STREET NO:12, MOHALLAH MANSOORABAD, FAISALABAD Application No.: 2014/3943 Date of Application: 01/Dec/2014 Title of Work: WHITE GIRL INTERNATIONAL Name of Applicant: MUHAMMAD IMRAN SHAHZAD Address of Applicant: IMRAN INTERNATIONAL COSMETICS CO DATA PARK, HOUSE NO: 7035, STREET NO:12, MOHALLAH MANSOORABAD, FAISALABAD Application No.: 2014/3944 Date of Application: 01/Dec/2014 Title of Work: ISLAMIC INSTITUTE FOR EDUCATION Name of Applicant: SYED MUHAMMAD YOUSUF HASSAN TAHIR Address of Applicant: ISLAMIC INSTITITE FOR EDUCATION, SABEEL WALI MASJID, GRUMANDER, KARACHI Application No.: 2014/3945 Date of Application: 01/Dec/2014 Title of Work: ABC POTATO SNACKS Name of Applicant: MUHAMMAD KHALID KHAN Address of Applicant: SITARA PRODUCTS PAKISTAN., C-261/5, QUICE ROAD, SUKKUR Application No.: 2014/3946 Date of Application: 08/Dec/2014 Title of Work: MR. -

Emergent Cinema of Pakistan

Bāzyāft-30 (Jan-Jun 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 13 Emergent Cinema of Pakistan Ahmad Bilal ABSTRACT: Pakistan and India shared a common history, language and cultural values, so the form of the film is also similar. The biggest challenge for Pakistan film industry (Lollywood), since partition in 1947, was to achieve a form that can formulate its unique identity. Indian films had been facing an official ban from 1960s to 2007, which initially had helped the local film industry, as, in 1970s and 80s, it was producing more than 100 films per year. However, the ban had diminished the competition and become the biggest reason of the decline of Pakistani film. The number of films and their production value had been deteriorating in the last two decades. In 2007, the official screening Indian films have been allowed by Pakistani authorities. It, on the one side, has damaged the traditional films, “established cinema”, of Pakistan, and on the other side, it has reactivated the old question of distinctive cultural face of Pakistan. Simultaneously, the technology has been shifted from analogue to digital, which have allowed young generation of moviemakers to experiment with the medium, as it is relatively economical. The success of Khuda Kay Liay (2007) and Bol (2011) have initiated a new kind of cinema, which is termed as “emergent cinema” by this research. This paper investigates emergent cinema to define its elements and to establish its relation with the established cinema of Pakistan. It also discloses the link of emergent cinema with the media liberation Act of 2002, which has allowed a range of subjects. -

Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report

Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report January – March 2013 KASHF FOUNDATION 19 Aibak Block New Garden Town Lahore Pakistan +92 – 42- 111-981-981 www.kashf.org Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report Jan – March 2013 Major Highlights Kashf Foundation launches a TV Drama on HUM TV primetime. The TV show focuses on issues plaguing low-income women in Pakistan and shows a way out of poverty and dis-empowerment through microfinance that specially caters to women entrepreneurs! Kashf is Pakistan’s first microfinance institution to ever produce and launch a TV show on primetime! www.facebook.com/RehaiiOfficial Kashf Closes the Current Quarter with an Active Client Base of 305,940 clients and an outstanding portfolio of Rs. 3.4 Billion. Kashf Foundation maintains an OSS of 107 and FSS of 97% Kashf Improves Employees Gender Ratio from 48% to 49% March2013 – | January Operational Performance 1 Overall Growth Kashf Foundation ended the period January - March 2013 with an active clientele of 305,940 clients with an outstanding portfolio of Rs. 3.4 billion, compared with 300,091 clients and an outstanding portfolio of Rs. 3.2 billion at December 2012 closing. Kashf was able to maintain the growth rate of the previous quarter despite the myriad issues facing the economy, political 1 Figures in this for Quarter 3 are audited figures, which may vary from the unaudited figures provided in the Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report previous quarterly report. 1 turbulence, and security concerns. The number of loans disbursed in the quarter were also maintainted, i.e. 53,372 loans in the current quarter compared to 54,244 loans in the previous quarter. -

ICI PAKISTAN LIMITED Interim Dividend 78 (50%) List of Shareholders Whose CNIC Not Available with Company for the Year Ending June 30, 2015

ICI PAKISTAN LIMITED Interim Dividend 78 (50%) List of Shareholders whose CNIC not available with company for the year ending June 30, 2015 S.NO. FOLIO NAME ADDRESS Net Amount 1 47525 MS ARAMITA PRECY D'SOUZA C/O AFONSO CARVALHO 427 E MYRTLE CANTON ILL UNITED STATE OF AMERICA 61520 USA 1,648 2 53621 MR MAJID GANI 98, MITCHAM ROAD, LONDON SW 17 9NS, UNITED KINGDOM 3,107 3 87080 CITIBANK N.A. HONG KONG A/C THE PAKISTAN FUND C/O CITIBANK N.A.I I CHUNDRIGAR RD STATE LIFE BLDG NO. 1, P O BOX 4889 KARACHI 773 4 87092 W I CARR (FAR EAST) LTD C/O CITIBANK N.A. STATE LIFE BUILDING NO.1 P O BOX 4889, I I CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI 310 5 87147 BANKERS TRUST CO C/O STANDARD CHARTERED BANK P O BOX 4896 I I CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI 153 6 10 MR MOHAMMAD ABBAS C/O M/S GULNOOR TRADING CORPORATION SAIFEE MANZIL ALTAF HUSAIN ROAD KARACHI 64 7 13 SAHIBZADI GHULAM SADIQUAH ABBASI FLAT NO.F-1-G/1 BLOCK-3 THE MARINE BLESSINGS KHAYABAN-E-SAADI CLIFTON KARACHI 2,979 8 14 SAHIBZADI SHAFIQUAH ABBASI C/O BEGUM KHALIQUAH JATOI HOUSE NO.17, 18TH STREET KHAYABAN-E-JANBAZ, PHASE V DEFENCE OFFICERS HOUSING AUTHO KARACHI 892 9 19 MR ABDUL GHAFFAR ABDULLAH 20/4 BEHAR COLONY 2ND FLOOR ROOM NO 5 H ROAD AYESHA BAI MANZIL KARACHI 21 10 21 MR ABDUL RAZAK ABDULLA C/O MUHAMMAD HAJI GANI (PVT) LTD 20/13 NEWNAHM ROAD KARACHI 234 11 30 MR SUBHAN ABDULLA 82 OVERSEAS HOUSING SOCIETY BLOCK NO.7 & 8 KARACHI 183 12 50 MR MOHAMED ABUBAKER IQBAL MANZIL FLAT NO 9 CAMPBELL ROAD KARACHI 3,808 13 52 MST HANIFA HAJEE ADAM PLOT NO 10 IST FLOOR MEGHRAJ DUWARKADAS BUILDING OUTRAM ROAD NEAR PAKISTAN -

Causes and Effects of Indian Movies in Pakistani Cinemas

CAUSES AND EFFECTS OF INDIAN MOVIES IN PAKISTANI CINEMAS: A CASE STUDY OF LAHORE Researcher Supervisor Muhammad Umar Nazir Prof. Dr. Ghulam Shabir Reg. No. 02/M.Phil-2/2011 Chairman M. Phil (Media Studies) Department of Media Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirement of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Media Studies (Session 2011-2013) Department of Media Studies The Islamia University of Bahawalpur i Table of Contents Sr. Contents Page No No. Abstract 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Rationale of Study 9 1.2.1. Rationale for Selecting the Topic 9 1.3 Objectives 11 1.4 Hypothesis 12 1.5 Research Questions 12 1.6 Significance 13 Chapter 2: Literature Review 2.1 Literature Review 16 Chapter 3: Theoretical Framework 3.1 Theoretical Framework 33 3.2 Uses and Gratification Theory 33 3.2.1. Criticism of Uses and Gratification Theory 36 3.2.2. Relevance of the Theory with Research 37 3.3 Theory of Political Economy of Communication 37 3.3.1 Roots 39 3.3.2. Political economy of communication in Nazi Germany 46 viii 3.3.3. Contemporary concerns 49 3.3.4. Contemporary “mainstream” approaches 50 3.4 Conclusion 61 Chapter 4: Research Methodology 4.1 Research Design 62 4.2 Research Methodology 63 4.2.1. Universe 63 4.2.2. Sampling 64 4.2.3. Sampling Ratio 64 4.2.4. Sample Size 65 4.3. Unit of Analysis 65 4.4. Conceptualization and Operationalization of key terms and concepts 67 4.4.1. -

The AASHA Experience

The AASHA Experience A Decade of Struggle Against Sexual Harassment in Pakistan Fouzia Saeed (Director, Mehergarh) Rafiq Jaffer (Director, Institute of Social Science Lahore) Sadaf Ahmad (Assistant Professor of Anthropology, LUMS) Renate Frech (International Civil Servant) Main Coordinators: Maliha Husain & Khadija Ali MEHERGARH RESEARCH AND PUBLICATIONS Islamabad, Pakistan Cover Design: Sonia Rafique Photographs: Sajid Munir Printed by: Visionaries Division Copyrights @2011: All rights reserved by Mehergarh: A Center for Learning. ISBN: ----------- 22 December, 2011 Contents Preface 6 Abbreviations and Acronyms 7 1. The Initial Years (2001-2002) 9 1.1. The Beginnings of AASHA 9 1.2. The Official Launching of AASHA 10 1.3. Situation Analysis of Sexual Harassment at the Workplace 12 1.4. Guidelines for Creating a Working Environment Free of Discrimination and Harassment 12 1.5. Developing the Code of Conduct for Gender Justice at the Workplace 13 1.6. The Government Decides to Adopt the Code as an Employer 15 2. Shift of Policy Cooperation with the Private Sector (2002-2003) 17 2.1. Taking the Code to the Private Sector 17 2.2. The AASHA Annual Award Ceremonies, 2002-2003 18 2.3. Training Activities, 2002-2003 19 2.4. Media Campaigns, 2002-2003 19 2.5. AASHA Annual Assemblies of Working Women, 2002-2003 20 2.6. AASHA's Internal Processes, 2002-2003 20 3. Re-engaging with the Government while Continuing working with the Private Sector (2004-2006) 22 3.1. Going Back to Government 22 3.2. The Civil Service Disciplinary Rules (ESTA Code) 22 3.3. The Education and Labour Sectors 24 3.4. -

Role of ISPR in Countering Hybrid Warfare

Human Nature Journal of Social Science Vol. 1, No. 1 (March-2021), Pp.12-21 Role of ISPR in Countering Hybrid Warfare Zainab Khan1, Abdul Wajid Khan2 1MPhil Media Studies, Department of Media Studies, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur 2Professor, Department of Media Studies, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur [email protected], [email protected] Abstract In recent years, hybrid warfare has come up as a real challenge for states especially, the ones which are developing like Pakistan and tensions of hybrid warfare due to some allegations from Indian media. The relationship between both Pakistan and India becomes more complicated; therefore, this research study is designed to find out the role of ISPR towards handling of national media in the prevalent security environment with a view to recommend measures to integrate both for larger national security interests. Therefore, according to the need of recent research study, researcher adopted the explorative research design and the population comprised of all the media production by ISPR and sample was collected by using purposive sampling technique. Moreover, ISPR is in principle, an authoritative military media and the study explore the role of ISPR being media and public relations wing of the Pakistan armed forces and the main source of information in point of view of hybrid warfare and in spreading awareness regarding hybrid warfare are the findings gathered from content analysis of the media campaigned. The findings revealed that the purpose behind the creation of such content was to paid homage to the brave soldiers of armed forces of the land of Pakistan and also falsified the propaganda impose by foreign media to spread rumors against Pakistan. -

Citizenship and State in Pakistani Animated Films Mohammad Azeem

Animating Subjects: Citizenship and State in Pakistani Animated Films Mohammad Azeem Abstract This paper engages in textual analysis of 3 Bahadur (dir. Sharmeen O. Chinoy, 2015) and Allahyar and The Legend of the Markhor (dir. Uzair Zaheer Khan, 2018) to explore the portrayal of archetypal good and evil, the ideal male and female citizen, and the depiction of the enemy. The analysis is built upon the idea of ‘politics of innocence’ and the relationship of films with the audience's deep-rooted concerns about life. In this case, all the questions that arise from engaging with the aforementioned themes. The paper finds that while in 3 Bahadur, the ideal citizen embraces the power to fight the enemy that takes birth within the community, Allahyar and The Legend of the Markhor (ALM) pictures the enemy as someone residing outside the country and portrays Allahyar as the ‘Protector’. It also finds a different treatment of female protagonists in both films; where Mehru in ALM, though adventurous, is trapped by guilt for being one while Amna in 3 Bahadur, is supported by his father to fight off the villain. This analysis is primarily necessitated by the idea of innocence, employed by selected films, to scrutinize the didactic messaging which would otherwise go unchecked, for the innocence gives the tinge of ‘unintentional’ design making it more persuasive for the audience. Keywords: Pakistani Animation, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, Uzair Zaheer Khan, Citizenship, Nation in Cinema The Pakistani cinema industry took a brutal hit during the martial law era of dictator Zia-ul-Haq, beginning in 1977 (Gazdar). -

The Complete Magazine for the Region October 2019

The Complete Magazine for the Region OCTOBER 2019 www.southasia.com.pk Afghanistan Afg. 50 Australia A$ 6 Bangladesh Taka 100 Bhutan NU 50 Brazil BRL 20 Canada C$ 6 China RMB 30 France EUR 45 Hong Kong HK$ 30 India Rs. 100 Japan ¥ 500 Korea Won 3000 Malaysia RM 6 Maldives Rf 45 Myanmar MMK10 Nepal NcRs. 75 New Zealand NZ$ 7 Pakistan Rs. 200 Philippines P 75 Saudi Arabia SR 15 Singapore S$ 8 Sri Lanka Rs. 100 WHITHER Thailand B 100 Turkey Lira. 2 UAE AED 10 UK £ 3 USA $ 5 WORLD BANK? Despite massive funding, the World Bank has not been able to achieve its mission to eradicate poverty in South Asian countries. PAKISTAN INDIA AFGHANISTAN YEMEN FATA Integration Kashmir Crisis Uncomfortable Truth End Game SOUTHASIA • OCTOBER 2019 3 CONTENTS 16 Cover Story The World Bank's project financing impact should have more visibility. Waziristan Dhaka Editor’s Desk 07 Challenges of Integration 33 About Face 40 Readers’ Thoughts 08 Kabul Kartarpur Elusive Solution 34 The Sikh Card 41 Who Said That! 10 Damp Squib 36 Neighbour Grapevine 11 Srinagar Drums of War 38 Beijing News Buzz 12 Titanic War 44 Cover Story World Bank Relevance 16 Interview - Zarrar Sehgal 18 Development Agenda 21 Facing the Challenges 23 The Trickle-Up Effect 27 Region Islamabad - New Delhi Signals Game 30 Islamabad Deficit Paradigm 31 30 4 SOUTHASIA • OCTOBER 2019 SLUG 40 49 45 47 53 Kuala Lumpur Mumbai Reality and Hope 45 Muddled Minds 54 54 International Colombo Price of Indiscipline 56 Aden End Game 47 Around Town Feature Khaadi – All Tressed Up 58 Lahore Aviator 8 Limited Edition 58 Celebrating the Real Pakistan 48 Reviews Death of a System 49 Books Islamabad Constitutional and Political Setback for Pakistani doctors 50 History of Pakistan 59 Malé Kashmir as I See It 60 Paradise Lost 51 Films Kabul Aladdin 61 Violence Against Women 53 47 Meters Down: Uncaged 62 SOUTHASIA • OCTOBER 2019 5 EDITor’s DESK A Passionate Appeal The situation prevailing in Jammu & self-determination to the people of Kashmir. -

Pakistan's Institutions of Higher Education Impacting Community

Issue V CommPact Spring 2016 Pakistan’s Institutions of Higher Education Impacting Community through PCTN CommPact A PCTN Publication Spring 2016 In Focus 05 Advocacy/ Awareness 11 Health 19 Education 29 CHAPTERS Disaster Relief 41 Environment Protection 45 Community Empowerment and Outreach 49 Misc News 57 Editor > Gul-e-Zehra Graphics & layout > Kareem Muhammad PSA Directorate-NUST Editor’s Note I am pleased to share with you the 5th edition of Pakistan Chapter of The Talloires tual learning for students. Network (PCTN) newsletter. Like the previous newsletters, this publication also In March 2016 the 3rd PCTN seminar was held on the theme of ‘Role of Universities shares the outstanding community service work being carried out by students of in Community Development and Empowerment’. It was attended by Vice Chancel- PCTN member universities all across Pakistan. The activities that our members share lors, faculty and students of PCTN member universities. Rector NUST Engr Muham- motivate us to do better in reaching out to and serving our communities. mad Asghar and Air Commodore Shabbir gave key note speeches, which inspired At the end of last year PCTN members elected a new Steering Committee for the the attendees to make all possible efforts for the betterment of Pakistan. A panel next 2 years. We hope that the leadership of the newly elected committee would discussion on ‘Contributions towards school education’ was held. After the seminar, guide and steer the Chapter towards promoting the cause of community service meeting of the newly elected Steering Committee was also held in which the way throughout Pakistan. -

An Interview with the Team of Maalik by Ally Adnan

An Interview with the Team of Maalik by Ally Adnan After a period of more than three decades, cinema in Pakistan is now in the midst of a revival. Films like Chambaili, Dukhtar, Josh, Lamha, Main Hoon Shahid Afridi, Na Maloom Afraad, Waar, Khuda Ke Liye, Tamanna and Zinda Bhaag have received both commercial and critical success, paving the way for an unprecedented number of serious films that is in the pipeline for the next few years. Ashir Azeem’s Maalik is one of the more promising films in this list of films. In an exclusive interview for the Friday Times, Ally Adnan talks to film’s director, Ashir Azeem, and his wife, Bushra Ashir, along with two of its stars, Farhan Ally Agha and Hassan Niazi. 1. Cinema in Pakistan seems to have a new lease on life and the resurgence has made it possible for a lot of new filmmakers to join the field and produce films of a superior caliber. Maalik is one of the major films that is set for a release in 2015. Would the film have been made if Pakistani cinema was not undergoing a revival? Ashir Azeem: I believe the film would have been made, if not now, then in a few years. The activity in the field of cinema made it possible to make it now. Farhan Ally Agha: I want to say something about the so-called “resurgence” of Pakistani cinema. I do not feel that it is as much a resurgence as it is a complete rebirth. The cinema that was in vogue up until the nineteen eighties was very different than what we have today.