The Established Cinema of Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Elite Culture by Pakistani Tv Channels ______

PROMOTING ELITE CULTURE BY PAKISTANI TV CHANNELS ___________________________________________________ _____ BY MUNHAM SHEHZAD REGISTRATION # 11020216227 PhD Centre for Media and Communication Studies University of Gujrat Session 2015-18 (Page 1 of 133) PROMOTING ELITE CULTURE BY PAKISTANI TV CHANNELS A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of Degree of PhD In Mass Communications & Media By MUNHAM SHEHZAD REGISTRATION # 11020216227 Centre for Media & Communication Studies (Page 2 of 133) University of Gujrat Session 2015-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am very thankful to Almighty Allah for giving me strength and the opportunity to complete this research despite my arduous office work, and continuous personal obligations. I am grateful to Dr. Zahid Yousaf, Associate Professor /Chairperson, Centre for Media & Communication Studies, University of Gujrat as my Supervisor for his advice, constructive comments and support. I am thankful to Dr Malik Adnan, Assistant Professor, Department of Media Studies, Islamia University Bahawalpur as my Ex-Supervisor. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Farish Ullah, Dean, Faculty of Arts, whose deep knowledge about Television dramas helped and guided me to complete my study. I profoundly thankful to Dr. Arshad Ali, Mehmood Ahmad, Shamas Suleman, and Ehtesham Ali for extending their help and always pushed me to complete my thesis. I am thankful to my colleagues for their guidance and support in completion of this study. I am very grateful to my beloved Sister, Brothers and In-Laws for -

The Pakistan National Bibliography 2012

THE PAKISTAN NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 2012 A Subject Catalogue of the new Pakistani books deposited under the provisions of Copyright Law or acquired through purchase, etc. by the National Library of Pakistan, Islamabad, arranged according to the Dewey Decimal Classification, 23rd edition and catalogued according to the Anglo American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd revised edition, 1988, with a full Author, Title, Subject Index and List of Publishers. Government of Pakistan Department of Libraries National Library of Pakistan Constitution Avenue, Islamabad © Department of Libraries (National Bibliographical Unit) 2013 Patron : Ch. Muhammad Nazir, Director General Compiler : Nida Mushtaq, Assistant Editor Composer : Muhammad Nazim Price Within Pakistan Rs. 1300.00 Outside Pakistan .US $ 60.00 ISSN 1019-0678 ISBN 978-969-8014-46-9 Cataloguing in Publication 015.5491 Pakistan. Department of Libraries , Islamabad The Pakistan National Bibliography 2012 / ed. by Nida Mushtaq.— Islamabad : The Authority, 2013. 500p. ; 24cm : Rs. 1300 ISBN 978-969-8014-46-9 1. Bibliography, National — Pakistan I. Editor II. Title (ii) PREFACE A National Bibliography is a mirror in which intellectual and literary trends of a nation can be seen very clearly. On the basis of this reflection, the intellegencia can envision the future heights and goals of a nation. Keeping in mind the importance of National Bibliography, this issue has been compiled, edited and published by National Library of Pakistan, Department of Libraries, Islamabad. This volume includes all the books received in National Library of Pakistan under depository provision of prevailing copyright law of Pakistan. It also includes Pakistani publications acquired through purchase, gifts and exchange basis. However following type of material has not been included: a. -

Pdf (Accessed: 3 June, 2014) 17

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 The Production and Reception of gender- based content in Pakistani Television Culture Munira Cheema DPhil Thesis University of Sussex (June 2015) 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted, either in the same or in a different form, to this or any other university for a degree. Signature:………………….. 3 Acknowledgements Special thanks to: My supervisors, Dr Kate Lacey and Dr Kate O’Riordan, for their infinite patience as they answered my endless queries in the course of this thesis. Their open-door policy and expert guidance ensured that I always stayed on track. This PhD was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. My mother, for providing me with profound counselling, perpetual support and for tirelessly watching over my daughter as I scrambled to meet deadlines. This thesis could not have been completed without her. My husband Nauman, and daughter Zara, who learnt to stay out of the way during my ‘study time’. -

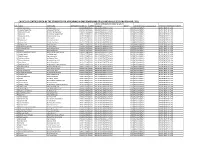

Part - I Exam) for the Post Tgt (Natural Science ) Female, Post Code - 08/10 (Date of Examination - 19.06.2010

COMPLET MERIT LIST (PART - I EXAM) FOR THE POST TGT (NATURAL SCIENCE ) FEMALE, POST CODE - 08/10 (DATE OF EXAMINATION - 19.06.2010) Cut off Category marks UR 119 OBC 104 SC 84 OH 98 Sub- MARKS Shortlisted S.No. ROLLNO IDNO NAME FNAME DOB Cat. Cat. (Part-I) in 1 00819406 00482097 PARAMJIT KAUR MANMEET SINGH 290580 UR 148 S-GEN 2 00811330 00402941NIDHI GOYAL ASHISH GOYAL 280685 UR 146 S-GEN 3 00820040 00638488MANISHA ANAND PRAKASH 091085 UR 146 S-GEN 4 00818974 00649247 PARUAL ARUN KUMAR 190184 UR 144 S-GEN 5 00810918 00668290 ANDEEP KAUR MANMOHIT PAL SINGH 071077 UR 143 S-GEN 6 00818422 00606647 RITA HARSH KUMAR CHUTANI 190878 UR 142 S-GEN 7 00815218 00629894 LALITA TEJ RAM DHARIWAL 200978 UR 142 S-GEN 8 00813598 00408403PURTI JAIN MANISH JAIN 150780 UR 142 S-GEN 9 00818057 00475966USHA KHULBE LILADHAR 051180 UR 142 S-GEN 10 00814956 00502474 TULIKA SINGH RAJENDER SINGH RATHEE 100584 OBC/GO 142 S-GEN 11 00816828 00668345 NEERA SINGH RAMESH KUMAR SINGH 011074 UR/GO 141 S-GEN 12 00812481 00409432 JYOTSANA MANGAL AMIT KUMAR MANGAL 061280 UR 141 S-GEN 13 00820897 00606389 GARG SACHIN GUPTA 191282 UR 141 S-GEN 14 00810041 00606310 NEERU MEHTA DINI NATH MEHTA 200783 UR 141 S-GEN 15 00812406 00403602 NEHA SHARMA SHASHI BHUSHAN SHARMA 231184 UR/GO 141 S-GEN 16 00813445 00482442GARIMA GUPTA RAJ KUMAR 140485 UR 141 S-GEN 17 00816296 00420805 ANITA KUMARI MAHINDRA SAT PAUL 280974 UR 140 S-GEN 18 00821024 00418099 SHELLY JAIDKA PAL KRISHAN JAIDKA 130278 UR 140 S-GEN 19 00811356 00407751 SAVITA GUPTA DEVESH GUPTA 041278 UR 140 S-GEN 20 00821941 00421597 -

Choice of Centres Given by the Students for LLB and BALLB End

CHOICE OF CENTRES GIVEN BY THE STUDENTS FOR APPEARING IN END SEM EXAMS OF LLB AND BALLB SESSION: FEB-MAR, 2021 CHOOSE YOUR SEMESTER GROUP (in which S.No NAME PARENTAGE ENROLMENT (11 DIGITS) COURSE to appear ) BATCH CAPACITY (choose capacity group) CHOICE OF EXAMINATION CENTRE 1 Umar mohi u din Gh mohi u din 19042148004 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 2 huzaib ishtiyaq khan Ishtiyaq ahmed lhan 19042127121 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 3 Mehvish Manzoor Manzoor Ahmad baba 19042127120 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 4 Tabish Jan Mohammad yaseen bhat 19042127119 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2020 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 5 Sabreena Hassan Ghulam Hassan lone 19042127118 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 6 Huda Hilal Hilal Ahmad 19042127117 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 7 Rabia Rashid Abdul Rashid Bhat 19042127116 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 8 Sabiyarashid Abdulrashiddanga 19042127115 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 9 Tuibun u nisa Mohd Amin pir 19042127113 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 10 Shahid Hussain Baba Gh Mohd Baba 19042127111 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 11 Bilal Ahmad Shah Bashir Ahmad Shah 19042127110 BALLB BALLB 2ND SEMESTER ONLY 2019 REGULAR(ONLY) DEPARTMENT OF LAW 12 Sehreen Mushtaq Ahmad 19042127109 -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`I Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!Q

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!q Photo Credit: AP Photo/B.K. Bangash December 2014 ! Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence since 2007 Arif Rafiq! DECEMBER 2014 1 ! ! Contents ! ! I. Summary ................................................................................. 3! II. Acronyms ............................................................................... 5! III. The Author ............................................................................ 8! IV. Introduction .......................................................................... 9! V. Historic Roots of Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Conflict in Pakistan ...... 10! VI. Sectarian Violence Surges since 2007: How and Why? ............ 32! VII. Current Trends: Sectarianism Growing .................................. 91! VIII. Policy Recommendations .................................................. 105! IX. Bibliography ..................................................................... 110! X. Notes ................................................................................ 114! ! 2 I. Summary • Sectarian violence between Sunni Deobandi and Shi‘i Muslims in Pakistan has resurged since 2007, resulting in approximately 2,300 deaths in Pakistan’s four main provinces from 2007 to 2013 and an estimated 1,500 deaths in the Kurram Agency from 2007 to 2011. • Baluchistan and Karachi are now the two most active zones of violence between Sunni Deobandis and Shi‘a, -

Balochistan Review 2 2019

- I - ISSN: 1810-2174 Balochistan Review Volume XLI No. 2, 2019 Recognized by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan Editor: Abdul Qadir Mengal BALOCHISTAN STUDY CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA-PAKISTAN - II - Bi-Annual Research Journal “Balochistan Review” ISSN: 1810-2174 Publication of: Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. @ Balochistan Study Centre 2019-2 Subscription rate in Pakistan: Institutions: Rs. 300/- Individuals: Rs. 200/- For the other countries: Institutions: US$ 15 Individuals: US$ 12 For further information please Contact: Abdul Qadir Mengal Assistant Professor & Editor Balochistan Review Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Tel: (92) (081) 9211255 Facsimile: (92) (081) 9211255 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.uob.edu.pk/journals/bsc.htm No responsibility for the views expressed by authors and reviewers in Balochistan Review is assumed by the Editor, Assistant Editor, and the Publisher. - III - Editorial Board Patron in Chief: Prof. Dr. Javeid Iqbal Vice Chancellor, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Patron Prof. Dr. Abdul Haleem Sadiq Director, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Editor Abdul Qadir Mengal Asstt Professor, International Realation Department, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Assistant Editor Dr. Waheed Razzaq Assistant Professor, Brahui Department, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Members: Prof. Dr. Andriano V. Rossi Vice Chancellor & Head Dept of Asian Studies, Institute of Oriental Studies, Naples, Italy. Prof. Dr. Saad Abudeyha Chairman, Dept. of Political Science, University of Jordon, Amman, Jordon. Prof. Dr. Bertrand Bellon Professor of Int’l, Industrial Organization & Technology Policy, University de Paris Sud, France. Dr. Carina Jahani Inst. of Iranian & African Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Khan Director, Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. -

Filming Pakistan in Zero Budget

Filming Pakistan in Zero Budget Dr. Ahmad Bilal* ABSTRACT: In 2009-10, I have decided to do the doctorate in the art of filmmaking. Those were the years of extreme decline for Pakistan’s film industry. Pakistani film was almost over and there was no evidence of the resurrection of this destroyed industry. Indeed, the future of film industry was doubtful, and the same could be the case for a film researcher. Most of the friends, after knowing my field of research, often asked me that why would I chose to do PhD in the subject of film. As, according to them, this is one of the obnoxious and intolerable field, as it is ruining the society by offering and promoting sinful and immoral acts. So a PhD in such a field might not be fruitful in this world, as well as hereafter. I started thinking about one of the very basic questions that how this perception about the art of making film was built. The study of traditional Pakistani cinema, ‘established cinema’, has disclosed that the medium of film was facing a control from the very beginning. Indeed, the policy of censorship was rooted in the times of imperialism. The censorship policy of the British rule was executed only to restrain socialist political ideology and nationalistic themes (Pendakur 1996; Shoesmith 2009). The main emphasis of the policy focus of mass media systems during colonial regimes was on furthering administrative efficiency” (McMillin 71). The government of Pakistan had inherited the policies of their colonial masters; hence, they executed similar censorship policies even after Independence. -

Emergent Cinema of Pakistan

Bāzyāft-30 (Jan-Jun 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 13 Emergent Cinema of Pakistan Ahmad Bilal ABSTRACT: Pakistan and India shared a common history, language and cultural values, so the form of the film is also similar. The biggest challenge for Pakistan film industry (Lollywood), since partition in 1947, was to achieve a form that can formulate its unique identity. Indian films had been facing an official ban from 1960s to 2007, which initially had helped the local film industry, as, in 1970s and 80s, it was producing more than 100 films per year. However, the ban had diminished the competition and become the biggest reason of the decline of Pakistani film. The number of films and their production value had been deteriorating in the last two decades. In 2007, the official screening Indian films have been allowed by Pakistani authorities. It, on the one side, has damaged the traditional films, “established cinema”, of Pakistan, and on the other side, it has reactivated the old question of distinctive cultural face of Pakistan. Simultaneously, the technology has been shifted from analogue to digital, which have allowed young generation of moviemakers to experiment with the medium, as it is relatively economical. The success of Khuda Kay Liay (2007) and Bol (2011) have initiated a new kind of cinema, which is termed as “emergent cinema” by this research. This paper investigates emergent cinema to define its elements and to establish its relation with the established cinema of Pakistan. It also discloses the link of emergent cinema with the media liberation Act of 2002, which has allowed a range of subjects. -

Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report

Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report January – March 2013 KASHF FOUNDATION 19 Aibak Block New Garden Town Lahore Pakistan +92 – 42- 111-981-981 www.kashf.org Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report Jan – March 2013 Major Highlights Kashf Foundation launches a TV Drama on HUM TV primetime. The TV show focuses on issues plaguing low-income women in Pakistan and shows a way out of poverty and dis-empowerment through microfinance that specially caters to women entrepreneurs! Kashf is Pakistan’s first microfinance institution to ever produce and launch a TV show on primetime! www.facebook.com/RehaiiOfficial Kashf Closes the Current Quarter with an Active Client Base of 305,940 clients and an outstanding portfolio of Rs. 3.4 Billion. Kashf Foundation maintains an OSS of 107 and FSS of 97% Kashf Improves Employees Gender Ratio from 48% to 49% March2013 – | January Operational Performance 1 Overall Growth Kashf Foundation ended the period January - March 2013 with an active clientele of 305,940 clients with an outstanding portfolio of Rs. 3.4 billion, compared with 300,091 clients and an outstanding portfolio of Rs. 3.2 billion at December 2012 closing. Kashf was able to maintain the growth rate of the previous quarter despite the myriad issues facing the economy, political 1 Figures in this for Quarter 3 are audited figures, which may vary from the unaudited figures provided in the Kashf Foundation Quarterly Report previous quarterly report. 1 turbulence, and security concerns. The number of loans disbursed in the quarter were also maintainted, i.e. 53,372 loans in the current quarter compared to 54,244 loans in the previous quarter. -

Celebrations of National Book Day

CELEBRATIONS OF NATIONAL BOOK DAY Programme FIRST DAY Time Date Hall No. Activity 10 am to 9 22-4-2012 Entrance and Grand Book Fair pm Ist Floor 10 am to 22-4-2012 Auditorium Gogi Show: Gogi the Muppet will perform with 11.30 am the cartoonist Ms. Nigar Nazar about charm of reading. 11.30 am to 23-4-2012 Auditorium Funkor Child Art Center: Ms. Fouzia Aziz 1 pm Minallah will introduce Amai Roshni ki Chirya, a cartoon character she has developed for children. She will talk about her books and encourage children to write stories and make their own books. 1 pm to 2 pm 22-4-2012 Children Gogi activity: Gogi will distribute activity Activities Area sheets among children between ages 8-14 years. It will be a creative activity involving colouring/drawing/crossword general knowledge. Gogi books would be awarded to the winners. Story telling with live drawing on the spot. 1 to 2 pm 22-4-2012 Room No.204 The children of different schools including Global System of Integrated Studies School (GSIS) will meet renowned writers, artists, showbiz celebrities, etc. 2 pm to 9 pm 22-4-2012 Hall No.204 Book Reading Festival: 36 renowned authors, (Convocation artists, showbiz celebrities, etc. from all over Hall) Pakistan will participate in book reading festival. 1. Intiza Hussain 2. Attaul Haq Qasimi 3. Prof. Fateh Muhammad Malik 4. Mustansar Hussain Tarar 5. Mehmood Sham 6. Munnoo Bhai 7. Qavi Khan 8. Reema Khan 9. Talat Hussain 10. Iftikhar Arif 11. Asghar Nadim Syed 12.