And Red-Necked Grebes (Podiceps Grisegena)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(82) FIELD NOTES on the LITTLE GREBE. the Following Observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps R. Ruficollis) Were Made at Fetch

(82) FIELD NOTES ON THE LITTLE GREBE. BY P. H. TRAHAIR HARTLEY. THE following observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps r. ruficollis) were made at Fetcham Pond, near Leatherhead, in Surrey, during the last three years. TERRITORY. Little Grebes begin to defend territories in the middle of February. These are small areas—about |- acre—situated in the parts of the very shallow lake that are overgrown with marestail (Hippuris vulgaris). Where several territories border on an open space, free from weeds, this constitutes a neutral area where paired birds can meet and associate with others, without fighting. The actual territories are strictly protected. Both sexes defend their borders, sometimes working together. Terri torial demonstrations-—far more often than not they do not end in actual fighting—take place many times daily between pairs whose marches adjoin. One bird makes a series of short rushes towards his neighbours' territory, flapping his raised wings, and keeping his head and neck outstretched ; at the same time he utters the shrill, tittering call. The owner of the territory advances in the same set style ; between each rush, both birds float with heads drawn in, flank feathers fluffed out, and wings slightly raised. So they approach each other, until they float about a foot apart, and strictly on the territorial border. As they face one another, I have seen one, or both birds peck with an almost nervous movement at the surface of the water, as though picking something up. On one occasion the bird which had started the encounter splashed the water with its beak, and snatched at a weed stem. -

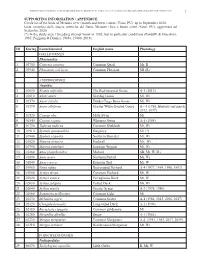

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Aberrant Plumages in Grebes Podicipedidae

André Konter Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae in grebes plumages Aberrant Ferrantia André Konter Travaux scientifiques du Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg www.mnhn.lu 72 2015 Ferrantia 72 2015 2015 72 Ferrantia est une revue publiée à intervalles non réguliers par le Musée national d’histoire naturelle à Luxembourg. Elle fait suite, avec la même tomaison, aux TRAVAUX SCIENTIFIQUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE DE LUXEMBOURG parus entre 1981 et 1999. Comité de rédaction: Eric Buttini Guy Colling Edmée Engel Thierry Helminger Mise en page: Romain Bei Design: Thierry Helminger Prix du volume: 15 € Rédaction: Échange: Musée national d’histoire naturelle Exchange MNHN Rédaction Ferrantia c/o Musée national d’histoire naturelle 25, rue Münster 25, rue Münster L-2160 Luxembourg L-2160 Luxembourg Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Fax +352 46 38 48 Fax +352 46 38 48 Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/ Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/exchange email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Page de couverture: 1. Great Crested Grebe, Lake IJssel, Netherlands, April 2002 (PCRcr200303303), photo A. Konter. 2. Red-necked Grebe, Tunkwa Lake, British Columbia, Canada, 2006 (PGRho200501022), photo K. T. Karlson. 3. Great Crested Grebe, Rotterdam-IJsselmonde, Netherlands, August 2006 (PCRcr200602012), photo C. van Rijswik. Citation: André Konter 2015. - Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae - An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide. Ferrantia 72, Musée national d’histoire naturelle, Luxembourg, 206 p. -

Leucistic Grebe Photo Identification

FEATURED PHOTO LEUCISTIC GREBE at MONO LAKE — AN IDENTIFICatION CHALLENGE LEN BLUMIN, 382 Throckmorton Ave., Mill Valley, California 94941; [email protected] From 12 to 15 October 2006 I observed and photographed a fully leucistic Podiceps grebe on Mono Lake, California. Subsequent study of the photographs raised questions about which species I had been watching and led to a review of how best to differentiate white-plumaged grebes. Mono Lake hosts more than 1.5 million Eared Grebes (Podiceps nigricollis) in October when most molt into basic plumage (Boyd and Jehl 1998). The grebes gorge on superabundant Mono Lake Alkali Flies (Ephydra hians) and Mono Lake Brine Shrimp (Artemia monica) before heading farther south for the winter (Cullen 1999). Within minutes of our arrival at Mono County Park in the mid-afternoon of 12 October 2006 Patti Blumin, my wife, spotted a white grebe, and we watched it for the next 30 minutes as it foraged at the surface and occasionally dove. The bird’s behavior differed from that of the neighboring Eared Grebes; it dived more frequently and oc- casionally swam like a merganser with just its head below the surface. We relocated and photographed the leucistic grebe on 14 and 15 October, and we later learned it had been spotted earlier by Jim Dunn on 7 October. Upon processing the digital photos, which I had taken at 30× magnification through a spotting scope, I quickly realized the bird’s structure was not typical of the Eared Grebe, showing instead many features of the Horned Grebe (P. auritus) described by Stedman (2000). -

Body Weights of Newly Hatched Anatidae.--As Early As 1928 (E

1965Oct. ] GeneralNotes 645 following day, Boulva found the bird again on the same territory, identified it posi- tively as a Le Conte's Sparrow (Passerherbuluscaudacutus), and photographed it with a 400 mm telephoto lens. On 23 July the second writer, after long observation, identified a Le Conte's Sparrow on the same territory. On 27 July Mr. Franqois Hamel, from "le Club des Ornithologues de Quebec," with Browne, had occasionto study the bird and its song; he too was convinced that the bird was a Le Conte's Sparrow. On 28 July both writers sighted two Le Conte's Sparrows together, captured one of the birds, and banded it (U.S.F.&W.S. band no. 52-39003, size 1). On 31 July, Mr. Raymond Cayouette, Curator of Birds at the Quebec Zoological Garden and President of "le Club des Ornithologuesde Quebec," with the Reverend Robert Plante of the same club, botb accompaniedby the first writer, were able to study the sparrow and were satisfied with the identification. On 11 August Browne caught a young Le Conte's Sparrow incapable of flight and banded it (band no. 103-42113, size 0), while two adults, one seen to be banded, were flying about. The young bird was well-feathered but had some down adhering to the plumage. The primaries were full grown except for the two outermost (pri- maries 8 and 9), which were short and still sheathed at the base. The tail feathers were well grown and pointed. The plumage was typical of the juvenal plumage of the species(see T. -

A PODICEPS PRIMER by Matthew L. Pelikan Wintertime Grebes Lack

A PODICEPS PRIMER by Matthew L. Pelikan Wintertime grebes lack charisma. They swim like logs and fly like windup toys. Their spectacular courtship choreography is months and hundreds of miles away. In dull winter plumage, even an Eared Grebe has a sort of check-it-off, go-warm-up-in-the-car quality. The marine habits of wintering grebes make close observation difficult. But bizarre life histories and intriguing behavior make Podiceps grebes appealing —once you get acquainted. Homed (in Europe known as Slavonia), Eared (i.e.. Black-necked), and Red-necked grebes share similar characteristics. Stubby wings, dense bodies, and rear-mounted feet make them more deft in water than on land or in flight. They breed mostly on shallow, weedy ponds well to the north. Sometimes isolated, sometimes colonial, their floating nests are attached to vegetation. During fall migration, grebes group at staging areas, then disperse to winter on lakes and sea coasts. Their opportunistic diet comprises invertebrates and fish, the latter more important in winter. All these grebes display considerable variability in appearance and behavior. But each species shapes this basic pattern into a unique form. The species of most interest to Massachusetts birders is the Eared Grebe (Podiceps nigricollis). Many readers no doubt enjoyed the very active Eared Grebe on Cape Ann during Febmary 1994. Birders who missed the show should not despair: this species is a rare but nearly annual visitor with about thirty state records (Veit and Petersen 1993). Reasonably, but without explanation, Harrison (1985) ascribes east-coast Eared Grebes to the North American subspecies (one of four worldwide), P. -

BREEDING of the LITTLE GREBE by G

THE S.A. ORNITHOLOGIST 109 BREEDING OF THE LITTLE GREBE By G. CLARKE. The following is a brief synopsis of events, continuously an agitated 'clip' or 'jip', a not altogether complete, of the breeding of single note. The nest was found to be a pair of Little Grebe (Podiceps nouaehol placed between a few sapling eucalypts 2 landiae) on the main dam at the Para Wirra to 3 feet in height, standing in the water, National Park, 20 miles NNE of Adelaide and was composed mainly of rush stems in the Mt. Lofty Ranges. (funcus) 'anchored' between the. saplings and The dam occupies an area of some two resembling a pile of. debris. The nest con and a half acres, and is situated at an tained three eggs, stained an ochrous yellow. altitude of approximately 900 ft. a.s.l, in November 20: Both adults with two young Savannah Woodland, comprised mainly of noted. Water level 8 inches below the spill the Blue Gum, Eucalyptus leucoxylon. The way wall. dam wall is formed by an earth bank and November 23: Two adults; the young as it has been placed across a creekbed the were not seen. resultant shape of the dam is a long narrow December 1: Both adults were noted carry triangle with one small inlet on its northern ing material to a new nest site. Only one side formed by a second, smaller creek. The young bird seen. W.L. 12 inches below walL depth of the water at the deepest point is approximately 8 to 10 feet, and the appro December 12: One bird sitting on the priate levels below the spillway wall are second nest, leaving only when approached given. -

Grebe, Red-Necked

Grebes — Family Podicipedidae 101 Red-necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena Winter: One was at Sweetwater Reservoir (S12) 20 December 1969–2 January 1970 (AFN 24:538, 1970), one Uncommon as a winter visitor even in coastal was at the south end of San Diego Bay (V10) 14 March northern California, the Red-necked Grebe is casual 1977 (AB 31:372, 1977), and one was at Santee Lakes (P12) as far south as San Diego County, where there are 30 December 1984–6 January 1985 (D. and N. Kelly, AB three well-supported records. These are the south- 39:209, 1985). Other published reports from the 1950s ernmost for the species along the Pacific coast; the and 1960s are more likely of misidentified Horned Grebes Red-necked Grebe is unknown in Mexico. (Unitt 1984). Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis Grebe winters by the thousands. Though the grebe Though highly migratory, the Eared Grebe is also is still common on both fresh and salt water else- flightless for much of the year; its breast muscles where, the numbers are much smaller. As a breeding atrophy except when needed for migration. Breeding bird the Eared Grebe is rare and irregular in San birds use ponds and marshes with fresh to brackish Diego County, which lies near the southern tip of water, but nonbreeders concentrate in water that is the breeding range. hypersaline. In San Diego County, such conditions Winter: The salt works at the south end of San Diego Bay are found in south San Diego Bay, where the Eared are the center for the Eared Grebe in San Diego County. -

Compendium of Avian Ecology

Compendium of Avian Ecology ZOL 360 Brian M. Napoletano All images taken from the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framlst/infocenter.html Taxonomic information based on the A.O.U. Check List of North American Birds, 7th Edition, 1998. Ecological Information obtained from multiple sources, including The Sibley Guide to Birds, Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Nest and other images scanned from the ZOL 360 Coursepack. Neither the images nor the information herein be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior consent of the original copyright holders. Full Species Names Common Loon Wood Duck Gaviiformes Anseriformes Gaviidae Anatidae Gavia immer Anatinae Anatini Horned Grebe Aix sponsa Podicipediformes Mallard Podicipedidae Anseriformes Podiceps auritus Anatidae Double-crested Cormorant Anatinae Pelecaniformes Anatini Phalacrocoracidae Anas platyrhynchos Phalacrocorax auritus Blue-Winged Teal Anseriformes Tundra Swan Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Anatini Cygnini Anas discors Cygnus columbianus Canvasback Anseriformes Snow Goose Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Aythyini Anserini Aythya valisineria Chen caerulescens Common Goldeneye Canada Goose Anseriformes Anseriformes Anatidae Anserinae Anatinae Anserini Aythyini Branta canadensis Bucephala clangula Red-Breasted Merganser Caspian Tern Anseriformes Charadriiformes Anatidae Scolopaci Anatinae Laridae Aythyini Sterninae Mergus serrator Sterna caspia Hooded Merganser Anseriformes Black Tern Anatidae Charadriiformes Anatinae -

An Avian Quadrate from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(4):712-719, December 2000 © 2000 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology AN AVIAN QUADRATE FROM THE LATE CRETACEOUS LANCE FORMATION OF WYOMING ANDRZEJ ELZANOWSKll, GREGORY S. PAUV, and THOMAS A. STIDHAM3 'Institute of Zoology, University of Wroclaw, Ul. Sienkiewicza 21, 50335 Wroclaw, Poland; 23109 N. Calvert St., Baltimore, Maryland 21218 U.S.A.; 3Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 U.S.A. ABSTRACT-Based on an extensive survey of quadrate morphology in extant and fossil birds, a complete quadrate from the Maastrichtian Lance Formation has been assigned to a new genus of most probably odontognathous birds. The quadrate shares with that of the Odontognathae a rare configuration of the mandibular condyles and primitive avian traits, and with the Hesperomithidae a unique pterygoid articulation and a poorly defined (if any) division of the head. However, the quadrate differs from that of the Hesperomithidae by a hinge-like temporal articulation, a small size of the orbital process, a well-marked attachment for the medial (deep) layers of the protractor pterygoidei et quadrati muscle, and several other details. These differences, as well as the relatively small size of about 1.5-2.0 kg, suggest a feeding specialization different from that of Hesperomithidae. INTRODUCTION bination of its morphology, size, and both stratigraphic and geo- graphic occurrence effectively precludes its assignment to any The avian quadrate shows great taxonomic differences of a few fossil genera that are based on fragmentary material among the higher taxa of birds in the structure of its mandibular, without the quadrate. -

Great Crested Grebe Podiceps Cristatus in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu

120 Indian BIRDS VOL. 14 NO. 4 (PUBL. 23 OCTOBER 2018) Bristled Grassbird Chaetornis striata: A pair of Grassbirds was George, A., 2018. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S43199767. [Accessed seen on 24 February 2018, photographed [119] on 26 February, on 13 August 2018.] and seen on the subsequent day as well. This adds to the recent George, P. J., 2015. Chestnut-eared Bunting Emberiza fucata from Ezhumaanthuruthu, Kuttanad Wetlands, Kottayam District. Malabar Trogon 13 (1): 34–35. knowledge on its wintering status in Karnataka. Other records Harshith, J. V., 2016. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S33278635. are from Dakshin Kannada (Harshith 2016; Kamath 2016; [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Viswanathan 2017), Mysuru (Vijayalakshmi 2016), and Belgaum Kamath, R., 2016. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S33148312. [Accessed (Sant 2017). on 13 August 2018.] Lakshmi, V., 2015. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S21432671. [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Monnappa, B., 2012. Website URL: https://www.indianaturewatch.net/displayimage. php?id=317526. [Accessed on 14 August 2018.] Nair. A. 2018. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S43311515. [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Naoroji, R., 2006. Birds of prey of the Indian Subcontinent. Reprint ed. New Delhi: Om Books International. Pp. 1–692. Narasimhan, S. V., 2004. Feathered jewels of Coorg. 1st ed. Madikeri, India: Coorg Wildlife Society. Pp. 1–192. Orta, J., Boesman, P., Marks, J. S., Garcia, E. F. J., & Kirwan, G. M., 2018. Western Marsh- harrier (Circus aeruginosus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A., & de Juana, E., (eds.). -

Pied-Billed Grebe (Podilymbus Podiceps) Damon Mccormick

Pied-billed Grebe (Podilymbus podiceps) Damon McCormick Washington. 6/16/2008 © Jerry Jourdan (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) To early naturalists it was the “hell-diver” or limit of the species’ range, “it nests abundantly in every suitable place in the state, from the “water-witch”, and its idiosyncrasies tended to Ohio-Indiana line to Lake Superior.” inspire hyperbole: “These peculiar little spirits Subsequent surveys in the 20th Century of the water present a very radical departure however, recorded decidedly less than abundant from what the word ‘bird’ usually brings to densities in the NLP and UP, and MBBA I mind” (Rockwell 1910). Occupying its own documented a significantly higher percentage of genus within the seven-member North breeding Pied-billed Grebes in the SLP, American Podicipedidae family, the Pied-billed particularly in southwestern counties (Storer Grebe, while by no means singularly non-avian, 1991). was not mischaracterized by its antiquated appellations. With a pattern of nocturnal Breeding Biology migration and a propensity to dive rather than Pied-billed Grebes tend to occupy fresh to fly in response to threats, the species is almost moderately brackish waterbodies greater than exclusively encountered upon the marshes and 0.2 ha, marked by dense stands of emergent ponds that constitute its summer home vegetation and ample stretches of open water (Wetmore 1924, Muller and Storer 1999). A (Muller and Storer 1999). Their cuckoo-like breeding adult, diminutive and drably adorned song – “far-carrying, vibrant, throaty barks” – in brown and gray, nonetheless demonstrates a can be vocalized by both sexes, and is strident territoriality within its wetland turf, associated with courtship and territorial responding aggressively to both intra- and inter- delineation (Deusing 1939, Muller and Storer specific interlopers (Glover 1953, McAllister 1999, Sibley 2000).