(82) FIELD NOTES on the LITTLE GREBE. the Following Observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps R. Ruficollis) Were Made at Fetch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

Little Grebe

A CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SAADANI. Little Grebe Black-chested Snake Eagle Redshank Little Swift White Pelican Bateleur Terek Sandpiper Eurasian Swift Pink-backed Pelican African Goshawk Sanderling White-rumped Swift Long-tailed Cormorant Steppe Eagle Curlew Sandpiper Palm Swift Darter Tawny Eagle Little Stint Bohm's Spinetail Little Bittern Augur Buzzard Black-tailed Godwit Speckled Mousebird Grey Heron Lizard Buzzard Ruff Blue-naped Mousebird Goliath Heron Pale Chanting Goshawk Turnstone Narina Trogon Cattle Egret Martial Eagle Black-winged Stilt Pied Kingfisher Green-backed Heron Crowned Eagle Avocet Malachite Kingfisher Great White Egret Fish Eagle Water Thicknee Brown-hooded Kingfisher Black Heron Black Kite Temminck's Courser Striped Kingfisher Little Egret Osprey Lesser Black-backed Gull Chestnut-bellied Kingfisher Yellow-billed Egret African Hobby White-winged Black Tern Mangrove Kingfisher Night Heron Hobby Gull-billed Tern Pygmy Kingfisher Hamerkop Kestrel Little Tern White-throated Bee-eater Open-billed Stork Red-necked Spurfowl Lesser Crested Tern Eurasian Bee-eater Woolly-necked Stork Crested Francolin Swift Tern Swallow-tailed Bee-eater Yellow-billed Stork Crested Guineafowl Caspian Tern Northern Carmine Bee-eater Hadada Ibis Helmeted Guineafowl Common Tern Blue-cheeked Bee-eater Sacred Ibis Black Crake Ring-necked Dove Little Bee-eater African Spoonbill Black-bellied Bustard Red-eyed Dove Madagascar Bee-eater Lesser Flamingo Jacana Emerald-spotted Wood Dove Lilac-breasted Roller Greater Flamingo Ringed Plover Tambourine -

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and Area

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and area Reproduced with kind permission of Etienne Marais of Indicator Birding Visit www.birding.co.za for more info and details of birding tours and events Endemic birds KEY: SA = South African Endemic, SnA = Endemic to Southern Africa, NE = Near endemic (Birders endemic) to the Southern African Region. RAR = Rarity Status KEY: cr = common resident; nr = nomadic breeding resident; unc = uncommon resident; rr = rare; ? = status uncertain; s = summer visitor; w = winter visitor r Endemicity Numbe Sasol English Status All Scientific p 30 Little Grebe cr Tachybaptus ruficollis p 30 Black-necked Grebe nr Podiceps nigricollis p 56 African Darter cr Anhinga rufa p 56 Reed Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax africanus p 56 White-breasted Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax lucidus p 58 Great White Pelican nr Pelecanus onocrotalus p 58 Pink-backed Pelican ? Pelecanus rufescens p 60 Grey Heron cr Ardea cinerea p 60 Black-headed Heron cr Ardea melanocephala p 60 Goliath Heron cr Ardea goliath p 60 Purple Heron uncr Ardea purpurea p 62 Little Egret uncr Egretta garzetta p 62 Yellow-billed Egret uncr Egretta intermedia p 62 Great Egret cr Egretta alba p 62 Cattle Egret cr Bubulcus ibis p 62 Squacco Heron cr Ardeola ralloides p 64 Black Heron uncs Egretta ardesiaca p 64 Rufous-bellied Heron ? Ardeola rufiventris RA p 64 White-backed Night-Heron rr Gorsachius leuconotus RA p 64 Slaty Egret ? Egretta vinaceigula p 66 Green-backed Heron cr Butorides striata p 66 Black-crowned Night-Heron uncr Nycticorax nycticorax p -

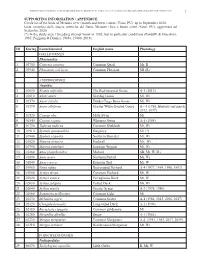

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Aberrant Plumages in Grebes Podicipedidae

André Konter Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae in grebes plumages Aberrant Ferrantia André Konter Travaux scientifiques du Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg www.mnhn.lu 72 2015 Ferrantia 72 2015 2015 72 Ferrantia est une revue publiée à intervalles non réguliers par le Musée national d’histoire naturelle à Luxembourg. Elle fait suite, avec la même tomaison, aux TRAVAUX SCIENTIFIQUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE DE LUXEMBOURG parus entre 1981 et 1999. Comité de rédaction: Eric Buttini Guy Colling Edmée Engel Thierry Helminger Mise en page: Romain Bei Design: Thierry Helminger Prix du volume: 15 € Rédaction: Échange: Musée national d’histoire naturelle Exchange MNHN Rédaction Ferrantia c/o Musée national d’histoire naturelle 25, rue Münster 25, rue Münster L-2160 Luxembourg L-2160 Luxembourg Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Fax +352 46 38 48 Fax +352 46 38 48 Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/ Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/exchange email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Page de couverture: 1. Great Crested Grebe, Lake IJssel, Netherlands, April 2002 (PCRcr200303303), photo A. Konter. 2. Red-necked Grebe, Tunkwa Lake, British Columbia, Canada, 2006 (PGRho200501022), photo K. T. Karlson. 3. Great Crested Grebe, Rotterdam-IJsselmonde, Netherlands, August 2006 (PCRcr200602012), photo C. van Rijswik. Citation: André Konter 2015. - Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae - An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide. Ferrantia 72, Musée national d’histoire naturelle, Luxembourg, 206 p. -

Pied-Billed Grebe Breeding in Argyll, Pages 18-21 Recent Bird Sightings, Pages 10-13 Treshnish Isles Auk Ringing Group, Pages 227-29

The Eider is the Quarterly Newsletter of the Argyll Bird Club (http://www.argyllbirdclub.org) - Scottish Charity No. SC 008782 - Eider September 2017 (no. 121) September 2017 Number 121 Rose-coloured Starling at Laphroaig, Islay on 24 June ©Garry Turnbull Pied-billed Grebe breeding in Argyll, pages 18-21 Recent bird sightings, pages 10-13 Treshnish Isles Auk Ringing Group, pages 227-29 To receive the electronic version of The Eider in colour, ABC members should send their e-mail address Bob Furness (contact details on back page). Past issues (since June 2002) can be downloaded from the club’s website. 2 - Eider September 2017 (no. 121) Editor: Steve Petty, Cluaran Cottage, Ardentinny, Dunoon, Argyll PA23 8TR Phone 01369 810024—E-mail [email protected] Club News Inside this issue Club news Pages 3-5 FIELD TRIPS 2017 Papers for the AGM Pages 6-9 If there is a chance that adverse weather might lead to the cancellation of a field trip, please Recent bird sightings, May Pages 10-13 check the club’s website or contact the organiser to June the night before or prior to setting off. Pied-billed Grebe breeding Pages 14-15 in Argyll Saturday 16 September to Tuesday 19 Trip to Lesvos, April 2017 Pages 15-19 September. Tiree. Led by David Jardine (phone 01546 510200. e-mail Crow observation Pages 20-21 [email protected] ). A provisional booking has been made for some accommodation on Tiree Belated news item! Page 21 from Saturday 16 September to Tuesday 19 Sep- tember. Ferry departs Oban at 07.15hrs on Sat- ABC field trip to Loch Lo- Pages 22-23 urday and returns to Oban 22.40hrs on the Tues- mond day. -

The Water Birds of Mavoor Wetland, Kerala, South India

World Journal of Zoology 7 (2): 98-101, 2012 ISSN 1817-3098 © IDOSI Publications, 2012 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wjz.2012.7.2.6216 The Water Birds of Mavoor Wetland, Kerala, South India 12K.M. Aarif and Muhammad Basheer 1Kallingal House, Athanikunnu, Mampad College Po, Malapuram dt, Kerala, South India 2Palishakottu purayil, Elettil Po, Koduvally, Calicut, Kerala, South India Abstract: Bird Community of Mavoor Wetlands in Calicut District, Kerala State was studied during Sept 2009 to Aug 2010. The methodology followed was mainly observations using binocular. A total of 57 species of birds, belonging to 16 families were recorded from the area during the period. Among them 17 species are migrants. Highest number of birds was recorded in the month of January and the lowest was observed June. Little Egret, Little Cormorant, Purple Moorhen, Purple Heron, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Indian Pond-Heron, Little Grebe, Lesser Whistling-Duck, River Tern, Whiskered Tern, Garganey etc. were the most abundant resident and migrant species found in the Mavoor wetlands. Key words: Brids Mavoor Wetland Conservation Problem INTRODUCTION season the water level raises up to 2 to 4 meters. Studies on the avian fauna of Mavoor wetland are very few, Wetlands are extremely important areas throughout except the regular Asian Water fowl Census since past the world for wildlife protection, recreation, sediment five years and a PhD work on the diving behaviour of control, flood prevention [1]. Wetlands are important Cormorants and Darter [6]. bird habitats and birds use them for feeding, roosting, Systematic list of the birds of this region is lacking. -

Body Weights of Newly Hatched Anatidae.--As Early As 1928 (E

1965Oct. ] GeneralNotes 645 following day, Boulva found the bird again on the same territory, identified it posi- tively as a Le Conte's Sparrow (Passerherbuluscaudacutus), and photographed it with a 400 mm telephoto lens. On 23 July the second writer, after long observation, identified a Le Conte's Sparrow on the same territory. On 27 July Mr. Franqois Hamel, from "le Club des Ornithologues de Quebec," with Browne, had occasionto study the bird and its song; he too was convinced that the bird was a Le Conte's Sparrow. On 28 July both writers sighted two Le Conte's Sparrows together, captured one of the birds, and banded it (U.S.F.&W.S. band no. 52-39003, size 1). On 31 July, Mr. Raymond Cayouette, Curator of Birds at the Quebec Zoological Garden and President of "le Club des Ornithologuesde Quebec," with the Reverend Robert Plante of the same club, botb accompaniedby the first writer, were able to study the sparrow and were satisfied with the identification. On 11 August Browne caught a young Le Conte's Sparrow incapable of flight and banded it (band no. 103-42113, size 0), while two adults, one seen to be banded, were flying about. The young bird was well-feathered but had some down adhering to the plumage. The primaries were full grown except for the two outermost (pri- maries 8 and 9), which were short and still sheathed at the base. The tail feathers were well grown and pointed. The plumage was typical of the juvenal plumage of the species(see T. -

A PODICEPS PRIMER by Matthew L. Pelikan Wintertime Grebes Lack

A PODICEPS PRIMER by Matthew L. Pelikan Wintertime grebes lack charisma. They swim like logs and fly like windup toys. Their spectacular courtship choreography is months and hundreds of miles away. In dull winter plumage, even an Eared Grebe has a sort of check-it-off, go-warm-up-in-the-car quality. The marine habits of wintering grebes make close observation difficult. But bizarre life histories and intriguing behavior make Podiceps grebes appealing —once you get acquainted. Homed (in Europe known as Slavonia), Eared (i.e.. Black-necked), and Red-necked grebes share similar characteristics. Stubby wings, dense bodies, and rear-mounted feet make them more deft in water than on land or in flight. They breed mostly on shallow, weedy ponds well to the north. Sometimes isolated, sometimes colonial, their floating nests are attached to vegetation. During fall migration, grebes group at staging areas, then disperse to winter on lakes and sea coasts. Their opportunistic diet comprises invertebrates and fish, the latter more important in winter. All these grebes display considerable variability in appearance and behavior. But each species shapes this basic pattern into a unique form. The species of most interest to Massachusetts birders is the Eared Grebe (Podiceps nigricollis). Many readers no doubt enjoyed the very active Eared Grebe on Cape Ann during Febmary 1994. Birders who missed the show should not despair: this species is a rare but nearly annual visitor with about thirty state records (Veit and Petersen 1993). Reasonably, but without explanation, Harrison (1985) ascribes east-coast Eared Grebes to the North American subspecies (one of four worldwide), P. -

BREEDING of the LITTLE GREBE by G

THE S.A. ORNITHOLOGIST 109 BREEDING OF THE LITTLE GREBE By G. CLARKE. The following is a brief synopsis of events, continuously an agitated 'clip' or 'jip', a not altogether complete, of the breeding of single note. The nest was found to be a pair of Little Grebe (Podiceps nouaehol placed between a few sapling eucalypts 2 landiae) on the main dam at the Para Wirra to 3 feet in height, standing in the water, National Park, 20 miles NNE of Adelaide and was composed mainly of rush stems in the Mt. Lofty Ranges. (funcus) 'anchored' between the. saplings and The dam occupies an area of some two resembling a pile of. debris. The nest con and a half acres, and is situated at an tained three eggs, stained an ochrous yellow. altitude of approximately 900 ft. a.s.l, in November 20: Both adults with two young Savannah Woodland, comprised mainly of noted. Water level 8 inches below the spill the Blue Gum, Eucalyptus leucoxylon. The way wall. dam wall is formed by an earth bank and November 23: Two adults; the young as it has been placed across a creekbed the were not seen. resultant shape of the dam is a long narrow December 1: Both adults were noted carry triangle with one small inlet on its northern ing material to a new nest site. Only one side formed by a second, smaller creek. The young bird seen. W.L. 12 inches below walL depth of the water at the deepest point is approximately 8 to 10 feet, and the appro December 12: One bird sitting on the priate levels below the spillway wall are second nest, leaving only when approached given. -

Grebe, Red-Necked

Grebes — Family Podicipedidae 101 Red-necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena Winter: One was at Sweetwater Reservoir (S12) 20 December 1969–2 January 1970 (AFN 24:538, 1970), one Uncommon as a winter visitor even in coastal was at the south end of San Diego Bay (V10) 14 March northern California, the Red-necked Grebe is casual 1977 (AB 31:372, 1977), and one was at Santee Lakes (P12) as far south as San Diego County, where there are 30 December 1984–6 January 1985 (D. and N. Kelly, AB three well-supported records. These are the south- 39:209, 1985). Other published reports from the 1950s ernmost for the species along the Pacific coast; the and 1960s are more likely of misidentified Horned Grebes Red-necked Grebe is unknown in Mexico. (Unitt 1984). Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis Grebe winters by the thousands. Though the grebe Though highly migratory, the Eared Grebe is also is still common on both fresh and salt water else- flightless for much of the year; its breast muscles where, the numbers are much smaller. As a breeding atrophy except when needed for migration. Breeding bird the Eared Grebe is rare and irregular in San birds use ponds and marshes with fresh to brackish Diego County, which lies near the southern tip of water, but nonbreeders concentrate in water that is the breeding range. hypersaline. In San Diego County, such conditions Winter: The salt works at the south end of San Diego Bay are found in south San Diego Bay, where the Eared are the center for the Eared Grebe in San Diego County. -

An Avian Quadrate from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(4):712-719, December 2000 © 2000 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology AN AVIAN QUADRATE FROM THE LATE CRETACEOUS LANCE FORMATION OF WYOMING ANDRZEJ ELZANOWSKll, GREGORY S. PAUV, and THOMAS A. STIDHAM3 'Institute of Zoology, University of Wroclaw, Ul. Sienkiewicza 21, 50335 Wroclaw, Poland; 23109 N. Calvert St., Baltimore, Maryland 21218 U.S.A.; 3Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 U.S.A. ABSTRACT-Based on an extensive survey of quadrate morphology in extant and fossil birds, a complete quadrate from the Maastrichtian Lance Formation has been assigned to a new genus of most probably odontognathous birds. The quadrate shares with that of the Odontognathae a rare configuration of the mandibular condyles and primitive avian traits, and with the Hesperomithidae a unique pterygoid articulation and a poorly defined (if any) division of the head. However, the quadrate differs from that of the Hesperomithidae by a hinge-like temporal articulation, a small size of the orbital process, a well-marked attachment for the medial (deep) layers of the protractor pterygoidei et quadrati muscle, and several other details. These differences, as well as the relatively small size of about 1.5-2.0 kg, suggest a feeding specialization different from that of Hesperomithidae. INTRODUCTION bination of its morphology, size, and both stratigraphic and geo- graphic occurrence effectively precludes its assignment to any The avian quadrate shows great taxonomic differences of a few fossil genera that are based on fragmentary material among the higher taxa of birds in the structure of its mandibular, without the quadrate.